Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS)

Table of Contents

Introduction:

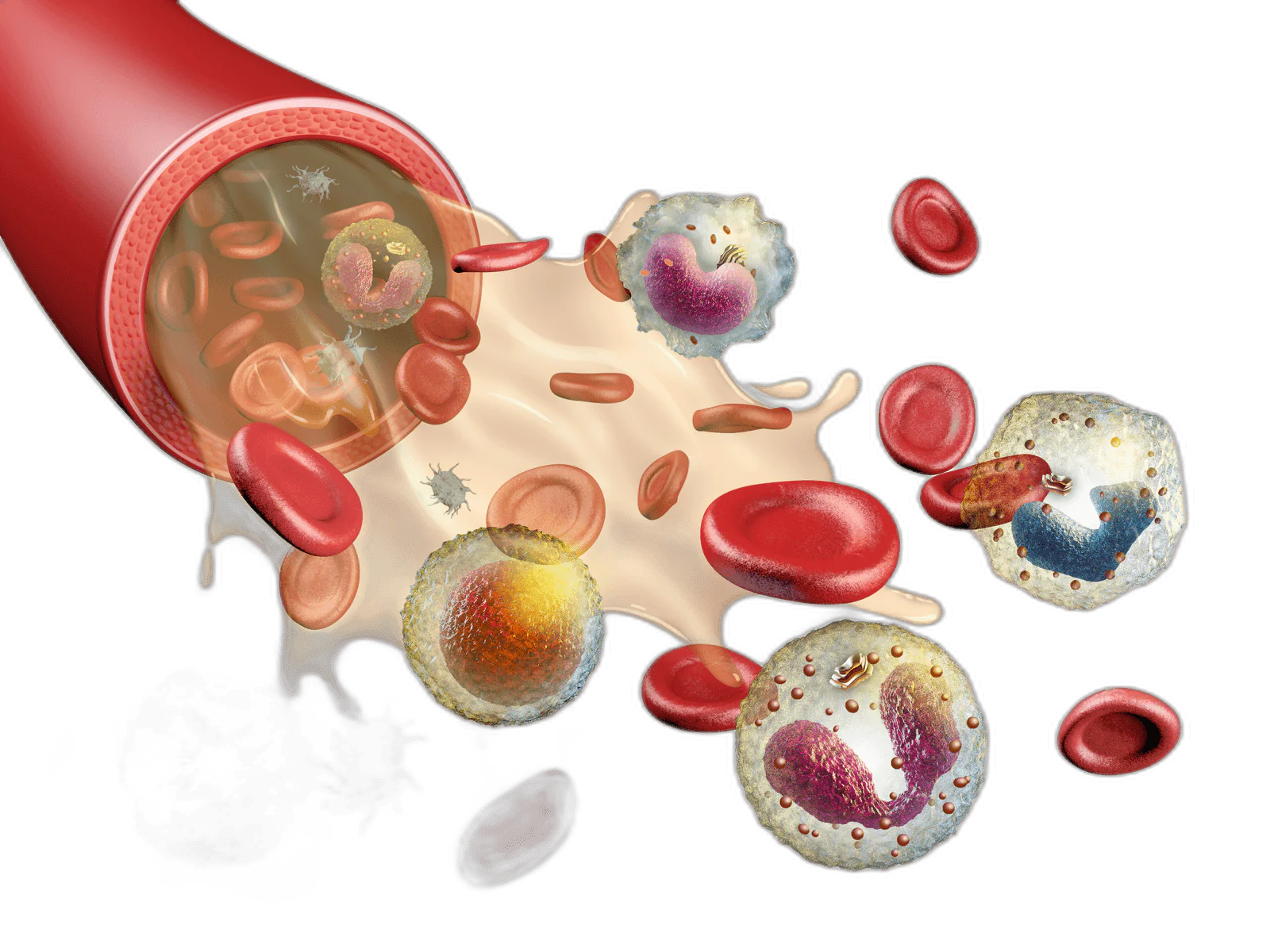

Autoantibodies that target phospholipid-binding proteins are known as antiphospholipid antibodies. A multisystemic autoimmune illness called antiphospholipid syndrome (APLS) exists. The presence of persistent antiphospholipid antibodies (APLA) in the presence of arterial and venous thrombus and/or pregnancy loss is the hallmark of APLS. The lower limbs and the cerebral arterial circulation, respectively, are the most frequent sites of venous and arterial thrombosis. Though it can happen in any organ, thrombosis can.

