Torticollis of the neck (Wryneck): Physiotherapy Treatment

Table of Contents

What is torticollis of the neck?

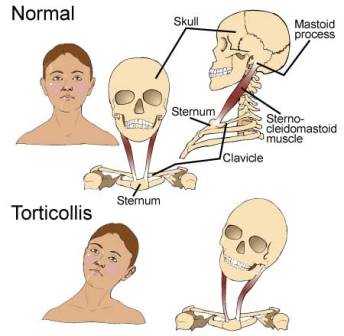

Torticollis of the neck, also known as wry neck, is a dystonic condition defined by an abnormal, asymmetrical head or neck position, which may be due to a variety of causes. The term torticollis is derived from the Latin words tortus for twisted and collum for neck.

The most common case has no obvious cause, and the pain and difficulty with turning the head usually go away after a few days, even without treatment.

If your baby has the condition at birth, it’s called congenital muscular torticollis. That’s the most common type.

Torticollis in babies can also develop the condition after birth. Then it’s called “acquired,” rather than congenital. Acquired torticollis may be linked to other, more serious medical issues.

Signs and symptoms:

Torticollis is a fixed or dynamic tilt, or rotation, with flexion or extension of the head and/or neck. The type of torticollis can be described depending on the positions of the head and neck.

- Laterocollis: the head is tipped toward the shoulder

- Rotational torticollis: the head rotates along the longitudinal axis

- Anterocollis: forward flexion of the head and neck

- Retrocollis: hyperextension of head and neck backward

A combination of these movements may often be observed. Torticollis can be a disorder in itself as well as a symptom in other conditions.

Other symptoms include:

- Neck pain

- Occasional formation of a mass

- Thickened or tight sternocleidomastoid muscle

- Tenderness on the cervical spine

- Tremor in head

- Unequal shoulder heights

- Decreased neck movement

What are the Causes of the Torticollis of the neck?

A multitude of conditions may lead to the development of torticollis including muscular fibrosis, congenital spine abnormalities, or toxic or traumatic brain injury. A rough categorization discerns between congenital torticollis and acquired torticollis.

Other categories include:

- Osseous

- Traumatic

- CNS/PNS

- Ocular

- Non-muscular soft tissue

- Spasmodic

- Drug-induced

- Congenital muscular torticollis

The congenital muscular torticollis is the most common torticollis which is present at birth. The cause of congenital muscular torticollis is unclear. Birth trauma or intrauterine malposition is considered to be the cause of damage to the sternocleidomastoid muscle in the neck. Other alterations to the muscle tissue arise from repetitive microtrauma within the womb or a sudden change in the calcium concentration in the body which causes a prolonged period of muscle contraction.

Any of these mechanisms can result in a shortening or excessive contraction of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, which curtails its range of motion in both rotation and lateral bending. The head typically is tilted in lateral bending toward the affected muscle and rotated toward the opposite side. In other words, the head itself is tilted in the direction towards the shortened muscle with the chin tilted in the opposite direction.

Congenital Torticollis:

Congenital Torticollis is presented at 1–4 weeks of age, and a hard mass usually develops. It is normally diagnosed using ultrasonography and a colour histogram or clinically by evaluating the infant’s passive cervical range of motion.

Congenital torticollis constitutes the majority of cases seen in clinical practice. The reported incidence of congenital torticollis is 0.3-2.0%. Sometimes a mass, such as a sternocleidomastoid tumor, is noted in the affected muscle at the age of two to four weeks. Gradually it disappears, usually by the age of eight months, but the muscle is left fibrotic.

Acquired torticollis:

Noncongenital muscular torticollis may result from scarring or disease of cervical vertebrae, adenitis, tonsillitis, rheumatism, enlarged cervical glands, retropharyngeal abscess, or cerebellar tumors. It may be spasmodic (clonic) or permanent (tonic). The latter type may be due to Pott’s Disease (tuberculosis of the spine).

A self-limiting spontaneously occurring form of torticollis with one or more painful neck muscles is by far the most common (‘stiff neck’) and will pass spontaneously in 1–4 weeks. Usually, the sternocleidomastoid muscle or the trapezius muscle is involved. Sometimes draughts, colds, or unusual postures are implicated; however, in many cases, no clear cause is found. These episodes are commonly seen by physicians.

