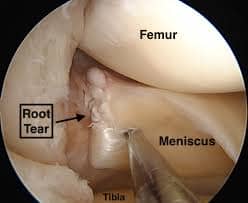

Meniscus Tear At The Root

Table of Contents

Definition

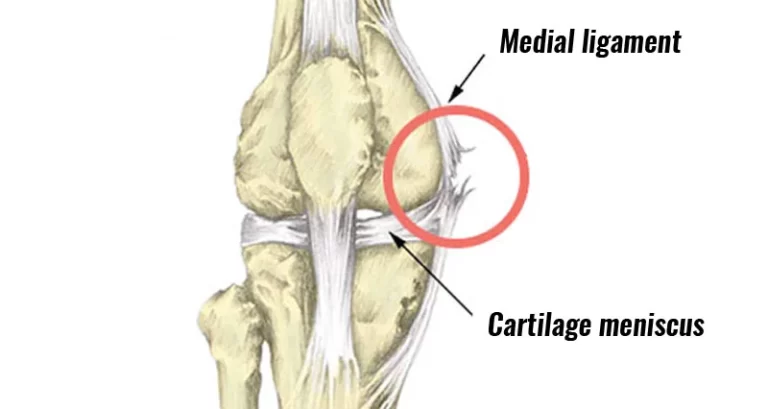

A Meniscus tear at the root is a common orthopedic injury that affects the knee joint. The meniscus is a wedge-shaped cartilage structure that acts as a cushion and stabilizer within the knee, providing support and allowing for smooth joint movement. When a tear occurs at the root of the meniscus, it typically involves the attachment point of the meniscus to the tibia bone, near the joint’s inner edge.

This type of tear is significant because the meniscus’s root plays a crucial role in maintaining knee stability and preventing the development of osteoarthritis. A tear at the root can lead to a range of symptoms, including pain, swelling, limited range of motion, and instability in the knee joint. Prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment are essential to address this injury effectively and prevent long-term joint damage.

This condition has been called a “silent epidemic” – only becoming apparent in the last decade. This is probably because meniscal tears, despite their severity, are challenging to recognize and treat appropriately. Meniscal root tears are not always seen in MRI or arthroscopy; however, knee specialists look for these injuries because they could be issues if ignored.

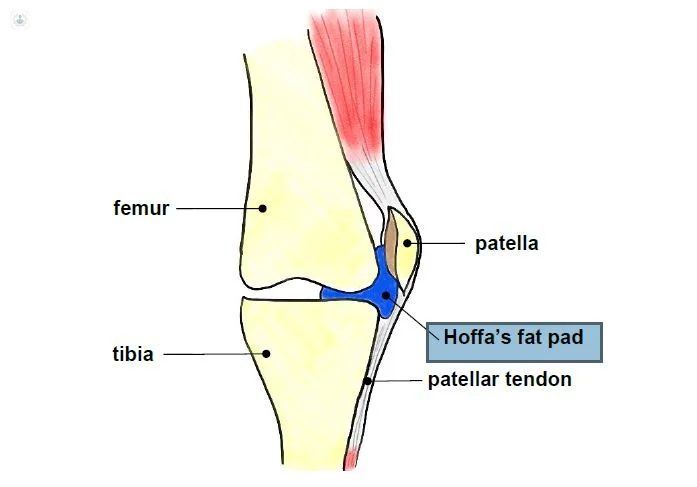

The meniscus is a wedge-shaped cartilage between the knee joint’s tibia (shinbone) and femur (femur). There are 2 menisci per knee – one on the inside called the medial meniscus and one on the outside called the lateral meniscus in the body. The function of the meniscus is to distribute vertical loads over a larger surface area, promote shock absorption, provide secondary rotational stability, and protect the articular cartilage that lubricates the ends of the tibia and femur so they line up smoothly. every walk or run. It is clear that the meniscus plays an essential role in the kinematics and biomechanics of the normal knee! Classification of meniscus Tear Root

Anatomy of Meniscus Tear Root

Meniscal roots have attachment sites for primary and accessory fibers that significantly affect the original attachment areas and root attachment strengths. Therefore, previous anatomical studies must be interpreted based on whether they included accessory fibers.