Antibodies that attack bodily tissues are accidentally produced by the immune system in the case of antiphospholipid syndrome. These antibodies may cause blood clots to form in veins and arteries.

Blood clots can develop in the legs, kidneys, lungs, and other organs like spleen. The clots can lead to heart attacks, strokes, and other conditions. Pregnancy-related antiphospholipid syndrome has the potential to result in stillbirth and miscarriage. Some persons with the condition display absolutely no symptoms.

Numerous drugs might lower the risk of miscarriage and blood clots despite the fact that there is no known solution for this uncommon illness.

What is Antiphospholipid Syndrome?

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), also known as Hughes syndrome or “sticky blood syndrome,” is an autoimmune disorder characterized by the presence of specific antibodies that target phospholipids, a type of fat molecule that plays a crucial role in blood clotting and other bodily processes. APS can lead to abnormal blood clot formation, which can affect various organs and systems in the body.

These antibodies greatly increase your risk of developing blood clots in your veins or arteries, miscarriages, and/or other pregnancy-related issues like preeclampsia.

An autoimmune condition known as antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS) primarily affects women between the ages of 30 and 40. Blood clots in veins and arteries can occur in APS due to aberrant proteins (aPL). Clots can injure a fetus, result in miscarriage, or cause heart attacks, strokes, or pulmonary embolism. Multiple organs may be injured in extreme situations. Antiphospholipid antibodies are found in about 40% of people with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), yet few of these people go on to develop clots.

An immune system illness called antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), also referred to as Hughes syndrome, raises the risk of blood clots.

This indicates that those who have APS are more likely to have conditions like:

DVT (deep vein thrombosis, a blood clot that typically forms in the leg)

Arterial thrombosis, which can result in a heart attack or stroke

Blood clots in the brain, which can cause issues with balance, mobility, vision, speech, and memory

Although the precise causes of this are unknown, pregnant women with APS are also more likely to miscarry.

APS doesn’t always result in obvious issues. Some people experience nonspecific symptoms, such as fatigue or numbness and tingling in several parts of the body, that can be comparable to those of multiple sclerosis (a common disorder affecting the central nervous system).

The laboratory tests used to diagnose APLA include functional assays and the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The three APLA are as follows:

IgG or IgM anticardiolipin antibodies (ELISA)

IgG or IgM anti-beta-2-glycoprotein-I antibodies (ELISA)

Anticoagulants for lupus (functional assays)

Causes of Antiphospholipid Syndrome

An autoimmune disorder, APS. This implies that the immune system, which typically defends the body from infection and disease, mistakenly assaults healthy tissue.

Antiphospholipid syndrome happens when the immune system mistakenly produces antibodies that raise the risk of blood clotting. Antibodies often protect the body from outside invaders like bacteria and viruses.

Antiphospholipid antibodies are aberrant antibodies made by the immune system in APS.

These substances target phospholipids, which are fat molecules connected to proteins, increasing the likelihood of blood clotting.

What triggers the immune system to create aberrant antibodies is unknown.

Genetic, hormonal, and environmental variables are thought to play a role, just like with other autoimmune diseases.

Antiphospholipid syndrome may be influenced by an underlying condition, such as an autoimmune disorder. The syndrome might also appear without any underlying cause.

Antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) in APS cause blood changes. They bind to proteins in lipids, which have an impact on the blood cells.

As a result, the cells clump together, which can obstruct blood flow through veins and arteries. Anywhere in the body, including the brain, can experience this.

These aberrant antiphospholipid antibodies in pregnant women can also harm the placenta and womb cells, decreasing blood supply to the developing child. This may stunt the child’s development and raise the possibility of miscarriage and stillbirth.

