Superior Mesenteric Artery

Table of Contents

Introduction

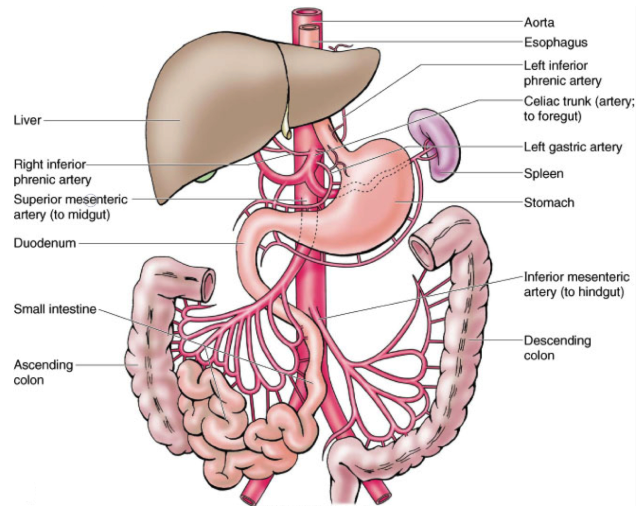

The superior mesenteric artery (SMA) is a major blood vessel in the human body, arising from the abdominal aorta just below the celiac artery at the level of the first lumbar vertebra

It begins at the level of the L1 vertebrae on the anterior surface of the aorta, about 1 centimetre below the celiac trunk and above the renal arteries. The pancreatic neck, the stomach’s pylorus, and the splenic vein are located anterior to the superior mesenteric artery.

Posterior to the artery lie the uncinate process of the pancreas, the inferior portion of the duodenum, and the left renal vein. The superior mesenteric artery’s takeoff and the aorta are where the left renal vein passes. The third section of the duodenum, the jejunum, the ileum, the cecum, the ascending colon, and the proximal part of the transverse colon are all supplied with blood by this artery.

The SMA supplies the entire small bowel (except the proximal duodenum) and the large colon up to the proximal half of the transverse colon. The ileocolic, inferior pancreaticoduodenal, intestinal, middle colic, and right colic arteries are among the branches of the SMA. The collateral channel that connects the SMA to the celiac trunk is made up of the superior and inferior pancreaticoduodenal arteries.

What is the superior mesenteric artery?

Major arteries in the belly include the superior mesenteric artery (SMA). It originates in the abdominal aorta and provides vascular blood to the midgut’s organs, which extend from the duodenum’s major duodenal papilla to the proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon.

The artery divides into many arteries, such as the intestinal, ileocolic, inferior pancreaticoduodenal, and left and right colic arteries.

The superior mesenteric artery is linked to two recognized pathological conditions: superior mesenteric artery syndrome and nutcracker syndrome. When the renal vein is compressed by the artery, it results in Nutcracker syndrome. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome, in which the artery compresses the duodenum, is not the same as this. The accumulation of fat that causes atherosclerosis is not a problem.

Anatomy:

The gastrointestinal tract is composed of three main sections. The midgut, hindgut, and foregut are these. The ampulla of Vater drains into the duodenum at the main duodenal papilla, which is the location of the foregut’s extension from the mouth. From this point on, the midgut stretches to the proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon. From this point forward, the hindgut extends to the anal canal’s dentate line. The superior, middle, and inferior rectal arteries provide blood to the rectum.

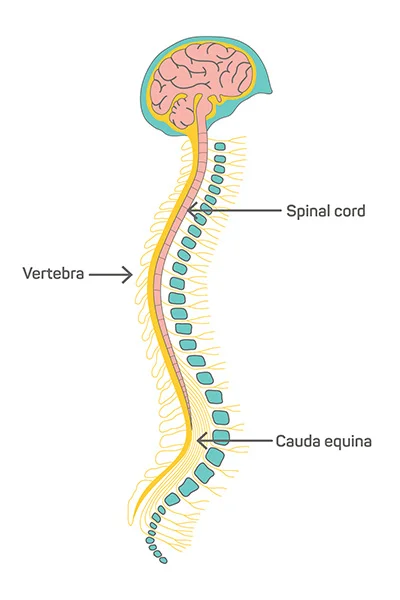

A centimetre or so below the celiac trunk, the superior mesenteric artery emerges from the abdominal aorta at the level of the first lumbar vertebral body L1. It emerges at the level of the vertebrae L1–L2, above the renal arteries. The inferior mesenteric artery supplies the hindgut, while the superior mesenteric artery supplies the midgut. Every one of these arteries gives rise to other main branches that nourish different parts of the digestive system.

The superior mesenteric artery begins its journey posteriorly, going forward and downward to the splenic vein and the pancreatic neck. Typically, the superior mesenteric artery runs to the left of the superior mesenteric vein (which serves the same area that the artery feeds).

