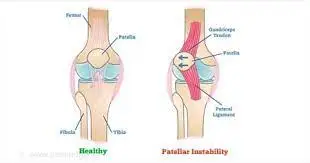

Patellar Instability:

Table of Contents

What is patellar instability?

Patellar instability means an unstable kneecap(Patella Bone). It occurs when the kneecap moves out of the groove(trochlear groove) at the end of the femur (thighbone). When you bend and straighten your knee from the joint, at a time the kneecap also moves up and down in a notch called the trochlear groove.

Anatomy:

The patella (kneecap) connects to the femur (thigh bone) and tibia (shin bone) by tendons. The patella fits into a groove at the end of the femur called a trochlear groove and slides up and down as the knee bends and straightens.

Definition:

Patellar instability occurs when the kneecap moves outside of this groove at the end of the femur that holds the patella in its place.

Patellar instability is a condition where the patella bone pathologically nonarticulates out from the patellofemoral joint(joint between patellar bone and femur bone), it occurs either by subluxation or complete dislocation.

Patellar instability means when the patella (kneecap) slips out of the trochlear groove of the femur in the thighbone. An unstable patella can lead to a dislocated knee. Physical therapy and leg braces can help to stabilize it. Some people have chronic (ongoing) patellar instability. This condition rises the risk of dislocated knees, ACL tears, and arthritis in the knee.

There are two types of patellar instability:

- Traumatic dislocation

- Chronic patellar instability or subluxation

The first is called a traumatic patellar dislocation. This most often occurs due to the result of an injury to the knee. The patella gets entirely pushed out of the groove in a patellar dislocation.

Patellar instability can lead to a dislocated kneecap. So, dislocation is of two types:

- Complete dislocation: The ligaments that hold the patella in place slide to the outside of the knee, taking the kneecap with them. The ligaments can tear or stretch. The patella is completely out of place.

- A partial dislocation (subluxation): The patella slips partly out of the groove.

The other type of patellar instability is called chronic patellar instability. The patella usually only slides partly out of the groove in this type. This is called a subluxation.

Causes of Patellar Instability:

The patella is part of the skeletal system. Connective tissues (muscles, tendons, and ligaments) present in the front of the thighbone (femur) go over the patella and connect to the shinbone (tibia). These muscles pull the kneecap up through the trochlear groove when the person straightens their leg and down the groove when they bend it. When the kneecap is not stable, it moves outside of this groove.

Causes of patellar instability:

- Shallow or uneven trochlear groove.

- Loose ligaments or extremely flexible joints.

- A sharp blow to the kneecap during a fall, sports injury, or other accident.

There are two ways to develop patellofemoral instability dislocation of the patella.

- It can occur after traumatic dislocation of the kneecap in which the medial kneecap stabilizers are stretched or ruptured, which eventually can result in recurrent dislocations of the patella.

- Another way is caused by an anatomical abnormality of the knee joint.

Chronic instability of the patellofemoral joint and recurrent dislocation may direct to progressive cartilage damage and severe arthritis if it is not treated adequately

Patella dislocation after trauma:

Acute traumatic patellar dislocation accounts for around 3% of all knee injuries. The ultimate mechanism of acute dislocation of the patella is knee flexion with internal rotation on a planted foot(foot downward) with a valgus component. This mechanism accounts for 93% of all cases. One of the common determinations related to acute, primary, traumatic patellar dislocations is hemarthrosis of the knee, caused by a break of the medial ligamentous stabilizers of the patella. This leads to bleeding into joint spaces, resulting in swelling and the formation of bruises around the kneecap. Knee joint effusion is also a typical symptom after a patellar dislocation. This can provoke severe pain and it may restrict the clinical examination.

Traumatic kneecap dislocation is generally the result of a sports injury and about two-thirds of the cases occur in young, active patients under the age of 20. In case of traumatic dislocation, conservative management may be selected. Subjects may even produce patellar instability, (aspecific) pain, patellofemoral arthritis, or even chronic patellofemoral instability, based on the presence and severity of the anatomic damage.

Patella dislocation with a precise functional or anatomical cause:

Dislocations without acute knee hemarthrosis, which are mainly recurrent dislocations, may be associated with abnormalities of the patellofemoral joint.

