SHOULDER JOINT

Table of Contents

Introduction of Shoulder Joint

- The glenohumeral joint is structurally a ball-and-socket joint and functionally is considered a diarthrodial, multiaxial, joint.

- The glenohumeral articulation involves the humeral head with the glenoid cavity of the scapula, and it represents the major articulation of the shoulder girdle.

- The latter also includes minor articulations of the sternoclavicular (SC), acromioclavicular (AC), and scapulothoracic joints.

- The glenohumeral joint is the most mobile joint of the human body.

- The static and dynamic stabilizing structures allow for extreme degrees of motion in multiple planes of the body that predispose the joint to instability events.

Structure and Function of Shoulder Joint:

- The glenohumeral joint is a ball and socket joint that includes a complex, dynamic, articulation between the glenoid of the scapula and the proximal humerus.

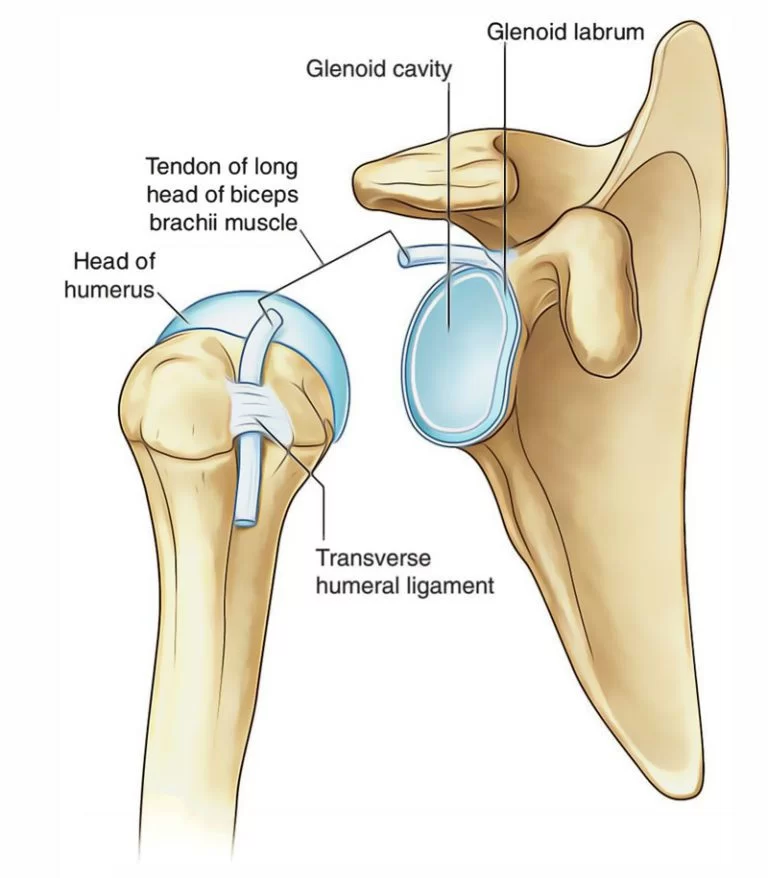

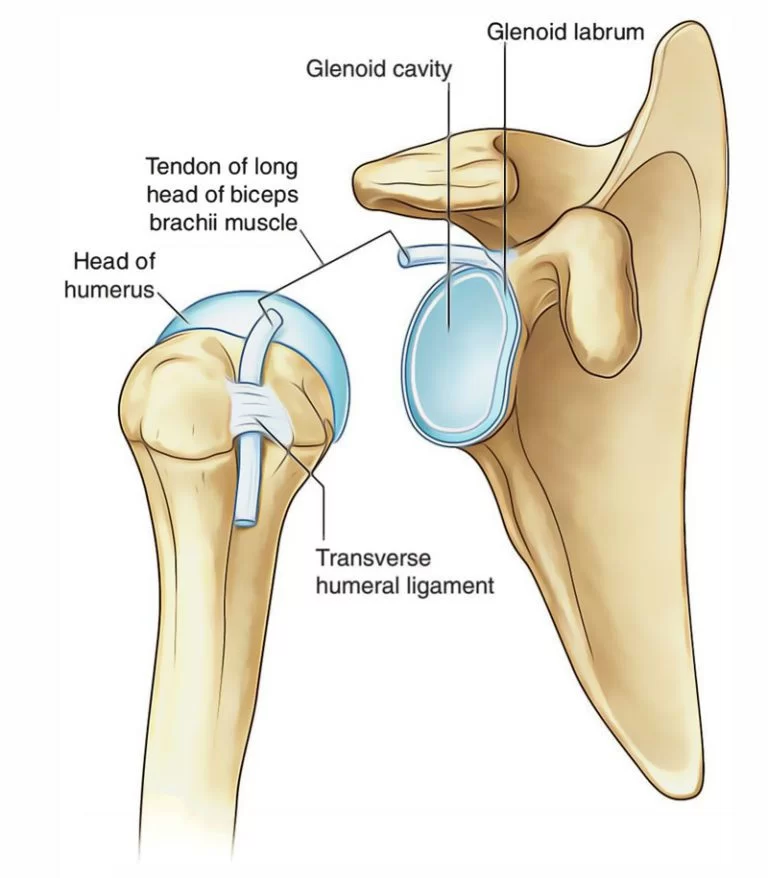

- Specifically, it is the head of the humerus that contacts the glenoid cavity (or fossa) of the scapula.

- The articulating surfaces of both are lined by articular cartilage.

- The glenoid cavity is a shallow osseous element that is structurally deepened by a fibrocartilagenous rim, the glenoid labrum, that spans the osseous periphery of the vault.

- The labrum is continuous with the tendon of the biceps brachii at its superior aspect.

- Due to the loose joint capsule, and the relative size of the humeral head compared to the shallow glenoid fossa (4:1 ratio in surface area), it is one of the most mobile joints in the human body.

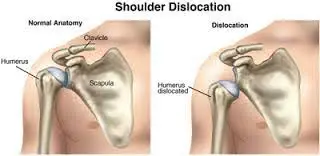

- This increased mobility contributes to it being the most commonly dislocated joint.

