Hip Joint

Table of Contents

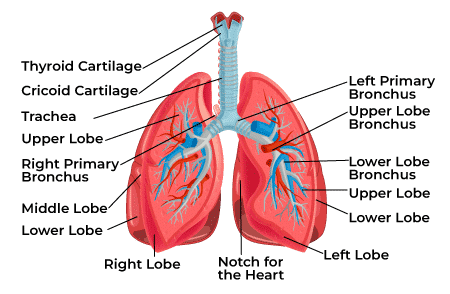

Introduction:

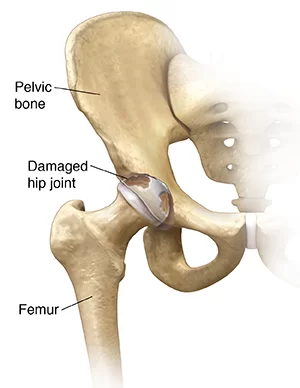

The hip joint is a ball-and-socket joint that connects the thigh bone (femur) to the pelvis, enabling a wide range of movement. It plays a crucial role in supporting the body’s weight and facilitating activities like walking, running, and jumping.

- The hip joint is a ball and socket synovial joint, formed by an articulation between the pelvic acetabulum and the head of the femur.

- The hip joint is the articulation of the pelvis with the femur, which connects the axial skeleton with the lower extremity.

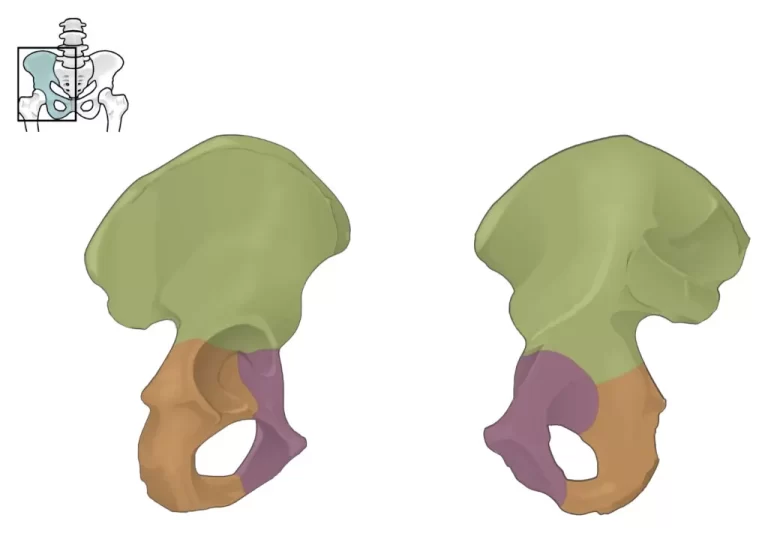

- The adult os coxae, or hip bone, is formed by the fusion of the ilium, the ischium, and the pubis, which occurs by the end of the teenage years.

- The 2 hip bones form the bony pelvis, along with the sacrum and the coccyx, and are united anteriorly by the pubic symphysis.

- It forms a connection from the lower limb to the pelvic girdle, and thus is designed for stability and weight-bearing – rather than a large range of movement.

- Bands of tissue, called ligaments, connect the ball to the socket, stabilizing the hip and forming the joint capsule.

- The joint capsule is lined with a thin membrane called synovium, which produces a viscous fluid to lubricate the joint.

- Fluid-filled sacs called bursae provide cushioning where there is friction between muscle, tendons and bones.

Structures of the Hip Joint :

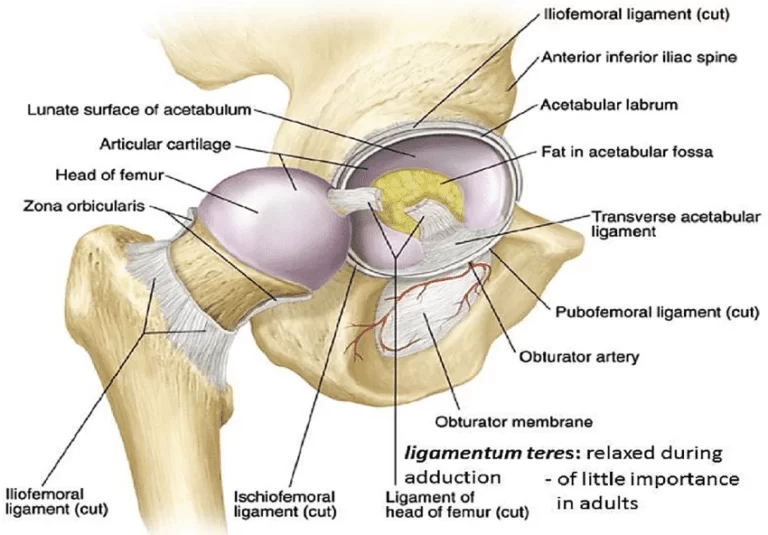

Articulating Surfaces :

- The hip joint consists of an articulation between the head of femur and acetabulum of the pelvis.

