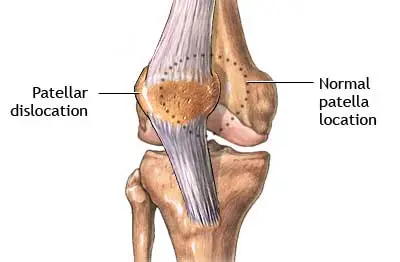

Patellar dislocation

Patellar dislocation, also known as a dislocated kneecap, occurs when the patella (kneecap) slips out of its normal position in the groove at the end of the femur (thigh bone).

This condition can cause pain, swelling, and instability in the knee joint. Patellar dislocation commonly occurs due to sudden changes in direction while running or jumping, direct trauma to the knee, or underlying anatomical factors.

Usually, it results following a forceful event such as a collision, a slip, or a poor step. A dislocated patella is uncomfortable and will make it difficult for you to walk, but it is simple to fix and occasionally corrects itself.

Table of Contents

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

A component of the knee joint is the patellofemoral joint. The patella and the trochlear surface of the femoral condyles make up the articular surfaces. The lateral facet is larger than the medial facet, and the articular cartilage on the lateral facet is thicker. On the side of the patellar groove, it has an anterior protrusion on the lateral femoral condyle. This stops the patella from dislocating to the side. The patellofemoral articulation depends on the quadriceps’ ability to work because it improves the angle at which the patellar tendon is pulled, enhancing the quadriceps’ mechanical advantage during knee extension

Passive and active stabilizers supply the patella with suspension and movement:

Passive stabilizer: Tensor fascia lata, the patellar ligament, the knee capsule, the patellofemoral ligament (medial and lateral), and the meniscal patellar ligament (medial and lateral) are examples of passive stabilizers.

Active stabilizer: Quadriceps, patellar ligament, and retinaculum are all active.

The principal stabilizer (53-67%) against lateral displacement or dislocation of the patella is the medial patellofemoral ligament. It is located deep within the vastus lateralis muscle, extending from the superomedial portion of the patella, vastus medialis, and the quadriceps tendon to the posterior region of the medial femoral condyle.

What is a patella (kneecap) dislocation?

Dislocations of the patella (kneecap) happen often, especially in younger athletes, and most of them happen laterally (outside). These are accompanied by severe pain and swelling when they occur. The first thing to do after a patellar dislocation is to move the kneecap into the trochlear groove. When someone extends their knee for an examination, whether it be on the field of play, in an emergency department, or a training room, this frequently occurs on its own. When relocation takes place before inspection, its occurrence must be addressed by identifying associated issues.

A patella dislocation occurs when the patella, the kneecap, slips out of its groove at the knee joint. Three bones — the thighbone, shinbone, and the kneecap in the middle — come together to form the knee joint. Normally, the kneecap moves up and down in a vertical groove between the end of the thigh bone and the ankle when you bend and straighten your leg and the trochlear groove at the top of the shinbone. The kneecap is held in place within the groove by a web of tendons and ligaments, which flex as it moves.

When the patella dislocates, it is ejected from the trochlear groove and is rendered immobile. This causes the knee to lock and tear ligaments from their normal positions. 93% of the time, the kneecap protrudes laterally, to the side of the groove. A patellar dislocation, which is often an acute injury, can happen as a result of a fast spin and twist or an impact. Similar to every dislocation, it hurts and limits motion until it is repaired. The kneecap, however, might occasionally realign itself.

In most cases, patellar dislocations are accompanied by complications, the most evident of which is the tearing of the ligaments that support the kneecap. The ligaments are ripped or disturbed, just like in all other joints, causing the joint to dislocate. The interior of the knee ligaments is more frequently hurt in a patellar dislocation because the kneecap moves laterally.

Although it is sad when these ligaments rip, they can sometimes mend. The little pieces of bone and cartilage that frequently fall off the kneecap or the lateral femoral condyle during the displacement of the kneecap are much more concerning. During arthroscopic surgery, these fragments typically need to be removed because they form loose bodies. Significant quadriceps muscle injuries can also result from patellar dislocations, which can be made worse by an effusion inside the knee, by starting activities too soon, or by rushing back into play.