These anomalies concern Trochlear dysplasia, Patella alta, and Lateralization of the tibial tuberosity (excessive lateral distance or gap between the tibial tubercle and the trochlear groove). These all are the direct causes of dislocations with anatomical reasons.

- Significant secondary factors contributing to patellofemoral instability are

- Femorotibial malrotation

- Genu recurvatum (hyperextended knee)

- Ligamentous laxity induced by Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and

- Marfan syndrome.

Signs and Symptoms of Patellar Instability:

Patients experience anterior knee pain and episodes of mechanical instability. The pain can be exacerbated by activities such as climbing stairs up and down, sports such as running, hopping and jumping, and changing direction. Upon functional assessment the patient may struggle with control of the patella, resulting in the patella being pulled from the midline, therefore to assess this you need to observe what is occurring to the patella during stationary and dynamic movements such as squatting/lunging.

A person may experience symptoms such as pain, swelling, stiffness, difficulty walking on the affected limb, and/or buckling, catching, or locking sensation in the knee. Lastly, there may also be a noticeable deformity in the affected knee compared to the nonaffected knee.

Most patients feel a sensation that the patella has shifted or moved out of place. Generally, the patella will move back in on its own but sometimes it will need to be put back in place in the Emergency Room.

With chronic patellar subluxations, the pain may be less severe compared to the pain in a traumatic injury.

Patients may complain of pain below the kneecap, especially with activities that involve deep or more knee bending.

- Knee buckles and can no longer support the weight

- Kneecap slips off to the side

- Knee catches during movement

- Pain in the anterior side of the knee that increases with activity

- Pain when sitting

- Stiffness

- Creaking or cracking sounds during movement

- Swelling

- Cracking or popping sounds in the knee when they climb stairs or bend the knee.

- Feeling like the patella is catching on tissue or moving from side to side.

When the kneecap slips out of the trochlear groove, the knee may buckle. A knee and leg may not be able to support the weight or keep a person standing upright. A person can not be able to straighten the knee or walk.

Risk Factors:

- Anyone can develop patellar instability. Females tend to have looser ligaments that make females more inclined to patellar instability.

- A person may have a higher risk if they play high-impact sports like football or do activities that require a lot of quick pivoting, like basketball, cheer, or soccer.

- Certain health conditions can provoke loose connective tissue that contributes to patellar instability. These may include:

- Cerebral palsy.

- Down syndrome.

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Other Risk factors :

- Insufficient deep articular surface (trochlea dysplasia)

- Insufficient distance or gap between tibial tuberosity and the trochlear quarry

- Insufficiency of the Medial Patellofemoral Ligament

- Patella alta (engagement into the trochlea does not occur in the early phase of knee flexion, thus potentiating instability occurs at the patellofemoral joint)

- Knee valgus: An increased Q-angle may affect the patella tracking in the knee joint

- Inadequate VMO

- A lesion of the medial retinaculum

General factors :

- Ligamentous laxity (Ehlers-Danlos syndrome)

- Previous patellar instability event

- “Miserable Malalignment Syndrome”

- It is a term called for the 3 anatomic characteristics that direct to an increased Q angle

- Femoral anteversion

- Genu valgum

- External tibial torsion / pronated feet

Anatomical factors:

- Osseous:-

Patella alta: In this, causes the patella not to articulate with the sulcus, losing its constraint effects

Trochlear dysplasia

Excessive lateral patellar tilt (measured in extension)

Lateral femoral condyle hypoplasia - Muscle:-

Dysplastic vastus medialis oblique (VMO) muscle

Overpull of lateral structures

Iliotibial band

Vastus lateralis

Evaluation:

Presentation:

- Patient age and gender

– More likely in females

– More likely to occur in younger age groups (10-17 years old)

- Record the number of previous dislocation or subluxation events in the patella

- Complaints of patellar instability

- History of general ligamentous laxity in the patella

- Any previous surgery on the knee

- Pain location

– Anterior knee pain

Physical Examination: The examination will evaluate several areas.

