Hypotonia

Table of Contents

What is a Hypotonia?

Hypotonia, commonly known as floppy baby syndrome, is a state of low muscle tone (the amount of tension or resistance to stretch in a muscle), often involving reduced muscle strength.

Hypotonia is the medical term for decreased muscle tone.

Healthy muscles are never fully relaxed. They retain a certain amount of tension and stiffness (muscle tone) that can be felt as resistance to movement.

For example, a person relies on the tone in their back and neck muscles to maintain their position when standing or sitting up.

Muscle tone decreases during sleep, so if you fall asleep sitting up, you may wake up with your head flopped forward.

Hypotonia isn’t the same as muscle weakness, although it can be difficult to use the affected muscles.

In some conditions, muscle weakness sometimes develops in association with hypotonia.

It’s most commonly detected in babies soon after birth or at a very young age, although it can also develop later in life.

An infant with hypotonia exhibits a floppy quality or “rag doll” feeling when he or she is held.

•Infants may lag behind in acquiring certain fine and gross motor

developmental milestones that enable a baby to hold his or her head up

when placed on the stomach, balance themselves or get into a sitting

position and remain seated without falling over.

• There is a tendency for hip, jaw, and neck dislocations to occur.

• Some children with hypotonia may have trouble feeding if they are unable to suck or chew for long periods.

• A child with hypotonia may also have problems with speech or exhibit shallow breathing.

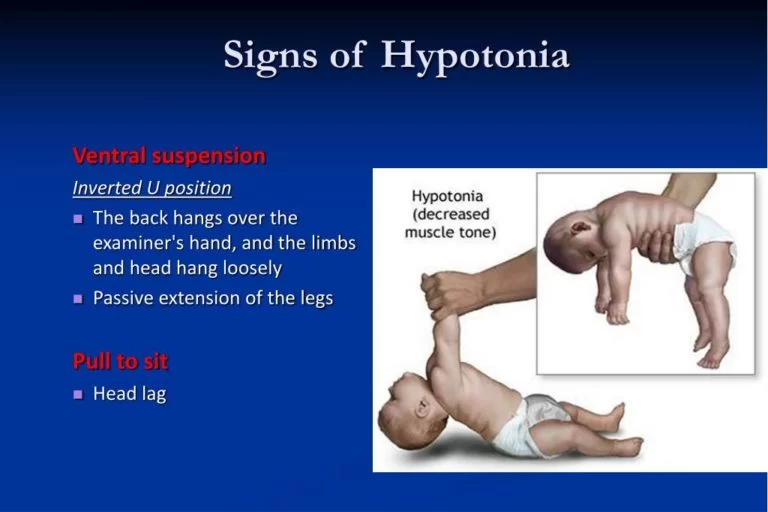

Signs and Symptoms of Hypotonia

Difficulty maintaining head control

Difficulty sitting upright without significant lean or support

Slow to attain motor milestones

Difficulty transitioning in and out of positions

Clumsy or inefficient movement patterns

Global Developmental delay

Difficulty with hand-eye coordination

Prefer to observe rather than participate

Low frustration tolerance with physically challenging tasks

Hypotonia present at birth is often noticeable by the time a child is 6 months old, if not before.

Newborn babies and young children with severe hypotonia are often described as being “floppy”.

having little or no control of their neck muscles, so their head tends to flop

feeling limp when held, as though they could easily slip through your hands

being unable to place any weight on their leg or shoulder muscles

their arms and legs hang straight down from their sides, rather than bending at their elbows, hips, and knees

finding sucking and swallowing difficult

a weak cry or quiet voice in infants and young children

A child with hypotonia often takes longer to reach motor developmental milestones, such as sitting up, crawling, walking, talking, and feeding themselves.

An adult with hypotonia may have the following problems:

clumsiness and falling frequently

difficulty getting up from a lying or sitting position

an unusually high degree of flexibility in the hips, elbows, and knees

difficulty reaching for or lifting objects (in cases where there’s also muscle weakness)

Floppy baby syndrome

The term “floppy infant syndrome” is used to describe abnormal limpness when an infant is born. Infants who suffer from hypotonia are often described as feeling and appearing as though they are “rag dolls”. They are unable to maintain flexed ligaments and are able to extend them beyond normal lengths. Often, the movement of the head is uncontrollable, not in the sense of spasmatic movement, but chronic ataxia. Hypotonic infants often have difficulty feeding, as their mouth muscles cannot maintain a proper suck-swallow pattern or a good breastfeeding latch.