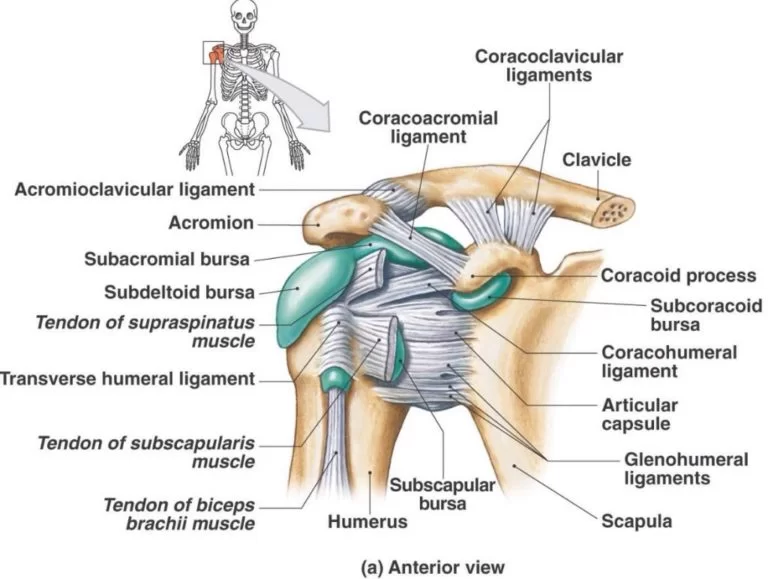

- The glenohumeral joint is enclosed by a joint capsule that encapsulates the structures of the joint in a fibrous sheath.

- Structurally the joint capsule wraps around the anatomic neck of the humerus to the rim of the glenoid fossa.

- While the joint capsule itself is a contiguous supportive structure surrounding the articulating elements, the capsulolabral complexes include important characteristic thickened bands that constitute the glenohumeral ligaments.

- First described in 1829, the glenohumeral ligaments do not act as traditional ligaments that carry a pure tensile force along their length, but rather, the glenohumeral ligaments become taut at varying positions of abduction and humeral rotation.

- A synovial membrane forms the lining of the inner surface of the joint capsule.

- This membrane produces synovial fluid to reduce friction between the articular surfaces.

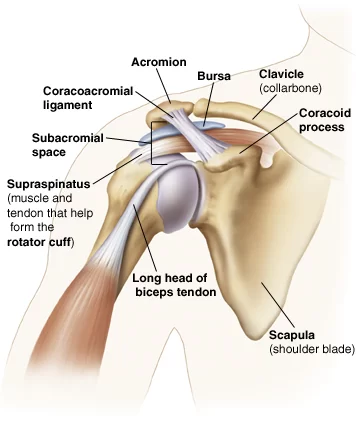

- In addition to the synovial fluid reducing friction within the joint, there are multiple synovial bursae present as well.

- These bursae functionally act as a cushion between joint structures, such as tendons.

- The most clinically significant are the subacromial and subscapular bursae.

There are numerous including:

- Subacromial/subdeltoid bursa – which lays between the deltoid muscle and joint capsule in the superolateral aspect of the joint.

- It is superficial to the supraspinatus tendon.

- This bursa reduces friction underneath the deltoid muscle allowing increased range of motion.

- This bursa, excluding anatomic variants, does not usually communicate with the shoulder joint itself.

- Subcoracoid bursa – located between the coracoid process and the capsule.

- Coracobrachial bursa – is between the tendon of the coracobrachialis muscle and the subscapularis muscle.

- Subscapular bursa – is located between the tendon of the subscapularis muscle and the capsule.

- It functions to reduce frictional damage to the subscapularis muscle during movement of the glenohumeral joint, particularly during internal rotation.

- Static stabilizing structures include the osseous articular anatomy and joint congruity, the glenoid labrum, the glenohumeral ligaments, the joint capsule, and negative intraarticular pressure:

- Glenohumeral ligaments- Composed of a superior, middle, and inferior ligament, these three ligaments combine to form the glenohumeral joint capsule connecting the glenoid fossa to the humerus.

- Due to their location, they protect the shoulder and prevent it from dislocating anteriorly — this group of ligaments functions as the primary stabilizers of the joint.

- Coracoclavicular ligament – This ligament is composed of the conoid and trapezoid ligaments and spans from the coracoid process to the clavicle.

- It functions to maintain the position of the clavicle in conjunction with the acromioclavicular ligament.

- Strong forces can rupture these ligaments during acromioclavicular joint injuries.

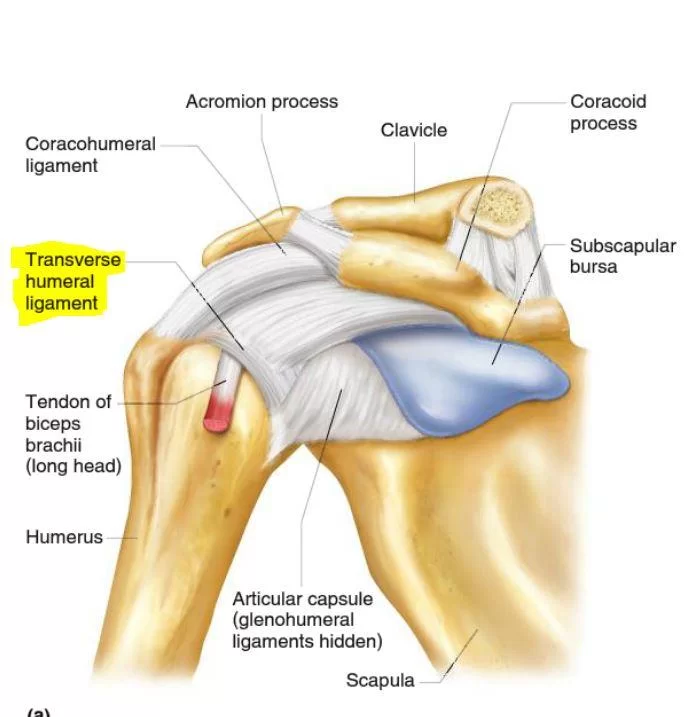

- Coracohumeral ligament – This ligament supports the superior aspect of the joint capsule.

- It originates on the coracoid process and attaches to the greater tubercle of the humerus.

- Soft tissue pulley system, Long head of the biceps tendon (LHBT) The coracohumeral ligament (CHL) The superior glenohumeral ligament (SGHL)

- The subscapularis has superficial and deep fibers that envelope the groove, creating the “roof” and “floor,” respectively. -These fibers also coalesce with those from the supraspinatus and SGHL/CHL complex. -These structures attach intimately at the lesser tuberosity to create the proximal and medial aspect of the pulley system, with soft tissue extensions serving to further envelope the LHBT in the bicipital groove. -The CHL is a dense fibrous structure connecting the base of the coracoid process to the greater and lesser tuberosities. -At its origin, the ligament is thin and broad, measuring about 2 cm in diameter at the base of the coracoid. Laterally, the CHL separates into 2 distinct bands that envelope the LHBT at the proximal extent of the bicipital groove. -Once the LHBT exits the groove, it takes a 30- to 40-degree turn as it heads toward the supraglenoid tubercle and glenoid labrum. -Thus, the proximal soft tissue elements of the groove are especially critical for the overall stability of the entire complex. -In addition to the CHL, the SGHL reinforces the complex at this proximal exit point. -The SGHL travels from the superior labrum to the lesser tuberosity, becoming confluent with the soft tissue pulley as it takes on a U-shaped configuration

- Transverse humeral ligament – no longer considered to have a role in shoulder girdle or LHBT stability. Overall existence as a distinct, anatomic structure is debated

- Dynamic restraints to shoulder motion include the LHBT, rotator cuff muscle, rotator interval, and periscapular muscles.

