Anterior Cutaneous Nerve Entrapment Syndrome (ACNES)

Table of Contents

What is an Anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome?

Anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome (ACNES) is a condition characterized by chronic abdominal pain resulting from the entrapment of the anterior cutaneous branches of the lower thoracic intercostal nerves. This syndrome is often underdiagnosed, as its symptoms can mimic other more common abdominal or gastrointestinal conditions, leading to a delay in appropriate treatment.

Chronic pain in the abdomen wall that persists over time is most often caused by anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome. A diagnosis has been reported based on the patient’s history and physical examination. For the majority of patients, a local anesthetic injection—either alone or in combination with a long-acting corticosteroid—is beneficial and can support the diagnosis.

Due to the relative lack of knowledge about this condition, there is frequently a substantial delay in diagnosis and a high rate of misdiagnosis, which leads to needless diagnostic interventions and pointless operations.

Because the symptoms of ACNES are not unique to IBS, medical professionals can misidentify the illness as appendicitis or IBS.

Epidemiology

Abdominal wall pain is thought to affect 1 in 1800 people. Anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome was found in 2% of patients who visited the emergency room for examination of acute abdominal wall pain, according to retrospective research. Abdominal wall pain is found in 15–30% of patients with abdominal pain who had a negative previous diagnostic assessment.

Compared to men, women seem to be four times more prone to get anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome. Although occurrences have been observed in youngsters and older individuals, there have been two known peak incidences, between the ages of 15 to 20 and 35 to 45.

Etiopathogenesis

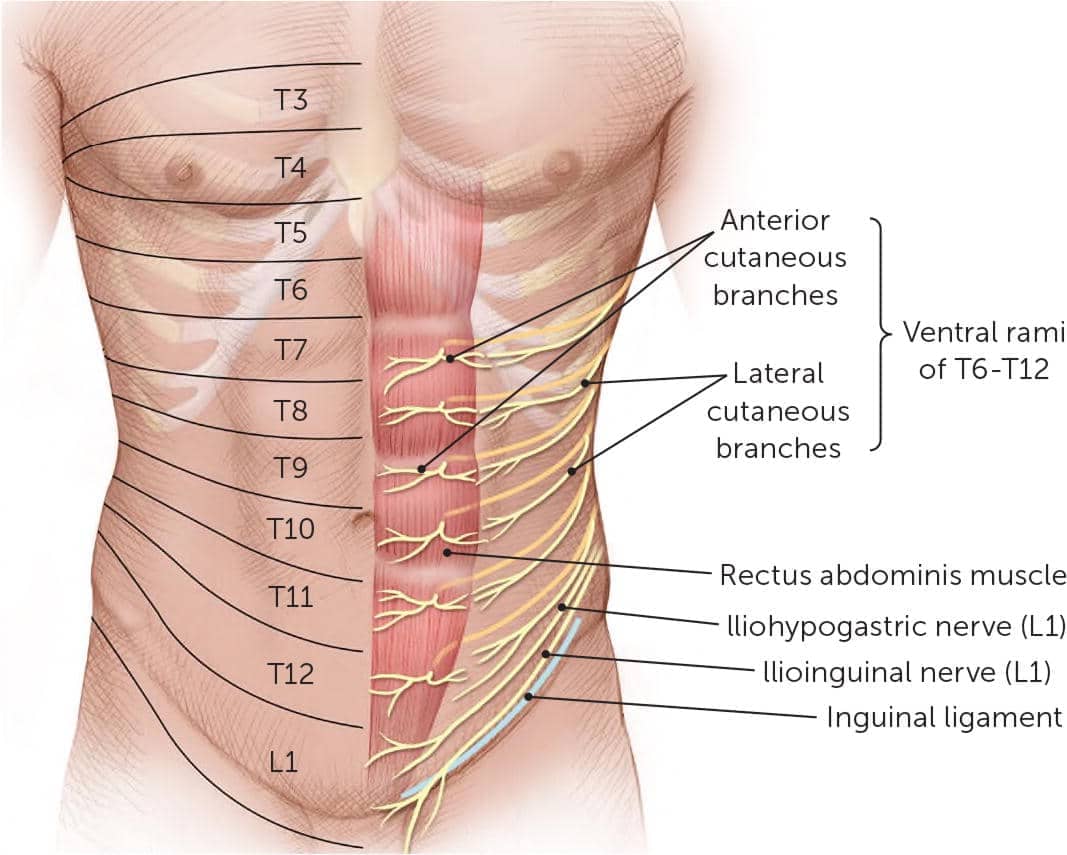

When the cutaneous branches of the sensory nerves feeding the abdomen wall become trapped, it results in anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome. As they advance anteriorly through the posterior rectus sheath and pass through a fibrous ring inside the lateral border of the rectus abdominis medial to the linea semilunaris, the cutaneous branches of the sensory nerves originating from T7 to T12 form a 90-degree angle. The nerves split at right angles once more beneath the skin, this time at the overlaying aponeurosis.