- The acetabulum is a cup-like depression located on the inferolateral aspect of the pelvis.

- Its cavity is deepened by the presence of a fibrocartilaginous collar – the acetabular labrum.

- The head of femur is hemispherical, and fits completely into the concavity of the acetabulum.

- Both the acetabulum and head of femur are covered in articular cartilage, which is thicker at the places of weight bearing.

- The capsule of the hip joint attaches to the edge of the acetabulum proximally.

- Distally, it attaches to the intertrochanteric line anteriorly and the femoral neck posteriorly.

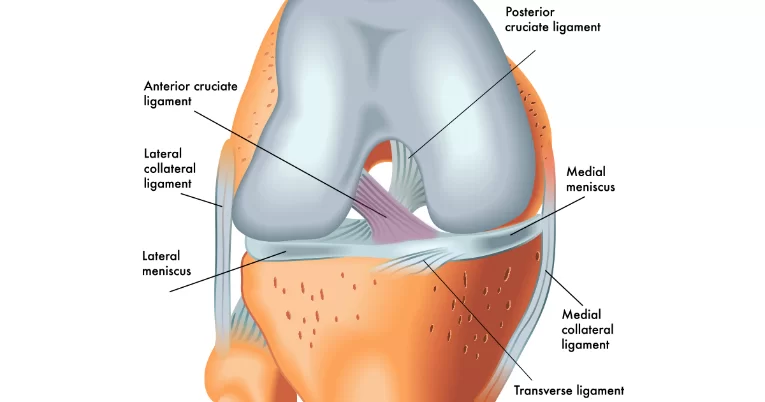

Ligaments:

- The ligaments of the hip joint act to increase stability.

- They can be divided into two groups – intracapsular and extracapsular:

Intracapsular:

- The only intracapsular ligament is the ligament of head of femur.

- It is a relatively small structure, which runs from the acetabular fossa to the fovea of the femur.

- It encloses a branch of the obturator artery (artery to head of femur), a minor source of arterial supply to the hip joint.

Extracapsular:

- There are three main extracapsular ligaments, continuous with the outer surface of the hip joint capsule:

- Iliofemoral ligament – arises from the anterior inferior iliac spine and then bifurcates before inserting into the intertrochanteric line of the femur.

- It has a ‘Y’ shaped appearance, and prevents hyperextension of the hip joint.

- It is the strongest of the three ligaments.

- Pubofemoral – spans between the superior pubic rami and the intertrochanteric line of the femur, reinforcing the capsule anteriorly and inferiorly.

- It has a triangular shape, and prevents excessive abduction and extension.

- Ischiofemoral– spans between the body of the ischium and the greater trochanter of the femur, reinforcing the capsule posteriorly.

- It has a spiral orientation, and prevents hyperextension and holds the femoral head in the acetabulum.

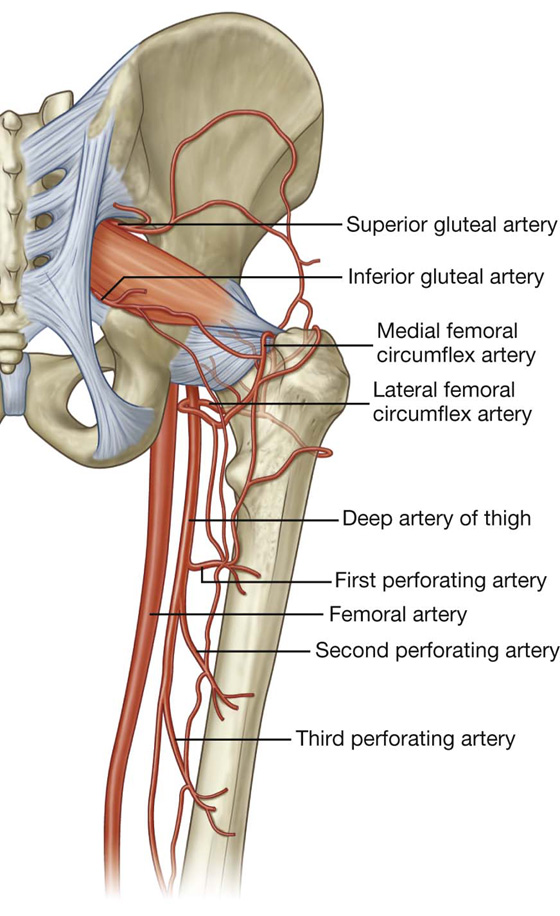

- Neurovascular Supply

- The arterial supply to the hip joint is largely via the medial and lateral circumflex femoral arteries – branches of the profunda femoris artery (deep femoral artery).

- They anastomose at the base of the femoral neck to form a ring, from which smaller arteries arise to supply the hip joint itself.

- The medial circumflex femoral artery is responsible for the majority of the arterial supply (the lateral circumflex femoral artery has to penetrate through the thick iliofemoral ligament).

- Damage to the medial circumflex femoral artery can result in avascular necrosis of the femoral head.