- Evaluate overall limb alignment

- Hip and knee rotation should be noted

- Excessive or more femoral anteversion will show the patient’s toes pointed in or “pigeon-toed”

- Presence of large hemarthrosis

- Proof of an acute injury

- The absence of signs of trauma keeps a chronic ligamentous laxity mechanism or a habitual mechanism

- Tenderness on the medial-sided over the medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL)

- Increase or more in passive patellar translation compared to the contralateral side

- Midline is considered the ‘0’ quadrant of movement

- Normal is < 2 (less than 2) quadrants of patellar translation

- Lateral translation of the medial border of the patella to the lateral border of the trochlea is ‘2’ quadrants of motion and considered abnormal

- Apprehension sign:- Patella apprehension with passive lateral translation results in guarding and the absence of a firm endpoint

- J sign:- More than normal lateral translation in extension, which then causes the patella to “pop” into the trochlear groove as the patella engages the trochlea early in flexion.

- Assess the Q-angle

- Q-angle is the angle formed by a line from the ASIS to the center of the patella and from the center of the patella to the tibial tubercle

- The Q-angle in full extension can be falsely normal because the patella is not fixed in the trochlea and not on tension. Therefore it is suggested to assess the Q-angle in slight flexion, which is more reliable and accurate.

Diagnosis:

Radiograph

Rule out fractures or loose body

- Medial patellar facet (most common)

- Lateral femoral condyle

1. AP views

- Most useful to evaluate overall lower extremity alignment and version

2. Lateral views

Best to assess for trochlear dysplasia

- Crossing sign

- The trochlear groove is situated in the same plane as the anterior border of the lateral condyle

- Represents flattened trochlear groove

- Double contour sign

- The anterior border of the lateral condyle is situated anterior to the anterior border of the medial condyle

- Represents convex trochlear groove/hypoplastic medial condyle

- Supratrochlear spur

- Arises in the proximal aspect of the trochlea

Assess for patellar height (patella alta vs. Baja)

- Blumensaat’s line should extend to the Inferior pole of the Patella at 30 degrees of knee flexion

- Insal-Salvati method

- Normal between 0.8 and 1.2

- Blackburne-Peel method

- Normal between 0.5 and 1.0

- Caton Deschamps method

- Normal between 0.6 and 1.3

- Plateau-patella angle

- Normal between 20 and 30 degrees

- Sunrise/Merchant views

- It’s good to assess for lateral patellar tilt

- Lateral patellofemoral angle (normally is an angle that opens laterally)

- The angle between the line along the subchondral bone of the lateral trochlear facet + posterior femoral condyles

- Normal > 11°

- Congruence angle (normal is -6 degrees)

- Sulcus angle

- Evaluate for trochlear dysplasia

- Values > 140 degrees indicate flattening of the trochlea concerning dysplasia

CT scan

- TT-TG distance

- Take perfect measurement of the distance between 2 perpendicular lines from the posterior cortex to the tibial tubercle and the trochlear groove.

- 20mm is usually considered abnormal

MRI

- Help in further ruling\ out suspected loose bodies

- Osteochondral lesion and bone bruising

- Medial patellar facet (most common)

- Lateral femoral condyle

- Tear of MPFL

- Usually, a tear at the medial femoral epicondyle

Treatment of Patellar Instability:

After an acute first-time patellar dislocation, a conservative treatment method is indicated. Coronal, sagittal, and axial views are performed to first assess the presence of patellar or condylar fractures and then to examine anatomic risk factors. MRI images are indicated in emergency only in skeletally immature patients ruling out osteochondral fractures, which set an immediate surgery

First-time patellar dislocation occurs due to Lipohemarthrosis, MPFL rupture, and Bone bruise. Remember to search for osteochondral fractures also

No immobilization is needed in order to avoid knee stiffness. A light brace and/or crutches might be used to reduce pain during the first week.

In case of severe and painful lipo hemarthrosis, an arthrocentesis might be considered to aspirate the intra-articular liquid and reduce the pain caused by the increased pressure.

Adult treatment:

Nonoperative methods:

NSAIDS, activity modification, and physical therapy

Indications:

- The mainstay of remedy for first-time patellar dislocator

- Without any loose bodies or intraarticular damage

- Habitual dislocator

Techniques:

- Short-term immobilization for ease followed by 6 weeks of controlled motion

- Emphasis on strengthening

- Closed chain short arc quadriceps exercises

- Quad strengthening

- Core and hip strengthening to enhance limb positioning and balance (hip abductors, gluteals, and abdominals).

