Giant cell arteritis

Table of Contents

What is Giant cell arteritis?

The terms “giant cell arteritis” & “temporal arteritis” are sometimes used interchangeably, because of the often involvement of the temporal artery. Nevertheless, other big vessels such as the aorta can be involved.

Giant cell arteritis is also known as cranial arteritis & Horton’s disease. The name giant cell arteritis reflects the kind of inflammatory cell involved.

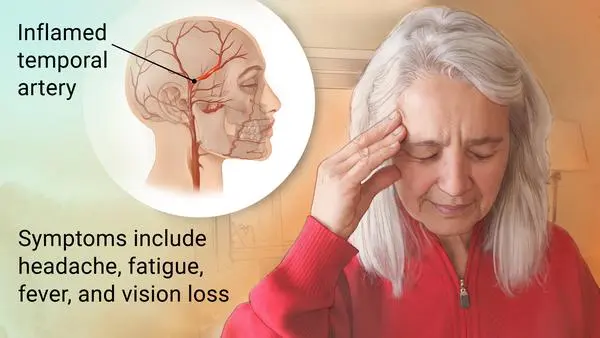

Giant cell arteritis (GCA), is an inflammatory autoimmune condition of large blood vessels. Symptoms might involve headache, pain over the temples, flu-like symptoms, double vision, & difficulty opening the mouth. The complication can involve blockage of the artery to the eye with resulting blindness, as well as aortic dissection, & aortic aneurysm. Giant cell arteritis is often related to polymyalgia rheumatica.

Giant cell arteritis is explained as an inflammation of the lining of the arteries. Most frequently, it affects the arteries in the head & neck, especially those in the temples. Giant cell arteritis often causes headaches, scalp tenderness, jaw pain, & vision problems. Untreated, it can lead to blindness.

This condition is treatable, commonly with steroid tablets. But if it’s left untreated it can be very severe & cause strokes or blindness.

Giant cell arteritis is one of a group of conditions of vasculitis. The term vasculitis means inflammation in blood vessels. There are various types of vasculitis because different blood vessels can be affected.

In temporal arteritis, known as giant cell arteritis or Horton’s arteritis, the temporal arteries, which supply blood from the heart to the scalp, are inflamed (swollen) & constricted (narrowed). The vasculitis that causes temporal arteritis can include other blood vessels, such as the posterior ciliary arteries (leading to blindness), or large blood vessels like the aorta & its branches, which can also cause serious health problems.

If not diagnosed & treated promptly, temporal arteritis can cause:

Damage to eyesight involves sudden blindness in one or both eyes. Damage to blood vessels, such as an aneurysm (a ballooning blood vessel that might burst). Other disorders include stroke or transient ischemic attacks (“mini-strokes”).

The cause is unknown. The underlying mechanism involves inflammation of the small blood vessels that supply the walls of big arteries. This mainly affects arteries around the head & neck, though some in the chest might also be affected. Diagnosis is suspected based on symptoms, blood tests, & medical imaging, & confirmed by a biopsy of the temporal artery. Nevertheless, in about 10% of people, the temporal artery is normal.

Giant cell arteritis can overlap with polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR). At some point, 5 – 15% of patients with polymyalgia rheumatica will have a diagnosis of GCA. About 50 % of patients with Giant cell arteritis have symptoms of polymyalgia rheumatica. The two conditions might occur at the same time or on their own. It also affects the same types of patients as polymyalgia rheumatica. It occurs only in adults, commonly over age 50, in women more than men, & in whites more than non-whites.

Treatment is significant with high doses of steroids such as prednisone or prednisolone. Once symptoms have resolved, the dose is decreased by about 15 percent per month. Once a low dose is reached, the taper is gradual further over the subsequent year. Other medications that might be recommended include bisphosphonates to prevent bone loss & a proton-pump inhibitor to prevent stomach problems.

What are the causes of Giant cell arteritis?

The underlying etiology of Giant cell arteritis is complex & has been widely researched, yet is still not well understood. This involves genetic & possibly infectious factors, which go on to trigger an immune response.

A genetic predisposition for Giant cell arteritis has been suspected, because of increased reports of Giant cell arteritis among first-degree relatives & rare familial forms of Giant cell arteritis. There have been reports of monozygotic twin concordance. further increasing this suspicion. Certain genes within the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I & class II regions, specifically, HLA DRB1*04, DRW6, & DR3 have been associated with increased susceptibility to Giant cell arteritis as well. These genes encode amino acids in the antigen-binding pocket of the HLA molecule, which suggests that the disease might be antigen-driven & further highlights the role of adaptive immunity in pathogenesis.

Other linked genes are those related to cytokine & chemokine expression, which can alter the clinical presentation of Giant cell arteritis in different patients. For example, polymorphisms at the tumor necrosis factor-a (TNF-a) locus & the interleukin (IL)-10 promoter region have independently correlated to a greater risk of developing Giant cell arteritis. Similarly so, genes encoding vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), interferon-c, & platelet glycoprotein receptor (PGR) are linked to an increased risk of ischemic complications in Giant cell arteritis.