- The artery to head of femur and the superior/inferior gluteal arteries provide some additional supply.

- The hip joint is innervated primarily by the sciatic, femoral and obturator nerves.

- These same nerves innervate the knee, which explains why pain can be referred to the knee from the hip and vice versa.

Stabilising Factors:

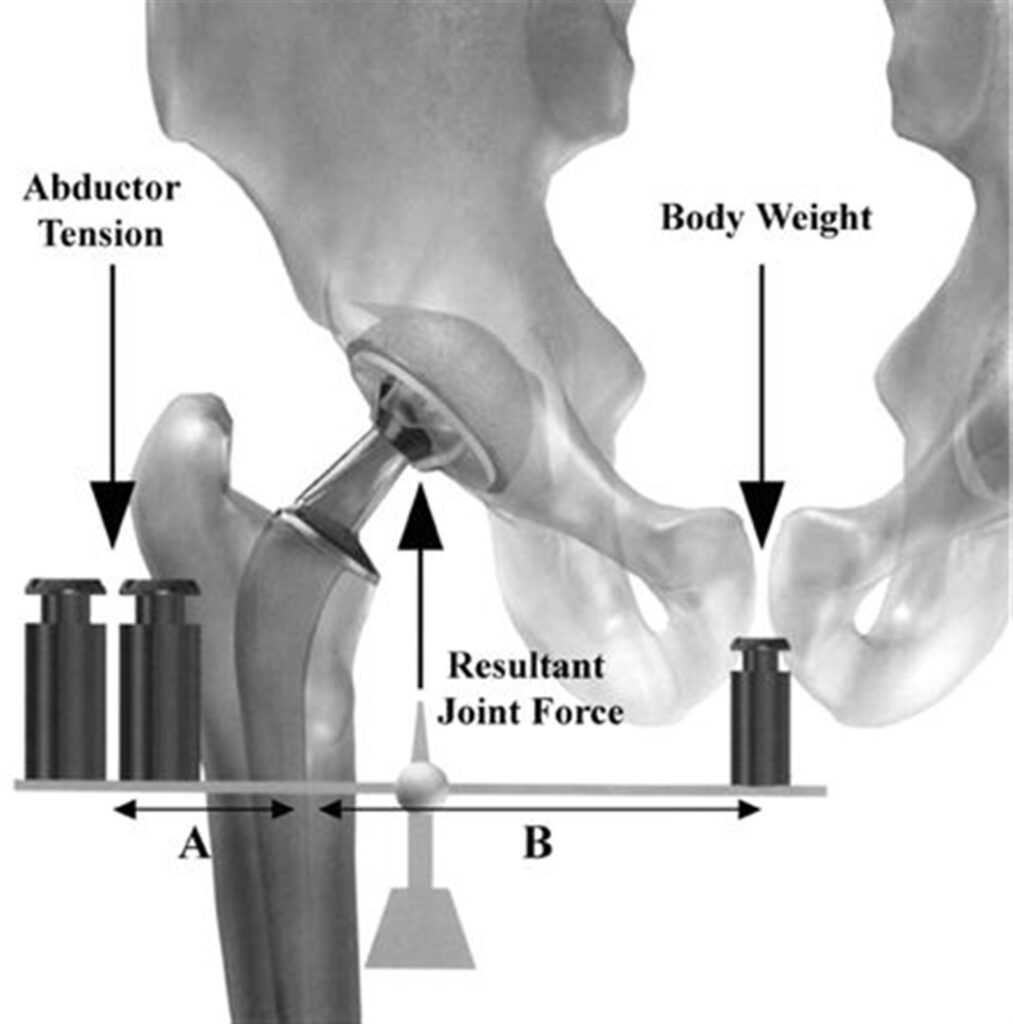

- The primary function of the hip joint is to weight-bear.

- There are a number of factors that act to increase stability of the joint.

- The first structure is the acetabulum.

- It is deep, and encompasses nearly all of the head of the femur.

- This decreases the probability of the head slipping out of the acetabulum (dislocation).

There is a horseshoe shaped fibrocartilaginous ring around the acetabulum which increases its depth, known as the acetabular labrum.

- The increase in depth provides a larger articular surface, further improving the stability of the joint.

- The iliofemoral, pubofemoral and ischiofemoral ligaments are very strong, and along with the thickened joint capsule, provide a large degree of stability.

- These ligaments have a unique spiral orientation; this causes them to become tighter when the joint is extended.

In addition, the muscles and ligaments work in a reciprocal fashion at the hip joint:

- Anteriorly, where the ligaments are strongest, the medial flexors (located anteriorly) are fewer and weaker.

- Posteriorly, where the ligaments are weakest, the medial rotators are greater in number and stronger – they effectively ‘pull’ the head of the femur into the acetabulum.