Spaces in shoulder joint:

Significant joint spaces are:

- The normal glenohumeral space is 4–5 mm.

- Supraspinatus outlet view X-ray, showing subacromial space measurement.

- The normal subacromial space in shoulder radiographs is 9–10 mm;

- This space is significantly greater in men, with a slight reduction with age.

- In middle age, a subacromial space less than 6 mm is pathological, and may indicate a rupture of the tendon of the supraspinatus muscle.

- The axillary space is an anatomic space between the associated muscles of the shoulder.

- This space transmits the subscapular artery and axillary nerve.

Embryology of Shoulder Joint:

- The development of the skeletal shoulder consists of both forms of ossification processes.

- The clavicle undergoes intramembranous ossification which is the direct laying down of bone into the mesenchyme.

- The rest of the bony structures of the shoulder form by endochondral ossification.

- The mesoderm germ layer forms nearly all of the connective tissues of the musculoskeletal system, including the glenohumeral joint.

- Musculoskeletal and limb abnormalities, due to both environmental and genetic contributions, are one of the largest groups of congenital abnormalities.

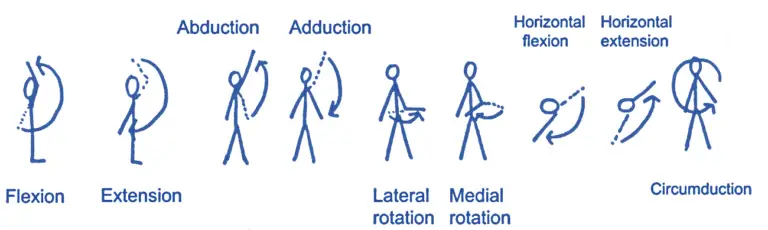

- The glenohumeral joint possesses the capability of allowing an extreme range of motion degrees in multiple planes.

- Flexion – Defined as bringing the upper limb anterior in the sagittal plane.

- The normal range of motion is considered to be 180 degrees.

- The main flexors of the shoulder are the anterior deltoid, coracobrachialis, and pectoralis major.

- Biceps brachii also weakly assists in this action.

- Extension—Defined as bringing the upper limb posterior in a sagittal plane.

- The normal range of motion is considered to be 45-60 degrees.

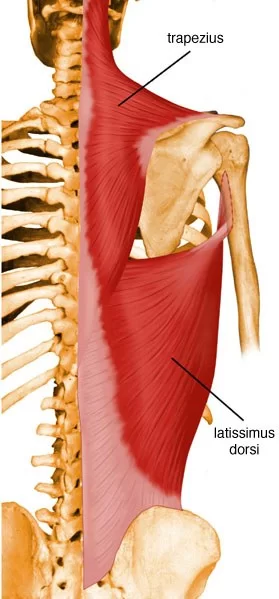

- The main extensors of the shoulder are the posterior deltoid, latissimus dorsi, and teres major.

- Internal rotation—Defined as rotation toward the midline along a vertical axis.

- The normal range of motion is considered to be 70-90 degrees.

- The internal rotation muscles are subscapularis, pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, teres major, and the anterior aspect of the deltoid.

- External rotation – Defined as rotation away from the midline along a vertical axis.

- The normal range of motion is considered to be 90 degrees.

- Primarily infraspinatus and teres minor are responsible for the motion.

- Adduction – Defined as bringing the upper limb towards the midline in the coronal plane.

- Pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, and teres major are the muscles primarily responsible for shoulder adduction.

- Abduction – Defined as bringing the upper limb away from the midline in the coronal plane.

- The normal range of motion is considered to be 150 degrees.

- Due to the ability to differentiate several pathologies by the range of motion of the glenohumeral joint in this plane of motion, it is essential to understand how different muscles contribute to this action.

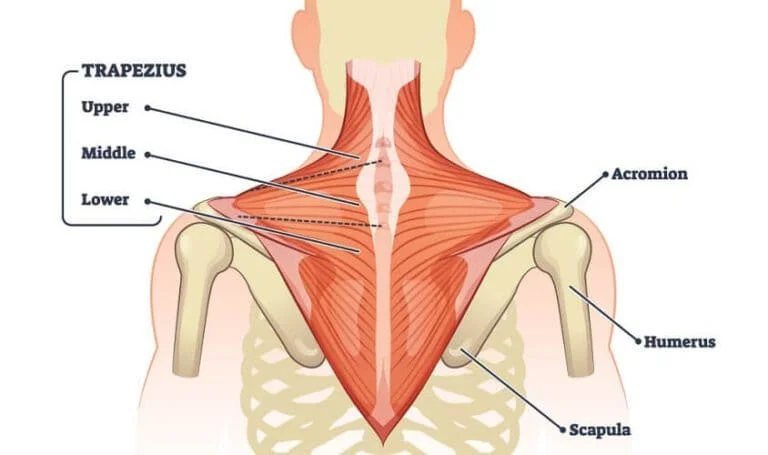

- I. The supraspinatus is responsible for the first 0 to 15 degrees of abduction II. The middle fibers of the deltoid are responsible for approximately 15-90 degrees of abduction following III. Scapular rotation due to the actions of the trapezius and serratus anterior allows for abduction beyond 90 degrees

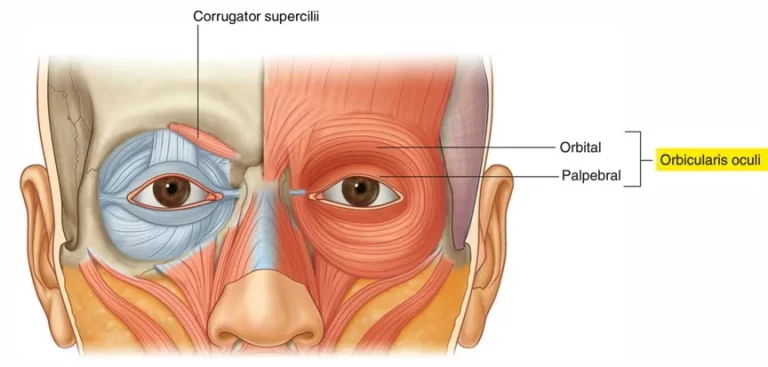

Muscles of the shoulder joint:

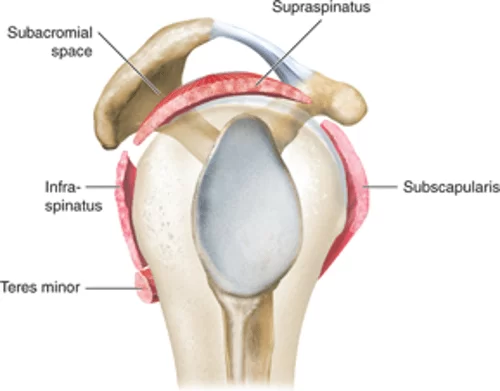

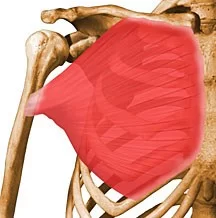

- The four muscles that constitute the rotator cuff are the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis, and teres minor.