Medial Meniscal Posterior Root Attachment (MPRA)

The MPRA is 9.6 mm posterior and 0.7 mm lateral to the medial tibial eminence (MTE), the most reproducible bony landmark. In addition, the center of the MPRA is 3.5 mm lateral to the cartilage pivot and 8.2 mm just proximal to the tibial attachment of the PCL, which represents two other adjacent landmarks.

Medial and lateral fixations of the posterior root of the meniscus and significant arthroscopic bony landmarks. anterior cruciate ligament; LPRA, lateral meniscal posterior root attachment; LTE, lateral tibial eminence; MPRA, medial meniscal posterior root attachment; MTE, tibial eminence; PCL, posterior cruciate ligament bundles; SWF, bright white fibers of the posterior horn cells of the medial meniscus in the knee. quantitative and qualitative anatomical analysis of the posterior root attachments of the lateral and medial menisci.

Fixation of the posterior root of the lateral meniscus (LPRA)

The LPRA is situated 1.5 mm posterior side and 4.2 mm medial side to the lateral tibial side eminence (LTE). In addition, the center of the LPRA is 4.3 mm medial to the flexion of the lateral cartilage and 12.7 mm just anterior to the most proximal part of the tibial attachment of the PCL.

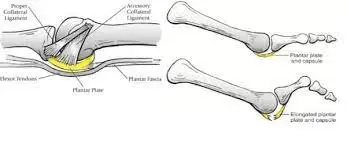

Medial Meniscus Anterior Root Attachment (MARA)

The MARA is located along the anterior intercondylar ridge of the anterior slope of the tibia. The center of the MARA was known to be 18.2 mm from the midpoint of the anteromedial tibial anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) footprint and 27.5 mm from the anterolateral tip of the medial tibial eminence. MARA has a risk of tibial fractures during intramedullary nailing.

The anterior lateral (AL) glenoid root has been shown to run deep down and overlap the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), as seen in all knees. The anterior medial (AM) meniscal root is described by supplementary fibers (SF), which were found to be anterior and distal to the medial root. The structure of the anterior meniscal root is also described in relation to significant bony and soft tissue landmarks. AC, articular cartilage; LTE, lateral tibial eminence; MTE medial tibial eminence; Posterior Lateral root, posterior lateral meniscal root; PM root, posterior medial meniscal root; CT, tibial tuberosity.,

Fixation of the anterior root of the lateral meniscus (LARA)

LaPrade et al reported a mean LARA area of 140.7 mm2, due to the significant overlap with the ACL sign. In addition, the LARA site was 5.0 mm at the midpoint of the anterolateral ACL footprint, 14.4 mm at the lateral tibial eminence, and 7.1 mm at the proximal edge of the lateral articular cartilage. Therefore, LARA has a high risk of iatrogenic injury during ACL-tibial tunnel abrasion

Epidemiology of meniscus Tear Root

Meniscal roots have an important function for the meniscus to convert axial tibiofemoral loads into ring stresses. Loss of the meniscal attachment point to the tibial plateau results in loss of normal meniscal function, meniscal compression, and altered knee joint kinematics. This results in uneven and abnormal load distribution at the knee joint, which reduces the tibiofemoral contact area and increases the peak contact pressure. Allaire et al reported that MPRA excision resulted in a 25% increase in mean contact pressure from baseline, comparable to total meniscectomy. Similar changes in the knee loading profile have been reported in LPRA avulsions. Increased contact pressure caused by meniscal root tears is damaging to articular cartilage and can lead to early OA if not adequately treated.

In cases with ACL deficiency, the posterior root of the LM plays an important role in stabilizing the knee during both anterior tibial translation (ATT) and rotation. Therefore, possible LPRT should be suspected in patients with Lachman grade 3 and 3 turning point changes. LPRA has also been reported to act as a primary stabilizer for internal rotation at higher flexion angles. Based on these biomechanical findings, LPRT repair should be performed concurrently with ACL reconstruction to avoid continued instability and increased forces on the ACL graft. Although there is still speculation about whether the shiny white fibers (SWF) and accessory fibers should be considered part of meniscal root fixation, biomechanical studies have shown that they contribute significantly to their ultimate breaking strength in the posteromedial, posterolateral, and anteromedial directions. roots Therefore, Ellman et al suggested that the involvement of these fibers during repair may be the reason why some surgical techniques do not adequately restore the biomechanics of the knee. Nonanatomic repair has also been reported to have important consequences for the long-term health of the tibiofemoral joint.