Causes of Patellar Dislocation

A force, such as a direct hit or a poor step that uses your body weight against you, might result in an acute patellar dislocation. A severe fall or impact may dislocate the kneecap. It doesn’t always require that much, though. A straightforward pivot that twists the knee while the lower leg is still securely planted may be the culprit. This frequently happens to dancers and athletes who are prone to fast pivots

The tendons and ligaments that support the kneecap in place are already weak and unstable in certain patients due to patellar instability. This could be the result of an earlier injury or another underlying anatomical issue. An unstable kneecap will dislocate more quickly.

Trochlear dysplasia, often known as congenital patellar dislocation, is a birth defect. It frequently, though not always, has a connection to other developmental anomalies.

An injured kneecap may be brought on by:

- A knee injury, such as when the knee joint violently collides with another person or item.

- A swift turn while the leg is still firmly on the ground, as in dancing or athletic movements.

- Weak leg muscles put pressure on the knee joint.

- A kneecap that is crooked or high.

- Women are more susceptible to dislocation, and being tall and/or overweight enhances that risk.

The medial patellofemoral ligament may tear following a dislocated kneecap. The kneecap is attached to the inside (medial) of the knee using this ligament. It might not end with the same amount of stress after being torn. Recurrent kneecap dislocations may result from this.

Traumatic disruption of the previously unharmed medial peripatellar tissues is referred to as a primary patellar dislocation. It frequently follows a non-contact knee injury.

Both morphological and functional patellofemoral abnormalities are predisposing factors:

- Ligament flexibility (which may cause atraumatic dislocations)

- Lateral femoral condyle with decreased osseous constraint

- An imbalance between stronger lateral tissues and weaker medial structures, particularly the medial patellofemoral ligament and the distal vastus medialis, which can be overcome by the lateral retinaculum and vastus lateralis, among other stronger lateral tissues.

- The biomechanical issue includes femoral and tibial rotation, pes planus,

- Patella alta

- Genu recurvatum

- Q-Angle Increased

- Patellar Hypermobility

Mechanism of injury:

The injury mechanism is:

- A blow to the head that dislocates the patella

- Direct knee (lateral or medial) impact

- Knee or ankle flexion with internal femur rotation while standing on a stationary foot and tibia

- Frequently linked to valgus stress, which causes the patella to dislocate as a result of a significant lateral force

- Unplanned lateral cut

Who is impacted by Patellar Dislocation?

Anyone who sustains an injury can dislocate their patella. However, some individuals are more prone, such as:

- Notably, in high-impact sports, athletes.

- Dancers who frequently make sharp pivots.

- Teens, whose ligaments and joints are looser because of continuous growth.

- Women’s larger hips and looser ligaments cause the knee to experience more lateral stress.

- Big and tall men put additional strain on their joints.

- Those who have patellar instability, particularly if they have already had their patella dislocated.

While the exact cause of congenital patella dislocation is unknown, a higher occurrence within families raises the possibility of a hereditary component. It is also linked to a few other congenital diseases, like:

- Larson Syndrome.

- Arthrogryposis.

- Diastrophic Dysplasia.

- Nail-Patella Syndrome.

- Down Syndrome.

- Ellis-Van Creveld Syndrome.

Signs and symptoms of Patellar Dislocation:

Hemarthrosis of the knee, which is brought on by a rupture of the medial restraints of the patella, is one of the frequent symptoms associated with acute, primary, traumatic patellar dislocations. Additionally noticeable will be medial oedema. When the knee is stretched, patellar dislocations frequently spontaneously decrease.

The patient’s primary complaints will be:

- An audible pop.

- Buckling of the knee.

- Intense pain.

- Instability of the knee

- Sudden swelling.

- Bruising at the knee, along with excruciating knee discomfort.

- Locking of the knee.

- Inability to walk.

- Never attempt to move a dislocated kneecap on your own, as you risk doing more harm.

- A kneecap that is clearly distorted and may appear to be out of position or at an abnormal angle.

