DEVELOPMENTAL COORDINATION DISORDER

Table of Contents

Definition

Developmental coordination disorder is diagnosed when children do not develop normal motor coordination (coordination of movements involving the voluntary muscles).

What is a Developmental coordination disorder?

Developmental coordination disorder has been known by many other names, some of which are still used today. It has been called clumsy child syndrome, clumsiness, developmental disorder of motor function, and congenital maladroitness. Developmental coordination disorder is usually first recognized when a child fails to reach such normal developmental milestones as walking or beginning to dress him- or herself.

Children with developmental coordination disorder often have difficulty performing tasks that involve both large and small muscles, including forming letters when they write, throwing or catching balls, and buttoning buttons. Children who have developmental coordination disorder have often developed normally in all other ways. The disorder can, however, lead to social or academic problems for children. Because of their underdeveloped coordination, they may choose not to participate in activities on the playground. This avoidance can lead to conflicts with or rejection by their peers. Also, children who have problems forming letters when they write by hand, or drawing pictures, may become discouraged and give up academic or artistic pursuits even though they have normal intelligence.

Developmental coordination disorder (DCD) also known as developmental motor coordination disorder, developmental dyspraxia, or simply dyspraxia,Is a chronic neurological disorder beginning in childhood. It is also known to affect planning of movements and co-ordination as a result of brain messages not being accurately transmitted to the body. Impairments in skilled motor movements per a child’s chronological age interfere with activities of daily living. A diagnosis of DCD is then reached only in the absence of other neurological impairments like cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, multiple sclerosis, or Parkinson’s disease. According to CanChild in Canada, this disorder affects 5 to 6 percent of school-aged children. However, this disorder does progress towards adulthood, therefore making it a lifelong condition.

Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD) is a motor skills disorder that affects five to six percent of all school-aged children. The ratio of boys to girls varies from 2:1 to 5:1, depending on the group studied. DCD occurs when a delay in the development of motor skills, or difficulty coordinating movements, results in a child being unable to perform common, everyday tasks. By definition, children with DCD do not have an identifiable medical or neurological condition that explains their coordination problems.

While it was once thought that children with DCD would simply outgrow their motor difficulties, research tells us that DCD persists throughout adolescence into adulthood. Children with DCD can and do learn to perform certain motor tasks well, however, they have difficulty when faced with new, age-appropriate ones and are at risk for secondary difficulties that result from their motor challenges. Although there is currently no cure for DCD, early intervention and treatment may help to reduce the emotional, physical and social consequences that are often associated with this disorder.

Frequently described as “clumsy” or “awkward” by their parents and teachers, children with DCD have difficulty mastering simple motor activities, such as tying shoes or going down stairs, and are unable to perform age-appropriate academic and self-care tasks. Some children may experience difficulties in a variety of areas while others may have problems only with specific activities. For a list of some of the more common characteristics that may be observed in a child with DCD, click here. Children with DCD usually have normal or above average intellectual abilities. However, their motor coordination difficulties may impact their academic progress, social integration and emotional development.

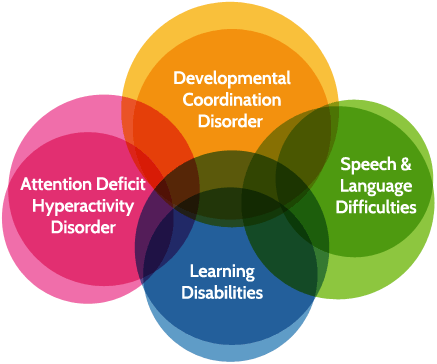

DCD is commonly associated with other developmental conditions, including attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), learning disabilities (LD), speech-language delays and emotional and behavioural problems. For more information on related developmental disorders and their co-occurrence with DCD.

DCD is difficult to diagnose because the symptoms may be confused with those of other conditions. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) lists four criteria that must be met for a diagnosis of DCD:

The child shows delays in reaching motor milestones.