Tumors of the skull base (posterior fossa tumors) can compress the nerve supply to the neck and cause torticollis, and these problems must be treated surgically.

Infections in the posterior pharynx can irritate the nerves supplying the neck muscles and cause torticollis, and these infections may be treated with antibiotics if they are not too severe, but could require surgical debridement in intractable cases.

Ear infections and surgical removal of the adenoids can cause an entity known as Grisel’s syndrome, a subluxation of the upper cervical joints, mostly the atlantoaxial joint, due to inflammatory laxity of the ligaments caused by an infection.

The use of certain drugs, such as antipsychotics, can cause torticollis.

Antiemetics – Neuroleptic Class – Phenothiazines

There are many other rare causes of torticollis. A very rare cause of acquired torticollis is fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP), the hallmark of which is malformed great toes.

Spasmodic torticollis:

Torticollis with recurrent, but transient contraction of the muscles of the neck and especially of the sternocleidomastoid, is called spasmodic torticollis. Synonyms are “intermittent torticollis”, “cervical dystonia” or “idiopathic cervical dystonia”, depending on the cause.

Trochlear torticollis:

Torticollis may be unrelated to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, instead caused by damage to the trochlear nerve (fourth cranial nerve), which supplies the superior oblique muscle of the eye. The superior oblique muscle is involved in depression, abduction, and intorsion of the eye. When the trochlear nerve is damaged, the eye is extorted because the superior oblique is not functioning.

The affected person will have vision problems unless they turn their head away from the side that is affected, causing intorsion of the eye and balancing out the extorsion of the eye. This can be diagnosed by the Bielschowsky test, also called the head-tilt test, where the head is turned to the affected side. A positive test occurs when the affected eye elevates, seeming to float up.

Anatomy of the Neck:

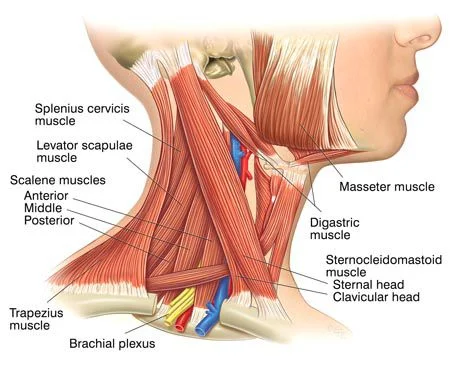

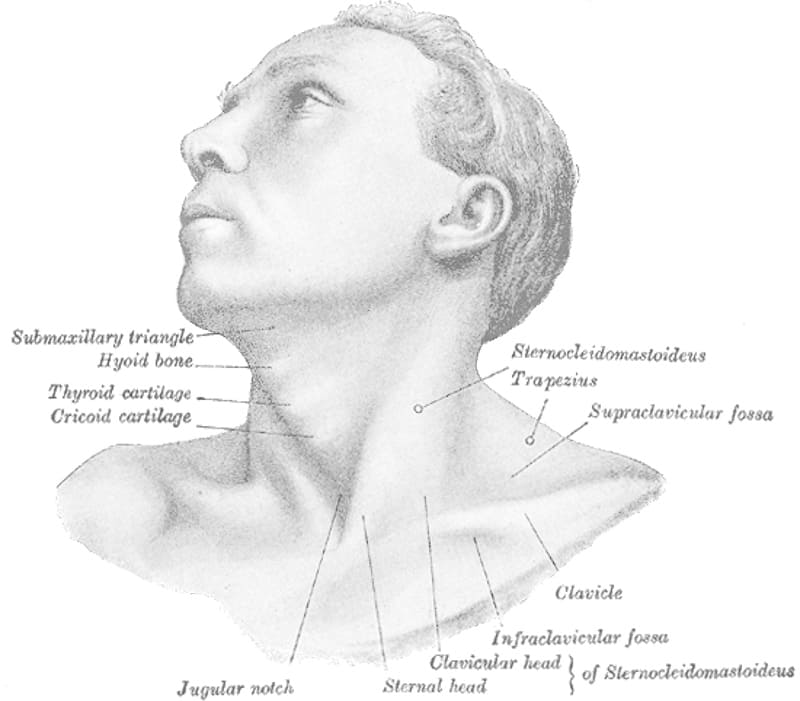

The underlying anatomical distortion causing torticollis is a shortened sternocleidomastoid muscle. This is the muscle of the neck that originates at the sternum and clavicle and inserts on the mastoid process of the temporal bone on the same side.