- The primary biomechanical role of the rotator cuff is stabilizing the glenohumeral joint by compressing the humeral head against the glenoid.

- The rotator cuff muscles provide dynamic restraint as normal physiologic function directly contributes to glenohumeral stability.

- In addition to the rotator cuff, the LHBT has a controversial contribution and overall role in glenohumeral joint stability.

- The current consensus agreement is that the stabilizing role of the LHBT in regard to the glenohumeral joint becomes more important and/or relevant in the setting of rotator cuff dysfunction.

- The subscapularis muscle aids in the internal rotation of the shoulder.

- The long head of biceps brachii courses through the bicipital groove on the humerus to insert on the superior aspect of the glenoid.

Mobility and Stability of Shoulder Joint:

- The shoulder joint is one of the most mobile in the body, at the expense of stability. Here, we shall consider the factors that permit movement and those that contribute towards joint structure.

Factors that contribute to mobility:

- Type of joint – ball and socket joint.

- Bony surfaces – shallow glenoid cavity and large humeral head – there is a 1:4 disproportion in surfaces.

- A commonly used analogy is the golf ball and tee. Inherent laxity of the joint capsule.

Factors that contribute to the stability of Shoulder Joint:

- Rotator cuff muscles – surround the shoulder joint, attaching to the tuberosities of the humerus, whilst also fusing with the joint capsule.

- The resting tone of these muscles acts to compress the humeral head into the glenoid cavity.

- Glenoid labrum – a fibrocartilaginous ridge surrounding the glenoid cavity.

- It deepens the cavity and creates a seal with the head of the humerus, reducing the risk of dislocation.

- Ligaments – act to reinforce the joint capsule, and form the coracoacromial arch.

- Biceps tendon – it acts as a minor humeral head depressor, thereby contributing to stability.

Neurovasculature:

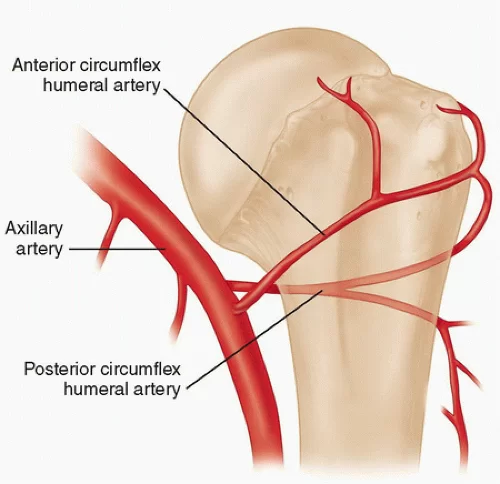

- The shoulder joint is supplied by the anterior and posterior circumflex humeral arteries, which are both branches of the axillary artery.

- Branches of the suprascapular artery, a branch of the thyrocervical trunk, also contribute.

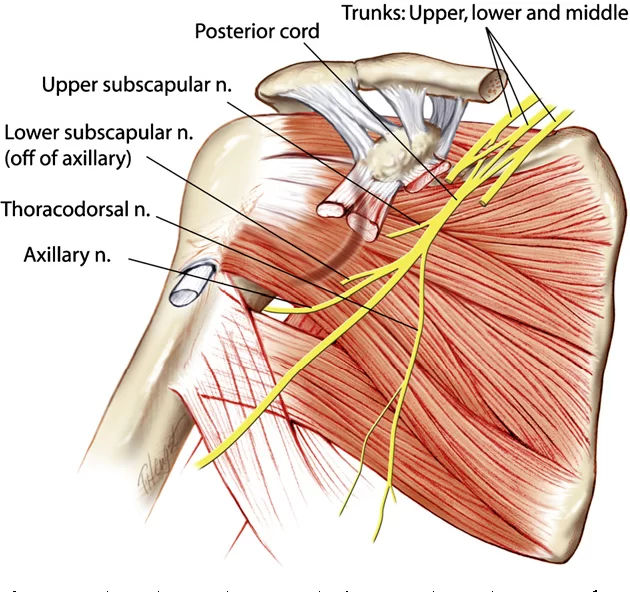

- Innervation is provided by the axillary, suprascapular, and lateral pectoral nerves

MUSCLES OF SHOULDER JOINT MOTION:

Flexion

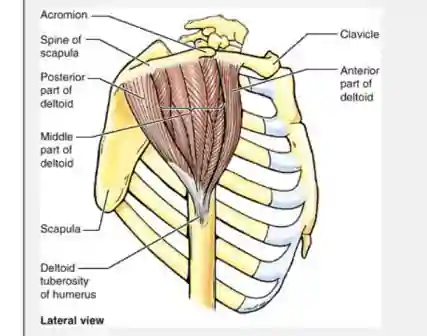

Deltoid [ant.]

- origin: anterior border and upper surface of the lateral third of the clavicle, acromion, spine of the scapula

- Insertion: deltoid tuberosity of humerus

- Arterial supply: thoracoacromial artery, anterior and posterior humeral circumflex artery

- innervation: Axillary nerve

- Actions: shoulder abduction, flexion and extension

- Daily uses: Lifting

- Stretches: Posterior shoulder stretch

- Strengthening exercises: Lateral raise, Front raise

- Coracobrachialis, biceps brachii (Accessory muscles)

Extension

Deltoid [post.]