- Patellar stabilizing sleeve or “J” brace

- Consider knee aspiration for tense effusion

- Positive fat globules indicate the fracture

Operative Methods:

Arthroscopic debridement (removal of the loose body) vs Repair with or without stabilization

Indications:

- Displaced osteochondral fractures or loose bodies

- This may be an indication for operative treatment in a first-time dislocator

Techniques:

- Arthroscopic vs open removal versus repairing of the osteochondral fragment

- Primary repair with screws or pins if adequate bone available for fixation

MPFL repair

Indications:

- Acute first-time dislocation with bony fragment

Techniques:

- Direct repair when surgery can be done within the first few days

- No clinical studies support this over nonoperative treatment

MPFL reconstruction with autograft vs allograft

Indications:

- Recurrent instability

- No significant underlying malalignment

Techniques:

- Gracilis or semitendinosus muscle commonly used (stronger than native MPFL)

- Femoral origin can be reliably seen radiographically (Schottle point)

- a femoral tunnel positioned too proximally results in a graft that is too tight (“high and tight”)

Outcomes:

- Extreme trochlear dysplasia is the most important predictor of residual patellofemoral Instability after isolated MPFL reconstruction

- The rate of recurrent instability does not differ with regard to graft choice (allograft vs. autograft vs. synthetic graft)

Fulkerson-type osteotomy method (Anterior and Medial tibial tubercle transfer)

Indications:

- May be used in addition to MPFL or in isolation for meaningful malalignment

- TT-TG >20mm on CT

Techniques:

- Anteromedialized displacement of osteotomy and fixation

- Patellofemoral contact pressures increased proximally and medially

- Correct TT-TG distance to 10-15mm (never less than 10mm)

Tibial tubercle distalization

Indications:

- Patella alta

Techniques:

- Distal displacement of osteotomy and fixation

Lateral release

Indications:

- The isolated release is no longer indicated for instability

- Only indicated if there is extreme lateral tilt or tightness after medialization

Techniques:

- Arthroscopic

Trochleoplasty

Indications:

- Rarely handled even if trochlear dysplasia present

- May consider in severe or revised cases

Techniques

- Arthroscopic or open trochlear deepening procedure

Pediatric Treatment

- Same principles as adults in general but

- Must preserve the physis

- Not to do tibial tubercle osteotomy (will harm the growth plate of the proximal tibia)

Physical therapy treatment in Patellar Instability:

The rehabilitation program has a goal to restore a complete range of motion, increase the strength of the quadriceps and stretch the knee lateral compartment soft tissues, and finally guide the medial side healing.

Several authors have suggested surgical treatment after a first-time patellar dislocation, consisting of acute repair or reconstruction of the torn MPFL. Debated occurs on whether the surgery leads to better clinical outcomes and reduced risk of re-dislocation than conservative management. Currently, expert consensus recommends a conservative treatment after a first-time dislocation.

The patient is visited at 45 days to evaluate the anatomic risk factors, give a prognosis on the recurrence rate, and explain to the patient what could be the future.

Nonsurgical treatment after Acute Patellar Dislocation

After a first dislocation, there is a need for conservative or surgical treatment. In both treatment methods, there is a requirement for immobilization. There are several options for immobilization: a cylinder cast, a posterior splint, a brace, or tape.

The period of immobilization may change from no immobilization to six weeks. The optimal duration has not been determined yet. Mostly 2-3 weeks of immobilization are applied. It is most crucial to keep the immobilization period as short as possible since immobilization may have some injurious effects on ligament strength, and joint cartilage and may cause prolonged weakness of the bony origin of ligaments. This might result in muscular atrophy, flexion deficit, and potentially poor (short-term) functional result. Therefore rehabilitation must be started as soon as possible.

The aim of rehabilitation is to restore the knee’s range of motion and improve patellar stability by reinforcing the quadriceps.

Early mobilization begins with closed-chain exercises and passive mobilization.

In the acute term, Exercises are:

- Quadriceps setting exercises: Isometric knee exercise. Supine position, ask the patient to squeeze the knee or to press a towel under the knee and hold for 5 sec and then release.

- Three sets of 15 to 20 times straight leg raise (SLR): In the supine position, keep the unaffected leg flexed and do straight leg raise with the affected leg.

Done 4-5 times a day.

ICE: Ice is applied for 15-20 minutes every two to three hours to lessen swelling.