Pathogenesis:

“Antiphospholipid antibodies” (anticardiolipin antibodies and lupus anticoagulant) assault proteins that attach to anionic phospholipids on plasma membranes in the autoimmune condition known as antiphospholipid syndrome. It affects women more frequently than men, like many autoimmune diseases. Antiphospholipid syndrome affects women around five times more commonly than it affects men.

The syndrome is typically identified between the ages of 30 and 40. The coagulation system has obviously been activated, even though the particular method is unknown. Thrombosis and vascular disease are linked to clinically significant antiphospholipid antibodies (those that develop as a result of the autoimmune process). A syndrome can be classed as primary if there is no underlying disease condition or secondary if there is a relationship to an underlying disease state.

A subset of anti-cardiolipin antibodies and anti-ApoH bind to ApoH. apoH inhibits Protein C, a glycoprotein having a key role in regulating coagulation (inactivating Factor Va and Factor VIIIa). When lupus anticoagulant antibodies attach to prothrombin, it is more readily converted into thrombin, which is the active form.

Additionally, APS contains antibodies that bind to protein S, a co-factor of protein C. Protein C’s efficacy is therefore decreased by anti-protein S antibodies.

The creation of a barrier around negatively charged phospholipid molecules by annexin A5 reduces their availability for coagulation. Anti-annexin A5 antibodies thereby promote phospholipid-dependent coagulation events.

The lupus anticoagulant antibodies, which target 2glycoprotein 1, have a greater association with thrombosis than do antibodies that target prothrombin. Thrombosis is associated with anticardiolipin antibodies at moderate to high titres (above 40 GPLU or MPLU). The risk of thrombosis is increased in patients with moderate or high titre anticardiolipin antibodies in addition to lupus anticoagulant antibodies than in patients with only one of those antibodies.

Antiphospholipid antibodies are associated with an increased risk of recurrent miscarriage, intrauterine growth restriction, and preterm birth. This risk is supported by in vitro studies, which also show decreased trophoblast viability, syncytialization, and invasion, abnormal hormone and signaling molecule production by trophoblasts, and activation of the complement and coagulation pathways.

Classification of Antiphospholipid Syndrome

Primary or secondary antiphospholipid syndrome are both possible. Primary antiphospholipid syndrome is a disorder without any co-existing illnesses. Systemic lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune disorders are associated with secondary antiphospholipid syndrome. This condition, known as “catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome” (CAPS or Asherson syndrome), is rare and causes fast organ failure as a result of generalized thrombosis.

Antiphospholipid syndrome is routinely treated with anticoagulant drugs, such as heparin, to reduce the risk of future thrombotic episodes and enhance the prognosis for pregnancy. Contrary to heparin, warfarin (brand name Coumadin) is teratogenic and should not be used during pregnancy since it can pass through the placenta.

Signs and Symptoms of Antiphospholipid Syndrome

What manifestations of antiphospholipid syndrome are there?

Antiphospholipid Syndrome symptoms and warning indications can include:

- Clotting of the blood.

- Miscarriages that occur frequently (regularly).

- Having low levels of blood platelets.

- Having anemia, a lack of red blood cells.

- Having a reddish or purple pattern on your skin that resembles lace (livedo reticularis).

- Having defective cardiac valves.

- DVTs: are blood clots in the legs. Pain, swelling, and redness are symptoms of deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Pulmonary embolism is the result of these clots travelling to the lungs.

- Miscarriages or stillbirths: It keep happening. Other pregnancy dangers include premature birth and preeclampsia, which is abnormally high blood pressure.

- Stroke: A young person with antiphospholipid syndrome who has no recognized risk factors for cardiovascular illnesses may experience a stroke.

- TIA, or transient ischemic attack: A transient ischemic attack (TIA), like a stroke, typically lasts a short while and has no lasting effects.

- Rash: On some people, a red rash with a lacy, net-like look may develop.

- Blood clots are most frequently caused by antiphospholipid syndrome. Depending on where in your body the blood clot resides, different symptoms can be experienced.

Blood clot symptoms and warning signals can include:

- Shortness of breath and chest pain.

- You have discomfort, erythema, and swelling in your arm or leg.

- Headaches on a regular basis.

- You feel pain in your arms, back, neck, and/or jaw.

- Ache in the abdomen.

