Stress Fracture

Table of Contents

What is a stress fracture?

Stress injury can be classified depending on the diagnosis: early (stress reaction) or late (stress fracture). A stress reaction that can not be treated will develop into a stress fracture.

Stress fractures are tiny cracks in a bone that lead to fractures. They’re caused by repetitive force or stress. It does not result from a single severe impact. Still, repeated stress results in accumulated injury from repeated submaximal loading often from overuse — such as repeatedly jumping up and down or running long distances. Stress fractures may also develop from regular use of a bone that’s weakened by a condition such as osteoporosis. Because of this mechanism, it is an overuse injury in athletes.

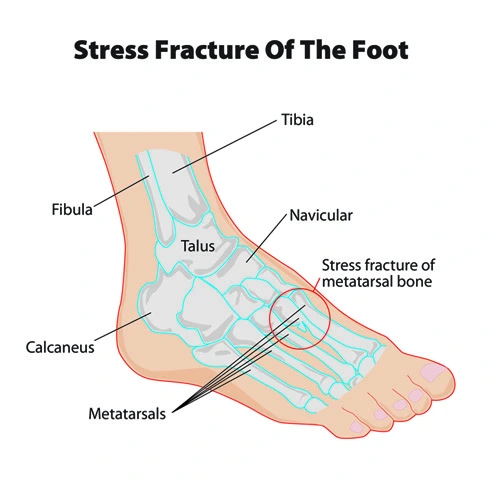

Stress fractures can be described as small cracks in the lower limb bone or hairline fractures. These foot fractures are sometimes called “march fractures” because of the prevalence of injury in soldiers while heavily marching.

Where does stress fracture occur?

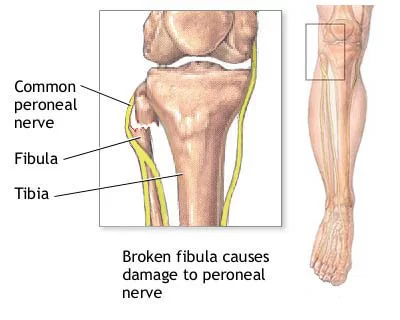

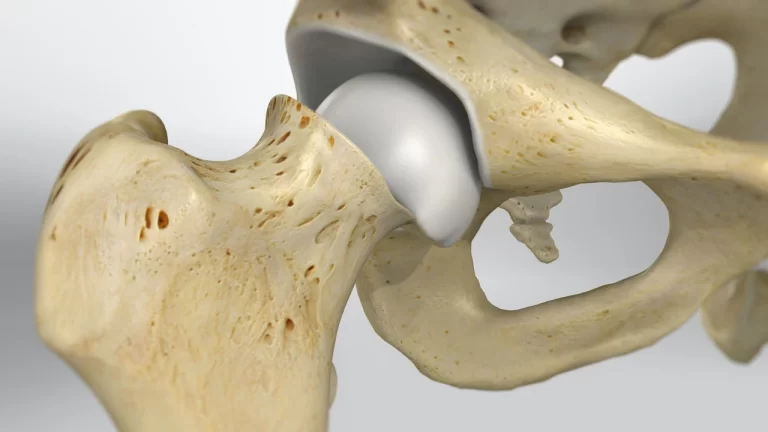

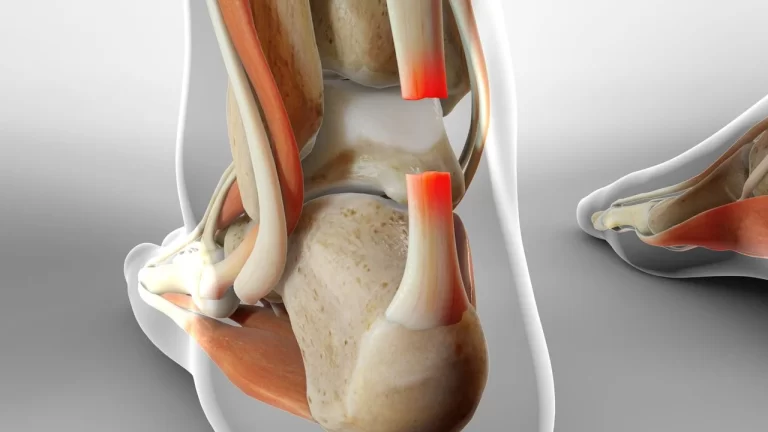

Stress fractures most commonly occur in weight-bearing bones of the lower leg, such as the tibia and fibula (bones of the lower leg), metatarsal(small bones), and navicular bones (bones of the foot)as a result of weight-bearing activities. Less common stress fractures occur in the femur, pelvis, and sacrum. Treatment usually consists of rest followed by a gradual return to exercise over a period of some months.