- Origin: Lateral third of the clavicle, acromion, and spine of the scapula

- Insertion: Deltoid tuberosity of humerus

- Action: Anterior part: flexes and medially rotates arm

- abducts arm

- Posterior part: extends and laterally rotates arm

- Innervation: Axillary nerve (C5 and C6)

- Arterial Supply: Deltoid branch of thoracoacromial artery

- Teres major, latissimus dorsi, long head of biceps brachii (Accessory muscles)

Abduction

Deltoid (Prime mover)

Supraspinatus (Accessory muscles)

Adduction

Pectoralis Major [Prime movers]

- Origin: Clavicular head: anterior surface of the medial half of clavicle; – Sternocostal head: anterior surface of sternum, superior six costal cartilages, and aponeurosis of external oblique muscle

- Insertion: Lateral lip of intertubercular groove of humerus

- Action: Adducts and medially rotates humerus; draws scapula anteriorly and inferiorly; – Acting alone: clavicular head flexes humerus and sternocostal head extends it

- Innervation: Lateral and medial pectoral nerves; clavicular head (C5 and C6, sternocostal head (C7, C8, and T1)

- Arterial Supply: pectoral branch of the thoracoacromial trunk

- Daily uses: Using roll-on deodorant.

- Strengthening exercises: Pec fly using a resistance band. Chest Press using a resistance band.

- Stretches: Chest stretch, Chest stretch with a partner.

Lattismus dorsi [prime mover]

- Origin: Spinous processes of inferior 6 thoracic vertebrae, thoracolumbar fascia, iliac crest, and inferior 3 or 4 ribs

- Insertion: Floor of intertubercular groove of humerus

- Action: Extends, adducts, and medially rotates humerus; raises body toward arms during climbing

- Innervation: Thoracodorsal nerve (C6, C7, and C8)

- Arterial Supply: Thoracodorsal artery

- Daily uses: Pushing on the arms of a chair when standing up.

- Strengthening exercises: Lat. Pull down using a resistance band.

- Stretches: Latissimus dorsi stretch I. Latissimus dorsi stretch II.

- Teres major, long head of triceps brachii (Accessory muscles)

Medial Rotation

Subscapularis (Prime mover)

- Origin: Subscapular fossa of scapula

- Insertion: Lesser tuberosity of humerus

- Action: Medially rotates the arm and adducts it; helps to hold humeral head in the glenoid cavity of scapula

- Innervation: Upper and lower subscapular nerves (C5, C6 and C7

- Arterial Supply: Subscapular artery

- Strengthening exercises: similar to those of the latissimus dorsi and teres major, including pull-downs, rope climbs.

- Stretching: Externally rotate the shoulder and raise the arm up at the side (abduct).

- Pectoralis major, deltoid, latissimus dorsi, teres major (Accessory muscles)

Lateral Rotation

Infraspinatus (Prime mover)

- Origin: infraspinous fossa of scapula

- Insertion: Middle facet on greater tuberosity of humerus

- Action: Laterally rotate arm; helps to hold humeral head in the glenoid cavity of scapula

- Innervation: Suprascapular nerve (C5 and C6)

- Arterial Supply: Suprascapular and circumflex scapular arteries

- Daily uses: Brushing hair.

- Strengthening exercises: Lateral raise, Shoulder external (lateral) rotation.

- Stretches: Internal rotation stretch. – Posterior shoulder stretch.

- Teres major, deltoid (Accessory muscles)

Teres major

Origin: Dorsal surface of the inferior angle of the scapula

Insertion: Medial lip of intertubercular groove of humerus

Action: Adducts and medially rotates arm

Innervation: Lower subscapular nerve (C6 and C7)

Arterial Supply: Subscapular and circumflex scapular arteries

Daily uses: Tuck the back of your shirt into your trousers.

strengthening exercises: Shoulder internal rotation.

stretches External rotation stretch.

Rotator Cuff

Supraspinatus

origin : Supraspinous fossa of scapula

Insertion: Superior facet on greater tuberosity of humerus

Action: Initiates and assists deltoid in abduction of arm and acts with other rotator cuff muscles

Innervation: Suprascapular nerve (C4, C5 and C6)

Arterial Supply: Suprascapular artery

Daily uses: Holding shopping bags away from the body.

strengthening exercises: Lateral raise.

Shoulder external rotation.

stretches Supraspinatus stretch.

Posterior shoulder stretch.

Infraspinatus

Origin: Infraspinous fossa of scapula

Insertion: Middle facet on greater tuberosity of humerus

Action: Laterally rotate arm; helps to hold humeral head in the glenoid cavity of scapula

Innervation: Suprascapular nerve (C5 and C6)

Arterial Supply: Suprascapular and circumflex scapular arteries

Daily uses: Brushing hair.

Strengthening exercises: Lateral raise.

Shoulder external (lateral) rotation.

stretches Internal rotation stretch.

Posterior shoulder stretch.

Teres Minor

Origin: Superior part of lateral border of scapula

Insertion: Inferior facet on greater tuberosity of humerus

Action: Laterally rotate arm; helps to hold humeral head in the glenoid cavity of scapula

Innervation: Axillary nerve (C5 and C6)

Arterial Supply: Subscapular and circumflex scapular arteries

Daily uses: Brushing hair.

strengthening exercises: Shoulder external rotation.

stretches Internal rotation stretch.

Related injuries: Rotator cuff injuries.

Related muscles: Supraspinatus, Infraspinatus, Subscapularis, Teres major.

Closed Packed Position

The closed-packed position of the GH Joint is Abduction and External Rotation.

Open Packed Position

- The open-packed position of the GH Joint is around 50 degrees of Abduction with slight Horizontal Adduction and External Rotation.

- However, the point of maximal capsular laxity has been found to be 39 degrees of Abduction in the Scapular Plane, which suggests that the open-packed position may be close to a neutral position of the shoulder.

Capsular Pattern

A capsular pattern of the GH joint is characterized by external rotation being the most limited, followed by abduction, internal rotation, and flexion

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

- The glenohumeral joint receives vascular supply via the posterior and anterior circumflex humeral arteries, both of which are branches of the axillary artery.

- The predominant arterial blood supply to the humeral head is via the posterior humeral circumflex artery.

- The arcuate artery is the extension/continuation of the ascending branch of the anterior humeral circumflex.

- It enters the bicipital groove and supplies most of the humeral head. A branch of the thyrocervical trunk, the subscapular arteries, and its branches, also contribute to the blood supply of the shoulder.

- The majority of the lymph nodes in the upper extremity are located within the axilla.

- These can be divided based on location into five main groups: pectoral, subscapular, humeral, central, and apical. Efferent vessels coming from the apical axillary nodes travel through the cervico-axillary canal and then converge to form the subclavian lymphatic trunk.

- This trunk will either continue to enter the right venous angle or drain directly into the thoracic duct on the right and left, respectively.

- Removal and analysis of axillary lymph nodes is often an essential tool in the staging of breast cancers.

- The interruption of lymphatic drainage from the upper limb can, however, result in lymphoedema, a condition where accumulated lymph in the subcutaneous tissue leads to painful swelling of the upper limb.