The condition significantly interferes with activities of daily living and/or academic performance.

The symptoms begin early in the child’s life.

Difficulties with motor skills are not better explained by intellectual disability, visual impairment, or brain disorders.

Signs and symptoms of Developmental coordination disorder

Various areas of development can be affected by developmental coordination disorder and these will persist into adulthood, as DCD has no cure. Often various coping strategies are developed, and these can be enhanced through occupational therapy, psychomotor therapy, physiotherapy, speech therapy, or psychological training.

In addition to the physical impairments, developmental coordination disorder is associated with problems with memory, especially working memory. This typically results in difficulty remembering instructions, difficulty organizing one’s time and remembering deadlines, increased propensity to lose things or problems carrying out tasks which require remembering several steps in sequence (such as cooking). Whilst most of the general population experience these problems to some extent, they have a much more significant impact on the lives of dyspraxic people. However, many dyspraxics have excellent long-term memories, despite poor short-term memory. Many dyspraxics benefit from working in a structured environment, as repeating the same routine minimises difficulty with time-management and allows them to commit procedures to long-term memory.

People with developmental coordination disorder sometimes have difficulty moderating the amount of sensory information that their body is constantly sending them, so as a result dyspraxics are prone to sensory overload and panic attacks.

Moderate to extreme difficulty doing physical tasks is experienced by some dyspraxics, and fatigue is common because so much energy is expended trying to execute physical movements correctly. Some dyspraxics suffer from hypotonia, low muscle tone, which like DCD can detrimentally affect balance.

Signs of DCD can appear soon after birth. Newborns may have trouble learning how to suck and swallow milk. Toddlers may be slow to learn to roll over, sit, crawl, walk, and talk.

As you enter school, symptoms of the disorder may become more noticeable. Symptoms of DCD may include:

an unsteady walk

difficulty going down stairs

dropping objects

running into others

frequent tripping

difficulty tying shoes, putting on clothes, and other self-care activities

difficulty performing school activities such as writing, coloring, and using scissors

People with DCD may become self-conscious and withdraw from sports or social activities. However, limited exercise can lead to poor muscle tone and weight gain. Maintaining social involvement and good physical condition is essential for overcoming the challenges of DCD.

Gross motor control

Whole body movement and motor coordination issues mean that major developmental targets including walking, running, climbing and jumping can be affected. The difficulties vary from person to person and can include the following:

Poor timing

Poor balance(sometimes even falling over in mid-step). Tripping over one’s own feet is also common.

Difficulty combining movements into a controlled sequence.

Difficulty remembering the next movement in a sequence.

Problems with spatial awareness,or proprioception.

Trouble picking up and holding onto simple objects such as pencils, owing to poor muscle tone or proprioception.

Clumsiness to the point of knocking things over, causing minor injuries to oneself and bumping into people accidentally.

Difficulty in determining left from right.

Cross-laterality, ambidexterity, and a shift in the preferred hand are also common in people with developmental coordination disorder.

Problems with chewing foods.

Fine motor control

Fine-motor problems can cause difficulty with a wide variety of other tasks such as using a knife and fork, fastening buttons and shoelaces, cooking, brushing teeth, styling hair, shaving, applying cosmetics, opening jars and packets, locking and unlocking doors, and doing housework.

Difficulties with fine motor co-ordination lead to problems with handwriting,[3] which may be due to either ideational or ideo-motor difficulties.[non-primary source needed] Problems associated with this area may include:

Learning basic movement patterns.

Developing a desired writing speed.

Establishing the correct pencil grip.

The acquisition of graphemes – e.g. the letters of the Latin alphabet, as well as numbers.

Developmental verbal dyspraxia

Developmental verbal dyspraxia (DVD) is a type of ideational dyspraxia, causing speech and language impairments. This is the favoured term in the UK; however, it is also sometimes referred to as articulatory dyspraxia, and in the United States the usual term is childhood apraxia of speech (CAS).