Track and field athletes and military recruiters carry heavy packs over long distances, but anyone can sustain a stress fracture. If you start a new exercise program, for example, you may develop stress fractures if you do too much in a short time.

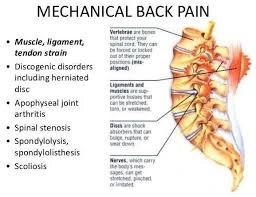

Stress fractures can also be seen in the heel (calcaneus), hip (proximal femur), and even lower back.

Causes and risk factors:

What are the Causes of a stress fractures?

Stress fractures often result from increasing the amount, frequency, or intensity of an activity too quickly.

Bone adapts slowly to increased loads through remodeling, a normal process that speeds up when the load on the bone raises. During remodeling, bone tissue is demolished (resorption), then reformed.

Bones subjected to unaccustomed force without taking enough time for recovery can resorb cells faster than your body and can replace them, which makes you more susceptible to stress fractures.

Risk factors:

Factors that may increase the risk of stress fractures include:

- Certain sports: Stress fractures are more common in people who engage in high-impact sports or athletes, such as track and field, basketball, tennis, dance, or gymnastics.

- Increased activity: Stress fractures often occur in people who suddenly shift from a normal lifestyle to an active training regimen or who rapidly increase the intensity, duration, or frequency of training sessions or exercises.

- Sex: Women, especially those who have irregular or absent menstrual periods, are at higher risk of developing stress fractures.

- Foot problems: People who have flat feet or high, rigid arches are more prone to develop stress fractures. Worn footwear contributes to the problem.

- Weakened bones: Conditions such as osteoporosis can weaken bones and make it easier for stress fractures to occur.

- Previous stress fractures: A patient who has had one or more stress fractures in the past puts you at a higher risk of having more.

- Lack of nutrients: Eating disorders and lack of vitamin D and calcium may make bones more likely to develop stress fractures.

Risk factors for stress fractures can be classified into two basic categories:

Extrinsic and Intrinsic.

Extrinsic factors that happen outside of the body. These can also be known as environmental (nature) factors. These factors can include:

- Practicing incorrect training or sport technique.

- Having too rapid of a training program or volume of activity or changing your activity level without a gradual break-in between training.

- Changing the surface you exercise on, such as going from a soft surface (like an indoor track) to outside on hard or concrete.

- Running on a track or road with a sloped surface or uneven surface.

- Using poor equipment or improper footwear (shoes that are too worn out, too flimsy, or too stiff) while walking.

- Doing the activity repeatedly in certain high-impact sports, such as:

- Long-distance running (tibia, hip).

- Basketball.

- Tennis.

- Track and field.

- Gymnastics (wrist stress fractures from weight bearing on hands/wrists, low back while carrying heavy weights).

- Dance (feet, low back).

- Having a poor diet that has an inadequate caloric intake for the need of sport.

- Having a low vitamin D level.

- Experiencing early specialization in sports. Athletes who play one sport year-round without a break are at risk of stress fractures.

Intrinsic factors are things that are related to the athlete or patient and not impacted by outside forces. These factors can

include:

- Age: Older people and athletes may have underlying bone density issues such as osteoporosis. Weakened bone will develop a stress fracture sooner than healthy bone.

- Weight: Both high and low BMI seem to be at risk for stress injuries. Some people with a low BMI or underweight may have weakened bones and a person with a high BMI doing repetitive loading with their body weight would also be at risk for injuries.

- Anatomy: Foot problems can affect when the way the foot strikes the ground. These foot problems can include bunions, blisters, tendonitis, and low or high arches in the foot.

- Muscle weakness, imbalances, or lack of flexibility can also be a factor in this condition.

- Sex: Females might be at risk if they have irregular menstrual periods or no periods.

- Medical conditions: Osteoporosis or other diseases that weaken bone strength and increase density (thickness). The weak or soft bones can not be able to handle the changes in activity.

Signs and Symptoms:

At first, the patient might barely notice the pain associated with a stress fracture, but it tends to worsen with time. The tenderness usually starts at a specific spot and reduces during rest. You might have to swell around the painful area.