In porcine and human models, recent studies reported that non-anatomical transtibial retraction of medial articular roots, attached only 3–5 mm from the original site, significantly increased mean contact pressure and reduced contact area during tibiofemoral loading. Therefore, anatomical correction is necessary to reduce the harmful factors influencing the progression of osteoarthritis. The 2-tunnel transtibial pullout repair technique has become popular among doctors because of its ability to restore tibiofemoral contact pressure and contact layer at zero time.

It has also been suggested that the transtibial extraction technique has the added benefit of synovial healing due to the biological effect of tunneling, which allows growth factors and progenitor cells to exit the bone marrow. However, microdisplacement of the articular root caused by the long suture, or the “bungee effect”, was a concern, but Cerminara et al. reported that a defect in the meniscus-suture interface rather than a “bungee effect” was the main cause of root displacement.

Diagnosis

A detailed history, physical examination, and enhanced imaging (MRI) can diagnose most sprains. Meniscal tears at the edge (meniscocapsular or oblique tears and lateral tears of the connective tissue) are notoriously tricky to diagnose and experience is required to make an accurate diagnosis. For patients living in Vail, Aspen, and the surrounding communities of Denver, Colorado, Dr. Vidal discusses symptoms and examines the injured knee.

Clinical evaluation of meniscus tear root

Medical History: The healthcare provider will ask you about your symptoms when they started, and any specific incidents that might have caused the injury. Information about your overall health, past hurts, and activity level will also be collected.

Physical Examination: The doctor will perform a thorough physical examination of the knee joint. They will look for signs of swelling, tenderness, and deformities. Specific tests might be conducted to assess the stability and range of motion of the knee.

McMurray Test: This is a specific test used to detect meniscus tears. The doctor will manipulate your knee joint while bending and rotating it. This movement can cause pain or clicking if there’s a meniscus tear present.

Joint Line Tenderness: The doctor will press along the joint line of the knee to check for tenderness. Tenderness at specific points can indicate a meniscus tear.

Locking and Catching: The doctor will inquire if you’ve experienced any episodes of the knee “locking” or “catching” during movement, which is a common symptom of a meniscus tear.

Range of Motion Assessment: The doctor will assess your ability to bend and straighten your knee fully. Limited range of motion might suggest a meniscus tear.

Pain and Swelling: The location and type of pain you’re experiencing can give clues about the possible location and severity of the tear.

Other Tests: In some cases, the doctor might also perform additional tests such as the Apley grind test or Thessaly test to further evaluate the meniscus.

Medical Treatment

Conservative Management: For minor tears or tears that aren’t causing significant symptoms, conservative management might be recommended. This could involve rest, ice, anti-inflammatory medication, and physical therapy to strengthen the surrounding muscles and improve stability.

Surgical Options:

Meniscal Repair: In cases where the tear is repairable and located near the root, a surgeon might opt for a meniscal repair. This involves suturing the torn meniscus back to its attachment on the bone. This approach aims to preserve the meniscus and its function.

Meniscectomy: If the tear is extensive or located in an area where repair is not feasible, a partial meniscectomy might be considered. This involves removing the damaged portion of the meniscus while preserving as much of the healthy tissue as possible.

Root Repair: In some cases, surgeons might perform a root repair surgery. This involves reattaching the meniscus to the bone using various techniques, such as sutures or anchors. This is done to restore the stability and function of the meniscus.

Rehabilitation: Rehabilitation is a crucial part of the treatment process, whether surgery is performed or not. Physical therapy can help restore strength, flexibility, and range of motion to the knee joint. A physical therapist will work with the patient to develop a customized program based on their specific needs.

Bracing: Depending on the severity of the tear, a knee brace might be recommended to provide support and stability to the joint during the healing process.

Activity Modification: Patients may need to make certain modifications to their daily activities and sports participation to prevent further strain on the healing meniscus.

Physiotherapy treatment

Initial Rest and Pain Management: Resting the knee initially helps to reduce inflammation and pain. Ice and elevation might also be recommended to manage swelling.

Range of Motion Exercises: Gentle range of motion exercises can help prevent stiffness in the knee joint. These exercises are typically started early in the recovery process to prevent loss of mobility.

Strengthening Exercises: Strengthening the muscles around the knee joint, especially the quadriceps and hamstrings, can help provide better stability and support to the injured area. Your physiotherapist will design a program that gradually progresses in intensity.