Key problems include:

Difficulties controlling the speech organs.

Difficulties making speech sounds.

Difficulty sequencing sounds

Within a word, and

Forming words into sentences.

Difficulty controlling breathing, suppressing salivation and phonation when talking or singing with lyrics.

Slow language development.

Associated disorders and secondary consequences

People who have developmental coordination disorder may also have one or more of these co-morbid conditions:

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (inattention, hyperactivity, impulsive behaviour).

Autism spectrum disorder.

Dyscalculia (difficulty with numbers).

Dysgraphia (an inability to write neatly or draw).

Dyslexia (difficulty with reading and spelling).

Hypotonia (low muscle tone).

Sensory processing disorder.

Specific language impairment (SLI).

Visual perception deficits.

However, a person with DCD is unlikely to have all of these conditions. The pattern of difficulty varies widely from person to person; an area of major weakness for one dyspraxic can be an area of strength or gift for another. For example, while some dyspraxics have difficulty with reading and spelling due to dyslexia, or with numeracy due to dyscalculia, others may have brilliant reading and spelling or mathematical abilities. Some estimates show that up to 50% of dyspraxics have ADHD.

Sensory processing disorder

Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD) concerns having oversensitivity or undersensitivity to physical stimuli, such as touch, light, sound, and smell. This may manifest itself as an inability to tolerate certain textures such as sandpaper or certain fabrics such as wool, oral intolerance of excessively textured food (commonly known as picky eating), being touched by another individual (in the case of touch oversensitivity) or it may require the consistent use of sunglasses outdoors since sunlight may be intense enough to cause discomfort to a dyspraxic (in the case of light oversensitivity). An aversion to loud music and naturally loud environments (such as clubs and bars) is typical behavior of a dyspraxic individual who suffers from auditory oversensitivity, while only being comfortable in unusually warm or cold environments is typical of a dyspraxic with temperature oversensitivity. Undersensitivity to stimuli may also cause problems. Dyspraxics who are undersensitive to pain may injure themselves without realising it. Some dyspraxics may be oversensitive to some stimuli and undersensitive to others.

Specific language impairment

Specific Language Impairment (SLI) research has found that students with developmental coordination disorder and normal language skills still experience learning difficulties despite relative strengths in language. This means that for students with developmental coordination disorder their working memory abilities determine their learning difficulties. Any strength in language that they have is not able to sufficiently support their learning.

Students with developmental coordination disorder struggle most in visual-spatial memory. When compared to their peers who don’t have motor difficulties, students with developmental coordination disorder are seven times more likely than typically developing students to achieve very poor scores in visual-spatial memory. As a result of this working memory impairment, students with developmental coordination disorder have learning deficits as well.

Psychological and social consequences

Psychological domain: Children with DCD struggle with lower self-efficacy and lower self-perceived competence in peer and social relations. They demonstrate greater aggressiveness and hyperactivity.

Social domain: Children are more vulnerable to social rejection and bullying, along with higher levels of loneliness.

Diagnosis

Assessments for developmental coordination disorder typically require a developmental history,detailing ages at which significant developmental milestones, such as crawling and walking,occurred. Motor skills screening includes activities designed to indicate developmental coordination disorder, including balancing, physical sequencing, touch sensitivity, and variations on walking activities.

The criteria are as follows:

Motor Coordination will be greatly reduced, although the intelligence of the child is normal for the age.

The difficulties the child experiences with motor coordination or planning interfere with the child’s daily life.

The difficulties with coordination are not due to any other medical condition

If the child does also experience comorbidities such as intellectual or other developmental disability; motor coordination is still disproportionally affected.