Developmental delay

Children with normal muscle tone are expected to achieve certain physical abilities within an average time frame after birth. Most low-tone infants have delayed developmental milestones, but the length of delay can vary widely. Motor skills are particularly susceptible to the low-tone disability. They can be divided into two areas, gross motor skills, and fine motor skills, both of which are affected. Hypotonic infants are late in lifting their heads while lying on their stomachs, rolling over, lifting themselves into a sitting position, remaining seated without falling over, balancing, crawling, and sometimes walking. Fine motor skills delays occur in grasping a toy or finger, transferring a small object from hand to hand, pointing out objects, following movement with the eyes, and self-feeding.

Speech difficulties can result from hypotonia. Low-tone children learn to speak later than their peers, even if they appear to understand a large vocabulary, or can obey simple commands. Difficulties with muscles in the mouth and jaw can inhibit proper pronunciation, and discourage experimentation with word combination and sentence-forming. Since the hypotonic condition is actually an objective manifestation of some underlying disorder, it can be difficult to determine whether speech delays are a result of poor muscle tone, or some other neurological condition, such as intellectual disability, that may be associated with the cause of hypotonia. Additionally, lower muscle tone can be caused by Mikhail-Mikhail syndrome, which is characterized by muscular atrophy and cerebellar ataxia which is due to abnormalities in the ATXN1 gene.

Muscle tone vs. muscle strength

The low muscle tone associated with hypotonia must not be confused with low muscle strength or the definition commonly used in bodybuilding. Neurologic muscle tone is a manifestation of periodic action potentials from motor neurons. As it is an intrinsic property of the nervous system, it cannot be changed through voluntary control, exercise, or diet.

“True muscle tone is the inherent ability of the muscle to respond to a stretch. For example, quickly straightening the flexed elbow of an unsuspecting child with normal tone, will cause their biceps to contract in response (automatic protection against possible injury). When the perceived danger has passed, (which the brain figures out once the stimulus is removed), the muscle relaxes and returns to its normal resting state.”

“…The child with low tone has muscles that are slow to initiate a muscle contraction, contract very slowly in response to a stimulus, and cannot maintain a contraction for as long as his ‘normal’ peers. Because these low-toned muscles do not fully contract before they again relax (muscle accommodates to the stimulus and so shuts down again), they remain loose and very stretchy, never realizing their full potential of maintaining a muscle contraction over time. “

Causes of Hypotonia

Hypotonia is a symptom rather than a condition. It can be caused by a number of different underlying health problems, many of which are inherited.

Hypotonia can also sometimes occur in those with cerebral palsy, where a number of neurological (brain-related) problems affect a child’s movement and co-ordination, and after serious infections, such as meningitis.

In some cases, babies born prematurely (before the 37th week of pregnancy) have hypotonia because their muscle tone isn’t fully developed by the time they’re born.

But provided there are no other underlying problems, this should gradually improve as the baby develops and gets older.

Read more about the causes of hypotonia.

Some conditions known to cause hypotonia include:

Congenital – i.e. disease a person is born with (including genetic disorders presenting within 6 months)

–Genetic disorders are the most common cause

22q13 deletion syndrome a.k.a. Phelan–McDermid syndrome

3-Methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency

Achondroplasia

Aicardi syndrome

Autism spectrum disorders

Canavan disease

Centronuclear myopathy (including myotubular myopathy)

Central core disease

CHARGE syndrome

Cohen syndrome

Costello syndrome

Dejerine–Sottas disease (HMSN Type III)

Down syndrome a.k.a. trisomy 21 — most common

Ehlers–Danlos syndrome

Familial dysautonomia (Riley–Day syndrome)

FG syndrome

Fragile X syndrome

Griscelli syndrome Type 1 (Elejalde syndrome)

Disorder Growth Hormone Disorder Pituitary Dwarfism

Holocarboxylase synthetase deficiency / Multiple carboxylase deficiency[6]

Krabbe disease

Leigh’s disease

Lesch–Nyhan syndrome

Marfan’s syndrome

Menkes syndrome

Methylmalonic acidemia

Myotonic dystrophy

Niemann–Pick disease

Nonketotic hyperglycinemia (NKH) or Glycine encephalopathy (GCE)

Noonan syndrome

Neurofibromatosis

Patau syndrome a.k.a. trisomy 13

Prader–Willi syndrome

Rett syndrome

Septo-optic dysplasia (de Morsier syndrome)

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA)

Succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency (SSADH)

Tay–Sachs disease

Werdnig–Hoffmann syndrome – Spinal muscular atrophy with congenital degeneration of anterior horns of the spinal cord. Autosomal recessive