Nerves:

- Innervation of the glenohumeral joint is provided by the suprascapular, lateral pectoral, and axillary nerves.

- All of the nerves supplying the glenohumeral joint originate from the brachial plexus which is a network of nerves formed by the ventral rami of the lower four cervical nerves and the first thoracic nerve [C5, C6, C7, C8, and T1]

Assessment of Shoulder Joint

- Check active movements

- Flexion and Extension

- Abduction and Adduction

- Observe the patient from the back to note symmetry and smoothness of scapula-thoracic movements

- Internal rotation (hands behind back) and external rotation (hands behind head)

- Assess rotator cuff muscles

Special Tests

- For dislocation/subluxation of the shoulder

- Apprehension test: The patient is made to STAND and the examiner stands behind the patient’s index shoulder.

- The shoulder is brought in 900 abduction and 900 external rotation.

- For right shoulder, the examiner’s right hand supports the elbow and can further rotate externally whereas the fingers of the left hand are kept in front of the anterior joint line of the shoulder while the thumb is kept over the posterior part of the head of the Humerus.

- Then the head is pushed forward gently which may push the head out in abducted and externally rotated position leading to apprehension over the face of the patient.

- Relocation-release test: The same test is done in SUPINE.

- The arm is taken in 900 abduction and 900 ER. The examiner holds the right elbow by his left hand and keeps his right hand over the patient’s right shoulder.

- The right hand is used to push (relocate) the head posteriorly and the arm is kept in AB-ER position. Gradually, extension is increased while keeping the hand still in front of the shoulder, and the patient remains relaxed.

- However, the examiner gently releases his hand in front of the shoulder to let the head of the humerus move anteriorly.

- This causes the release of the head anteriorly and makes the patient apprehensive of dislocation

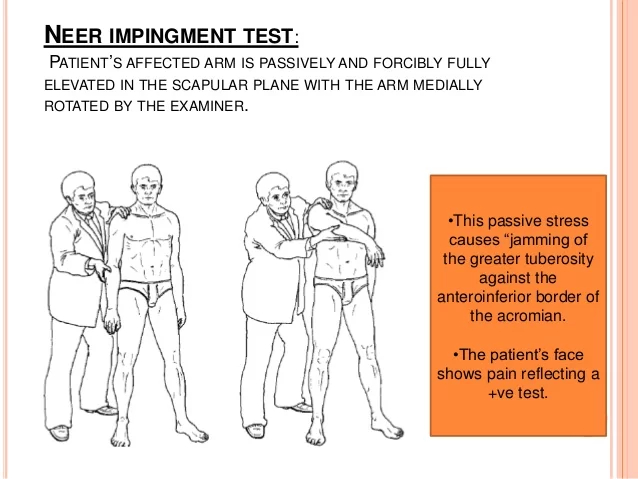

- For Impingement and subacromial bursitis:

- Neer’s Sign: In a normal situation, the Patient’s shoulder can be brought in gradual forward flexion till 1800flexion.

- However, in case of impingement, he/she complains of pain usually after 140-1500 of flexion indicating impingement.

- Neer’s test: when 2-5 ml of xylocaine is injected into the subacromial space, the pain due to impingement decreases.

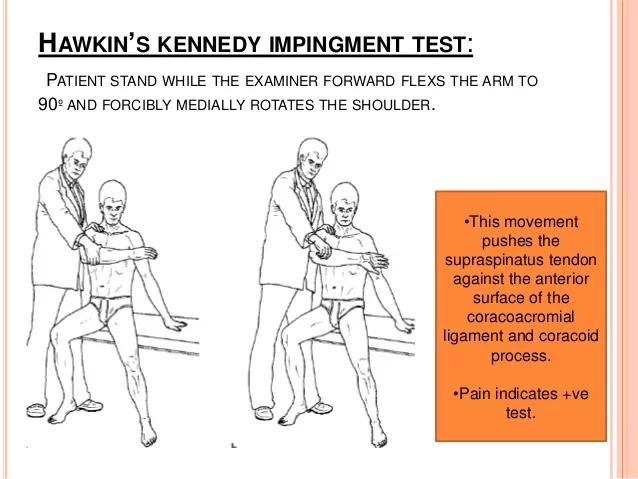

- Hawkin’s sign:

- It is performed to test “subacromial bursitis”. The shoulder is brought in 900 forward flexion followed by elbow flexion till 900. The shoulder is internally rotated. The patient complains of pain in internal rotation indicating subacromial bursitis.

- For rotator cuff tear:

Full can test: For supraspinatus tear

- The shoulder is brought in 60-700 of flexion and abduction with neutral rotation such that the thumb points upwards.

- Then, the patient is asked to lift his arm in a flexion or upward position while the examiner gives resistance to his movement.

- Any pain and weakness in this maneuver is suggestive of supraspinatus tear

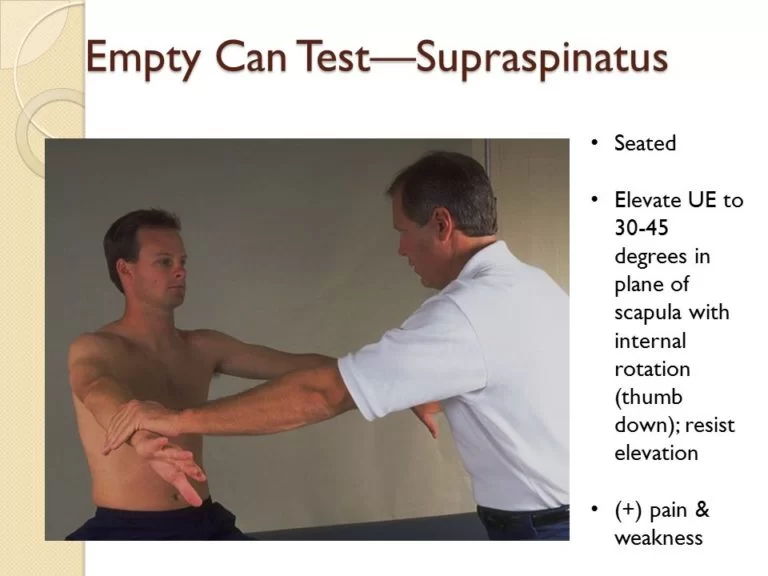

Supraspinatus (by ‘Empty Can’ test)

- Shoulder flexed forwards to 90 degrees and slightly abducted with internal rotation so that thumb is pointing to the ground (as if emptying a can) and attempt to continue bringing the arm up against resistance

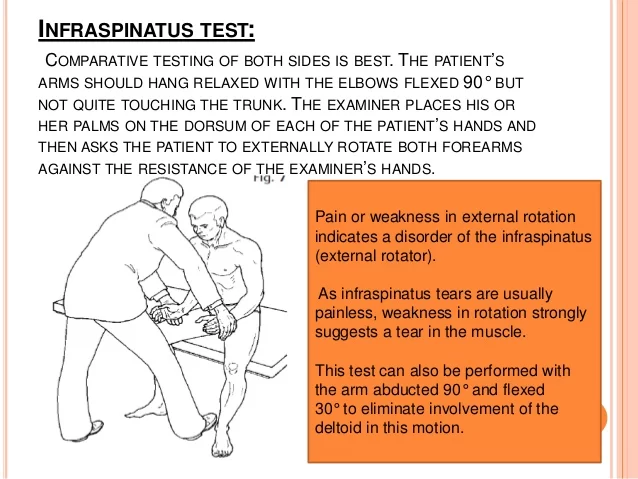

External rotation-lag test: For infraspinatus tear

- The shoulder is kept adducted and then externally rotated, and then it is released with a jerk.