Some examples of closed-chain exercises are:

- Wall sets (the patient squats until approximately 40° while keeping his back flat to the wall for 15 to 20 seconds, for a total of 10-15 repetitions)

- Side and Forward step-up exercises

- Short arc leg presses.

- Stationary bike.

- Stepping machine exercises.

There has been a lot of study on whether the focus should be on the VMO, but there is no evidence that this would seriously enhance patellar stability.

Stretching: Besides training the quadriceps muscle, stretching of the Hamstring muscle and articular retinaculum should be contained in the rehabilitation program one month after the trauma. Patient education should be part of the therapy or treatment as well. The patient should receive home exercises which he/she should do regularly.

Athletes must be directed in the process to return to the level prior to injury or even higher than normal. To succeed specific exercises have to be incorporated into the rehabilitation program. Not only the quadriceps muscle in the leg but also the pelvic stabilizers and the lateral trunk muscles have to regain force and dynamic stability.

To be able to return back to sports, the following measures should be fulfilled mostly after injury at six weeks :

- Absence of pain

- No effusion

- Complete range of motion: the range of motion is mostly corrected after six weeks when exercises are done. If not, the full range of motion might not be recovered.

- Symmetrical strength: Strength can be regained with quadriceps exercises as mentioned above. For high-demanding sports activities, the limb symmetry index (LSI) should be at least 90 percent.

- Dynamic stability: To achieve excellent dynamic lower limb stability, exercises with cutting tricks, side hops, and sudden changes of direction should be incorporated into the training program and performed on different surfaces.

- In the final phase, sport-specific such as plyometric and landing strategies for jumping sports, one-leg stability for material arts, cutting maneuvers and pivoting for team sports, proprioception, side stability, and landing capacities for skiers dominate the therapy.

To evaluate if the measures noted above are fulfilled, the following tests can help:

- Single-leg squat: To assesses dynamic stability. This test can also perform as an exercise, which is part of the exercise program.

Execution: Begin Squatting exercise on a single leg (compare both legs). Attention should be paid that the knee does not go into a valgus (laterally move )movement and stays above the foot. The pelvis must persist stable (no dropping or turning).

- Star Excursion Balance Test (SEBT): To estimate dynamic stability

- Drop jump test: evaluates control of the landing. This is significant for sports that demand to land from jumps (e.g. basketball, volleyball, etc)

Execution: The patient lowers from a box and lands on both feet, after which he/she directly jumps as high as possible for a second time. Pay attention to the balance of the reception, the alignment of both knees, the slowdown, and the capacity for sponging the shock.

- Side-hop test: Measure speed, agility, muscle coordination, limb alignment, trunk stability, and control in changing directions.

Execution: The patient may hop on one leg as often as possible during the age of 30 years between two lines at a distance of 40 cm.

Ideally, the patient has done them at the beginning of the therapy as well so that improvement can be registered during and after therapy. It might be worthwhile to film the test. This way it is more comfortable to examine the test, give feedback, and select new

exercises for the weak spots.

Nonsurgical treatment after Recurrent Patellar Dislocation

Nonsurgical treatment after Recurrent Patellar Dislocation

Surgery is not necessarily mandated for patients with patellofemoral malalignment or relaxation of the patella. Proper outcomes of surgery can be achieved with a conservative exercise program. It is very essential in the rehabilitation program to strengthen the quadriceps muscle and VMO(vastus medialis oblique). It is advised to follow the program in recurrent dislocation which is similar to that obeyed after acute dislocation, but with more resistive exercises to improve the strength. This program can also be begun early. In addition, a stabilization brace of the patella may support to prevention of chronic recurrent subluxation or dislocation.

Functional training. Once the pain reduces and the strength improves, the patient will need to safely transition into more demanding activities. The way the patient moves can impact the stability of her kneecap. The physical therapist will help to build kneecap stability and facilitate the chances of re-injury. They will teach patients secure, controlled movements. The physical therapist is an expert who can design a series of activities to help the patient move the body correctly.

Patient education. A physical therapist will work with the patient to identify and change any external factors causing the pain. This can include the type and amount of exercise a person does, and their footwear. They will look at all probable personal factors and recommend modifications. They will develop a specific exercise program designed to help patients return to their desired activities pain-free.