In addition to genetic factors, an infectious or environmental factor has been suspected because of successive studies of a stable population in Minnesota, where a cyclic fluctuation in the incidence of Giant cell arteritis was noted. A range of infectious stimuli has been implicated, including Chlamydia pneumonia, varicella virus, and parvovirus B19. Nevertheless, there are conflicting reports that argue against these infectious stimuli in selective patients. Additionally, some have advocated that an endogenous element in the arterial wall stimulates the initial inflammatory event. Furthermore, the age-specific expression of Giant cell arteritis may be explained by age-related calcifications in the lamina, elastin, & extracellular matrix proteins.

After the starting trigger, regardless of etiology, a dual immune response begins. One includes a systemic inflammatory reaction & the other is a maladaptive, antigen-specific immune response. The systemic inflammatory reaction outcomes from the over-activation of the innate acute phase response: a non-antigen-driven, non-adaptive defense mechanism to overall stress & injury. This response is mediated by IL-6, produced by circulating macrophages, neutrophils, & monocytes. IL-6 levels have correlated with the intensity of the immune response & other acute phase reactants such as C-reactive protein, haptoglobin, fibrinogen, & complement. The combination of these reactants under the systemic inflammatory reaction leads to the general signs of inflammation seen in Giant cell arteritis such as fevers, chills, sweats, myalgias, anorexia, & weight loss. In comparison, the antigen-specific immune response damages the arterial walls & results in focal ischemic complications seen in Giant cell arteritis. The combination of these two processes outcomes in systemic inflammatory syndrome, & arteritis, respectively.

Giant cell arteritis preferentially affects three-layered vessels. These layers include an outer adventitia, a muscular medial layer, & an elastic lamina separating the inner intimal layer. The primary area of injury is in the adventitial layer. This is because of the fact that the adventitial layer is the only vascularized layer – composed of the vasa vasorum. Macrophages & T cells then use the vasa vasorum to enter the arterial wall. The luminal side is not usually affected because cell adhesion & entry is prohibited by the high velocity of blood flow through these arteries.

Activated T-cells in the vasa vasorum of medium & large vessels up-regulate & activate macrophages, which then form a granulomatous immune reaction. Activated T-cells lead the maturation of dendritic cells in the adventitia of the arteries, which produce chemokines that trigger the recruitment of CD4+ T cells. These CD4+ T cells then become activated, multiply & polarize to Th1 & Th17 cells, which in turn produce IFN-γ & IL-17 respectively. In response to IFN-γ release, endothelial cells & smooth muscle cells produce chemokines which lead to the recruitment of Th1 cells, CD8+ T cells, & monocytes. The monocytes distinguish into macrophages, which form giant cells, the histological trademark of Giant cell arteritis. This outcome in the destruction & remodeling of the arterial wall & progressive occlusion of the lumen is responsible for the ischemic symptoms of Giant cell arteritis.

Metalloproteinases & reactive oxygen intermediates expressed by macrophages ultimately cause destruction within the blood vessel wall. After this initial immune response, the vessel undergoes a healing response to injury, which includes intimal thickening, myofibroblast proliferation, & extracellular matrix deposition – all of which contribute to vascular stenosis & occlusion. This vascular stenosis & occlusion ultimately cause variable signs & symptoms, depending on the territory supplied by the affected vessel. For example, short posterior ciliary artery occlusion outcomes in ischemic optic neuropathy. Of note, there has been no proof demonstrating the role of B cells in the development of Giant cell arteritis. This is an important differentiating point between large vessel vasculitides & ANCA-associated vasculitides.

What are the symptoms of Giant cell arteritis?

Although non-specific, almost all patients with giant cell arteritis have one or more constitutional symptoms of weight loss, fever, fatigue, anorexia, and malaise, which are the most usual symptoms of Giant cell arteritis. Fever is generally low-grade & is present in up to 40 % of Giant cell arteritis patients at presentation. Further, Giant cell arteritis accounts for more than 15 % of all fevers of unknown origin in patients 65 years of age & older.

- Headache

New-onset headaches or a change in baseline headaches in geriatric patients shall always raise a concern about the possibility of Giant cell arteritis. Nevertheless, headaches might be absent in patients with isolated extra-cranial large vessel involvement, accounting for 10 to 15% of Giant cell arteritis. More than 75% of patients with Giant cell arteritis have headaches as a symptom, which is usually temporal but can be occipital, periorbital, or non-focal as well. Headaches have an insidious onset & slowly progress over time, although they might spontaneously resolve rarely, even with no treatment. The intensity & quality of headaches vary, & headaches can be severe & not respond to typical over-the-counter analgesic drugs. Scalp tenderness while combing or brushing hair is frequent & can be focal in the temporal areas or diffuse. In rare & severe cases, scalp necrosis can be present.