- Having trouble bending or straightening your leg

- Kneecap is visually out of place.

- Extreme discomfort at first till relocation happens.

- Ongoing discomfort in the medial (interior) ligaments.

- Medially at the location of ligament damage, and discolouration.

- A feeling of unease and worry that the issue will reoccur.

Differential Diagnosis:

- Osteochondral fractures

- Avulsion fractures

- Patellar fracture

- Patellar tendon tear

Diagnosis:

An experienced medical professional will physically examine your knee and ask you questions regarding the incident to determine whether you have a dislocated kneecap. However, they will request radiographic imaging tests to look for any associated wounds, such as fractures, torn ligaments, or cartilage damage. It is safe to fix the joint first and take photos after patellar dislocation.

You might not be aware that your patella was dislocated if it heals on its own. A “transient” dislocation is one that automatically corrects itself. Your knee will remain uncomfortable and swollen afterwards, and it may also resemble many other, more frequent knee ailments. Imaging investigations in this situation may reveal post-event indications of a dislocation along with any secondary injuries.

Physical examination:

The Patellar Apprehension Test, which involves rotating the patella back and forth as the person flexes the knee to around 30 degrees, can be used by a physician to evaluate the knee.

People can do the patella tracking evaluation while standing or while lying on their backs with their knees stretched from a flexed position. The J sign, which is a patella that slips laterally on early flexion, denotes an unbalance between the lateral and VMO structures.

Imaging:

X-rays; To rule out related fractures (osteochondral, avulsion); A lateral view will reveal subluxation

CT: The gap between the tuberosity and the trochlea groove

MRI: To distinguish between different types of tears and rule out osteochondral fractures

Recommended for young people with main dislocations

Dislocations are easily identified on an X-ray using skyline projections. The following metrics are useful in cases of subluxation on the edge:

- The most anterior points of the medial and lateral facets of the trochlea are connected by a line to produce the lateral patellofemoral angle.

- A deviation from the patella’s lateral facet.

- This angle ought to generally widen laterally with the knee bent at 20 degrees.

- The ratio of the medial joint space thickness to the lateral joint space (L) is known as the patellofemoral index. It should measure 1.6 or less with the knee bent at a 20° angle.

Treatment of Patellar Dislocation:

- Reduction: As soon as the diagnosis is certain, a skilled healthcare professional will manually realign the kneecap. It is referred to as a decrease. If there is a qualified healthcare professional around, they can start treating a patellar dislocation injury right away. If you visit the emergency room, sedatives and painkillers could be administered initially. The joint is often corrected first, and then they examine it on an X-ray.

- Imaging: Medical professionals will perform imaging tests to ensure that the kneecap has been replaced correctly and to determine whether any additional care is necessary. In addition to any additional injuries, X-rays and CT scans can assist identify any pre-existing anatomical problems that may have led to the dislocation. If necessary, an MRI can provide more precise information on the ligaments and cartilage. Sometimes a past transitory dislocation that wasn’t previously suspected is discovered by an MRI.

- Surgery: Your healthcare professional may advise surgery to repair any substantial damage to the knee’s bone, cartilage, or tendons. If you experience chronic patellar instability or recurring patellar dislocations, surgery can also be advised. The cartilage and ligaments can be repaired and strengthened as a prophylactic treatment to stabilize the knee. When patellar dislocation is congenital, surgery is the only way to restore the joint.

- Rehabilitation: For the first several days, you’ll be sent home with painkillers and a splint. Elevating and icing the joint on a regular basis can assist in reducing edema. You’ll gradually start using crutches and a brace to hold the joint in place as you walk again. To rebuild the muscles’ strength while limiting their range of motion until the joint has stabilized, physical therapy is crucial. A displaced patella requires between six and three months to fully heal.

Treatment method:

When a free fragment has not been formed, the standard treatment for patellar dislocations is to immobilize the knee for a brief length of time (seven to ten days). The swelling goes down during this period, and the acute discomfort from the dislocation also lessens. The patellofemoral joint and knee must be slowly mobilized during the healing phase, and full recovery is often anticipated after three to six weeks.