Specific postoperative care

A crucial part of knee dislocation surgery is postoperative rehabilitation.

Care after a posterolateral corner repair:

The knee is set in a Jones dressing and the knee brace is locked at 30° for 2 weeks to stimulate wound healing and to decrease stress on the peroneal nerve and popliteal artery. Active quadriceps exercises are initiated immediately. The early covered range of motion is crucial to prevent arthrofibrosis. When both cruciate ligaments are stretched, knee flexion is performed in the prone position to minimize the posterior tibial sag.

Care after Proximal realignment and MPFL reconstruction:

Normally, patients are motivated to weight-bear in a knee immobilizer or hinged knee brace locked in extension from up to 2 weeks after the knee operation. From 2 to 6 weeks postoperatively, patients may gain an active and passive range of motion of the knee from 0° to 90°. At 3 weeks postoperatively, closed chain quadriceps strengthening exercises are recommended, and this can progress to open chain exercises at 3 months postoperatively. Patients may then slowly return to non-contact sports, followed by a probable return to contact sports 4 to 6 months postoperatively.

Maintenance after surgery of Anterior-medialization of the tibial tubercle (Fulkerson osteotomy):

Rehabilitation typically involves protected weight-bearing with crutches and a knee immobilizer for 4 weeks to lower the risk of postoperative fracture. At 4 to 6 weeks, closed chain quadriceps strengthening exercises can be begun, with the expectation of a full recovery by 3 to 4 months. The patient should wait for activities that needed running and more forceful activities until 8 to 12 months postoperatively to permit maximum bony healing.

Post-Operative maintenance after lateral side ligament injuries due to dislocation of knee and rehabilitation with the Knee Symmetry Model (KSM):

When using the KSM for ACL postoperative rehabilitation the greatest goal of treatment is to regain the symmetry of the knees. The range of motion and strength become the prior objective measures of treatment

Already after the first week of bed rest, patients are allowed to continue normal daily activities. Full weight bearing with the immobilizer is encouraged and crutches are only used for support or balance until the patient is relaxed walking without them. When the patient can display that good leg control via good quadriceps activation and straight leg raises SLR, the leg immobilizer is discontinued. In some cases, damage to the common peroneal nerve can direct to foot drop conditions.

- A continuous passive motion (CPM) machine is initiated immediately after pursuing surgery. To evaluate the own range of motion, by doing Passive stretch, Heel slide, and Flexion exercises can be done.

- Strength testing is executed at 2 months after surgery. This possesses open kinetic chain (OKC) isokinetic testing at 180 and 60 ° per second speeds, an Isometric leg press test, and when appropriate, a single-leg hop test also done.

- Return to sports can only occur once the patient has achieved goals, like good stability, bilaterally symmetrical range of motion and strength, and he/she is satisfied with the rigors of their activity. Normally, patients back to sports from a lateral side knee ligament rehabilitation in 4-6 months after the operation.

Patients progress in accordance with their own unique restoring abilities and progression. The initial postoperative objectives of treatment are to control effusion and swelling. Rehabilitation of a symmetrical range of motion and strength is achieved according to patient tolerance

FAQs:

How do you rehab patellar instability?

Physical therapy exercises can strengthen muscles and connective tissue that hold the kneecap in the femoral groove. Cycling on an exercise bike or outside on an actual bike is also a good knee-strength exercise. Doctors may also recommend wearing a knee brace during certain activities

Are there any treatments to help fix a loose patella?

Arthroscopic surgery can fix this condition. If the kneecap is only partially dislocated, the doctor may recommend nonsurgical treatments, such as exercises and braces. Exercise will help strengthen the muscles in the thigh so that the kneecap stays aligned.

Does knee instability go away?

The treatment of knee instability relies on the severity of the injury. Some may heal on their own with rest and physical therapy, while others may require surgery for treatment.

What are the signs and symptoms of patellar instability?

A child may experience pain, swelling, stiffness, difficulty walking on the affected limb, and buckling, catching or locking sensations in the knee. Lastly, there may also be a prominent deformity in the affected knee.

Do knee braces help with instability?

The braces are designed to decrease knee instability following injury to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and to lessen additional injuries during athletic activities. They were initially marketed for use by athletes with knee joint instability who participated in activities that needed rapid direction changes.

One Comment