- Jaw Claudication

Jaw claudication or pain & discomfort while chewing or talking because of decreased blood supply to jaw muscles is a rather specific symptom of Giant cell arteritis and is seen in more than 30% of patients with Giant cell arteritis. Jaw claudication carries a more positive likelihood ratio for a positive temporal artery biopsy. Severe compromise in blood flow can cause tongue necrosis which is rarely seen.

- Temporal Artery Abnormality

Enlargement, nodular swelling, tenderness, & loss of pulse of the temporal artery, either unilateral or bilateral, are seen in up to 50 % of patients with Giant cell arteritis. Temporal artery nodularity also carries a more positive likelihood ratio for a positive temporal artery biopsy.

- Visual Symptoms

Visual complications are seen in up to 15 % of patients with Giant cell arteritis &, most commonly, are due to anterior ischemic optic neuropathy caused by vasculitis including the ophthalmic artery or the posterior ciliary arteries (although can be because of ischemia anywhere in the optic pathway). Patients might start having transient vision loss or amaurosis fugax. Vision loss is usually sudden & painless. It can start unilateral or bilateral, and there is a high risk of bilateral vision loss if unilateral vision loss is not quickly treated with high-dose corticosteroids. Vision loss can be partial or complete& is irreversible. Fundoscopy in starting reveals pallor & edema of the disc &, eventually, optic atrophy. Diplopia can also be seen in Giant cell arteritis due to oculomotor nerve palsy due to ischemia usually precedes vision loss.

- Polymyalgia Rheumatica (PMR)

Both polymyalgia rheumatica and Giant cell arteritis share similar pathogenesis. polymyalgia rheumatica is characterized by synovitis & periarthritis including the shoulder & hip girdles, leading to pain, stiffness, & loss of range of motion of the bilateral shoulder & hip girdles. polymyalgia rheumatica can occur before, with, or after Giant cell arteritis. Further, 40 to 60% of Giant cell arteritis patients have polymyalgia rheumatica, & 15 to 20% of PMR patients have Giant cell arteritis.

- Neurological Symptoms

Up to 30% of Giant cell arteritis patients experience neurological symptoms. Transient ischemia or strokes, especially including the posterior circulation can be seen in Giant cell arteritis. Mononeuropathies or peripheral neuropathies can also be seen in, especially C5 nerve root involvement, leading to a loss of shoulder abduction. Notably, Giant cell arteritis does not affect intra-cerebral arteries.

- Respiratory Symptoms

Up to 10% of patients with Giant cell arteritis experience dry or a productive cough (w or without sputum), sore throat, or hoarseness of voice. Throat pain can also occur because of pharyngeal ischemia.

- Extracranial Symptoms

10-15% of cases of Giant cell arteritis have extracranial involvement, including the thoracic or abdominal aorta & its branches, including the carotid, subclavian, axillary, & brachial arteries. Lower extremity arterial inclusion is less common. Extracranial involvement might happen in association with cranial involvement or even in the absence of cranial involvement. Up to 50% of these patients do not have typical cranial symptoms & have a negative temporal artery biopsy. Involvement is generally unilateral but can be bilateral. Starting symptoms are upper extremity claudication, bruits, lack of pulses in upper extremities, asymmetric pulse & blood pressure readings in upper extremities, & Raynaud’s phenomenon with or without digital ischemia or gangrene. Eventually, aortic aneurysms, thoracic, more commonly than abdominal aortic aneurysms, might form, although dissection is rare.

What are the risk factors of Giant cell arteritis?

Several factors can elevate the risk of developing giant cell arteritis, including:

- Age. Giant cell arteritis affects adults only, & rarely those under 50. Most patients with this condition develop signs & symptoms between the ages of 70 & 80.

- Sex. Women are about two times more prone to develop the condition than men.

- Race & geographic region. Giant cell arteritis is most usual among white people in Northern European populations or of Scandinavian descent.

- Polymyalgia rheumatica. Having polymyalgia rheumatica puts the patient at increased risk of developing giant cell arteritis.

- Family history. Sometimes the condition runs in families.

What are the complications of Giant cell arteritis?

Giant cell arteritis can cause severe complications, including:

- Blindness. Diminished blood flow to the eyes can cause sudden, painless vision loss in one or, rarely, in both eyes. Loss of vision is usually permanent.

- Aortic aneurysm. An aneurysm is a bulge that forms in a weakened blood vessel, usually in the large artery that runs down the center of the chest & abdomen (aorta). An aortic aneurysm may burst, causing life-threatening internal bleeding.

- cerebrovascular events in the vertebrobasilar distribution /Stroke. This is an uncommon complication of giant cell arteritis.