The symptoms of a stress fracture may include:

- Symptoms usually have a gradual onset, isolated pain along the shaft of the bone.

- Pain, swelling, or aching at the site or surrounding the fracture.

- Tenderness may present when touched on the bone.

- When the pressure is applied to the bone, it may reproduce symptoms and have crepitus sound in well-developed stress fracture.

- Pain begins after starting an activity and then disappears with rest.

- Pain that presents throughout the activity and may not go away after the activity has ended.

- Pain that occurs while at rest, during normal activity, or with everyday walking in the leg.

- Pain is worse with hopping on one leg or an inability to shift weight/hop on the affected limb.

- If a stress fracture is not treated at an early stage (stress reaction), the pain can become worse. There is also a risk that the fracture may become displaced (the fractured part moves out of normal alignment). Certain stress fractures (hip bone) are considered “high-risk” stress fractures because they may have a poor outcome (such as needing surgery) if not identified early.

Diagnosis:

Doctors may sometimes diagnose a stress fracture from medical history, other activities, a medical examination, and a physical exam, but imaging tests are often needed.

X-rays:

It usually does not show evidence of any new stress fractures, but can be used approximately three weeks after the onset of pain when the bone begins to remodel.

Stress fractures often can’t be seen on regular X-rays taken shortly after the pain begins. It can take several weeks — and sometimes longer than a month — for evidence of stress fractures in the body to show on X-rays.

CT:

A CT scan, MRI, or 3-phase bone scan may be more effective for early diagnosis of fracture.

MRI:

MRI appears to be the most accurate diagnostic test for injury.

MRI uses radio waves and a strong magnetic field to find detailed images of bones and soft tissues. An MRI is considered the best way to diagnose stress fractures, as it shows a clear image. MRI can visualize lower-grade stress injuries (stress reactions) before an X-ray shows changes. This type of test is also better able to discriminate between stress fractures and soft tissue injuries.

Treatment of Stress fracture:

Treatment for stress fractures is needed. If you think you have a stress fracture, follow the:

The thing to do first is rest.

Stop any activities which may be contributing to the injury and pain.

Schedule an appointment to see a doctor. It is important to follow the treatment guidelines to prevent further injury.

If a stress fracture is not treated, the fracture may get worse and may displace. It can heal improperly and may lead to arthritis or even surgery. Definitely do not ignore the pain, ignoring the pain can lead to serious problems in the future, so it is important to see the doctor when you start feeling the pain.

Non-surgical treatment:

Home treatments:

Follow the RICE method:

- Rest to reduce pain

- Ice for five to ten minutes several times a day.

- Compression

- Elevation (above your heart level)

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen and aspirin can help with pain and swelling.

It’s important to seek further treatment from your doctor if the pain becomes worse or doesn’t get better with rest. The doctor chooses treatment that will depend on both the severity and location of your injury.

Medical treatment:

Depending on the injury, healing time in stress fractures can vary from 4 to 12 weeks or longer from the time activity is restricted. Initial treatment should include reducing activity level of pain-free functioning. Treatment should be started as soon as the injury is suspected because delayed treatment has been correlated with a prolonged return to activity.

- Rest: Rest is the most crucial part of treating a stress fracture. Avoiding the activity that caused the stress fracture, as well as any other high-impact activities that cause pain, allows the bone to heal.

- Modify activities: During this time, switch to activities that place less stress on the foot and leg. Swimming and cycling are good alternative activities that place less stress on the foot and mobility may continue. However, you should not resume any type of physical activity that involves your injured foot or ankle — even if it is low impact — without your doctor’s approval. Though it’s important to avoid high-impact activity, sports medicine doctors and physical therapists can help you find safe ways to stay active as recovery starts. Our doctors can provide access to specialized exercise equipment, such as gravity-reducing treadmills, that enable you to continue exercising or training without putting stress on the bones.

- Protective footwear: To reduce stress on the foot and leg, the doctor may recommend wearing protective footwear. These may be a stiff-soled shoe, a wooden-soled sandal, or a removable short-leg fracture brace shoe.

- Cast and Braces: Certain types of stress fractures may need additional stability. Doctors may apply a cast to your foot to keep your bones in a fixed position and to stable and remove the stress on your involved leg.

Doctors may recommend using crutches or a walking boot or brace for a few weeks to reduce or eliminate stress on the injured bone or leg. Our orthopedic specialists and orthotist can provide you with these devices and ensure that they fit you properly in your foot.