Balance and Proprioception Training: Working on balance and proprioception (awareness of your body’s position in space) can help improve overall joint stability and reduce the risk of further injury.

Modalities: Physiotherapists might use modalities such as ultrasound, electrical stimulation, or manual therapy techniques to help with pain management and tissue healing.

Functional Exercises: As you progress, your physiotherapist will likely introduce exercises that mimic the movements and activities you need to perform in your daily life or sports. This helps ensure that your knee can handle real-world stresses.

Gradual Return to Activities: If you are an athlete or have specific physical demands, your physiotherapist will work with you to create a gradual and safe plan for returning to your desired activities.

Patient Education: Learning about proper body mechanics, posture, and movement patterns is essential to prevent further strain on the meniscus and the knee joint

Exercise for meniscus Tear Root

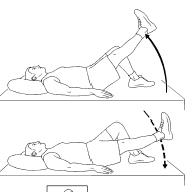

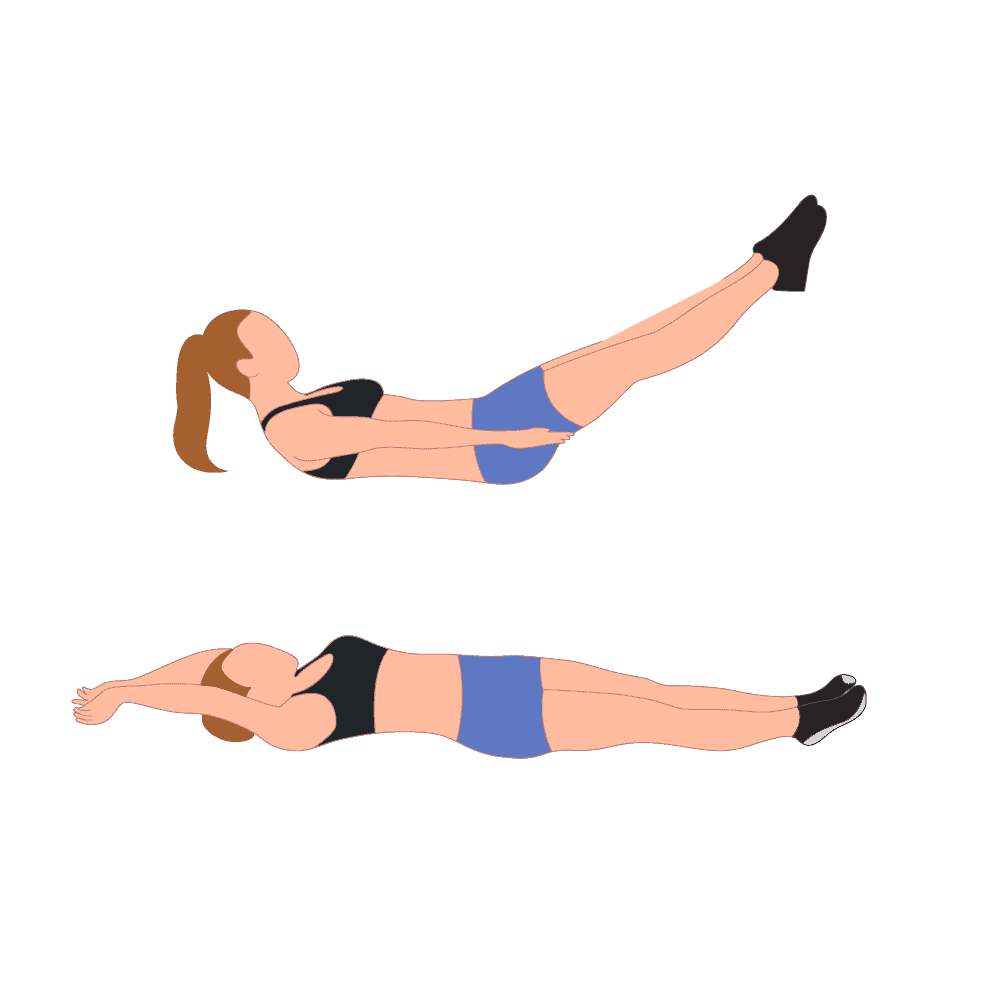

Straight Leg Raises: Sit on a stable surface with your legs outstretched.

Tighten the quadriceps muscles of your injured leg and lift it off the ground while keeping your knee straight.