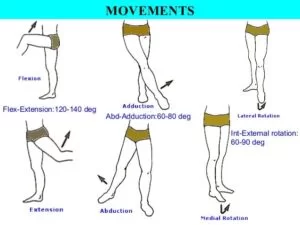

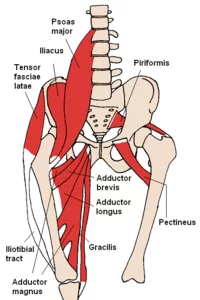

Movements and Muscles :

- The movements that can be carried out at the hip joint are listed below, along with the principle muscles responsible for each action:

- Flexion – iliopsoas,

- Rectus femoris, sartorius, pectineus

- Extension – gluteus maximus; semimembranosus, semitendinosus and biceps femoris (the hamstrings)

- Abduction – gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, piriformis and tensor fascia latae

- Adduction – adductors longus, brevis and magnus, pectineus and gracilis

- Lateral rotation – biceps femoris, gluteus maximus, piriformis, assisted by the obturators, gemilli and quadratus femoris.

- Medial rotation – anterior fibers of gluteus medius and minimus, tensor fascia lata

- The degree to which flexion at the hip can occur depends on whether the knee is flexed – this relaxes the hamstring muscles, and increases the range of flexion.

- Extension at the hip joint is limited by the joint capsule and the iliofemoral ligament.

- These structures become taut during extension to limit further movement.

Clinical Relevance: Dislocation of the Hip Joint:

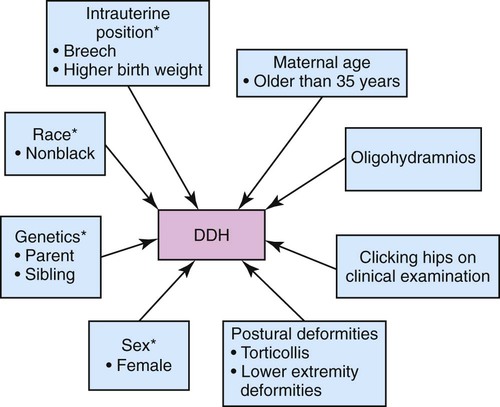

Congenital Dislocation:

- Congenital hip dislocation occurs as a result of developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH).

- It occurs when the Acetabulum is shallow as a result of failure to develop properly in utero

Common clinical features include:

- Limited abduction at the hip joint

- Limb length discrepancy – the affected limb is shorter

- Asymmetrical gluteal or thigh skin folds

- DDH is usually treated with a Pavlik harness.

- This holds the femoral head in the acetabular fossa and promotes normal development of the hip joint.

- Surgery is indicated in cases that do not respond to harness treatment.

Acquired Dislocation:

- Acquired dislocations of the hip joint are relatively uncommon, owing to the strength and stability of the joint.

- They usually occur as a result of trauma, but it can occur as a complication following Total Hip Replacement or hemiarthroplasty.

There are two main types of acquired hip dislocation:

- posterior and anterior:Posterior dislocation (90%)– the femoral head is forced posteriorly, and tears through the inferior and posterior part of the joint capsule, where it is at its weakest.

- The affected limb becomes shortened and medially rotated.

- The sciatic nerve runs posteriorly to the hip joint, and is at risk of injury (occurs in 10-20% of cases).

This is often associated with anterior femoral head and posterior wall fractures

- Anterior dislocation(rare) – occurs as a consequence of traumatic extension, abduction and lateral rotation.

- The femoral head is displaced anteriorly and (usually) inferiorly in relation to the acetabulum.

The hip is surrounded by large muscles that support the joint and enable movement. They include:

• Gluteals – muscles of the buttocks, located on the back of the hip

• Adductor muscles – muscles of the inner thigh, which pull the leg inward toward the opposite leg

• Iliopsoas muscle – a muscle that begins in the lower back and connects to the upper femur

• Quadriceps muscle – four muscles on the front of the thigh that run from the hip to the knee

• Hamstrings – muscles on the back of the thigh, which run from the hip to just below the knee

NERVES & VESSELS:

These include :

- The sciatic nerve at the back of the hip and femoral nerve at the front of the hip, and the femoral artery, which begins in the pelvis and passes by the front of the hip and down the thigh.

- The main function of the hip joint is to support the body weight in both standing and running or walking.

- The hips are very important for maintaining balance, and damages of the hip may cause impairments in all the function that this joint has, that can vary from easy to severe impairment.

Actions:

- Flexion (140 degrees),

- Extension (15 degrees),

- Abduction (40 degrees),

- Adduction (25 degrees),

- Internal rotation (35 degrees),

- External rotation (45 degrees)

Ligaments Outer : iliofemoral, ischiofemoral, pubofemoral

Inner: transverse acetabular, ligament of the femoral head

Related muscles:

- Flexors: iliopsoas, sartorius, tensor fasciae latae, rectus femoris, gluteus medius

- Extensors: gluteus maximus, medius and minimus, biceps femoris, semimembranosus

- Abductors: gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, piriformis

- Adductors: adductor longus, adductor brevis, adductor magnus, pectineus, gracilis, quadratus femoris

- Internal rotators: gluteus medius, gluteus minimu

- External rotators: obturator internus, obturator externus, superior gemellus, inferior gemellus, quadratus femoris, piriformis

Vascularization :

- Medial and lateral circumflex arteries, artery of the head of the femur (branches of the femoral artery)

Innervation:

- Anteriorly: femoral nerve

- Inferiorly: obturator nerve

- Laterally: sciatic nerve

- Posteriorly: superior gluteal nerve

Joint Capsule:

- The capsule of the hip joint has been described as strong and fibrous, but loose enough to accommodate a range of movements.