If a stress fracture is severe, which can occur if repeated stress occurs on the bone. After symptoms appear, the doctor may apply a plaster cast to the foot to immobilize the bone. Doctors usually recommend that you wear the cast for 4 to 6 weeks, but it depends on the extent of the injury, which is seen on imaging tests. A large or repeated stress fracture may take longer to heal.

Physical Therapy Treatment

Correct management needs to be specific to every person’s injury. Most of the cases, the initial management will include rest to allow the stress fracture to heal. In moderate to severe cases, this may involve the use of crutches or wearing a weight-bearing boot, to reduce the weight-bearing loads on bone.

Early stages,

Treatment includes- analgesia, modified weight-bearing, and activity modification including discontinuing the activities that affect injury. If the patient is not able to ambulate without pain, temporary immobilization is indicated.

Examples of activity modification include water fitness, cycling, and elliptical exercise to maintain the strength and fitness of the body. Progression, after a period of pain-free rest, involves a gradual return to activity over the subsequent weeks involving continued physical therapy.

Rehabilitation and strengthening, as well as a gradual return to functional activity, are extremely important to prevent or reduce the chance of re-injury. It is of key importance to develop a specific program to enable your patient to safely and efficiently return to their activity or sport again.

The patient’s symptoms should be monitored and the patient should be kept pain-free during the progression back to their activity. Pain should not worsen during or after stopping exercises.

If symptoms return, activity modification by reducing load, volume, and/or intensity or use of non-impact mode) and further investigation for other etiologies may be needed.

Phase 1: Acute phase (7-21 days)

Treatment modalities :

- Cryotherapy- reduce swelling and pain

- low-intensity pulsed ultrasound – decrease swelling

- Soft tissue mobilization

- Electric stimulation- strengthens muscle

Exercise:

Range of motion: It is less mobile from any weeks after injury, so ROM may be decreased. ROM exercises for various joints in the lower limb.

Muscle strengthening:

- Due to inactivity for short periods, there is weakness in the muscles of the legs leading to a new injury

- Main focus on gluteals- Sidelying straight leg raise

- Core strengthening exercise: planks, side planks, progression from standing to half kneeling and to kneeling.

- Ankle invertor and evertor

- Foot intrinsic muscle strengthening

- Upper body strengthening

Stretching:

- Stretching helps decrease the tightness of muscles.

- Stretching of hip flexors- Quadriceps, hamstring gastrocnemius, and soleus

Balance training:

Education for proper shoe selection, and nutrition important for the body

An orthotic shoe that helps to support a return to activity without pain as well as prevent a future stress fracture

Activities: Cycling or upper body ergometry

Phase 2 : Subacute phase( 4-6 weeks)

The main aim is to gradually return to a prior level of function

Modalities:

- Edema controlling treatment

Exercise:

Range of motion:

- Ankle Dorsiflexor ROM

Mobility:

- Stretching of Gastrocnemius and soleus

- Lower extremity kinetic chain mobility

Strengthening:

- Foot/ankle strengthening

- Progress balance activity by focusing on single-limb stability

- Single-leg heel raise

- Foot intrinsic strengthening in weight bear position

Hip strengthening: Double leg and single leg proximal stability exercises. It may include:

- Squats

- single leg squats

- Lunges with forward trunk lean

- step up

- step down

- lateral band walks

Activities:

- Swimming

- Deep water or pool running

- Encourage shock absorption strategies such as increasing step rate, step width, and forward trunk lean.

Phase 3 : Advanced strengthening(6-10 weeks)

Continue with the previous exercise program.

A good guideline is given to increase activity by no more than 15-20% per week.

Consider Return to Running program.

Modality:

- Continue as given in phases 1 and 2, needed for pain control

Exercises:

Plyometrics: emphasis on the soft landing and hip strategy

- For example,

- Double limb:

-Box jumps

-Drop jumps

-Forward jumps

-Tuck jumps - Single limb:

-Lunge hop

-Single box hop

-Drop with single-leg land

-Single forward hop

Strengthening:

- Foot/ankle strengthening- continue balance exercise and foot intrinsic strengthening in single limb weight-bearing position

- Hip strengthening- continue single limb proximal stability exercises in the hip.

Lower extremity mobility:

- Continue to address lower extremity kinetic chain mobility loss

Other Activities:

- Begin to return to running the program

Goals of Phase:

- Return to running

- Return to recreational/sporting activity

- Normal lower extremity kinetic chain strength and muscle length

Phase 4: (Return to all activities)

Continue with proper load management and progression to full activity while walking and running.