- If the shoulder returns to internal rotation, it indicates weakness in the external rotator i.e. infraspinatus.

Infraspinatus Muscle:

- Assess resisted external rotation. Ask the patient to tuck their elbows into sides and externally rotate their forearm against your hand

Belly press sign: For subscapularis tear

- The patient is asked to press his belly with both hands and he is asked to bring his elbows forward while the examiner pushes the elbow backward.

- Any weakness or tears of the subscapularis lead to the elbow falling backward.

Subscapularis (by Gerber’s ‘Lift Off’ test)

- Hand placed in the small of the back with palm facing outwards and attempt to push against examiner’s hand

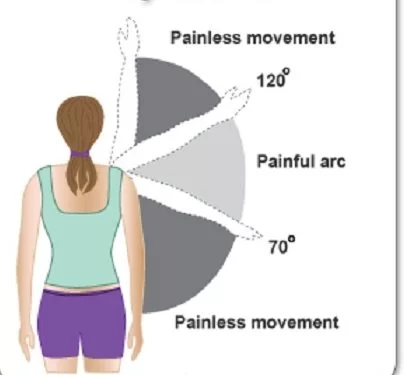

‘Painful Arc’ test (positive in supraspinatus tendinopathy, subacromial bursitis, and ACJ osteoarthritis)

- When the patient abducts their shoulder, the pain is worst during the middle arc

Scarf Test (positive in ACJ osteoarthritis)

- Ask the patient to place the hand of the side you are examining on the contralateral shoulder and then push the elbow superiorly to compress the acromium against the lateral end of the clavicle

Winging of the scapula (positive in long thoracic nerve palsy)

- Get the patient to push the hand against a wall whilst standing and look for the lifting of the scapula of the thoracic wall due to weak serratus anterior muscle

- For superior labral anterior-posterior tear (SLAP)

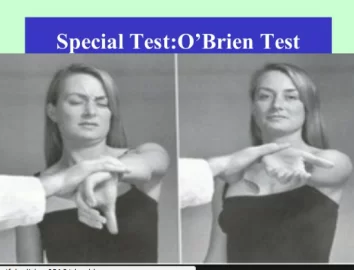

- O’Brien test: The shoulder is brought in 900 flexion, adducted by 100 and then internally rotated completely with the thumb pointing downwards. Then patient is asked to lift his hand upwards while the examiner gives downward resistance. Any weakness and or pain is indicative of a SLAP tear

(Note: SLAP tears are present in young patients with pain and inability to throw objects)

- For biceps tendon pathology: bicipital tendinitis

- Speed’s test: The shoulder is brought in 900 flexion with neutral in abduction or adduction with the forearm in supination. Then, the patient is asked to further flex the shoulder. Any pain in the bicipital groove or forearm is considered to be pathologic for bicipital tendinitis

- For acromioclavicular joint arthritis

- Cross chest adduction test (scarf test): With the elbow flexed, the shoulder is 900 flexed and adducted and the hand is made to touch the opposite shoulder. Any pain over the ACJ area is considered to be quite specific for ACJ arthritis.

Clinical Importance

Common conditions affecting shoulder with salient features

- Recurrent anterior dislocation

- Affects young patients

- May be associated with ligament laxity

- Presents with: Mostly traumatic recurrent dislocation, occasionally atraumatic

- Apprehension & relocation-release test positive

- Pathologically: Antero-inferior labral tear (Bankart lesion) along with posterolateral head impaction injury (Hill Sach’s lesion)

- Needs surgical stabilization: Arthroscopic/open Bankart repair

*Posterior dislocation is often seen in epileptics, after electric shock!

- Treatment typically involves analgesics and closed reduction, with some patients requiring subsequent surgical correction especially those with concurrent soft tissue injuries.

- The axillary nerves course within close proximity of the glenohumeral joint and wrap around the neck of the humerus, and can incur damage during dislocation or subsequent attempts at reduction of the dislocated joint.

- Injury to the axillary nerves causes a loss of sensation over the lateral shoulder and paralysis of the deltoid.

- Hill-Sachs lesions (impaction fracture of the posterolateral humeral head against anteroinferior glenoid) and Bankart lesions (detachment of antero-inferior labrum with or without an avulsion fracture) can also occur following anterior dislocation.

- The recurrence rate of glenohumeral joint dislocation is approximately 50% on average; however, there is a significant increase in the risk of reoccurrence at a younger age of initial dislocation.

- A SLAP tear (superior labrum anterior to posterior) is a rupture in the glenoid labrum.

- SLAP tears are characterized by shoulder pain in specific positions, pain associated with overhead activities such as tennis or overhand throwing sports, and weakness of the shoulder.

- Frozen shoulder/ adhesive capsulitis/peri arthritis shoulder

- Affects middle age: 40-55 years

- Presents with: Pain and severe loss of ROM (active and passive)

- Pathologically: Three stages affecting capsule and synovium

- Freezing: severe pain

- Frozen: pain & loss of ROM

- Thawing: decreased pain, increased ROM

- Clinical: severe loss of ROM and painful ROM

- Diagnosis by MRI/USG

- Treatment: NSAIDs, physiotherapy, intraarticular steroid injection, manipulation under general anaesthesia, or arthroscopic capsular release.

- Rotator cuff tendinopathy

- Affects middle age: 40-55 years

- Presents with: Mostly pain and mild loss of ROM mostly at extremes (active and passive)

- Pathologically: tendinopathy of supraspinatus & or infraspinatus

- Clinical signs: Neer’s and Hawkins’s positive

- Cuff integrity test: equivocal

- Diagnosis by MRI/USG

- Treatment: NSAIDs, physiotherapy, subacromial steroid injection, rarely arthroscopic subacromial decompression with debridement of frayed tendon and subacromial bursa excision.