- It attaches to the anatomical structures known as the acetabular labrum, the transverse acetabular ligament and the intertrochanteric line of the femur.

- The proximal two thirds of the neck of the femur are encapsulated by the hip joint, whereas the distal third remains extracapsular.

- The iliofemoral ligament, the pubofemoral ligament and the ischiofemoral ligament all act to strengthen the mobile capsule.

Ligaments:

Outer Ligaments:

Iliofemoral ligament (Ligamentum iliofemorale):

- The iliofemoral ligament attaches itself to both the anterior inferior iliac spine and the acetabulum superiorly and the intertrochanteric line inferiorly, creating a ‘Y’ shape.

- It prevents hyperextension of the hip.

The ischiofemoral ligament :

- Originates in the rim of the acetabulum and turns laterally as it ascends to insert upon the inferomedial aspect of the greater trochanter.

- It functions in coherence with the iliofemoral ligament and also fixates the femoral head in the acetabulum.

- Prevents excessive medial rotation of the thigh.

The pubofemoral ligament:

- Arises from the pubic ramus and merges inferolaterally into the iliofemoral ligament, but may also have an attachment to the femoral neck.

- This ligament tightens during extension and abduction in order to limit the latter movement.

Inner Ligaments:

The transverse acetabular ligament :

- Runs over the acetabular notch and joins up with the inferior ends of the labrum.

- This ligament completes the acetabular ring.

- The ligament of the head of the femur is situated within the capsule but is extrasynovial.

- It arises from the acetabular notch and inserts upon the fovea of the femur.

- Within the ligament runs the artery that supplies the head of the femur.

Muscles:

Now a brief overview of the muscle groups, which are organised according to their primary function in relation to the hip joint.

Flexor muscles:

- The iliopsoas muscle, which consists of the psoas major muscle and the iliacus muscle.

- The psoas major originates from the vertebral bodies of T12- L4, the intervertebral discs between T12-L4 and the costal processes of L1-L5 vertebrae.

- The iliacus muscle originates from the iliac fossa.

- These individual muscle fascicles merge together and insert as a whole upon the lesser trochanter of the femur.

- The iliopsoas acts up the hip joint causing flexion and external rotation of the thigh.

- The psoas major also contributes to anterior and lateral flexion of the trunk.

Iliopsoas muscle (Musculus iliopsoas):

The sartorius muscle:

- Originating from the anterior superior iliac spine(ASIS) and the notch which is situated just below it, the sartorius muscle inserts itself at the medial surface of the proximal tibia via the pes anserinus.

The rectus femoris :

- Starts from the anterior inferior iliac spine and superior margin of the acetabulum.

- This muscle finds it’s insertion at the tibial tuberosity, via the patellar ligament.

- The rectus femoris functions by extending the leg at the knee joint and flexing the thigh at the hip joint.

The tensor fascia latae:

- Like the sartorius muscle also originates from the ASIS, however to a lesser extent it also arises from the anterior part of the outer lip of the iliac crest.

It inserts into iliotibial tract along the lateral thigh.

- It acts to stabilize the trunk on the thigh and also abducts, medially rotates and flexes the thigh at the hip joint, in addition to assisting in extension and external rotation of the leg at the knee joint.

Extensor muscles:

Gluteus maximus muscle (Musculus gluteus maximus ) :

- The gluteus maximus muscle originates the lateroposterior surface of the sacrum and coccyx, the ilium (behind the posterior gluteal line), the thoracolumbar fascia and the sacrotuberous ligament.

- It inserts into the iliotibial tract as well as into the gluteal tuberosity of the femur.

- The biceps femoris muscle has two heads.

- The long head arises from the inferomedial impression of the ischial tuberosity, while the short head arises from the lateral lip of the linea aspera and the lateral supracondylar line of the femur. These heads merge and insert as one tendon into the lateral side of the head of the fibula.

The semimembranosus muscle :

- It comes from both the superolateral aspect of the ischial tuberosity and terminates upon the posterior portion of the medial condyle of the tibia.

- The semitendinosis muscle arises from the posteromedial impression of the ischial tuberosity, and inserts at the medial surface of proximal tibia, below the medial condyle, via the pes anserinus.

- Abductor muscles

- The gluteus medius muscle originates between the anterior and posterior gluteal lines on the lateral surface of the ilium and inserts upon the lateral aspect of the greater trochanter of the femur.

- The gluteus minimus muscle passes between the anterior and inferior gluteal lines after arising from the lateral surface of the ilium and terminates upon the anterior surface of the greater trochanter of the femur.

