Trochlear Dysplasia

Trochlear dysplasia, also known as trochlear groove dysplasia or patellar dysplasia, is a condition characterized by an abnormality in the structure or alignment of the trochlea, which is the groove on the femur (thigh bone) that the patella (kneecap) slides along. This condition affects the stability and movement of the patella within the trochlear groove, potentially leading to patellar instability and recurrent dislocations or subluxations (partial dislocations).

The morphological abnormality of the femoral trochlea known as trochlear dysplasia has been linked to patellofemoral instability.

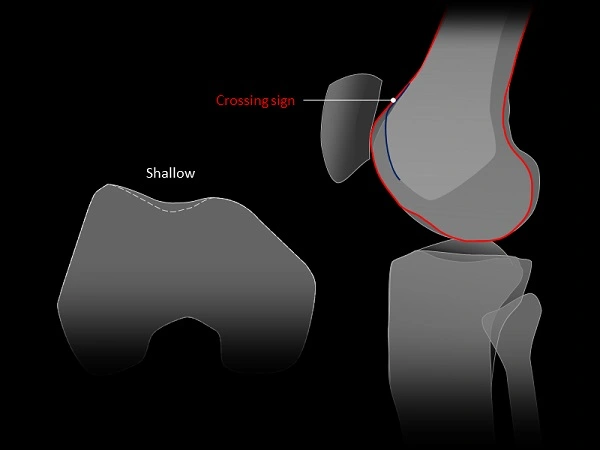

Knee trochlear groove anomaly known as trochlear dysplasia (TD). The line separating what is normal and what is abnormal is imperceptible. The guiding channel, into which the patella engages and slides, is the trochlear groove of the knee. The typical concave architecture is lost in TD; the depth of the groove is decreased and the configuration may shift. Most significantly, the TD is confined in the topmost end of the trochlea and is typically recognized as a shallow, flat, or even convex trochlea.

Table of Contents

Anatomy and Biomechanics of the Trochlea:

The patella serves a number of purposes in the human body, including aiding in quadriceps extension by lengthening the patellar tendon’s lever arm, concentrating the forces transmitted in multiple directions by the quadriceps’ four muscles, transferring tension from the femur to the patellar tendon, and anteriorly guarding the tibiofemoral joint. The patella and trochlea on the anterodistal end of the femur come together to create the patellofemoral joint during flexion and extension.

The medial and lateral aspects of the trochlea are divided from one another by a central groove that veers laterally from the axis of the femoral shaft and thickens distally. The sulcus angle, which averages 138° 6°, gauges the width of the groove. The patella connects with the lateral facet of the trochlea between 0° and 40° of extension, and this engagement stabilizes the patella in opposition to the quadriceps’ lateral pull. In contrast, the patella moves medially during flexion from 0° to 20°; once flexion reaches 20°, the patella catches and engages with the trochlea before moving medially until 90° of flexion.

What is trochlear dysplasia?

Under the patella (kneecap), on the femur bone, lies a groove known as the trochlea. As the knee bends, the patella is stabilized by the walls of the trochlea and is able to slide along the center of the trochlea. Because a centred patella boosts the power and effectiveness of the quadriceps of the thigh (knee extensor mechanism), it is crucial that the patella glides through the middle of the trochlea.

The trochlea does not always grow normally in some people. Some patients’ trochlear are flat or formed like a dome rather than having a groove. Trochlear dysplasia is the medical term for this issue. The patella loses stability and may track to the outside of the knee as the knee bends in a person with a flat or dome-shaped trochlea. When compared to someone with a normal trochlea, those with trochlear dysplasia are considerably more likely to dislocate their patella.

Any change in the trochlear architecture can have a significant impact on the biomechanics and stability of the patellofemoral joint since the patella interacts with the groove in both flexion and extension. Sulcus angles greater than 145° are used to quantitatively define dysplastic trochlear. The height of the patella, the lie of the patella, including patellar shift or tilt, and the distance between the tibial tuberosity and the trochlear groove (TT-TG) can all be impacted by these trochlear variations.

This increased sulcus angle manifests as a flattened, more shallow trochlear groove and can be caused by variations in facet height and/or groove depth. The medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL), the medial patellotibial ligament, and other nearby soft-tissue structures may also be affected by these anatomical changes and the VMO, or vastus medialis obliquus. The patient may have recurrent periods of atraumatic patellofemoral instability, which they feel as “giving way” or “dislocating,” when any of the aforementioned components are weakened or altered.