When the patellar dislocation occurs again, which is frequently anticipated when there is ligament hyperlaxity, this time frame is greatly lengthened. It is acceptable to handle these issues conservatively during the season by getting enough rest, strengthening the hip and thigh muscles, and possibly using a patellar buttress brace.

Hyaluronic acid, glucosamine, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are examples of alternative therapies.

Some patellar dislocation circumstances, such as those involving recurring dislocations, can and/or ought to be handled surgically. Patellar stabilization operations are necessary for these circumstances to prevent cartilage lesions on the undersurface of the patella, which are frequently irreparable, and to minimize the amount of time lost in the competition. These operations may involve soft tissue, bone, or a combination of both.

Retrospective investigations have shown that the likelihood of a subsequent dislocation after the initial one can reach 40%. This recurrence incidence could be decreased to under 10% by surgically correcting those dislocations by reducing lateral stress and strengthening medial restraint.

The majority of patella surgery is performed in an outpatient environment. A return to exercise can be anticipated as early as six weeks after procedures that are confined to changing soft-tissue tension. Osteotomies, which entail bone treatment, necessitate a period of relative immobilization and take 10 to 12 weeks before a patient is allowed to resume physical activity.

Medical Treatment

Conservative Management

Indication:

- A primary dislocation of the patella

- If the patella does not move on its own, it can be moved under regional anaesthetic. Following a reduction, conservative management entails the following:

- (Cylindrical cast, back slab, knee range of motion brace) 6-week immobilization

- Medication: Glucosamine supplements and NSAIDs

After the first patellar dislocation, conservative therapy is most frequently used.

Surgical treatment:

Arthroscopic surgery is used for surgical care, either with or without immediate patellar realignment or surgical repair of the torn retinaculum.

Indications:

- Chronic or recurrent dislocation

- Signs of patellofemoral pain

- Severe chondral damage or an associated osteochondral fracture

- Significant rupture of the vastus medialis obliquus-adductor mechanism and the medial patellofemoral ligament

- On the plain Mercer-Mercantile view, the lateral patella is subluxated, while the contralateral knee is aligned normally.

- Conservative management went wrong

- In the population of young adults, surgical stabilization greatly lowers the redislocation rate of primary traumatic patellar dislocation but is linked to a higher incidence of osteoarthritis of the patellofemoral joint. Cryotherapy, physiotherapy, and pain management make up the initial post-operative care.

Types of Surgery

- Lateral release:

In order to enhance the patella’s medial tracking, the lateral retinaculum must be released.

Indication: Mild patellar instability is a sign.

- Reconstruction of the medial patellofemoral ligament and proximal realignment:

Patellar tracking should be balanced for better natural (medial) alignment.

Frequently performed with a lateral release

Indication: extremely unstable patella

- Realignment/anteromedialization at the distal end:

Transferring the tibial tubercle (the area of the tibia to which the patellar tendon is attached). To enable the patella to track normally, the bony connection of the tendon is relocated more medially.

Used in conjunction with the medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction and/or the lateral release.

Indication: extremely unstable patella

Physiotherapy Treatment in Patellar Dislocation

Goals:

- Improve performance

- Avert more dislocation:

- Taping: Lateral reinforcement will limit patella mobility (preventing dislocation).

Physiotherapy techniques consist of:

- Re-dislocation prevention:

Taping: Lateral support will limit patella movement (preventing dislocation).

Bracing

Confidence-building and behaviour modification - Increased Range of motion(ROM):

Knee manual treatment

Kneading Mobilization exercises

Combining therapy - Strengthening Exercise:

- Quadriceps, hamstrings, hip external rotators, adductors, hip, and lower abdomen strengthening exercises

- Exercises such as:

- Leg dips with internal tibial rotation

- Side-lying clam shells

- Isometric quadriceps sets

- Exercises with a closed kinetic chain are advised

- The theory is that medial strengthening will give more stabilizing support because the medial side is most frequently stretched by the more frequent lateral dislocation. Exercises that need a greater range of motion are added as you advance.