- The piriformis muscle originates upon the anterior surface of the sacrum between S2-S4, and also from the sacrotuberous ligament. It inserts upon the apex of the greater trochanter of the femur.

Adductor longus muscle (Musculus adductor longus) :

- The adductor longus muscle originates from the body of the pubis, which is situated just below the pubic crest and inserts into the middle third of the linea aspera of the femur.

- The adductor brevis muscle

- arises from both the body and the inferior aspect of the pubic ramus and terminates on both the pectineal line as well as the proximal part of the linea aspera of the femur.

- The adductor magnus muscle comes from the inferior pubic ramus, as well as the ramus of the ischium.

- It also merges with fibers from the ischial tuberosity, which form part of the hamstring complex.

- These fibers attach themselves to the gluteal tuberosity, the linea aspera of the femur and the medial supracondylar line. The portion that adds to the hamstring fibers inserts upon the adductor tubercle.

- The pectineus muscle starts out at the pectineal line of the pubis and finishes at the pectineal line of the femur.

- The gracilis muscle arises from the body of the pubis and the inferior pubic ramus and terminates upon the superior part of the medial surface of the proximal tibia, via the pes anserinus.

- The quadratus femoris muscle comes from the lateral margin of the ischial tuberosity and inserts into the intertrochanteric crest of the femur.

- Internal rotator muscles

- The internal rotator muscles include the gluteus medius and the gluteus minimus muscles, in addition to some of the adductor muscles, namely adductor magnus.

External rotator muscles :

Obturator internus muscle (Musculus obturatorius internus) :

- The obturator internus muscle originates from the pelvic surface of the obturator membrane and the margins of the obturator foramen. It inserts into the medial surface of the greater trochanter of the femur.

obturator externus muscle :

- arises from the margins of the obturator foramen and the obturator membrane.

- It terminates in the trochanteric fossa of the femur.

superior gemellus muscle:

- comes from the outer surface of the ischial spine and stops at the medial aspect of the greater trochanter of the femur.

inferior gemellus muscle :

- arises from the upper margin of the ischial tuberosity and terminates upon the medial surface of the greater trochanter of the femur.

quadratus femoris muscle :

piriformis muscle :

Mechanics :

Abduction of thigh (Abductio femoris)

The range of movements of the hip joint are marked in degrees and are categorised by name:

Flexion: 140 degrees

Extension: 15 degrees

Abduction: 40 degrees

Adduction: 25 degrees

Internal rotation: 35 degrees

External rotation: 45 degrees

These ranges of movement occur when the knee is flexed at a right angle (90 degrees).

Blood Supply :

- There are two sets of arteries that contribute either majorly or minorly to the vascularisation of the joint capsule of the hip.

- The major contributing set contains the medial and lateral circumflex arteries that arise from the deep branch of the femoral artery.

- The minor contributing set singularly of the artery of the head of the femur.

Nerve Supply:

- The innervation of the hip joint comes anteriorly from the femoral nerve, inferiorly from the anterior division of the obturator nerve, laterally from the articular branch of the sciatic nerve and posteriorly from the nerve that runs to the quadratus femoris as well as the superior gluteal nerve.

Clinical Notes :

- Perthes disease, which is correctly termed Legg-Calve-Perthes disease and medically known as avascular necrosis is a disorder that is mostly found in children.

- The condition affects the head of the femur, when there is inadequate perfusion to the epiphysis, causing the bone to become necrotic.

- Eventually the blood flow returns to the area through revascularization and bone remodelling takes place.

- There are no somatic symptoms for this disease and the main complaint from patients with this condition is an increased risk of hip fracture.

Surgical Considerations:

- Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is an elective procedure for patients with hip pain secondary to degenerative conditions THA is a highly effective, reproducible procedure shown to relieve pain and restore function and improve quality of life in patient populations.

- THA is indicated for patients who have failed other conservative methods including corticosteroid injections, physical therapy, weight reduction, or previous surgical treatments.

Approaches :

- Any number of approaches can be utilized for the THA procedure.

- The three most common approaches are as follows:

Posterolateral :

- This is the most common approach for primary and revision THA cases.

- This dissection does not utilize a true internervous plane.

- The intermuscular interval involves blunt dissection of the gluteus maximus fibers and sharp incision of the fascia lata distally.

- The deep dissection involves meticulous dissection of the short external rotators and capsule.

- Care is taken to protect these structures as they are later repaired back to the proximal femur via trans-osseous tunnels.

- A major advantage of this approach is the avoidance of the hip abductors.

- Other advantages include the excellent exposure provided for both the acetabulum and the femur and the optional extensile conversion in the proximal or distal direction.

- Historically, some studies comparing this approach to the direct anterior (DA) approach have cited higher dislocation rates in the former approach.

- This remains an inconclusive and controversial as the literature has not established a definitive consensus, especially when comparing the posterior approach technique that utilizes an optimal soft tissue repair at the conclusion of the THA procedure.

Direct Anterior (DA) :

- The DA approach is becoming increasingly popular among THA surgeons.