Screening tests that can be used to assess developmental coordination disorder include:

Movement Assessment Battery for Children (Movement-ABC – Movement-ABC 2)[non-primary source needed][non-primary source needed][non-primary source needed]

Peabody Developmental Motor Scales- Second Edition (PDMS-2)

Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency (BOTMP-BOT-2)[non-primary source needed][non-primary source needed][54][non-primary source needed]

Motoriktest für vier- bis sechsjährige Kinder (MOT 4-6)[non-primary source needed]

Körperkoordinationtest für Kinder (KTK)

Test of Gross Motor Development, Second Edition (TGMD-2)

Maastrichtse Motoriek Test (MMT)

Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-IV)[citation needed]

Wechsler Individual Achievement Test (WAIT-II)[citation needed]

Test Of Word Reading Efficiency Second Edition (TOWRE-2)[citation needed]

Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire (DCD-Q)

Children’s Self-Perceptions of Adequacy in, and Predilection for Physical Activity (CSAPPA)[57]

Currently there is no single gold standard assessment test.

A baseline motor assessment establishes the starting point for developmental intervention programs. Comparing children to normal rates of development may help to establish areas of significant difficulty.

However, research in the British Journal of Special Education has shown that knowledge is severely limited in many who should be trained to recognise and respond to various difficulties, including developmental coordination disorder, dyslexia and deficits in attention, motor control and perception (DAMP).The earlier that difficulties are noted and timely assessments occur, the quicker intervention can begin. A teacher or GP could miss a diagnosis if they are only applying a cursory knowledge.

“Teachers will not be able to recognise or accommodate the child with learning difficulties in class if their knowledge is limited. Similarly GPs will find it difficult to detect and appropriately refer children with learning difficulties.”[non-primary source needed]

DCD is treated with a long-term program of education, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and social skills training to help you adapt to the disorder.

Physical education can help you develop coordination, balance, and better communication between your brain and your body. Individual sports such as swimming or bicycling may offer better opportunities to build motor skills than team sports. Daily exercise is essential if you have DCD, in order to train your body and brain to work together and to reduce your risk of obesity.

Occupational therapy can help you master daily activities. Occupational therapists know lots of techniques for helping people perform difficult tasks. Your occupational therapist can also work with school officials to identify changes that will help you to succeed in school, such using a computer instead of hand writing assignments.

Physiotherapy Treatments of Developmental coordination disorder

No treatments are known to work for all cases of developmental coordination disorder. Experts recommend that a specialized course of treatment, possibly involving work with an occupational therapist, be drawn up to address the needs of each child. Many children can be effectively helped in special education settings to work more intensively on such academic problems as letter formation. For other children, physical education classes designed to improve general motor coordination, with emphasis on skills the child can use in playing with peers, can be very successful. Any kind of physical training that allows the child to safely practice motor skills and motor control may be helpful.

It is important for children who have developmental coordination disorder to receive individualized therapy, because for many children the secondary problems that result from extreme clumsiness can be very distressing. Children who have developmental coordination disorder often have problems playing with their peers because of an inability to perform the physical movements involved in many games and sports. Unpopularity with peers or exclusion from their activities can lead to low self-esteem and poor self-image. Children may go to great lengths to avoid physical education classes and similar situations in which their motor coordination deficiencies might be noticeable. Treatments that focus on skills that are useful on the playground or in the gymnasium can help to alleviate or prevent these problems.

Children with developmental coordination disorder also frequently have problems writing letters and doing sums, or performing other motor activities required in the classroom— including coloring pictures, tracing designs, or making figures from modeling clay. These children may become frustrated by their inability to master tasks that their classmates find easy, and therefore may stop trying or become disruptive. Individualized programs designed to help children master writing or skills related to arts and crafts may help them regain confidence and interest in classroom activities.

The child’s physiotherapist will perform an evaluation that includes:

Taking a history, asking questions about the mother’s pregnancy and the child’s birth and developmental stages (the age the child sat up, crawled, walked, etc), the general health of the child, and the parents’ concerns

Performing an examination that may include measuring height and weight; observing the child’s movement patterns; making a hands-on assessment of muscle strength, tone, and flexibility; and testing the child’s balance

Performing specific tests to determine motor development such as skipping, walking on a straight line, or a balance beam

Possible screening of hand use, vision, language skills, intellect, and other areas of development

Referring the family and child to other health care professionals who can participate in a team effort to address the child’s needs

Physical therapists work with children with DCD to improve muscle strength, coordination, and balance, and help them develop skills to improve their daily activities and quality of life.