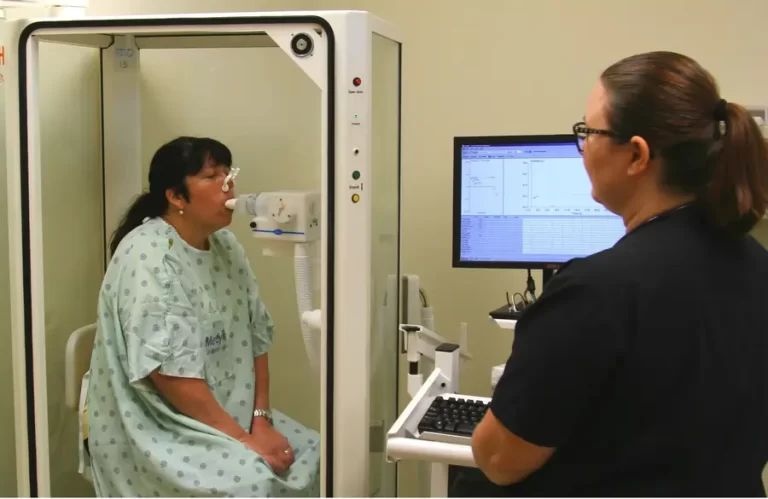

- Because this complication can occur even years after the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis, doctors might monitor your aorta with annual chest X-rays or other imaging tests, such as ultrasound & CT.

What is the prevalence of Giant cell arteritis?

It affects about 1 in 15,000 people over the age of 50 per year. The condition mostly occurs in those over the age of 50, being most usually among those in their 70s. Females are more frequently affected than males. Those of northern European descent are more usually affected. Life expectancy is typically normal. The first description of the disease occurred in 1890.

What is the differential diagnosis of Giant cell arteritis?

There can be several non-vasculitic conditions associated with unilateral or bilateral vision loss. In the elderly population, atherosclerosis & thromboembolism have to be considered. Infections such as bacterial endocarditis, tuberculosis, & human immunodeficiency virus can mimic symptoms & laboratory findings of Giant cell arteritis.

Malignancies such as lymphoma & myeloma can be associated with constitutional symptoms, arthralgia, & elevated acute-phase reactants. Other vasculitis disorders, especially ANCA-associated vasculitis, can be differentiated by the absence of fibrinoid necrosis on temporal artery biopsy & lack of serological markers in Giant cell arteritis. Finally, amyloidosis shall be considered as it can also cause jaw claudication, & congo-red staining of the biopsy can help diagnose amyloidosis.

What are the associated conditions of Giant cell arteritis?

The varicella-zoster virus antigen was found in 74% of temporal artery biopsies that were Giant cell arteritis-positive, suggesting that the VZV infection might trigger the inflammatory cascade.

The disorder might co-exists (in about half of cases) with polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR), which is characterized by sudden onset of pain & stiffness in muscles (pelvis, shoulder) of the body & is seen in the elderly. Giant cell arteritis & polymyalgia rheumatica are so closely linked that they are frequently considered to be different manifestations of the same disease process. polymyalgia rheumatica usually lacks cranial symptoms, including headache, pain in the jaw while chewing, & vision symptoms, that are present in Giant cell arteritis.

Giant cell arteritis can affect the aorta & lead to aortic aneurysm & aortic dissection. Up to 67% of people with Giant cell arteritis have evidence of an inflamed aorta, which can increase the risk of aortic aneurysm & dissection. There are arguments for the routine screening of each person with Giant cell arteritis for this possible life-threatening complication by imaging the aorta. Screening should be done on a case-by-case basis based on the signs & symptoms of people with Giant cell arteritis.

What is the diagnostic procedure for Giant cell arteritis?

The diagnosis of Giant cell arteritis should be considered in any patient over the age of 50 with new headaches, acute visual changes, symptoms of polymyalgia rheumatica, unexplained constitutional symptoms, or jaw claudication. Since individual patients with Giant cell arteritis can present with a wide range of symptoms & examination findings, & many of the symptoms may be transient, patients must be questioned directly about symptoms of Giant cell arteritis. In any patient in whom Giant cell arteritis is suspected based on history, examination findings, or an elevated ESR, C-reactive protein, or thrombocytosis, a temporal artery biopsy & initiation of corticosteroid treatment should be considered. In addition, several ancillary tests might help to confirm the diagnosis.

Although mathematical prediction models for Giant cell arteritis do not substitute for clinical experience, they can objectively guide shared doctor-patient decision-making. A ten-factor diagnostic pretest prediction model for Giant cell arteritis with geographic external validation & compliance with transparent reporting guidelines is available. There are accompanying posttest probability tables after the outcome of either ultrasound, MRI, or a negative temporal artery biopsy.

Diagnostic procedures:

Temporal artery biopsy

Unfortunately, there is no single test that is positive in all cases of Giant cell arteritis. A temporal artery biopsy is a gold standard; nevertheless, a negative biopsy does not confirm a negative diagnosis. The biopsy should be done as soon as possible after the patient’s presentation, but should not delay the starting of treatment with corticosteroids. The sensitivity of the biopsy is not typically affected for the first 2 weeks after starting therapy. Nevertheless, there has been one study that demonstrated a decrease in sensitivity from 82% to 60% after 1 week of steroid therapy.