The term “trochlear dysplasia” describes a pathological change in the femoral trochlea’s form. The patella is more vulnerable to lateral subluxation or even dislocation if the trochlea is dysplastic, which might be shallower than usual or even flat or convex. A normal trochlea (also known as facies patellaris, intercondylar groove, or intercondylar sulcus) is sufficiently concave to guide and retain the patella throughout the normal range of motion.

Importance of the Proximal Trochlea:

The patella does not articulate with the femoral trochlea when the human knee is fully extended, especially if the quadriceps muscle is tensed. Instead, it lies just superolateral to the most superior part of the trochlea. The patella descends from this position and enters the trochlea at roughly 10° of knee flexion on each cycle.

The trochlea’s most proximal region, which the patella comes into contact with during early flexion, is the shallowest and hence provides the least stability for the patella. The patella is most prone to dislocation when articulating with this section of the trochlea. Therefore, even little deviations in this area of the trochlea have a significant impact on patellar stability. Patellar dislocation consequently frequently happens in the presence of patella alta because, in comparison to a normal patella, a patella that is located superiorly articulates with the proximal shallow portion of the trochlea for a longer period of time, increasing the risk for patellar dislocation.

The trochlear floor deepens and increases patellar stability as the patella advances distally with increasing knee flexion. The distal, or more inferior, sections of the trochlear groove are hence uncommon locations for the patella to dislocate. Because of this, any trochlear measurements that are crucial for figuring out patellar stability must be made at or just before knee flexion.

Pathology:

In addition to hypoplastic (small) or convex lateral femoral condyles, trochlear dysplasia can result in a shallow, flattening, or convex trochlear groove. Particularly during the transition from complete knee extension to early knee flexion, this dysplastic deformity of the most superior side of the femoral trochlea increases the risk of patellar dislocation. It is unknown what degree of dysplasia leads to patellar instability.

Although the origin of trochlear dysplasia is unknown, patellofemoral maltracking during development may be a contributing factor. Genetics and the breech posture may be risk factors.

Classification of trochlear dysplasia:

Dejour’s classification for trochlear dysplasia:

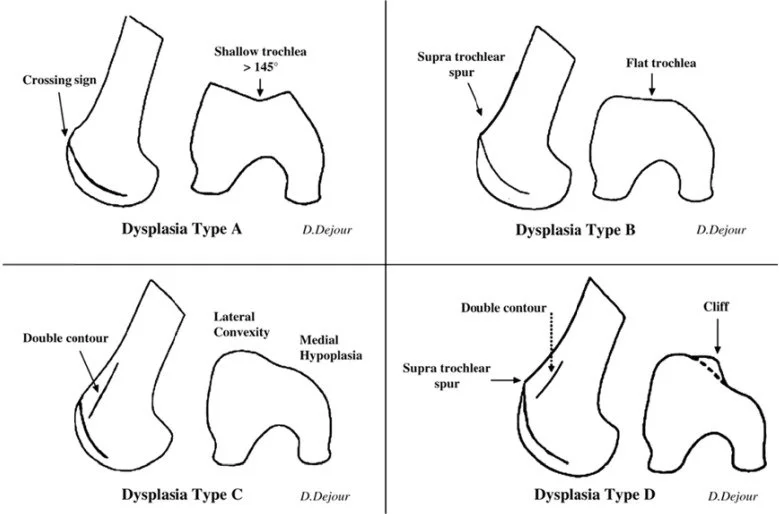

Type A: Type A with an isolated crossing sign. The existence of a crossing sign in the lateral view, a shallow trochlea, and a sulcus angle of more than 145° on the axial view (pretty shallow trochlea) are characteristics of type A.

Type B: Type B has a supratrochlear spur(a flat or convex trochlea) and crossing sign. On lateral radiographs, type B is distinguished by a crossing sign and supratrochlear spur (flat or convex trochlea).

Type C: Type C has a hypoplastic medial condyle, a crossing sign, and a double contour (asymmetry of the trochlear facets). A crossing sign and a double contour sign (asymmetry of trochlear facets with a hypoplastic medial condyle) on the lateral view are characteristics of type C.

Crossing signals, supratrochlear spurs, and double contour signs (asymmetry of trochlear facets plus vertical join and cliff pattern) are characteristics of type D.