Less typical symptoms and indications include:

- Signs of the nervous system. Convulsions, dementia, and chronic headaches, including migraines, may occur when a blood clot blocks blood flow to certain regions of the brain.

- Circulatory system. Antiphospholipid syndrome may harm the heart valves.

- Thrombocytopenia, a low blood platelet count. Periods of bleeding, especially from the gums and nose, may result from this decrease in blood cells essential for clotting. Patches of tiny red spots will show up where bleeding has penetrated the skin.

Risk factors:

Women experience antiphospholipid syndrome more frequently than do males. People with lupus and antiphospholipid syndrome are more likely to have both conditions.

Antibodies associated with antiphospholipid syndrome may exist in the absence of any signs or symptoms. However, if you have these antibodies, blood clots are more likely to occur, particularly if you:

- Becoming pregnant

- are momentarily immobile, such as when undergoing bed rest or while seated on a long journey

- Undergo surgery

- Smoking

- Utilize estrogen treatment or oral contraceptives to treat menopause.H

- Have high levels of triglycerides and cholesterol

Complications

The antiphospholipid syndrome may cause the following complications:

Kidney disease. Reduced blood supply to your kidneys may cause this.

Stroke. A stroke can be brought on by reduced blood supply to a portion of the brain, which can lead to long-term neurological impairment such as partial paralysis and speech loss.

Heart and circulatory issues. The valves in the veins, which keep blood flowing to your heart, can be harmed by a blood clot in your leg. Your lower legs may become permanently discolored and swollen as a result. The possibility of cardiac damage is another risk.

Lung issues. These include pulmonary embolism and elevated blood pressure in the lungs.

Problems with pregnancy. These include preeclampsia, dangerously high blood pressure during pregnancy, preterm delivery, delayed fetal growth, stillbirths, and miscarriages.

Rarely, in severe cases, the antiphospholipid syndrome can quickly cause damage to several organs.

Diagnosis:

Multiple blood tests that look for antiphospholipid antibodies are used to identify antiphospholipid syndrome. Only those with blood clots and/or those who have recurrent (frequent) miscarriages typically undergo this test. Antiphospholipid antibodies are present in some individuals who never develop blood clots.

Three different blood tests must be performed in order to screen for antiphospholipid syndrome and look for antiphospholipid antibodies. Since no single test can detect every potential antibody, many tests are frequently used in tandem. To be diagnosed with antiphospholipid syndrome, at least one of the three types of blood tests must be favorable two separate times, each three months or more apart.

Despite having antiphospholipid antibodies, some persons never experience the syndrome’s symptoms or manifestations. You don’t necessarily have antiphospholipid syndrome just because you have the antibodies. You must have APS antibodies in addition to a history of APS-related health issues, such as blood clots and/or recurrent miscarriages, to be diagnosed with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS).

The presence of lupus anticoagulant, moderate-high titers of IgG or IgM anticardiolipin or anti-beta-2-glycoprotein I antibodies, or both, is necessary for the diagnosis of APLS in addition to the presence of clinical criteria. In order to exclude out clinically insignificant or temporary antibodies, the criteria further stipulate that a subsequent APLA test must turn up positive 12 weeks after the first positive test. If that interval is less than 12 weeks or if more than 5 years occur between two separate clinical symptoms and positive laboratory testing, the diagnosis of APLS is questionable.

Test for lupus anticoagulant

The biggest predictor of unfavorable pregnancy-related outcomes is the lupus anticoagulant test. When predicting thrombosis, it is less sensitive but more specific than anticardiolipin antibodies. 20% of patients with anticardiolipin antibodies also have a positive lupus anticoagulant test, and 80% of patients with a positive test also have anticardiolipin antibodies. The criteria for a diagnosis of APLS are not met by a false-positive syphilis test, although APLA should always be checked in individuals who have had prior thrombotic or unfavorable pregnancy-related events. A coagulation inhibitor of phospholipid-dependent coagulation events is present when a lupus anticoagulant is present. It does not directly interact with coagulation factors and is not linked to problems with bleeding. Patients who are taking heparin or warfarin may get false-positive and false-negative test findings.