False negatives are relatively common (5-13%) because of “skip lesions”, or areas without disease within the vessels. In order to avoid false negatives, it has been recommended that the biopsy sample have a length of 1 cm to up to 2.5 cm of the artery. In general, longer biopsy specimens have led to elevated chances of positive results. But more contemporary studies have challenged this belief, showing that shorter biopsy lengths might be adequate. Nevertheless, it is also important to note that shrinkage of the specimen will occur with fixation & should be taken into account. Approximately 10 % shrinkage can be expected on average.

Initial negative biopsy results might warrant follow-up with a contralateral biopsy depending on the clinical context. Physicians should assess the overall clinical picture including any additional imaging studies available before making this decision. Studies have demonstrated that repeat biopsy might be positive in 1-15% of patients.

All sections should be stained with hematoxylin & eosin. Furthermore, staining for elastin utilizing an elastic Van Gieson stain has been proposed in order to identify the internal elastic lamina. Nevertheless, a 2010 retrospective case series studying 105 biopsies showed no increase in diagnostic sensitivity using this method. Van Gieson staining might be helpful in cases of supplementary investigation, such as repeated biopsy.

Most commonly, a panarteritis consisting of lymphocytes & macrophages with or without granuloma formation is seen during the inspection. Additionally, intimal thickening & fragmentation of the internal elastic lamina should be sought. The procedure for obtaining a temporal artery biopsy is relatively safe, with rare reports of complications including hematoma, infection, nerve damage, stroke, & scalp necrosis.

Initial intraoperative appearance of a temporal artery biopsy. The ruler along the left side is situated posteriorly in this case. The incision is done posterior to the hairline (hair shaved) to avoid damage to the temporalis branch of the facial nerve. The right superficial temporal artery is clearly seen prior to complete dissection & biopsy. Except for miserably visible age-related calcification, the intraoperative appearance of the vessel was otherwise normal. The histopathology confirmed a negative result.

Ancillary imaging tests

Patients with Giant cell arteritis have abnormalities on several ancillary tests. Fluorescein angiography has been found to show delayed choroidal & central retinal artery filling, with possible choroidal non-perfusion, especially in the peri-papillary area. Angiographic findings are generally seen within the first days of symptom onset.

Color Doppler ultrasound (CDUS) has been earning popularity as an alternative to temporal artery biopsy. CDUS provides many advantages such as being non-invasive, safe & providing real-time imaging & analysis in addition to visualizing multiple arteries including the facial, occipital, & vertebral arteries. Ultrasonography might demonstrate arterial edema, which is represented by hypoechoic halos immediately adjacent to the arterial wall; This finding has been shown to have a sensitivity of 69% & specificity of 82% in a recent meta-analysis. In a single study, the specificity reached 100 percent when the halos were found bilaterally. Furthermore, CDUS is largely operator-dependent & lack of experience & standardization of image acquisition can hinder its potential assistance in diagnosis.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has recently been utilized in the diagnosis of Giant cell arteritis but might demonstrate blood vessel wall thickening & enhancement (in the same area as the “halo sign” on ultrasound). Comparing MRI results with clinically diagnosed Giant cell arteritis by meta-analysis demonstrated a pooled sensitivity & specificity of 73% & 83% respectively. Similarly so, in comparison to a positive temporal artery biopsy, the sensitivity and specificity were 9% & 81%, respectively. Limitations to this procedure include cost, radiation exposure, & diminishing sensitivity after initiation of glucocorticoid therapy.

Ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) has also been used preliminarily to find the halo sign. Finally, computerized tomography (CT), MRI, & PET scanning of the abdomen & chest might be useful to evaluate the aorta and other great vessels if large-vessel vasculitis is suspected.

Patients with a negative initial assessment via biopsy or ultrasound who continue to raise high clinical suspicion might warrant additional testing. Reasons for negative evaluation might include incorrect biopsy location, non-cranial artery involving Giant cell arteritis, or no Giant cell arteritis. Physicians might opt to evaluate patients for potential large-vessel Giant cell arteritis using imaging studies such as CDUS, CT, & MRI of the vascular system.

Comparison of different diagnostic imaging modalities

There is a lack of substantial data straightly comparing the different imaging modalities. Moreover, a benchmark for comparison is lacking since histological confirmation is not always there. In one cohort of 24 patients with suspected Giant cell arteritis, PET or CT was shown to be superior to CTA with a specificity of 100% vs 84.7% & comparable sensitivities of 66.7% vs 73.3% respectively. A different study in a temporal artery biopsy-positive cohort, with 15 Giant cell arteritis patients & 9 non-Giant cell arteritis patients, compared PET vs. CT-A. PET was a bit superior to CTA because of false positive findings with CTA, which effectively lowered the positive predictive value in that group. Other studies also found comparable outcomes of PET or CT & CTA, with a slightly better performance of PET or CT, as it was more sensitive in detecting inflammation in a given segment. In summary, PET or CT slightly outperforms CTA for initial Giant cell arteritis diagnosis, but the two techniques show good concordance.