There are two sternocleidomastoid muscles in the human body and when they both contract, the neck is flexed. The main blood supply for these muscles comes from the occipital artery, superior thyroid artery, transverse scapular artery, and transverse cervical artery. The main innervation to these muscles is from cranial nerve XI (the accessory nerve) but the second, third, and fourth cervical nerves are also involved. pathologies in these blood and nerve supplies can lead to torticollis.

Diagnosis:

Evaluation of a child with torticollis starts with history taking to determine circumstances surrounding birth and any possibility of trauma or associated symptoms. Physical examination reveals decreased rotation and bending to the side opposite from the affected muscle.

Physical Evaluation should include a thorough neurologic examination, and the possibility of associated conditions such as developmental dysplasia of the hip and clubfoot should be examined.

Radiographs of the cervical spine should be obtained to rule out obvious bony abnormality, and MRI should be considered if there is concern about structural problems or other conditions.

Ultrasonography can be used to visualize muscle tissue, with a colour histogram generated to determine cross-sectional area and thickness of the muscle.

Evaluation by an optometrist or an ophthalmologist should be considered in children to ensure that the torticollis is not caused by vision problems (IV cranial nerve palsy, nystagmus-associated “null position,” etc.).

Differential Diagnosis:

- Cranial nerve IV palsy

- Spasmus nutans

- Sandifer syndrome

- Myasthenia gravis

- Cervical dystonia appearing in adulthood has been believed to be idiopathic in nature, as specific imaging techniques most often find no specific cause.

Treatment for torticollis:

Physiotherapies treatment such as stretching to release tightness, strengthening exercises to improve muscular balance, and handling to stimulate symmetry. A TOT collar is sometimes applied. Early initiation of treatment is very important for full recovery and to decrease the chance of relapse

Physiotherapy Treatment:

Physiotherapy is an option for treating torticollis in a non-invasive and cost-effective manner. While outpatient torticollis in babies physiotherapy is effective, Home therapy performed by a parent or guardian is just as effective in reversing the effects of congenital torticollis. It is important for physiotherapists to educate parents on the importance of their role in treatment and to create a home treatment plan together with them for the best results for their child.

Five components have been recognized as the “first choice intervention” in PT for the treatment of torticollis and include neck passive range of motion, neck, and trunk active range of motion, development of symmetrical movement, environmental adaptations, and caregiver education.

In therapy, parents or guardians should expect their child to be provided with these important components, explained in detail below. Lateral neck flexion and overall range of motion can be regained quicker in newborns when parents conduct physical therapy exercises several times a day.

Exercises for torticollis:

Stretching the neck and trunk muscles actively. Parents can help promote this stretching at home with infant positioning. For example, prone positioning will encourage the child to lift their chin off the ground, thereby strengthening their bilateral neck and spine extensor muscles, and stretching their neck flexor muscles.

Active rotation exercises in supine, sitting, or prone position by using toys, lights, and sounds to attract the infant’s attention to turn the neck and look toward the non-affected side.

Stretching the muscle in a prone position passively. Passive stretching is manual and does not include infant involvement. Two people can be involved in these stretches, one person stabilizing the infant while the other holds the head and slowly brings it through the available range of motion. Passive stretching should not be painful to the child and should be stopped if the child resists. Also, discontinue the stretch if changes in breathing or circulation are seen or felt.

Stretching the muscle in a lateral position supported by a pillow (have the infant lie on the side with the neck supported by a pillow). The affected side should be against the pillow to deviate the neck towards the non-affected side.

Environmental adaptations can control posture in strollers, car seats, and swings (using a U-shaped neck pillow or blankets to hold the neck in a neutral position).

Passive cervical rotation (much like stretching when being supported by a pillow, have affected side down)

Position infants in the crib with the affected side by the wall so they must turn to the non-affected side to face out.