Similarly, the thoracic and lumbar splanchnic nerves, or T5-T9, T9-T12, and L1-L2, respectively, are the source of the sympathetic inputs to the foregut, midgut, and hindgut. The vagus nerve (cranial nerve 10) supplies parasympathetic innervation to the foregut and midgut, whereas the pelvic splanchnic nerves supply parasympathetic innervation to the hindgut.

Structure

Origin

The SMA emerges in adulthood, anterior to the inferior border of the L1 vertebra. Usually, it is one centimeter lower than the celiac trunk.

Course and relation

It begins its journey anteriorly and inferiorly, going beneath and behind the splenic vein and the pancreatic neck. The following are situated between the aorta and this section of the superior mesenteric artery, beneath it:

- The left renal vein runs between the left kidney and the inferior vena cava; at this point, it may become pinched between the abdominal aorta and the SMA, which can result in nutcracker syndrome.

- The small intestine, which makes up the third segment of the duodenum, may be crushed by the SMA at this point, resulting in superior mesenteric artery syndrome.

- The pancreatic uncinate process is a little portion of the organ that surrounds the SMA.

The superior mesenteric vein, with which it is connected, is usually located to the left of the SMA. It begins to release its branches once it has passed through the pancreatic neck.

Major branches:

The small intestine, cecum, ascending colon, and a portion of the transverse colon are subsequently supplied by a number of branches that arise from the superior mesenteric artery.

Branches are:

- Middle colic artery (Arteria colica media)

- Inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery

Inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery: The inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery is the initial branch of the superior mesenteric artery, originating from its right side. It supplies blood to both the inferior and head of the pancreas and ascending areas of the duodenum. The anterior and posterior branches are the two additional branches that this artery produces.

It develops into anterior and posterior vessels, which anastomose with branches of the celiac trunk-derived superior pancreaticoduodenal artery. This network nourishes the duodenum, the uncinate process, and the inferior part of the pancreatic head. The pancreatic head and the duodenum’s C-shaped internal curvature are separated by both branches. They anastomose with the gastroduodenal artery’s terminal branch, the superior pancreaticoduodenal artery.

The Right and Middle Colic Arteries

From the right side of the superior mesenteric artery, the right and middle colic arteries emerge to nourish the colon.

The middle colic artery supplies blood to the transverse colon.

The right colic artery supplies blood to the ascending colon.

- Middle colic artery:

- The proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon are supplied by this second branch, which arises from the right side of the superior mesenteric artery. It emerges right below the pancreas and ascends through the transverse colon’s mesentery. The artery to which its left and right branches anastomose is the left colic artery, which is a branch of the inferior mesenteric artery, while the artery to which its right branch anastomoses is the right colic artery.

- Right colic artery: The right colic artery nourishes the ascending colon and flows directly to the right. This portion of the colon travels anteriorly through the psoas major and gonadal vessels (together with the retroperitoneal ureter); these vessels are located within the greater omentum, a quadruple layer of peritoneum. It splits into two branches, one climbing and one lowering. The ileocolic artery is the anastomosis point for the latter, and the middle colic artery for the former.

Ileocolic artery: The superior mesenteric artery’s last major branch is the ileocolic artery. It flows inferiorly and to the right, branching out to form the ileum, appendix, colon, and cecum. The appendicular artery is ligated when an appendectomy is performed. The ileum, appendix, and caecum are supplied by this artery. It goes down and to the right to meet the ascending colon.

The ileal branch of the ileocolic, which provides the junction between the ileum and the caecum, the anterior and posterior cecal arteries (which serve their respective portions of the caecum), and the appendicular artery, which supplies the appendix, are among its other branches. Since the appendicular artery is an end artery, blockage of this artery could result in ischemic necrosis of the appendix. The ascending colon is supplied by the superior colic branch.

Jejunal and Ileal branches: Branching out from the left side of the superior mesenteric artery, the jejunal and ileal arteries supply the jejunum and ileum. They create arterial arcades, which are arteries that supply the colon close by. The jejunum’s arcades are longer and have fewer anastomoses or connections between them. The ileum’s arcades have more anastomoses and are shorter in length. This illustrates how the different sections of the bowel work. The small intestine is not directly supplied by the arterial arcades. Finally, they nourish the small intestine by means of the so-called straight arteries (arteriae recta), which are longer than the arcades.

Marginal artery of Drummond: The marginal artery forms at the internal border of the colon as a result of the anastomosis of the terminal branches of the inferior mesenteric artery (left colic and sigmoid arteries) and superior mesenteric artery (middle colic, right colic, and ileocolic arteries). The artery was initially described by Sir David Drummond. In terms of surgery, the marginal artery is adequate to perfuse the colon during bowel resection, when the larger arteries may be clamped off to reduce blood loss.