Laboratory tests

The most usually utilized laboratory test in the diagnosis of Giant cell arteritis is the ESR, measured by the Westergren method. The ESR can occasionally be normal (ie. 100 mm/hr had a positive likelihood ratio (LR) of 2.466 & a negative LR of 0.775. Nevertheless, the ESR can be normalized by corticosteroids or immunosuppression, & there is frequently difficulty in decision-making when the ESR ranges between 50 & 100. In addition, the ESR might be elevated in other disease states such as anemia, inflammatory disease, malignancy, or infection. Therefore, the ESR must be interpreted in the clinical context of a given scenario.

The C-reactive protein (CRP) has been used as an adjunct test to the ESR. The CRP has certain benefits over the ESR, including a lack of variation with age, sex, or hematological factors. The sensitivity & specificity of the CRP for the diagnosis of Giant cell arteritis has been reported as 100% & 97%, respectively. Some authors have asserted that CRP is more sensitive in the evaluation of Giant cell arteritis. A retrospective chart review of 119 patients with biopsy-proven Giant cell arteritis demonstrated a 99% sensitivity when ESR & CRP were utilized together.

Platelets are also an acute phase reactant. Numerous studies have shown the use of platelets as a predictor of Giant cell arteritis. Anti-cardiolipin antibodies, elevated IFN gamma, & elevated interleukin-6. have not been proven to have a definite correlation with Giant cell arteritis in large studies, & are thus subjects for future research.

criteria

The 1990 American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for Giant cell arteritis involve the presence of at least 3 of the following 5 findings:

- Greater than 50 years old

- New onset of headache

- Temporal artery abnormality on examination

- Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) using the Westergreen method (>50 mm/h)

- Abnormal arterial biopsy demonstrating a necrotizing vasculitis with a predominance of mononuclear cells & granulomatous inflammation.

These criteria have been shown to have a sensitivity of 93.5% & a specificity of 91.2% in Giant cell arteritis in classifying patients with vasculitis. Nevertheless, the importance of the clinical history & setting cannot be understated when diagnosing Giant cell arteritis. Furthermore, these criteria were determined by rheumatologists, & studies that defined them were likely subject to the under-representation of patients with solely ocular manifestations. Several criticisms have been raised regarding this criterion, including the lack of specificity of headache, the lack of inclusion of several very significant markers such as CRP, jaw claudication, & neck pain, and the possibility of Giant cell arteritis with a normal ESR or temporal artery biopsy. A retrospective chart review of all patients undergoing biopsy at a single institution showed that 9 out of 35 patients with positive biopsies wouldn’t have been diagnosed with Giant cell arteritis using the 1990 guidelines. Furthermore, 11 out of 39 patients with negative biopsies met the criteria & would have been diagnosed with Giant cell arteritis.

What is the treatment plan for Giant cell arteritis?

Medical treatment for Giant cell arteritis:

Steroid tablets-

While there’s currently no cure for Giant cell arteritis, treatment with steroid tablets is very effective & usually starts to work within a few days. Prednisolone is the most usually used steroid tablet.

Steroid tablets decrease the activity of the immune system & reduce inflammation in blood vessels.

Because there’s a risk of sight loss or a stroke if Giant cell arteritis is not treated, it’s important to initiate steroid treatment straight away. If the doctor suspects you have Giant cell arteritis, they might prescribe a high dose of steroids before the diagnosis is confirmed.

To treat Giant cell arteritis, you’ll usually be given between 40 mg & 60 mg of steroid tablets every day, to begin with. This dose is generally continued for three to four weeks.

If patients are well after that, & your blood tests show that their condition has improved, the doctor will start reducing the dose. During this phase, a specialist will want to see the patient regularly to check how you’re getting on.

If a patient develops visual symptoms, or pain in her jaw or tongue when eating, you might need to go to the hospital urgently to be given steroids through a drip into a vein.

Usually, it takes one – three years to come off steroids altogether. For most of this time, the patient will be on a low dose. It isn’t always possible to stop taking steroids completely & some patients will need to be on a low dose for a long time or for all their life.

Patients shouldn’t stop taking their steroid tablets suddenly or alter the dose unless advised by their doctor, even if their symptoms have completely cleared up. This is because the body stops producing its own steroids, called cortisol, while you’re taking steroid tablets & needs some time to resume normal production of natural steroids when the medicine is reduced or stopped.

If the inflammation in the blood vessels returns this is called a relapse, & your steroid dose might have to be increased to deal with this. Relapse is most usual within the first 18 months of treatment.

What are the side effects of steroid treatment?