A four-step test is used:

- Long-term phospholipid-dependent coagulation screening test (dilated Russell viper venom time or activated partial thromboplastin time)

- Despite combining the patient’s plasma with healthy, platelet-poor plasma, the prolonged screening test could not be fixed. This suggests the presence of an inhibitor.

- After the excess phospholipid was added, the prolonged screening test was corrected or improved. This suggests dependence on phospholipids.

- Excluding more inhibitors.

- Antibodies against beta-2-glycoprotein I and anti-cardiolipin

A typical method is the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), which is used to measure anticardiolipin antibodies and anti-beta-2-glycoprotein I antibodies. IgM and IgA antibodies don’t correspond as well with clinical symptoms as IgG antibodies do. Lower titers have a less well-established connection with thrombotic events than titers greater than 40 GPL units.

Additional Laboratory Results

In APLS, anemia or thrombocytopenia are frequently observed. Renal failure and proteinuria may suggest renal involvement with thrombotic microangiopathy. The acute thrombotic event may be accompanied by a high erythrocyte sedimentation rate. The rest of the time, inflammation-related indicators are often normal. Serologies that are specific to SLE, such as ANA, anti-Ds-DNA, anti-Smith, etc., may be positive in SLE patients. When present and associated with renal involvement, hypocomplementemia—which is uncommon in APLS—indicates lupus nephritis.

The presence of these antibodies alone does not establish a diagnosis of SLE in patients without any clinical signs of SLE. It is noteworthy that positive ANA and even anti-Ds-DNA is frequently detected in primary APLS without concomitant SLE. Testing for other hypercoagulable conditions, such as hyperhomocysteinemia, Factor V Leiden and prothrombin variants, shortage of protein C, protein S, or antithrombin III, may be necessary in a patient with multiple thrombotic episodes or pregnancy losses.

Classification Criteria

The Sapporo criteria, the original classification standards, were released in 1999 and were modified in 2006. At least one clinical and one laboratory criterion must be satisfied in order to meet the updated Sapporo categorization criteria for APLS.

Clinical Standards

For the purpose of diagnosing antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, one of the subsequent clinical symptoms should be verified.

Blood Thrombosis

- One or more instances of organ thrombosis in any of its arterial, venous, or tiny vessels. Using the proper imaging or histology, thrombosis must be conclusively proven. Thrombosis must be present for histopathology without a lot of vessel wall irritation.

- As long as a prior thrombotic episode was properly established by adequate diagnostic tools and there was no other cause of thrombosis, it can be used as a criterion.

- It is forbidden to use superficial venous thrombosis as a criterion.

Obstetric Morbidity:

- One or more fetal deaths of morphologically normal fetuses, as determined by ultrasound or physical examination, occur at or after 10 weeks of gestation.

- One or more morphologically healthy newborns who were born before the 34th week of pregnancy. Either severe preeclampsia, eclampsia, or placental insufficiency must have preceded the premature birth.

- After eliminating any anatomical or hormonal abnormalities in the mother as well as parental genetic reasons, there have been three or more consecutive spontaneous abortions before the 10th week of gestation.

Laboratory Standards

The antiphospholipid antibody syndrome should be identified based on one of the following laboratory results.

- Detection of Lupus anticoagulant in plasma found twice or more, each time at least 12 weeks apart.

- Detection of moderate to high titers of IgG or IgM anticardiolipin antibodies in serum or plasma, as determined by conventional ELISA on two or more times, spaced at least 12 weeks apart from each other (greater than 40 GPL or more than 99th percentile).

- Detection of moderate to high titers (greater than 99th percentile) of IgG or IgM anti-beta-2-glycoprotein I antibodies in serum or plasma, as determined by conventional ELISA, on two or more times, at least 12 weeks apart.

Treatment of Antiphospholipid Syndrome

Medical treatment:

Initial treatment for blood clots typically entails a mix of blood-thinning drugs. Warfarin (Jantoven) and heparin are the two most popular. Heparin is injected and has a quick onset of action. Warfarin is a medication that is taken orally and takes several days to work. Additionally a blood thinner, aspirin.