- The internervous interval is between the tensor fascia lata (TFL) and sartorius on the superficial end, and the gluteus medius and rectus femoris (RF) on the deep side.

- DA THA advocates cite the theoretical decreased hip dislocation rates in the postoperative period and the avoidance of the hip abduction musculature.

- The disadvantages include the learning curve associated with the approach as the literature documents the decreased complication rates after a surgeon surpasses the more than 100-case mark.

- Other disadvantages include increased wound complications in particularly obese patients with large panni (without the use of an abdominal binder), difficult femoral exposure, the risk of lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN) paresthesias, and a potentially higher rate of intra-operative femur fractures.

- Finally, many surgeons need access to a specialized operating table with appropriately trained personnel and surgical technicians to assist in the procedure.

- Although the latter is not always required, learning to do the procedure on a regular operating table also requires a substantial learning curve that must be considered.

Anterolateral :

- Compared to the other approaches, the anterolateral (AL) approach is the least commonly used approach secondary to its violation of the hip abductor mechanism.

- The interval exploited includes that of the TFL and gluteus medius musculature.

- This may lead to a postoperative limp at the tradeoff of a theoretically decreased dislocation rate.

Clinical Significance :

Congenital Hip Dislocation/Dysplasia :

- Also known as developmental dysplasia of the hip, this can arise when there are problems with the development of the hip joint in utero.

- Risk factors include breech presentation, positive family history, and oligohydramnios.

- Diagnosis can be made via physical exam with the Barlow and Ortolani maneuvers which are used to assess joint stability. Additional common findings are leg length asymmetry as well as asymmetric inguinal skin folds.

- The ultimate goal of treatment is the open or closed reduction of the femoral head back into the acetabulum.

- The earlier treatment is initiated, the better the outcomes.

- Mild cases can correct spontaneously by 2 weeks.

- When subluxation persists more than 2 weeks, treatment is indicated.

- A standard treatment is the use of the Pavlik Harness which positions the hips into flexion and abduction for 6 weeks full-time followed by 6 weeks part-time.

Traumatic Conditions :

- Commonly seen in the setting of trauma, a posterior dislocation is seen in the setting of high-energy trauma or motor vehicle accidents (MVAs).

- The femoral head is transmitted posteriorly, injuring the hip joint capsule.

- The affected lower extremity presents in a shortened, internally rotated position.

- In all traumatic injuries, there is extensive soft tissue injury about the hip joint and capsule and in the vast majority of presentations, there will be an associated posterior wall (acetabular) fracture and/or femoral head fracture.

- The positioning of the hip often determines the associated acetabular injury.

- Patients will typically present with significant pain and inability to bear weight.

- Approximately 10% of cases may have concurrent damage to the sciatic nerve.

- Treatment consists of both nonoperative and operative measures.

- In the acute setting, the emergent closed reduction is recommended within 6 hours of the injury.

- Following a successful closed reduction, a CT scan is performed to assess and evaluate the extent of associated osseous injuries.

- In addition, the presence of incarcerated fragments in the joint is of utmost importance as appreciably large fragments will not only prevent complete reduction of the native hip joint but these fragments also potentially can cause further intra-articular damage and chondral injuries secondary to mechanical abrasion and pathologic contact/abutment.

- Irreducible dislocations, those with evidence of incarcerated fragments, and delayed presentations are treated via operative open reduction urgently.

- Open reduction with internal fixation is recommended for complex dislocations with evidence of acetabular or femoral fractures.

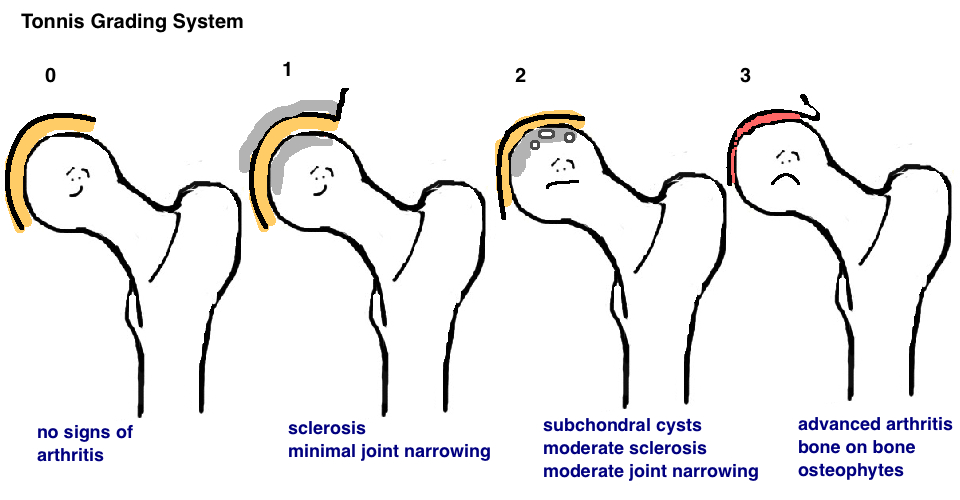

Osteoarthritis of the Hip:

- Most commonly presents in adults, greater than 40 years old.