Surgical management can benefit from this classification. High-grade trochlear dysplasia is difficult to define and is not generally accepted. Radiographic classifications as well as quantitative measurements are employed. According to many writers, high-grade trochlear dysplasia is similar to a type B or D trochlear dysplasia with a supratrochlear spur.

Symptoms of trochlear dysplasia:

- Knee discomfort and aches

- higher chance of instability and patellar dislocations

Diagnosis:

Trochlea dysplasia is often diagnosed following a complete physical examination and radiological work-up. When the knee is at full extension or at 45 degrees of flexion, patients with trochlear dysplasia frequently show greater medial and lateral patellar translation. Additionally, individuals could experience an anxiety test during which they fear their patella will laterally dislocate. On lateral knee X-rays, one can observe a “crossing sign” on plain X-rays, which would suggest that the trochlea groove is shallow and flat. The groove’s size would be less, it would flatten, and occasionally it would take on the shape of a dome on the 45-degree patella X-ray. The medial femoral condyle may exhibit some hypoplasia, or a reduction in size, on an anterior projection (AP) radiograph.

Physical Exam

The patellar position should be examined during a physical examination. The patella frequently sits high (patella alta) or too far to the side (lateral) of the knee. The inside of the knee’s muscles and joint lining may have torn if there is swelling or bruising. In order to determine if the patella rides in the proper spot in its groove, patellar tracking is assessed by having the patient bend and straighten their knee. A “J” symbol denotes the patella tendon being pulled in a direction that isn’t parallel to the trochlear groove. Although the intra and inter-observer reliability of the patellar apprehension test is only evaluated as fair to moderate and poor, it has been reported to have 100% sensitivity and 88.4% specificity.

Imaging

Imaging is utilized to support diagnosis because a physical examination by itself has its limits. The presence of a supratrochlear spur, the crossing sign, and the double contour sign are three frequent symptoms of trochlear dysplasia that can be seen on a lateral plain film. Together, these discoveries enable classification using the Dejour system.

A typical series of plain radiographs (x-rays) of the knee will reveal any patellar fractures as well as any other misalignments that might be causing recurrent instability or patellar instability. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) research is among other significant studies. To make sure there isn’t a cartilage fracture that might be repairable after the first dislocation, this is generally requested. Additionally, early MRIs will reveal tissue damage that can become more challenging to detect as oedema and inflammation subside.

Computed tomography (CT or CAT scan) can be used to confirm the kind of dysplasia into one of the four Dejour categories and perform other assessments that are useful in preoperative planning for reconstruction once the choice to have surgery has been made. The type of corrective operation needed and the degree of correction required are determined by measurements of the valgus alignment, sulcus angle, and tibial tubercle-trochlear groove distance.

Normal anatomy of imaging:

Three dense radiography lines are visible on the anterior part of the distal femoral epiphysis on a true lateral radiograph of the knee with flawless superimposition of the condyles posteriorly. The condyles’ two most anterior lines match their shapes. When performing flexion-extension motions, the patella and trochlea articulate at the trough of the trochlear groove, which is the curve immediately behind these lines.

Plain radiograph: Based on a true lateral knee radiograph, the initial assessment is:

- Crossing signal: the outlines of the lateral femoral condyle and the trochlear floor.

- Superolateral spur: Bony spur at the trochlea double contour sign’s most distal part.

- Trochlear Bump:The increased separation between the anterior trochlear groove and extension of the anterior cortex of the distal femur sulcus angle results in a much smaller medial femoral condyle trochlear bump.

CT: CT can show how the trochlea is shaped in three dimensions. Depending on the severity, it may appear on the axial imaging as a shallow or flat contour, a convexity of the lateral facet, a hypoplastic medial facet, or a pattern like a cliff.

MRI: Similar to CT, MRI will show abnormalities in the femoral trochlea’s cartilaginous contour as well as in its bony shape, which occasionally deviates from the osseous structure. Additionally, other assessment metrics have been described:

- Lateral Trochlear Inclination (LTI)

The most accurate measurement is called the Lateral Trochlear Inclination (LTI), which measures the angle between the lateral trochlear facet and a posterior condylar tangential line on the most cranial/proximal axial slice that contains trochlear cartilage. Trochlear dysplasia is indicated by an angle of less than 11° (reported sensitivity and specificity: 93%/87%).