- Stretching:

Increase hamstring and quadriceps flexibility

- Proprioception: Increase knee stability

How to Prevent Patellar Dislocation?

All dislocations, to some extent, stretch the ligaments and damage the joint cartilage. If your patella is similarly wounded after a previous dislocation, it is more likely to occur again. Although accidents are difficult to avoid, there are occasionally contributing factors that we may try to lessen. Depending on what initially caused your patella to dislocate, you might wish to follow one or more of these preventative measures:

- Responsible rehabilitation. The most crucial step you can take to prevent a further patella dislocation is to fully recover from your initial one. That entails completing physical treatment as directed and taking care to avoid using the leg too vigorously too soon. Give it the time and care it requires to heal as effectively as possible.

- Conditioning of the legs: It may be ensured that no muscle group is overworked by gradually strengthening each of the many muscle groups that stabilize the knee. Stretching is essential to ensuring that every muscle group has the full range of motion it should. You can get started on the correct path for a lifetime of practice with the aid of a physical therapist or personal trainer.

- Proper form for sports: If you’re an athlete, you might wish to have a professional check your form during specific workouts and movements you practice. Your muscles and joints may experience recurrent stress if you practice with poor form.

- Surgery: If your anatomy makes your patellar instability more likely, you might think about having surgery to strengthen your knee. If you want to know if you are a suitable candidate for reconstructive surgery, talk to your doctor.

Prognosis:

Your prognosis is good if you have had treatment for a first-time patella dislocation injury. The majority of people will totally recover in six weeks. Long-term issues can lead to osteoarthritis later in life by causing the cartilage to degenerate and making the knee joint less stable.

If you experience recurrent patellar dislocations or chronic patellar instability, surgery to help stabilize the joint can be a good option for you. Although surgery has a high success rate for stability, osteoarthritis is a long-term side effects.

Although painful and frightening, a displaced patella is not as dangerous as other dislocation injuries. Since the patella can be dislocated with less force than other bones, there is a lower chance that nearby blood vessels or nerves will sustain harm. Additionally, it moves more quickly and occasionally by itself.

The first concern after dislocating your kneecap is getting it back in place. You or a qualified expert might be able to solve it right away. If not, your doctor can do it for you and give you painkillers to make it less uncomfortable. After that, you should be back on your knee in approximately six weeks with some rest and therapy.

Summary:

Patellar dislocation, also known as a dislocated kneecap, occurs when the kneecap slips out of its normal position. It can cause pain, swelling, and instability. It is often due to sudden changes in direction, trauma, or anatomical factors. Diagnosis involves a physical examination and imaging tests.

Treatment options include nonsurgical approaches like rest, immobilization, pain medication, and physical therapy, as well as surgical options for more severe cases.

Rehabilitation plays a crucial role in recovery. Preventive measures include strengthening thigh muscles, using proper techniques during physical activities, and avoiding excessive stress on the knees. Consulting with a healthcare professional is important for an accurate diagnosis and treatment plan.

FAQs:

What is the most common cause of patellar dislocation?

A direct impact to the medial aspect of the knee or a non-contact twisting injury to the knee are the two most common causes of acute patellar dislocations. External tibial rotation with the foot locked to the ground is a typical mechanism.

Can you fully recover from patellar dislocation?

Your prognosis is good if you have had treatment for a first-time patella dislocation injury. The majority of people will totally recover in six weeks. Long-term issues can lead to osteoarthritis later in life by causing the cartilage to degenerate and making the knee joint less stable.

Can you run after knee dislocation?

Children and teenagers must refrain from sports and other physical activity for a few weeks after dislocating a kneecap.

Is surgery necessary for dislocated patella?

If you have dislocated your kneecap for the first time, conservative treatment is usually employed. Surgery is typically recommended if it occurs a second time or repeatedly.

What is the success rate of patellar dislocation surgery?

Small incisions are used during the treatment, which is referred to as an MPFL reconstruction. This surgery has a success rate of 95+% in avoiding future dislocations when performed by a qualified professional.

One Comment