- Rotator cuff tear

- Affects old age: 50 years onwards unless traumatic which can happen at any age

- Presents with: Pain with difficulty in elevating arm

- Pathologically: Tear of one or more rotator cuff tendons from its attachment over the tuberosity

- Clinically:

- Gross loss of active movements but usually passive ROM is preserved

- Full can and / ER lag test and/ belly press sign positive

- Diagnosis by MRI/USG

- Treatment:

- Smaller tears: conservative treatment: reduce pain, physiotherapy

- Larger tears or ones that do not respond to rehabilitation need surgical repair

- Acromioclavicular joint arthritis

- Affects adults, and manual workers: mostly after 45 years

- Presents with: Pain with active abduction usually beyond 900 abduction

- Tenderness + over ACJ

- Pathologically: Acromioclavicular joint arthritis

- Diagnosis: plain radiograph, MRI

- Treatment:

- Conservative: NSAIDs, physiotherapy, intra ACJ steroid injection, activity modification

- Surgical excision of ACJ if conservative treatment fails

- Glenohumeral joint (GHJ) arthritis

- Affects older patients: mostly after 65 years

- Presents with: Pain and difficulty in movement (similar to frozen shoulder but duration is longer and age is usually more than that of frozen shoulder)

- Pathologically: GH joint arthritis

- Clinically:

- Both active and passive ROM decreased

- Crepitus while ROM

- Tenderness + over anterior joint line

- Diagnosis: plain radiograph, CT scan, MRI

- Treatment:

- Conservative: NSAIDs, physiotherapy, intra-articular steroid injection, activity modification

- Arthroscopic debridement of GH joint for early stages of GH arthritis

- Total shoulder replacement for advanced cases

- Painful arc syndrome (PAS)

It is NOT a diagnosis per se. Many conditions can cause painful arc syndrome. It is characterized by painful abduction only in an arc of complete abduction wherein the initial and later parts of abduction are painless.

The following conditions can cause PAS

- Subacromial bursitis

- Rotator cuff tendinopathy

- Rotator cuff tears

- Greater tuberosity avulsion malunion

The clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of PAS are dependent upon the underlying condition

This type of injury often requires surgical repair.

- Subacromial bursitis is a painful condition caused by inflammation which often presents a set of symptoms known as subacromial impingement.

- Osteoarthritis: The common “wear-and-tear” arthritis that occurs with aging. The shoulder is less often affected by osteoarthritis than the knee.

- Rheumatoid arthritis: A form of arthritis in which the immune system attacks the joints, causing inflammation and pain. Rheumatoid arthritis can affect any joint, including the shoulder.

- Gout: A form of arthritis in which crystals form in the joints, causing inflammation and pain. The shoulder is an uncommon location for gout.

- Shoulder impingement: The acromion (edge of the scapula) presses on the rotator cuff as the arm is lifted. If inflammation or an injury in the rotator cuff is present, this impingement causes pain.

- Shoulder tendonitis: Inflammation of one of the tendons in the shoulder’s rotator cuff.

- Shoulder bursitis: Inflammation of the bursa, the small sac of fluid that rests over the rotator cuff tendons. Pain with overhead activities or pressure on the upper, and outer arms are symptoms.

- Labral tear: An accident or overuse can cause a tear in the labrum, the cuff of cartilage that overlies the head of the humerus. Most labral tears heal without requiring surgery.

TREATMENT

- Treatment will depend on the cause and severity of the shoulder pain. Some treatment options include physical or occupational therapy, a sling or shoulder immobilizer, or surgery.

- Your doctor may also prescribe medication such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications or corticosteroids. Corticosteroids are powerful anti-inflammatory drugs that can be taken by mouth or your doctor can inject them into your shoulder.

- If you’ve had shoulder surgery, follow after-care instructions carefully.

- Some minor shoulder pain can be treated at home. Icing the shoulder for 15 to 20 minutes three or four times a day for several days can help reduce pain. Use an ice bag or wrap ice in a towel because putting ice directly on your skin can cause frostbite and burn the skin.

- Resting the shoulder for several days before returning to normal activity and avoiding any movements that might cause pain can be helpful. Limit overhead work or activities.

- Other home treatments include using over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications to help reduce pain and inflammation and compressing the area with an elastic bandage to reduce swelling.

- exercises to strengthen weakened muscles, change their co-ordination and improve function

- advice on improving shoulder, neck, and spine posture

- exercises to ease or prevent stiffness

- exercises to increase the range of joint movement

- applying adhesive tape to the skin to reduce the strain on the tissues, and to help increase your awareness of the position of the shoulder and shoulder blade

- manual treatments to the soft tissues and joints – such as massage and manipulation.

Shoulder stretch

- Squeeze your shoulder blades back and together and hold for five seconds.

- Pull your shoulder blades downward and hold for five seconds. Relax and repeat 10 times.

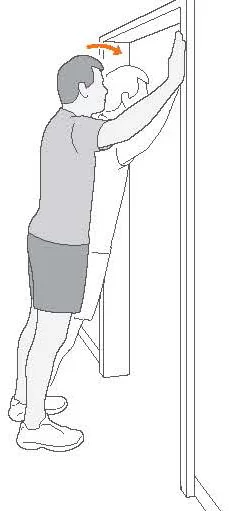

Door press (a)

- Stand in a doorway with your elbow bent at a right angle and the back of your wrist against the door frame.

- Try to push your arm outwards against the door frame. Hold for 5 seconds. Do 3 sets of 10 repetitions on each side.

Door press [B]

- Use your other arm and, still with your elbow at a right angle, push your palm towards the door frame.

- Hold for 5 seconds. Do 3 sets of 10 repetitions on each side.

Shoulder circle

- Stand with your good hand resting on a chair.

- Let your other arm hand down and try to swing it gently backward and forwards and in a circular motion.

- Repeat about 5 times.

- Try this 2-3 times a day.

FAQs

The sternoclavicular (SC), acromioclavicular (AC), scapulothoracic, and glenohumeral joints are the four joints that make up the shoulder.

The major joint, known as the glenohumeral joint, resembles a golf ball resting on a tee. It functions to provide a wide range of motion for the following movements: adduction (arms across the body), extension (arms reaching back), abduction (arms to the sides), and forward flexion (arms in front).

Acromion. the highest point or roof of the shoulder, produced by the scapula in part. tendon. the robust tissue cords that attach muscles to bones. A collection of tendons called the rotator cuff tendons attaches the humerus to the lowest layer of muscle.

The shoulder joint is a ball and socket joint, meaning that one bone’s rounded, ball-like end fits into another bone’s cup-shaped depression. Any direction of movement is possible with this joint. The hip also has a joint of this kind.

43 Comments