Function:

A peripheral artery in the body’s vascular system is the superior mesenteric capillary. Blood is transported throughout the body by arteries from the heart. Peripheral arteries circulate blood towards areas of the body that are distant from the heart.

Blood is supplied by the superior mesenteric artery to:

- Pancreas.

- The small intestine includes the duodenum (the portion that joins the stomach and small intestine).

- Large intestine.

Clinical significance:

Compared to other veins of similar size, the SMA is mostly resistant to the effects of atherosclerosis. Perhaps protective hemodynamic conditions are at the root of this.

Up to 80% of SMA occlusions result in mortality, and acute occlusions nearly always cause intestinal ischemia and other severe outcomes.

Superior mesenteric artery syndrome (SMA) can result from compression of the third (horizontal) segment of the duodenum or the left renal vein, causing nutcracker syndrome.

The following illnesses can have an impact on the superior mesenteric artery:

- Mesenteric ischemia: This illness is brought on by an obstruction that reduces or completely prevents the flow of blood to the gut. A blood clot (thrombus) or plaque deposits of fat and cholesterol (atherosclerosis) can result in a partial or total blockage of an artery.

- Mesenteric aneurysm: An enlargement of the superior mesenteric artery that may cause the blood vessel wall to weaken and eventually burst.

- Nutcracker syndrome: The aorta and superior mesenteric artery compressing the left renal vein, also known as the kidney vein, is known as “nutcracker syndrome.” This vein leads from the kidneys to the filtrated blood. The compression may cause blood in the urine, pelvic congestion, or flank pain.

- Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: This uncommon medical condition is brought on by the superior mesenteric artery and the aorta compressing the duodenum. Food does not escape the stomach, and eating discomfort is avoided thanks to the compression.

- Lower GI bleeding

- SMA stenosis

- SMA thrombosis

Summary

Compression of the third segment of the duodenum, or the upper portion of the small intestines just past the stomach, is the cause of the uncommon illness known as superior mesenteric artery syndrome (SMA syndrome). This disorder arises from compression of the third segment of the duodenum between the abdominal aorta (AA), the body’s main artery, and the SMA, one of its branches.

The small intestine and the first segment of the colon receive blood flow from the SMA. Malnutrition and weight loss can result from the inability to get enough nutrients due to compression of the SMA against the AA, which can prevent duodenal contents from draining into the jejunum (upper small intestine). Debilitating pain from the compression might result in “food fear” and make the situation worse.

Vomiting and nausea are signs that the duodenum is compressed. Persistent weight loss exacerbates compression and obstruction because it reduces the mesenteric fat pad, and, as a result, the angle between the SMA and AA diminishes. Early detection and intervention are critical to preventing serious side effects or death.

FAQs

What does the superior mesenteric artery do?

The intestines receive nutrition and oxygenated blood from the superior mesenteric artery. The digestive system includes these organs. The aorta, the biggest blood vessel in the body, is where the artery splits off. The artery’s position above other arteries supplying the intestines is referred to as superior.

What are the symptoms of superior mesenteric artery disease?

Symptoms may include dyspepsia, vomiting, nausea, and abdominal discomfort. Early satiety is a condition in which a person feels full after consuming very little food or liquids because their stomach is not emptying. The stomach is still full of food or liquids from hours before.

At what age does superior mesenteric artery syndrome occur?

Less than 0.3% of the population has been reported to have SMA syndrome. The majority of patients are in their teens or early adult years, ranging from 10 to 39 years old, though there have been reports of older patients. Anorexia nervosa may be the cause of a slightly higher prevalence in females.

What occurs when there is a blockage in the superior mesenteric artery?

A blockage in an artery stops blood flow to a section of the intestine when it occurs in mesenteric ischemia. A disease known as mesenteric ischemia occurs when blood flow to your small intestine is restricted by narrowed or blocked arteries. The small intestine may sustain long-term injury from reduced blood supply.

Does a severe mesenteric artery pose a hazard to life?

A rare, but potentially fatal, condition is superior mesenteric artery syndrome.

References:

- Professional, C. C. M. (n.d.). Superior Mesenteric Artery. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/21679-superior-mesenteric-artery

- The Superior Mesenteric Artery—Position—Branches—TeachMeAnatomy. (2022, December 10). TeachMeAnatomy. https://teachmeanatomy.info/abdomen/vasculature/arteries/superior-mesenteric/

- Superior mesenteric artery. (2023, February 20). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Superior_mesenteric_artery

- Superior mesenteric artery. (2023, July 25). Kenhub. https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/superior-mesenteric-artery

- Superior mesenteric artery. (2018, January 24). Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/human-body-maps/superior-mesenteric-artery#1

- Gurarie, M. (2022, April 23). The Anatomy of the Superior Mesenteric Artery. Verywell Health. https://www.verywellhealth.com/superior-mesenteric-artery-anatomy-4800189

2 Comments