Wiedemann–Steiner syndrome

Williams syndrome

Zellweger syndrome a.k.a. cerebrohepatorenal syndrome

-Developmental disability

Cerebellar ataxia (congenital)

Sensory processing disorder

Developmental coordination disorder

Hypothyroidism (congenital)

Hypotonic cerebral palsy

Teratogenesis from in-utero exposure to Benzodiazepines

Acquired

Acquired – i.e. onset occurs after birth

-Genetic

Muscular dystrophy (including Myotonic dystrophy) – most common

Metachromatic leukodystrophy

Rett syndrome

Spinal muscular atrophy

-Infections

Encephalitis

Guillain–Barré syndrome

Infant botulism

Meningitis

Poliomyelitis

Sepsis

–Toxins

Infantile acrodynia (childhood mercury poisoning)

–Autoimmunity disorders

Myasthenia gravis – most common

Abnormal vaccine reaction

Celiac disease

-Metabolic disorder

Hypervitaminosis

Kernicterus

Rickets

-Neurological

Traumatic brain injury, such as the damage that is caused by Shaken baby syndrome

Lower motor neuron lesions

Upper motor neuron lesions

–Miscellaneous

Central nervous system dysfunction, including Cerebellar lesions and cerebral palsy

Hypothyroidism

Sandifer syndrome

Neonatal Benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome in children born to mothers treated in late pregnancy with benzodiazepine medications

Differential Diagnosis

It is important to rule out any potential underlying etiology that may be presenting as Hypotonia. Some of these conditions may require more immediate medical intervention.

Detailed Patient and Family History: Details of the pregnancy, delivery and postnatal period are extremely helpful. Any family history of conditions that present like hypotonia are also important.

Developmental Assessment: To understand the acquisition of motor milestones and the implications on the child’s physical, social, and emotional development.

Physical Exam: Includes muscle tone, neurologic reflexes, muscle strength, postural control, joint laxity, protective responses, and equilibrium/righting reactions.

Muscle Strength vs Muscle Tone

The muscles in our bodies each have a resting muscle tone. Muscle Tone is defined as a muscle’s potential ability to respond or counter an outside force, a stretch, or a change in direction. Proper muscle tone enables a child to respond quickly to an outside force, either through balance responses, righting reactions, or protective reactions. It also allows a child’s muscles to quickly relax once the perceived change is gone. A child with hypotonia has muscles that are slow to initiate a contraction against an outside force and are unable to sustain a prolonged muscle contraction.

Muscle Strength refers to the muscle’s ability to actively contract and create a force to respond to resistance (pulling, pushing, lifting, etc). Although strength and tone are different, when a muscle is not in an ideal position to be ready for a contraction, the muscle strength will be impaired.

Hypotonia Can Manifest As Deficits in:

Sensory Processing, in which the vestibular, proprioceptive, and/or tactile systems fail to alert the brain of changes in body position.

Praxis or Motor Planning, in which the body is unable to formulate the proper motor response.

Balance, with the body unable to sustain co-activation of muscle groups working against gravity both statically and dynamically.

Coordination, with difficulty coordinating upper and lower body movements or visual systems to produce fluid and efficient movements.

Hypotonia Through the Years

Newborns and infants may display poor head control. Babies may seem to “slip out of your hands”, and have trouble keeping body erect when you carry them. When lying on their backs, babies with hypotonia will often rest with arms and legs extended outward, and sometimes resist bearing weight when placed on stomachs, held in supported sitting or supported standing.

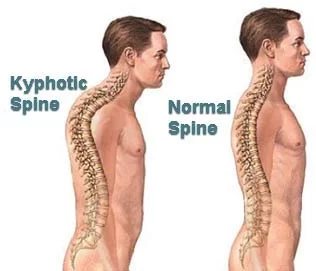

Young children with hypotonia may tend to lean excessively forward when they are sitting up, failing to activate the trunk musculature to keep them erect. They may favor the “W-sit” position to lock into sitting, without engaging their core and postural muscles. Children with low muscle tone may display delays in achieving gross motor milestones and have difficulty learning to roll, sit, crawl, and walk independently.

Older children with hypotonia may favor passive vs. active participation in school and extracurricular activities, displaying low frustration tolerance during physically challenging tasks. They may get tired easily and with fatigue, movements become more labored and clumsy. Children with hypotonia may struggle in the classroom setting, despite their cognitive abilities. Sitting for prolonged time at a desk or during tabletop activities may prove challenging and children may lose focus simply because of physical stress. As children get older, hypotonia may impact gait and running patterns. Children may turn out feet and present with little to no arch support.