Total activity time 30 minutes.

Beginning with a warm-up for 2-5 minutes. A brisk walk followed by stretching

Beginning with walking for more time and running for less time compared to running.

For eg.

In week 1

DAY 1: 6 times -Walk for 4.5 min and run 0.5 min

DAY 2: 6 times -Walk for 4.0 min and run for 1 min

DAY 3: 6 times -Walk for 3.5 min and run for 1.5 min

In week 2

DAY 1: 6 times -Walk for 3.0 min and run 2.0 min

DAY 2: 6 times -Walk for 2.5 min and run for 2.5 min

DAY 3: 6 times -Walk for 2.0 min and run for 3.0 min

In week 3

DAY 1: 6 times -Walk for 1.5 min and run 3.5 min

DAY 2: 6 times -Walk for 1 min and run for 4.0 min

DAY 3: 6 times -Walk for 0.5 min and run for 4.5 min

In week 4

DAY 1: Run for 30 minutes

DAY 2: Run for 30 minutes

DAY 3: Run for 30 minutes

By completing Week 4, you may resume a gradual transition back to continuous running following a 2-minute warm-up walk and stretching. As you return to your pre-injury running level, training duration or intensity should be increased by no more than 10-20% per week to minimize the risk of injury recurrence. Be sure to continue your stretching program as instructed given by the therapist.

How to Prevent stress Fractures?

Such steps can help prevent a stress fracture:

- Once the patient feels pain, stop exercising or any activity. Only return to exercise if the patient feels pain-free. See a doctor as soon as possible if you have a persistent area of concern or discomfort.

- Use the correct sports equipment while training.

- Use proper footwear. Wear the proper running shoes. Running shoes should be replaced every 300-400 miles distance.

- Add new physical activities which decrease the load on foot (for example, switch running with swimming).

- Start new sports activities slowly and gradually increases the time, speed, and distance.

- When restarting a sport or any activity, reduce intensity by 50%. Follow the 10% rule: no increases of more than 10% per week.

- Make sure before starting activities, to do a proper warm-up and cool down.

- Practice muscle strength training to help prevent early muscle fatigue, and to help prevent the loss of bone density that comes with aging.

- Cross-train: Add low-impact activities to your exercise regimen to avoid repeating or stressing a particular part of your body.

- Follow a healthy diet full of calcium and vitamin D foods that will keep bones strong. A sports nutritionist can be helpful if you are extremely active and have any history of stress fractures.

- If you decide to increase your activity level, ask your doctor for a recommendation of how much to add and when to add activity.

- Optimize your bone health: If the patient has a known history of osteopenia, osteoporosis, or osteoporosis, discuss with your doctor how to medically manage these conditions. A stress fracture with a weaker bone is harder to heal faster.

- If pain or swelling returns, stop the activity that causes load and rest for a few days. If the pain continues, see the doctor again.

- Check with your doctor before starting an exercise program or before taking a job that will involve a higher level of physical activity than you are used to.

- Follow all the rules given by the doctor.

FAQs:

Can a physio treat stress fractures?

Physiotherapy will also focus on strengthening any loss you may have predisposed to when you have a stress fracture. You can expect a physiotherapist to help you with exercises, load management, identifying the root causes of the stress fracture, and modifying training or exercises to prevent a recurrence.

Do stress fractures ever fully heal?

Stress fractures are some of the most commonly occurring sports injuries. They are tiny breaks in the bone, usually caused by repetitive stress on the foot from activities like running. Although they can be quite painful, they usually heal themselves if you rest for a few weeks or months.

What are the 3 most important treatments for a fracture?

Treatment of bone fractures:

Depending on where the fracture is and how severe the injury occurs, treatment may include:

1. Splints – to stop the movement of the affected limb.

2. Braces – to support the bone.

3. Plaster cast – to provide support and immobilize the affected boneCan you make stress fractures worse?

If a stress fracture is not treated fully, the fracture may get worse or reoccur. It can heal improperly, leads to arthritis, or may even need surgery if not healed. Definitely do not ignore the pain, because ignoring the pain can lead to serious problems in the future, so it is important to see your doctor when you start feeling the pain in the fracture site.

Do stress fractures show up on MRI?

MRI Scans: An MRI scan can reveal a stress fracture up to two weeks before it is visible on an X-ray. MRI uses magnetic fields and radio waves to create 2 and 3-dimensional images of structures inside the body.