Hold for a few seconds and then lower the leg down.

Perform several repetitions.

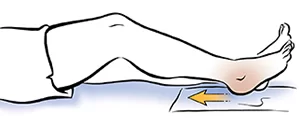

Heel Slides:

Keep your legs outstretched, and lie on your back.

Gently bend your injured knee and slide your heel toward your buttocks.

Slowly slide the heel back to the beginning position.

Repeat this movement for a certain number of repetitions.

Quad Sets: Sit on the floor with your legs extended straight in front of you.

Push your injured knee down onto the floor, engaging your quadriceps muscles.

Hold for a few seconds and release.

Perform several sets of repetitions.

Partial Squats: Stand with your feet shoulder-width apart and hold onto a stable surface for support.

Bend your knees slightly and perform partial squats, keeping the movement controlled and pain-free.

Make sure the patient’s knees don’t go beyond his toes.

Slowly return to the starting position.

Stationary Bike (Low Resistance): Cycling on a stationary bike with low resistance can help promote knee mobility and gentle strengthening.

Seated Leg Extensions: Sit on a chair with your feet flat on the floor.

Slowly extend your injured leg outward, straightening the knee.

Hold for a few moments and then lower the leg back downside.

Avoid any sudden or jerky movements.

Clamshells: Lie on the patient’s side with his legs bent at a 90-degree angle.

Keep the patient feet together and lift his top knee while keeping his feet touching.

Lower the knee back down.

This exercise targets the muscles around the hip and can help with hip stability, which indirectly supports the knee.

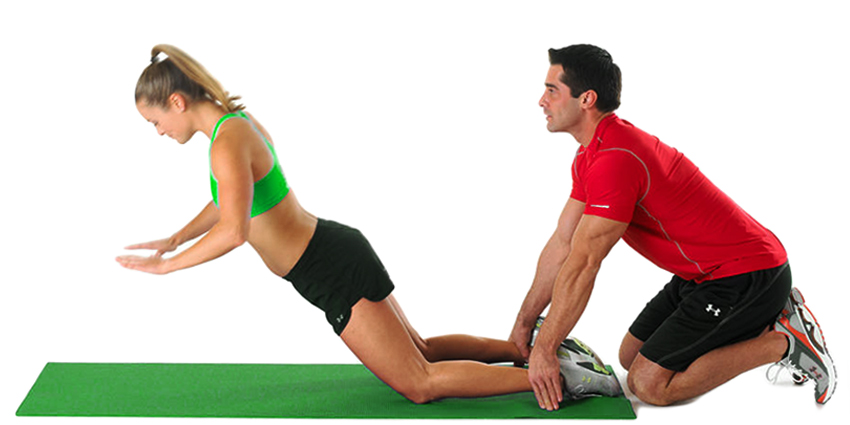

Hamstring Curls: If your healthcare professional approves, you can try gentle hamstring curls.

Lie on your stomach and slowly bend your knee, bringing your heel toward your buttocks.

Hold for 5 to 10 seconds and then lower the patient’s leg back downside.

This can help with strengthening the back of your thigh.

Ankle Pumps: While lying down, gently move your ankle up and down in a pumping motion.

This exercise helps improve blood circulation and prevents stiffness.

Bridging: Lie on the patient’s back with his knees bent and feet flat on the floor.

Slowly lift your hips off the ground while keeping your feet and shoulders on the floor.

Hold for 5 to 10 seconds, then lower the patient’s hips back down.

This exercise helps strengthen your glutes and lower back muscles, which can contribute to overall knee stability.