Physiotherapists often encourage parents and caregivers of children with torticollis to modify the environment to improve neck movements and position.

These Modifications may include :

Adding neck supports to the car seat to attain optimal neck alignment

Reducing time spent in a single position

Using toys to encourage the child to look in the direction of limited neck movement

Alternating sides when bottle or breastfeeding

Encouraging prone playtime (tummy time). Although the Back to Sleep campaign promotes infants sleeping on their backs to avoid sudden infant death syndrome during sleep, parents should still ensure that their infants spend some waking hours on their stomachs.

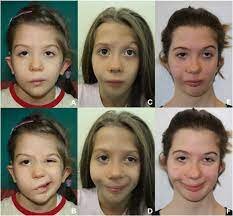

A development defect is one sternomastoid muscle or mal-position of the neck in the uterus, which can give rise to the deformity. The shortening of the sternomastoid is the principal causative factor. There may be an associated shortening of the scalenii, platysma, splenius, or trapezius muscles. Incidence is more common in girls, and the side affected is usually left. Occasionally, it may bilateral. The affected sternomastoid may get atrophied and facial asymmetry may occur in untreated cases.

Nature of the deformity :

The head is fixed inside flexion to the same side (i.e, on the side of the affected muscle) while it is rotated to the opposite side. The shoulder on the affected side is raised.

Scoliosis with convexity to the sound side may be present in the cervical region. Facial asymmetry with smaller eye and lowering of the corners of the mouth and eye with a deviation of the nose on the affected side may be present. In rare bilateral affections, both the sternomastoid are contracted. The head is protruded forward with associated kyphosis.

The basic objectives are :

- To correct the deformity by releasing the contracted soft tissues and

- To maintain the correction by suitable exercise regime; avoiding recurrence.

Early stages – mild cases :

Children with a mild degree of deformity reporting early for the treatment can be managed with physiotherapy.

The physiotherapy procedures are :

I. Evaluation: Careful evaluation of ROM and the degree of deformity.

II. Massage : Massage can relax the muscle preceding the stretching manoeuvres.

III. Hot Pack – Therapy Modality: Carefully administered thermo-therapy modality induces relaxation.

IV. Relax Passive movements : The child is placed in supine position with head beyond the edge of the table with the neck in extension by positioning a pillow under the thoracic region; Shoulders are stabilized by an assistant.

To attain relaxation, all the movements of the cervical spine are done in the form of slow relaxed passive movements.

This should be followed by sustained passive stretching to the affected sternomastoid. E.g. when the right sternomastoid is involved the head should be gradually bent inside flexion to the left, held there for a while and then rotated gradually to the right. Try to gain as much overcorrection as possible by applying gradual traction to gain further stretching.

Maintenance of Correction: Once the correction is achieved. It has to be maintained by passively holding or keeping a weight cuff.

The same manoeuvre can be repeated during the subsequent visits.

Active correction: Active correction is best achieved by assisting the child’s head to follow an object moved in the proper arc of correction. The bright-colored sound-producing object is ideal for attracting the child attention.

PNF: patients with neck extension can be used to advantage with emphasis on stretch and traction

Home treatment programme: This assumes an important role as these manipulations need to be repeated. The mother should be trained properly for this. The best method is to put the child in a prone and teach the mother to carefully move the head towards the affected side and the child is encouraged to look back over the right shoulder.

Positioning: Exact positioning of the head during sleep is important. The child should be made to sleep on the opposite side of the lesion and the position of the head adjusted by a pillow or sandbag in a maximally corrected posture during sleep.

This positioning has two advantages: First, there is natural relaxation of the muscle- Secondly, whatever correction is achieved, it is maintained for a longer period during sleep. However, the mother should intermittently check the correction.

Older children and adults: With advancing age the deformity gets organized and does not get corrected by conservative management.

Surgery:

Surgical treatment is The sterna and the clavicular heads of the sternomastoid are divided close to the origin along with the release of the tight fascia. The head is then immobilized in a plaster cast in an over-corrected position for 2 to 4 weeks. Mobilization begins as soon as the cast is removed.

6 Comments