- TD: Trochlear depth

Depending on whether bony or cartilaginous contours are employed, multiple techniques exist with various normal values. 8-10

A straightforward technique is to gauge the distance between the floor of the Trochlea and a line tangential to the medial and lateral facet’s most anterior points. Trochlear dysplasia is indicated if the depth is less than 3 mm.

- Posterior trochlear prominence

In a sagittal plane across the trochlear groove, the distance between the anterior cortex of the distal femur and the most anterior cartilaginous point suggests trochlear dysplasia (sensitivity and specificity: 75%/83%).

- Medial condyle trochlear offset (MCTO)

The distance between the medial condyle and a line drawn tangentially across the trochlear groove and perpendicular to the posterior surfaces of the femoral condyles is known as the medial condyle trochlear offset (MCTO).

One approach to compute it is (medial facet) / (lateral facet), which is the ratio of medial to lateral trochlear facet length.

In this instance, a ratio of 40% or lower denotes trochlear dysplasia.

Treatment:

Trochlear dysplasia should only be addressed when patellofemoral instability is present because it is a risk factor for it.

Patellar dislocation has been treated surgically using a variety of methods

Indications:

A flat or prominent trochlea that protrudes from the anterior femoral cortex, which prevents the patella from engaging the trochlea grove at around 25° of flexion, are symptoms of high-grade trochlear dysplasia.

Surgery, non-operative treatment, or trochleoplasty can be recommended as an indication in symptomatic patients with recurrent patellar dislocations and failure of prior patellar alignment.

Trocleoplasty, a procedure used to treat high-grade trochlear dysplasia, attempts to rectify the incorrect trochlear depth by re-creating a centred groove that allows the patella to enter more easily during early knee flexion.

There are several surgical methods for trochleoplasty, including:

- Deepening trochleoplasty of the sulcus

- Wedge-recession trochleoplasty

- lateral trochlear facet elevation

- Clinical findings appear to be type-dependent and to be improved following surgical correction of Dejour types B and D dysplasia.

The purpose of trochleoplasty is to recentralize the groove, rectify the incorrect trochlear depth, and stabilize the patella by improving the patella’s entry into the trochlear groove. Trochleoplasty may be suggested as a main technique for treating primary trochlear dysplasia or as a last resort in the event that earlier attempts to realign the patella have failed.

The trochleoplasty is recommended as a primary goal for a symptomatic patient with recurrent patellar instability who has not responded to non-operative treatment. In terms of pain, Kujala score, sports participation, and satisfaction, trochleoplasties performed for trochlear dysplasia type B or D produce better results than those performed for trochlear dysplasia without supratrochlear spur. A lateral facet elevation, proximal recession wedge trochleoplasty, or groove-deepening trochleoplasty may be necessary for Dejour type C trochlear dysplasia.

According to the anatomical anomalies, some authors advise conducting both trochleoplasty and MPFL repair in all dysplastic knees linked with another treatment.

The procedure of Trochleoplasty:

Potential candidates for a trochleoplasty include people who experience repeated patellar dislocations but do not show symptoms of patellofemoral arthritis or trochlear cartilage wear. To access the trochlea, the lateral capsule is opened during this procedure, and the patella is retracted medially. A new trochlear groove is sculpted into the exposed subchondral bone after the periosteum and trochlear cartilage are separated from it as a flap. The chondral flap is then stitched back over the groove after being replaced. If necessary, other procedures such as MPFL repair or tibial tuberosity osteotomy could be carried out concurrently. Patients can immediately put weight on their crutches after surgery while wearing an extension knee brace. During the first several days, passive movements is suggested. Strengthening the hamstrings and quadriceps should be the main emphasis of rehabilitation. Patients can begin running 12 weeks after surgery, and a gradual return to sports can commence after 6 months.

In most instances, additional surgeries are needed to repair the soft tissue injury and/or cartilage injury since patellar instability is a condition with a constellation of signs and disease. Each situation is unique, so a careful and tailored approach should be developed in each case before intervention to lower the risk of failure and increase the likelihood that this difficult condition can be solved successfully with a single definitive reconstructive surgery.

Prognosis:

Trochlear dysplasia can be exceedingly challenging to treat. The patient’s overall alignment, their tibial tubercle-trochlea groove angle (TT-TG), and an MRI scan to assess the condition of the articular cartilage of their patellofemoral joint should all be included in a full workup. This is crucial because even in cases when there is severe arthritis present, surgical therapies may not always be necessary. Additionally, a plain X-ray is recommended to assess the extent of patella alta, or a high-riding patella.