- Symptoms include pain, disability, ambulatory dysfunction, and stiffness/contracture.

- The pain is typically felt in the anterior groin, occasionally including the buttocks and lateral thigh.

- Some patients can develop generalized hip referred pain of the knee.

- It is important to consider and/or rule out co-existing lumbar spinous pathology/radiculopathy, and ipsilateral knee conditions.

- The pathogenesis involves wear and tear on the joint cartilage, which over time, leads to decreased protective joint space.

- As bones begin to rub on one another, they attempt to make up for the lost cartilage and form bone spurs or osteophytes.

- Nonsurgical treatments involve lifestyle modifications such as weight loss, or minimizing activates that exacerbate pain. Physical therapies, the use of assistive devices, and medications such as NSAIDs, acetaminophen, and corticosteroids have also been shown to help.

- For patients whose pain is still irretraceable, surgical intervention may need to be required.

- Surgical options include osteotomy, hip resurfacing, and total hip replacement .

PHYSIOTHERAPY TREATMENTS :

PARTHES DISEASE :

- physiotherapy was applied in children with a mild course of the disease.

- Passive mobilisations for musculature stretching of the involved hip.

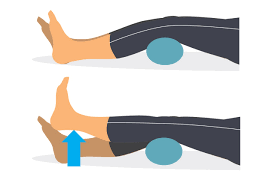

- Straight leg raise exercises, to strengthen the musculature of the hip involved for the flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction of muscles of the hip.

- They started with isometric exercises and after eight session, isotonic exercises.

- A balance training initially on stable terrain, and later on unstable terrain.

- It is recommended that supervised physical therapy is supplemented with a customized written home exercise program in all phases of rehabilitation.

- Begin with isometric exercise and progress to isotonic exercises in a gravity lessened position with further progression to isotonic exercises against gravity. It is appropriate to include concentric and eccentric contractions .

- Begin with 2 sets of 10 to 15 repetitions of each exercise , with progression to 3 sets of each exercise to be used .

- Local consensus would also do exercises to improve balance and gait and interventions to reduce pain.

OSTEOARTHRITIS OF HIP JOINT :

- When beginning an exercise program, it’s best to start slowly. Some examples of low-impact, non-strenuous exercise include:

Walking

- If you have balance problems, using a treadmill (with no incline) allows you to hold on. Walking at a comfortable pace — whether it’s indoors or outdoors — is an excellent low-impact exercise.

Water exercises

- Freestyle swimming provides a moderate workout. Walking in water up to your waist lightens the load on your joints while also providing enough resistance for your muscles to become stronger. This can greatly improve pain and daily function of the hips

Yoga

- Regular yoga can help improve flexibility of the joints, strengthen muscles, and lessen pain. Some yoga positions can add strain to your hips, so if you feel discomfort, ask your instructor for modifications. A class for beginners is a good place to start.

Tai chi

The slow, fluid movements of tai chi may relieve arthritis pain and improve balance. Tai chi is a natural and healthy stress reducer as well

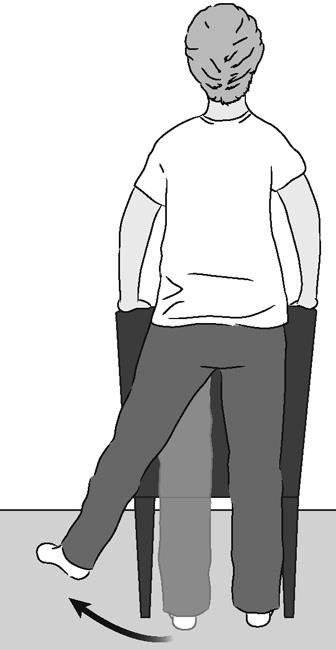

Muscle strengthening exercises

- Chair stand

- Bridge

- Hip extension

Flexibility exercises

- Gentle flexibility exercises, or range-of-motion exercises, help with mobility and reducing stiffness.

- Inner leg stretch

- Hip and lower back stretch

- Double hip rotation

Balance exercise

Aerobic exercise

- Aerobic exercise, also called cardio or endurance exercise, is activity that makes your heart beat faster

- speed walking

- vigorous swimming

- stationary bike

- aerobic dance

Tips to help relieve OA hip pain

- Listen to your body and adjust your activities as necessary.

- Stick with gentle exercises that can strengthen the muscles around your hips.

- If you feel increased pain, stop and rest. If joint pain continues hours after you’ve stopped, you are over exerting your hip.

- Increase your activity level throughout the day by walking whenever possible.

- Use over-the-counter anti-inflammatory medications for your hip pain.

- Make sure you get a good night’s sleep.

- Manage your weight: extra pounds can be a burden on your hip.

- Check with your doctor if you think it may be necessary to use a cane.

- Join a health club or exercise class to help you stay focused and active

55 Comments