Improving strength. Your physical therapist will teach you and your child exercises to increase muscle strength. The therapist will identify games and fun tasks that improve strength, reduce obesity, and increase cardiac health.

Improving balance. Your therapist may use equipment such as a balance beam to improve your child’s one-foot standing, walking with one foot directly in front of the other foot, and jumping to the floor.

Improving body awareness. Your physical therapist might have your child participate in obstacle courses to help your child with learning how to plan movement.

Improving skills through task-oriented and task-specific learning. Your physical therapist may work individually with you or recommend a community program to help your child learn a specific task such as bike riding. The therapist may suggest adaptations, such as a 3-wheeled bike or training wheels, to keep your child safe while accomplishing a new skill.

At a Glance

There are a number of ways specialists can help kids with DCD.

Occupational therapy and physical therapy are key treatments for kids with DCD.

There are no medications to treat DCD.

Whether you suspect that your child has developmental coordination disorder (DCD) or you know for sure, it’s important to get treatment as early as possible. But what does that involve?

There is no medication or “cure” for DCD (sometimes known as dyspraxia). There are therapies that can help improve motor skills, however. Different types of specialists may work with kids who have DCD.

Occupational therapists focus on coordination. Physical therapists may work on muscle strength. And other professionals may treat challenges that often co-occur with DCD. Learn more about treatment for kids with DCD.

Therapies for DCD

Occupational therapy is the primary treatment for DCD. It helps kids gain motor skills and learn to do basic tasks that are needed for school and everyday living. These tasks include things like writing, typing, tying shoes and getting dressed.

An occupational therapist (OT) may work on multiple aspects of motor control. These include:

Fine motor skills

Gross motor skills

Motor planning

An OT may start by doing an evaluation to determine where a child has weaknesses. (There are other professionals who can also evaluate for movement issues.) From there, the therapist will come up with techniques and activities to address those weak spots. There are a number of ways OTs can help kids with DCD learn specific tasks and improve skills.

Your child’s school may provide occupational therapy for free through an IEP. There are also private OTs who work with kids for a fee. (Some insurance companies may cover OT for DCD.)

Kids with DCD may also get physical therapy (PT) to help improve weak muscles that are needed for motor activities. PT can help improve balance and coordination, too. That can make it easier for kids with DCD to do some basic daily living and school tasks.

Treatment for Co-Occurring Issues

DCD rarely occurs on its own, so kids with this condition may get treatment for other issues, as well. Many kids with DCD also have ADHD, for example. To treat ADHD symptoms, they may take medication or do behavior therapy. Other issues that commonly co-occur include:

Learning issues like dyslexia

Speech and language issues

Slow processing speed

Sensory processing issues

Mental health issues like anxiety

Autism

Kids with DCD have unique sets of difficulties. So it’s important that they get treatment for all of the issues and challenges they have.

Support in School for DCD

Kids with DCD might get supports at school to help keep their trouble with motor skills from impacting learning. These supports might include assistive technology, such as:

Dictation (text-to-speech) software

Touchscreens

Keyboards

Paper with wide, colored or raised lines

Kids might also get accommodations in class. These might include worksheets that have the problems already written on them. Students might also get verbal and visual demonstrations to help with directions.

Some parents wonder if kids with DCD or dyspraxia should attend gym class. Read what an expert says.

Ways to Help With DCD at Home

There are many things you can do to support your child with DCD. Try activities that can help improve fine motor skills and gross motor skills. Boost your child’s self-esteem by sharing success stories of people with motor skills issues. And if you recently found out your child has DCD, learn some steps you can take to start getting the right help.

One Comment