You run a higher risk of bleeding episodes if you take blood thinners. To ensure that your blood can clot sufficiently to stop the bleeding from a cut or the bleeding under the skin from a bruise, your doctor will monitor your dosage using blood tests.

The primary objective of treating antiphospholipid syndrome is to stop the occurrence of the illnesses it is causing, such as blood clots and/or miscarriages.

Blood clots are typically avoided by using blood thinners (anticoagulants). People with antiphospholipid syndrome may take these blood-thinning medications:

- Heparin, an anticoagulant, is administered intravenously (IV) to patients who have acute blood clots.

- Warfarin (Coumadin) taken orally: Taken as a tablet, this blood thinner helps prevent blood clots. Antiphospholipid syndrome patients frequently need to take an oral blood thinner for extended periods of time.

- Aspirin: Aspirin, which can help prevent blood clots, may be taken by people with antiphospholipid syndrome who have experienced a blood clot in an artery.

The following medicines can be taken by people with antiphospholipid syndrome who have had repeated miscarriages in order to avoid more miscarriages and have healthy pregnancies:

- Enoxaparin injections and low-dose aspirin are the recommended treatments for persons with antiphospholipid syndrome in order to prevent miscarriages. The combo therapy begins early in the pregnancy and is continued in the period right after the baby is delivered.

- IV immunoglobulin infusions: IV immunoglobulin infusions may be utilized in more challenging cases of recurrent miscarriage. Immune system diseases are treated with immunoglobulin infusions.

- Prednisone and prednisolone are two corticosteroids that may be administered in more complicated situations of recurrent miscarriage.

Some research suggests that additional medications may be effective in treating antiphospholipid syndrome. These include statins, rituximab (Rituxan), and hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil). More research is required.

Thrombosis Management

Primary thromboprophylaxis is questionable in patients with a positive blood test for APLA but no prior history of thrombotic events or pregnancy-related complications. Patients with SLE with positive APLA are particularly at risk for thrombotic events, and hydroxychloroquine, which has been demonstrated to be thromboprotective, is advised in these patients.

Aspirin taken at a low dose may also be an option. Low-dose aspirin may be recommended for prophylaxis for additional patients with APLA who have high-risk APLA profiles, such as triple positive with other thrombotic risk factors.

Long-term administration of warfarin with an INR target of 2.0 to 3.0 is advised for individuals who have experienced a venous thrombotic event. . It’s controversial whether a 2.0 to 3.0 INR target or a higher target of more than 3.0 should be employed for patients with arterial thrombosis. Patients who cannot tolerate warfarin or who do not respond to warfarin can be treated with low molecular weight heparin. The use of aspirin in addition to warfarin or high-intensity anticoagulation with warfarin with an INR objective of more than 3.0 can be considered in individuals who experience recurrent thrombosis despite receiving a sufficient dose of warfarin.

Randomized controlled trials have not demonstrated the efficacy of contemporary anticoagulant drugs as clopidogrel, aspirin-dipyridamole, argatroban, fondaparinux, dabigatran, etc. If there is an allergy to or sensitivity to warfarin, these medications can only be administered in APLS with one venous thrombotic agent. They are not advised in APLS, where using warfarin is possible, or in situations where venous or arterial thrombosis recurs often.

Gestational management

If you receive treatment, having an antiphospholipid syndrome pregnancy is still possible. Usually, heparin or heparin plus aspirin is given as a remedy. Pregnant women are not permitted to take warfarin since it can harm the fetus.

To guarantee the health of the fetus and prevent difficulties for the mother, all pregnant women with positive APLA results should be monitored throughout their pregnancies. The clinical situation determines the course of treatment for pregnant women with the goal of lowering the risk of unfavourable fetal outcomes.

Warfarin is teratogenic and should not be used during pregnancy, it must be mentioned. It is possible to utilize either low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or unfractionated heparin, however, LMWH is recommended due to its superior bioavailability, longer half-life, simple once-daily dose, and lower risk of thrombocytopenia and osteoporosis.

Pregnant women with a positive APLA test but no prior history of venous or arterial thrombosis:

- Initial pregnancy No therapy is recommended.

- Previous single-pregnancy losses with gestations under 10 weeks: No therapy is recommended.