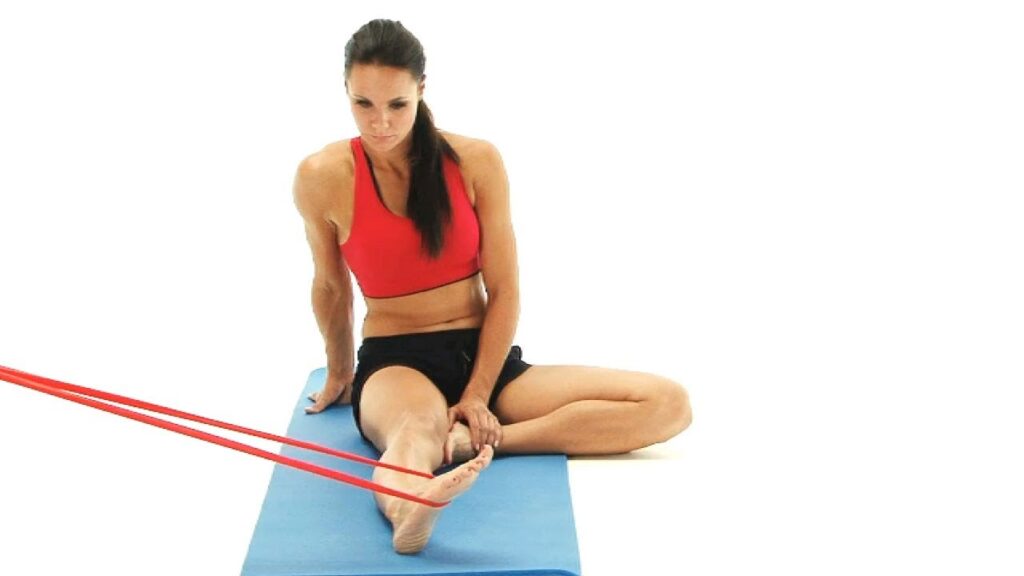

Resistance Band Exercises: Attach a resistance band to a sturdy surface and loop it around your injured ankle.

Perform gentle leg abduction (moving your leg away from your body) and leg adduction (moving your leg toward your body) against the resistance of the band.

You can also try seated leg presses with the band for some controlled strengthening.

Wall Sit with Ball Squeeze: Stand against a wall and slide down into a seated position, as if sitting in an imaginary chair.

Place a ball or cushion between your knees and gently squeeze it.

Hold the squeeze for 5 to 10 seconds, then release it.

This exercise engages your inner thigh muscles and promotes knee stability.

Pilates Leg Circles: Lie on your back with your arms extended out to the sides.

Lift your injured leg off the ground and draw small circles in the air with your foot.

Perform circles in both the legs clockwise and counterclockwise directions.

This exercise helps with hip and knee mobility.

Swiss Ball Hamstring Curl: Lie on your back with your feet on a Swiss ball.

Lift your hips off the ground to create a straight line from your shoulders to your heels.

Bend the patient’s knees to roll the ball toward his buttocks.

Slowly extend your knees to roll the ball away from you.

This exercise can gently engage your hamstrings and glutes

Surgical treatment

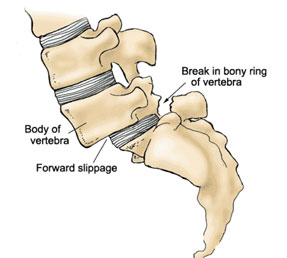

Treatment for meniscal root tears varies depending on the severity of the injury, the timing of the harm related to the surgical procedure, and the condition of the articular cartilage. The goal of surgical repair is to restore joint contact pressure, and joint kinematics and delay the development. Therefore, surgical repair is not recommended in patients with diffuse Outerbridge grade 3-4; However, it may be considered for symptomatic relief in patients with focal chondral defects. The most commonly used treatments for meniscus tear at the root of are non-surgical treatment, partial meniscectomy, or repair.

Non-operative treatment

Recent evidence on the importance of the posterior condylar roots in maintaining circumferential tension, normal knee kinematics normal contact loading; and excellent postoperative patient-reported outcomes and established surgical techniques; there are some scenarios where a root laceration is not treated with surgical repair. Elderly patients with high-grade and diffuse OA (Outerbridge 3-4) are usually non-operative candidates. Symptomatic treatment with analgesics (oral or topical), activity modification, and/or voiding support may relieve some symptoms.

Meniscectomy

Patients with advanced degenerative changes and persistent mechanical symptoms (e.g., locking) who have failed conservative treatment may benefit from partial or subtotal meniscectomy (42). However, further progression of OA occurs reliably, making symptomatic relief often short-lived, unlike synovial root surgery.

Posterior meniscal root repair

Anatomic repair of the meniscal root should be attempted whenever possible to prevent meniscal damage and OA, except in cases where the patient is a poor surgical candidate (with significant comorbidities or the elderly), ipsilateral diffuse Outerbridge grade 3 or 4 OA, asymptomatic chronic meniscal root. tear, and/or considerable limb imbalance if not corrected at the same time. The 2 more commonly used repair techniques are suture anchor repair and transtibial meniscal root repair in the body.