Trochlear dysplasia can be exceedingly challenging to treat. Patients with trochlear dysplasia have a substantially increased chance of lateral patellar dislocation recurrence. Treatment alternatives are also varied because the severity of trochlea dysplasia can range from mild to severe. The distal end of the femur may be cut and reshaped to create a more natural-looking groove during a trochleoplasty, a distal femoral osteotomy, or other related procedures. They can also entail the restoration of the medial patellofemoral ligament. The optimum course of action, if any, for a specific patient with trochlear dysplasia must be determined after a complete workup because no two patients receive the same treatment.

Post-operative treatment:

After a trochleoplasty, post-operative patients must avoid weight-bearing for six weeks. Additionally, patients are put inside a continuous passive motion (CPM) machine for 6 to 8 hours each day while not carrying any weight. For the first two weeks following surgery, motion is often limited to 90 degrees of knee flexion, and as tolerated, full knee motion is then added. At six weeks following surgery, when x-rays demonstrate adequate healing of the trochleoplasty, patients are permitted to begin weight bearing as tolerated and may wean off crutches once they can walk without one.

Starting with little resistance is also how one should utilize a stationary bike. Patients may begin endurance and agility workouts 3 months after surgery. After passing a sports test, typically 7-9 months after surgery, patients without arthritis in their patellofemoral joint are cleared to engage in full activities.

Physiotherapy treatment:

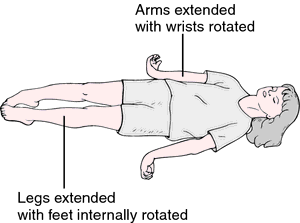

Physiotherapy treatment started on the day of the operation. Pumping movement of ankle started from 1st day.

Cold therapy: For Swelling and Pain.

Range of motion: CPM to increase range. After day 4, active assisted or passive knee flexion started.As movement possible, wall slides, lunges, low resistance cycle, hamstring, quads, gastrocnemius and soleus stretch.

Strengthening: Strengthening of hamstring and quadriceps.

- Start with isometric, Straight leg raise, active and resisted hip extension and abduction

- Step up and down activities

- Plyometric exercises

- Prone knee with or without weight

- heel raises

Gait training:

- Start with a weight transfer activity.

- Gait pattern

- Progress from 2 crushes to 1 to no crutch.

- Quick walk to jogging to running

- Walking on an uneven surface, slope

Manual therapy: Mobilisation

Proprioception on wobble board.

Massage on scar

Outcome:

A streamlined grading system for low-grade and high-grade trochlear dysplasia has been proposed in response to the need for a simplified method for trochlear dysplasia assessed on MR images. Additionally, this is a result of a weak correlation with the original Dejour classification system, which is regarded as being challenging to comprehend.

According to a review of the quality assessment of radiological measurements, the lateral trochlear inclination (LTI), the crossing sign, the trochlear bump, the TT-TG for treatment planning, the trochlear depth, and the ventral trochlear prominence are the metrics that are most useful for assessing trochlear dysplasia.

FAQs:

What exactly is trochal dysplasia?

A flat and/or prominent trochlea that protrudes from the anterior femoral cortex, which provides poor tracking during flexion and results in patellar dislocation, is a sign of high-grade trochlear dysplasia.

Does trochlear dysplasia occur at birth?

A shallow groove and aberrant trochlear morphology define trochlear dysplasia. Although it is linked to recurrent patellar dislocation, it is not known if the dysplasia is congenital, the result of lateral tracking and chronic instability, or the result of a mix of causes.

What trochlear dysplasia procedure is best?

A surgical treatment called trochleoplasty reshapes the trochlea to stop discomfort and disability brought on by recurring patellofemoral instability. A trochlea that has a spur (a bony protrusion), is flat, or convex is advised for surgery.

How is knee dysplasia treated?

The only procedure that can “cure” it is a partial knee replacement called a patellofemoral resurfacing arthroplasty, but this big operation, which includes implanting an artificial joint, is typically only performed on elderly patients or those who have severe symptoms and serious damage.

How long does it take to recover from trochlear dysplasia surgery?

You’ll need to miss three to four weeks of work. Following surgery, physiotherapy is started, focusing on recovering the range of motion and muscle strength. Your surgeon will provide you with a rehabilitation plan that gradually raises your degree of exercise while being supervised by a physiotherapist.