- Multiple pregnancies that were lost when the gestation was under 10 weeks in the past: Throughout pregnancy, use low-dose aspirin together with prophylactic doses of unfractionated heparin or LMWH.

- A history of one or more pregnancies lost at more than ten weeks’ gestation: Throughout pregnancy, take low-dose aspirin together with LMWH or unfractionated heparin at a therapeutic dose. Heparin/LMWH can be stopped 6 to 12 weeks after delivery, and aspirin should be started before pregnancy.

- A positive APLA and a prior history of arterial or venous thrombosis in pregnant women:

- Throughout pregnancy, take low-dose aspirin together with LMWH or unfractionated heparin at a therapeutic dose. Following birth, these patients should switch to warfarin, which should be taken for the rest of their lives with an INR target of 2.0 to 3.0.

Management of Catastrophic Anti-Phospholipid Syndrome (CAPS)

The significant mortality rate linked with CAPS necessitates early diagnosis in order to effectively manage the condition. For CAPS management, there are no randomized controlled trials. IVIG, plasmapheresis, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, or eculizumab are utilized in conjunction with anticoagulation and high-dose corticosteroids.

Controlling Other Manifestations

Anticoagulation’s function in APLS’s other, non-criteria symptoms has not been proven. Treatment is not necessary for thrombocytopenia with a platelet count of greater than 50,000/mm3; If platelet counts are under 50,000/mm3, however, corticosteroids with or without IVIG or rituximab can be utilized. Additionally, splenectomy has been shown to be helpful for certain patients with severe thrombocytopenia that is refractory.

In order to rule out lupus nephritis, renal involvement with thrombotic microangiopathy must be established by a renal biopsy, especially in patients with concurrent SLE. For thrombotic microangiopathy, corticosteroids and anticoagulants might be administered. There is currently no known therapeutic treatment available for patients with heart valve nodules or malformations. Anticoagulation is advised, nevertheless, if there is evidence of an embolism or an intracardiac thrombus.

Multiple Diagnoses:

Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome-related thrombosis must be distinguished from other thrombosis-causing conditions such as hyperhomocysteinemia, factor V Leiden and prothrombin mutations, protein C, protein S, or antithrombin III deficiency.

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), vasculitis, hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), malignant hypertension, and lupus nephritis must be distinguished from APLS-associated nephropathy. In these situations, a kidney biopsy is frequently required for a diagnosis.

Prognosis:

Over a ten-year period, 90% to 94% of patients in several European studies survived. However, morbidity is substantial in APLS; at a 10-year follow-up, more than 30% of patients had irreversible organ damage, and more than 20% had severe impairment. CAPS, pulmonary hypertension, nephropathy, CNS involvement, and gangrene of the extremities are characteristics with a poor prognosis.

Overall, the prognosis for primary and secondary APLS is comparable, however, in the latter, any underlying rheumatic or autoimmune condition may worsen the morbidity. Antiphospholipid antibodies are associated with an increased incidence of neuropsychiatric problems in lupus patients.

FAQs:

An immune system illness called antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), also referred to as Hughes syndrome, raises the risk of blood clots. This means that those who have APS are more likely to get problems like deep vein thrombosis (DVT), a blood clot that typically occurs in the leg.

You will be given an antiplatelet drug, such as low-dose aspirin, or an anticoagulant drug, such as warfarin, as part of your treatment. These function by preventing the production of blood clots. As a result, blood clots that are unnecessary are less likely to form.

Despite the fact that there is presently no cure for APS, many individuals have extremely good prognoses, especially those who received prompt diagnosis and proper care. The ability of patients to feel in the future appears to be directly correlated with receiving an accurate diagnosis and treatment as soon as possible.

Antiphospholipid syndrome sufferers can typically have healthy lives if they take their prescribed medications and take care of their overall health. Antiphospholipid syndrome can be effectively treated and blood clots can be avoided using blood thinners.

Eat a healthy, balanced diet that includes lots of excellent carbohydrates, protein, low-fat dairy products, and lots of fruits and vegetables if you have APS. In order to lower your risk of cardiovascular problems like heart disease and to relieve pressure on your bones and joints, it’s crucial to maintain a healthy weight.