As with many drugs, there are various possible side effects from steroid treatment. Nevertheless, Giant cell arteritis is potentially a very serious condition. The benefits of taking steroids for someone with Giant cell arteritis, & therefore successfully treating their condition, far outweigh the risks of taking steroid tablets.

The initial high dose of steroid tablets to get the condition under control, & then the continued low dose to keep it at bay can sometimes cause the following side effects:

- changes in facial & body appearance

- facial flushing

- lack of sleep

- indigestion or stomach pain

- some weight gain

- dizziness or faintness

- difficulty concentrating

- mood changes.

Drugs called proton pump inhibitors can decrease the risk of indigestion. They do this by decreasing the amount of acid produced naturally in the stomach.

If patients are on steroids for a long time, other side effects might include:

- osteoporosis – a condition that causes bones to thin & fracture more easily

- easy bruising, stretch marks & thinning of the skin

- muscle weakness

- cataracts – a condition that causes the lens of one or both eyes to have cloudy patches

- glaucoma – a condition that the optic nerve in the eye is damaged

- diabetes – a medical condition that makes blood sugar level to be too high

- high blood pressure.

patient’s regular check-ups will help to identify any side effects so that they can be treated promptly.

If the patient on steroids for longer than three months, you might need treatments to prevent thinning of the bones, including:

calcium & vitamin D supplements

bisphosphonates – drugs that reduce the loss of bone mass.

Because steroids reduce the activity of the immune system, patients might be more likely to develop infections, & they can be more serious. For example, chickenpox & shingles can be severe in patients taking steroids.

Contact a doctor if the patient has not had chickenpox, & you come into contact with someone who has either chickenpox or shingles, as you might need antiviral treatment.

Steroid cards-

If you’re on steroid treatment, the patient should always carry a steroid card that says what dose you’re on.

If a patient requires to see another doctor for any reason, such as if you need an operation or a hospital admission; or if you need to see a healthcare professional such as a dentist, the patient should tell them what dose of steroids you’re on, or show them your steroid card.

In the unlikely event that a patient has to be rushed to the hospital in an emergency, it’s important for doctors there to know they are on steroid treatment. Steroid treatment can affect the body’s response to an injury, & doctors will need to know you’re on steroids & give you appropriate treatment.

Steroid cards are available from most pharmacies.

Are any other drugs utilized to treat giant cell arteritis?

Steroids are the first-line treatment to get Giant cell arteritis under control & prevent any serious complications. At present, there is no alternative first-line treatment available.

There are times when a doctor might suggest an additional medication to help you decrease the dose of steroids, this might happen if:

- your symptoms come back, otherwise known as a relapse

- your symptoms don’t improve despite steroid treatment

- you require steroid treatment for a long time.

Alternative treatments might include conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), including:

- methotrexate-While one study showed the potential steroid-sparing efficacy of methotrexate in Giant cell arteritis, another study failed to reciprocate these results. The role of methotrexate in Giant cell arteritis is debatable, & with the advent of tocilizumab, methotrexate use is generally not recommended for Giant cell arteritis.

- leflunomide

- azathioprine

- mycophenolate mofetil.

These drugs reduce the immune system, which can be misfiring in patients who have autoimmune conditions.

There are also some newer drugs available, known as biological therapies. These drugs attack key cells within the immune system to stop them from causing inflammation.

Biologic treatment includes medications such as tocilizumab. Tocilizumab is utilized mainly to treat patients with relapsing large vessel vasculitis. It can also be prescribed if other treatments have not worked.

At times, clinical trials of possible new treatments are carried out, & you might be offered one of these new drugs as part of a scientific study. Before agreeing to take part in one of these trials, you should make sure you fully understand what it involves by talking to a doctor.

the doctor might suggest low-strength aspirin as it helps to protect against loss of vision in Giant cell arteritis. the patient needs to discuss this with their doctor to ensure it is safe for them to take aspirin.

Medical follow up

Once corticosteroid treatment is started, it is important to follow the patient closely to determine the response to therapy. Some have recommended following the ESR & CRP from every 3 days to weekly, depending on the severity & route of administration of the corticosteroids. Although symptomatic improvement might be reached within days of therapy initiation, the ESR can take several weeks to decrease. Once an effective dose of corticosteroid is reached, the treatment at this dose should be continued for a minimum of 4-6 weeks. Nevertheless, treatment courses typically last for 1 to 2 years, given the importance of a very slow steroid taper to avoid a relapse of Giant cell arteritis.

There is no consensus on how often patients should be seen after starting treatment. A 2019 article in the British Medical Journal recommended follow-ups in weeks 0, 1, 3, & 6, and then monthly follow-ups afterward for the first year. Physicians might choose to design their own follow-up schedules & should individualize management focusing on patient disease progression, symptoms, & complications. Each visit should screen for progressing Giant cell arteritis & PMR including cranial symptoms & ischemic symptoms. The adverse effects of steroids should also be monitored closely. Proper patient education & access to support should not be overlooked as Giant cell arteritis is a chronic condition.