The neurovascular bundle’s fat normally allows the nerve to move freely inside the fibrous ring. Anterior Cutaneous Nerve Entrapment can result from a variety of conditions, such as intra-or extra-abdominal pressure, localized scarring, ischemia, and compression caused by the herniation of the fat pad that typically protects the nerve. In certain circumstances, additional mechanical factors including obesity and tight clothes may also be significant causes of nerve compression. Pregnancy and oral contraceptives have been linked to an increase in entrapment syndromes, maybe as a result of tissue edema caused by progesterone and estrogen.

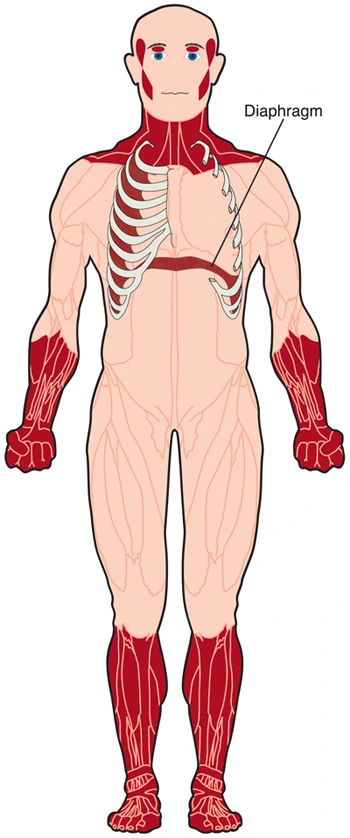

Usually, abdominal pain can be localized to a relatively particular location. The properties of the nerves that are producing the pain can account for this. A-delta and C nociceptors are the names of the two different kinds of pain receptors. Skin and muscle include A-delta nociceptors, which make up up to 25% of all nociceptors. They mediate sharp, rapid pain associated with injury, such as cuts, trauma, or pain in the abdominal wall. About half of all nociceptors are C-type nociceptors, which innervate the viscera, parietal peritoneum, and periosteum. They mediate the dull, hard-to-localize pain associated with intraperitoneal diseases.

Since localization is challenging for the majority of causes of intraabdominal pain, patients frequently wave their hands over a somewhat large area of the belly. On the other hand, the patient often uses one finger to indicate the position of A-delta nociceptors when the pain is in the abdominal wall.

Signs and Symptoms

Standard pain relievers usually only provide modest alleviation for affected persons, with the exception of certain neuroleptic medications. ‘Pseudovisceral’ phenomena, or symptoms of altered autonomic nervous system function, such as nausea, bloating, abdominal swelling, loss of appetite accompanied by a subsequent decrease in body weight, or changed defecation process, are often experienced by patients.

Movement can increase pain because it is usually caused by contracting the muscles of the abdominal wall. Often, the least painful stance is a quiet lie. The majority of patients say that they are unable to sleep on the uncomfortable side.

Diagnosis

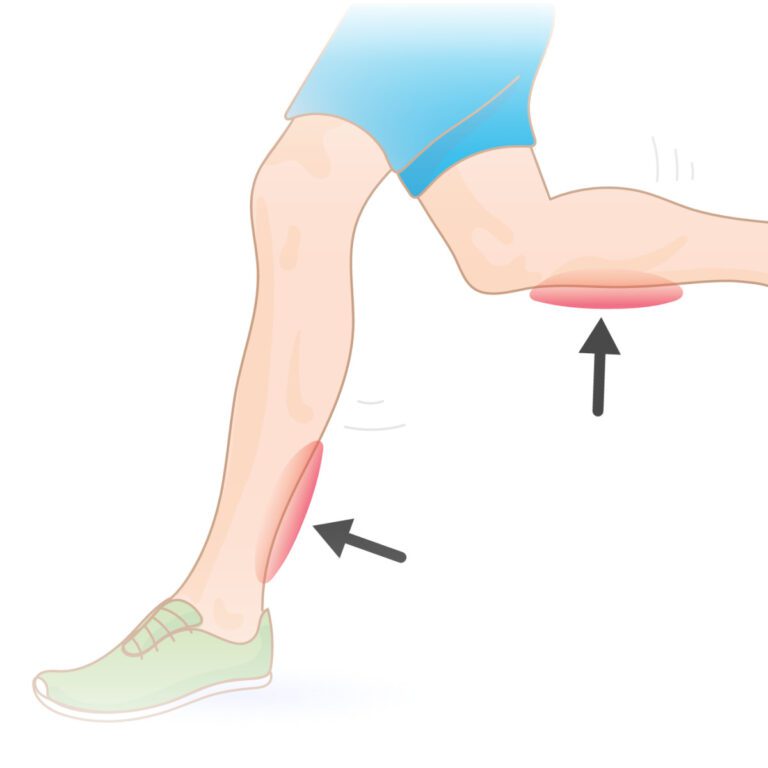

Carnett’s sign:

After taking the patient’s history into account, ACNES can be diagnosed with a comprehensive physical examination. This involves searching for a painful area that gets worse by tensing the abdominal muscles while raising the head and straightening the legs (a sign known as Carnett’s sign).

A broader area of changed skin responsiveness with somatosensory disturbances such as hypoesthesia, hyperesthesia, or hyperalgesia, and change in cold perception almost typically covers a small area of peak pain. Comparing the affected side to the non-affected side, pinching the skin between the thumb and index finger causes severe pain.

It is necessary to perform an abdominal wall infiltration with a local anesthetic agent close to the painful area in order to confirm the diagnosis of ACNES.

Treatment

Multiple such anesthetic injections are used as part of the treatment, occasionally in conjunction with corticosteroids. For two-thirds of patients, this kind of treatment results in long-lasting pain alleviation. This is a prospective double-blind trial that shows this favorable effect on pain. Additionally, the physical volume of the injection may disintegrate the fibrosis or adhesions causing the symptoms of entrapment.

Surgery may be recommended for patients who do not improve after receiving repeated local trigger point injections as a treatment plan. Anterior neurectomy refers to the removal of terminal branches of an intercostal nerve at the level of the rectus abdominal muscle’s anterior sheath. A further prospective double-blind surgical trial replicated the results of several bigger series, which showed a successful response in about two out of every three patients: 73% of patients who had a neurectomy experienced no pain, compared to 18% in the group that did not have their nerves removed.

Patients who do not respond to an anterior neurectomy or who (10%) experience a recurrence of pain syndrome following an initial period of painlessness may elect to have a second procedure. This involves a posterior neurectomy in addition to repetitive investigation. In 50% of cases, this technique has been demonstrated to be useful.

Managing the pain

When a patient exhibits any of the following symptoms—though not all of them must—a diagnosis can be made.

- Abdominal wall pain that is unilateral and lasts for at least a month

- An isolated painful spot at the abdominal wall (a fingertip trigger point situated at the lateral border of the rectus abdominis, measuring less than 2 cm2)

- Carnett’s test Positive

- At the site of the most severe pain, a positive skin pinch test and/or changed skin perception to light touch and/or cold

- Normal test results without any signs of infection or inflammation, and without any surgical explanation for pain

- abdominal wall imaging that is negative

- After administering a local anesthetic (often lidocaine) to the diagnostic trigger point, there is at least a 50% temporary improvement in pain responsiveness.

Painkillers, injections, and even surgery are used in a multidisciplinary manner to control pain.

Evidence/ Success

Big centers that perform ACNES operations report a 70% success rate after a year of good performance. Approximately two-thirds of patients do recover, experiencing an increase in their quality of life along with a decrease and, frequently, a complete stop to their pain medication.

Treatment Options

- Analgesics, such as morphine in certain situations

- Trigger point injections at the pain site

- ACNES surgery

Recovery and Rehabilitation

Make sure your treating clinician gives you sound rehabilitation guidance. If you have previously seen a physiotherapist, it may be worthwhile to continue receiving physiotherapy and rehab following your treatment.

Following trigger point injections, there may be some redness and a little increased pain; however, these side effects should subside in a few days or less. Before any effects are felt, the pain could get worse. Furthermore, following the treatment, the pain may return after it has subsided, sometimes lasting longer. This may occur a week or two afterward. No one’s ability to perform daily tasks is compromised by the process.

Surgery:

Painkillers are rarely needed after four days because the little scar heals after a few days of pain. It is possible for the wound to grow red, itchy, inflamed, and infected. If this happens, all that’s needed is a few days of antibiotics. It is also possible for the wound to leak fluid; in this case, a straightforward dry dressing is enough. In rare cases, the wound may fill with fluid; this is known as a seroma and goes away with pressure over time. If there is slight bleeding along with the seroma, it is known as a hemomatoma and very rarely requires reoperation.

References

- Anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome. (2024, June 1). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anterior_cutaneous_nerve_entrapment_syndrome

- UpToDate. (n.d.). UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/anterior-cutaneous-nerve-entrapment-syndrome

- Abdominal cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome (ACNES). (n.d.). https://www.manchestersurgicalclinic.com/conditions/abdominal-pain/acnes