Suture anchor repair

Medial meniscal root tears can be treated with suture anchor repair, which uses a single suture anchor in a two-suture all-internal technique. In MPRT, the anchor is placed in the anatomical footprint of the meniscal root using a high posteromedial portal. The heart is then fixed again with two vertical stitches. This technique is technically demanding and has been reported mainly in patients with grade 3 medial ligament tears.

Transtibial dislocation repair

Many techniques have been described describing suture fixation of medial and lateral posterior root tears. Treatment may vary slightly depending on the type of meniscal root tear. This special technique involves pulling sutures through the root of the meniscus, pulling them through tunnels drilled into the proximal tibia, and then tying them over a post, button, or anterior tibial bridge. Many meniscal suture configurations with different biomechanical properties have been proposed, including two simple sutures, a horizontal mattress suture, a modified Mason-Allen (MMA), and two modified loop sutures. However, these two simple sutures were reported to cause the least amount of root displacement, and increased stiffness, and are not significantly different from the more complex (MMA) sutures. One-tunnel and two-tunnel techniques have been described in an attempt to create a better anatomical footprint and enhance biological healing. Button fixation is advantageous because it is less invasive and reduces the risk of soft tissue irritation compared to washer and screw fixation.

The technique preferred by the senior author

The senior author’s preferred technique is a double tunnel transtibial pullout repair with two simple sutures tied with a cortical button. Standard anterolateral (AL) and anteromedial (AM) parapatellar portals located immediately adjacent to the patellar tendon are performed with additional AM or AL portals as needed. A curette is used to decorate the planned root attachment on the tibial plateau. An ACL or meniscal root guide is used to place a cannulated sleeve drill pin into the posterior aspect of the footprint, followed by a second drill hole with the cannula approximately 5 mm anterior. Once the tunnel placements are properly secured, the drill pins are removed and two simple sutures, one anterior and one posterior, are passed into the meniscal root using a suture feeder through the anterior or posteromedial portal, depending on the device. The sutures are then withdrawn through the appropriate tunnels and tied over a button on the AM or AL side of the tibia

FAQ

What is a meniscus tear at the root?

A meniscus tear at the root refers to a tear that occurs at the point where one of the menisci (crescent-shaped cartilage) in the knee attaches to the tibia bone. It can significantly impact the stability and function of the knee joint.

What causes a meniscus tear at the root?

These tears can be caused by sudden twisting or rotational movements of the knee, traumatic injuries, degenerative changes with age, or even as a result of long-standing wear and tear on the meniscus

What are the symptoms of a meniscus tear at the root?

Common symptoms include pain, swelling, limited range of motion, difficulty fully straightening the knee, and a sensation of locking or catching when moving the knee. In some cases, people might experience instability or a feeling of the knee “giving way.”

How is a meniscus tear at the root diagnosed?

Diagnosis typically involves a combination of physical examination, where the doctor assesses your knee’s range of motion and stability, and imaging tests such as MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) to visualize the tear and its location.

What are the treatment options for a meniscus tear at the root?

Treatment depends on the severity of the tear, your age, activity level, and overall health. Options include:

Conservative management: Rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE), along with physical therapy to improve strength and flexibility.

Medications: Anti-inflammatory drugs and over-the-counter painkillers can help control pain and inflammation.

Injections: Corticosteroid injections can provide temporary relief from pain and inflammation.

Surgery: For severe tears or tears that do not respond to conservative treatments, arthroscopic surgery might be necessary to either repair or trim the torn meniscus.How long does recovery take after treatment?

Recovery time varies depending on the severity of the tear and the treatment chosen. Conservative treatments might take several weeks to a few months, while recovery after surgery can range from a few weeks to a few months, depending on the procedure and rehabilitation process.

Can a meniscus tear at the root heal on its own?

Meniscus tears at the root typically have limited blood supply in that area, making it less likely for them to heal on their own. Surgical intervention might be required to achieve proper healing and restore knee function.

Can meniscus tears at the root lead to long-term complications?

If left untreated, meniscus tears can potentially lead to chronic knee pain, limited mobility, and an increased risk of developing osteoarthritis in the affected knee joint.

How can a meniscus tear at the root be prevented?

While some meniscus tears are the result of accidents, you can reduce the risk by maintaining strong leg muscles through regular exercise, using proper techniques during sports or physical activities, and avoiding sudden, forceful twisting motions.