Once the decision is made to taper the corticosteroids, it is usually decreased at a rate of 5-10 mg per month until a dose of 10-15 mg per day is reached, & then the taper is reduced by 1-5 mg per month. The patient should be followed closely for any relapse of symptoms, or increase in the Erythrocyte sedimentation rate or CRP. Relapses typically occur within the first 1.5 years, with a median time of approx 7 months; nevertheless, the active disease has been reported up to 9 years after initiating therapy.

Physical therapy treatment for Giant cell arteritis:

Physical Therapists should be aware of associated signs & symptoms and refer patients accordingly.

Prompt starting of treatment might prevent blindness & other ischemic-related consequences.

There are no current physical therapy treatment options for temporal arteritis & the best management described in the literature involves the use of corticosteroids.

The most important thing for physical therapists to be aware of are the clinical examination findings that are frequently associated with Giant cell arteritis. These include palpation of the temporal artery, auscultation of arteries including the subclavian & axillary, & bilateral blood pressure determination, looking for a predominant unilateral vascular stenosis.

Physical therapy can be incorporated as a valuable component of a therapeutic regimen for this patient group in order to decrease the risk of early functional impairment & severe disability

What is the prognosis of Giant cell arteritis?

The visual prognosis is highly dependent on the rapidity with which steroids are started, & the status of the patient’s vision upon presentation. If the patient has already had an ischemic event outcome in AAION or a CRAO, it is rare that vision will improve appreciably. Nevertheless, up to one-third of treated cases might demonstrate some small degree of improvement in acuity after treatment has been started.

In general, vision frequently stabilizes once steroids are started; nevertheless, if it deteriorates on steroid therapy, it tends to be within 5 days & is rare after 1 month. It has been suggested that 9-17% of patients might have a deterioration of their vision while on corticosteroids. Additionally, one small study suggested that approximately 9% of patients can progress to fellow eye involvement after therapy is started; in contrast, 20-62% of untreated patients might progress to this stage. If there is visual deterioration after treatment is initiated, the prognosis is grim, with 80% of patients progressing to light perception or no light perception in one small study. Features that are associated with a worse visual prognosis involve visual symptoms before the steroids are initiated, older age, fever, weight loss, antecedent transient visual loss, diplopia, & jaw claudication. In addition, studies have demonstrated a worse ocular prognosis in patients with a high concentration of hemoglobin & a lower ESR.

Patients with Giant cell arteritis might also be at increased risk for cardiovascular disease within the first year of diagnosis, including myocardial infarction from coronary artery vasculitis, aortic disease, & stroke. These patients also might experience complications from long-term steroid use. Finally, it has been suggested that Giant cell arteritis patients are at increased risk for malignancy, which has been observed in 7% of patients. Fortunately, despite all of these potential complications, the life expectancy of this population is not typically different than that of the general population.

For the majority of patients, who get prompt treatment, there is a full recovery. Symptomatic improvement occurs in 2 to 4 days following treatment. To avoid the adverse effects of corticosteroids, tapering is recommended after 4 to 6 weeks. Blindness from temporal arteritis is very rare nowadays. Nevertheless, the course of the disease does vary from patient to patient & might last 3 months to 5 years. The major problem with the treatment of temporal arteritis today is the morbidity associated with corticosteroids. Thus, nursing should be familiar with & monitor these adverse events & report them to the team if present. Individuals likely to need prolonged treatment with steroids include females, older age, & those with a higher baseline ESR. The prognosis is poor for untreated individuals; these individuals might have blindness, develop a stroke, or have an MI. Overall, about 1 to 3% of patients with temporal arteritis die from a stroke or an MI.

FAQ (frequently asked questions)

While there’s currently no cure for Giant cell arteritis, treatment with steroid tablets is very effective & usually starts to work within a few days. Prednisolone is the most commonly utilized steroid tablet. Steroid tablets slow down the activity of the immune system & decrease inflammation in blood vessels.

However, few previous reports have comprehensively explained long-term competing risks of death in Giant cell arteritis patients. The results of our study indicate that Giant cell arteritis patients have an increased risk of death because of circulatory diseases and infections, but a decreased risk of death because of cancer over time.

The main signs are: often, severe headaches. pain & tenderness over the temples. jaw pain while eating or talking. vision problems, such as loss of vision in one or both eyes or double vision.

We found that the diagnosis of Giant cell arteritis significantly affects the 5-year survival rate; but by 11.12 years the mortality rates of the groups converge, suggesting that the negative impact of Giant cell arteritis on survival is eventually lost.

Arteries most affected in giant cell arteritis are the temporal artery & other cranial arteries now called cranial-Giant cell arteritis, but inflammation of the aorta & other large arteries in the body can occur as well & might present differently now called large vessel-Giant cell arteritis.

3 Comments