How to Diagnose hypotonia?

If your child is identified as having hypotonia, they should be referred to a specialist healthcare professional, who will try to identify the cause.

The specialist will ask about your family history, pregnancy, and delivery, and whether any problems have occurred since birth.

A number of tests may also be recommended, including blood tests, a CT scan, or an MRI scan.

Physiotherapy Treatment of Hypotonia

Depending on the cause, hypotonia can improve, stay the same, or get worse over time.

Babies with hypotonia that results from being born prematurely will usually improve as they get older.

Babies with hypotonia caused by an infection or another condition will usually improve if the underlying condition is treated successfully.

Unfortunately, it’s often not possible to cure the underlying cause of hypotonia.

Hypotonia that’s been inherited will persist throughout a person’s life, although the child’s motor development may steadily improve over time in cases that are non-progressive (don’t get worse).

Treatment can also help improve functions such as mobility and speech. In these cases, treatment may involve physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and speech and language therapy.

Goals of Treatment

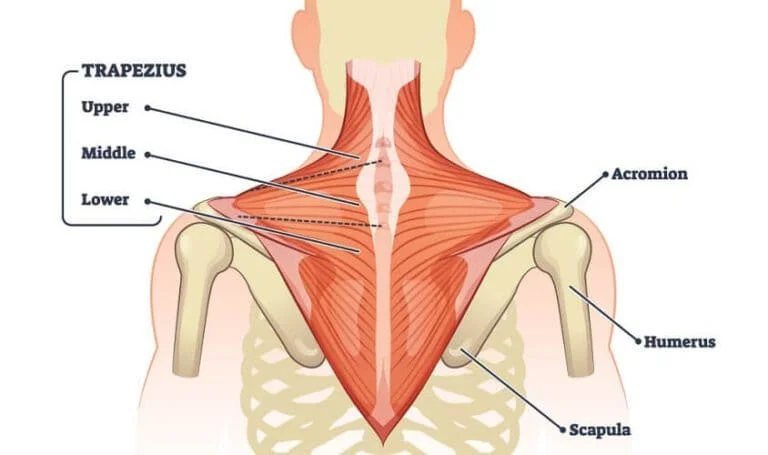

Address Proximal Strength and Support in order to Facilitate Distal Strength and Function

Improve Postural Control

Facilitate Motor Development and Foundations of Motor Planning

Improve Postural Responses and Protective Reactions

Address Fluidity and Efficiency of Movements

Improve Functional Strength

Treatment Strategies

- Be Patient: Because children with hypotonia often do not demonstrate motor response immediately, both therapists and caregivers have a tendency to give up on what they are doing and move on to another activity. Patience is important, as with adequate time and proper prompting the child will be able to achieve objectives in some capacity. Waiting for this response is key. By sustaining the same activity and modifying that activity to ensure success, you can facilitate muscle activation and fluidity of movement patterns.

- Follow Developmental Sequence: Children with hypotonia often struggle with the acquisition of motor milestones. Allow the child to experience each developmental stage sequence regardless of the age therapy is initiated. Encourage transitions between each important body position: supine, prone, seated, tall kneel, half kneel, and standing.

- Promote Proper Alignment: Build strength over the properly aligned symmetrical base of support in all developmental stages. If you are working in a sitting, before beginning the activity ensure the pelvis is in a neutral position. If you are working in standing ensure feet are properly aligned and weight-bearing through support surface in order to promote functional muscle development and eliminate potential compensations.

- Grade Input: Try not to startle the child with sudden movements, do not push or pull, and allow the child to activate on his or her own to maximize work and minimize collapse.

- Decrease Support Over Time: Start with a higher or more proximal base of support while handling and slowly lower as the child gains control. When addressing postural control, begin with upper back/shoulder girdle support and slowly lower as the child begins to activate and strengthen, allowing the child to achieve more functional independence.

- Make Tasks Functional: Focus on function. Talk with family and caregivers about day-to-day needs. Whether it is assisting with activities of daily living (ADLs) such as dressing or getting in and out of the chair at school, help with motor planning in both a practical and helpful manner.

- Set Up for Success: Break down tasks into manageable components. Allow the child the necessary time and energy to achieve each task. And do not forget about positive encouragement!

Activity Ideas

- Use the Therapy Ball to:

Increase demands on the child and inhibit passive collapsing into gravity

Facilitate motor control

Promote muscle strength

Facilitate transitions

Provide vestibular input

Practice righting reactions and protective responses.

2. Use Developmental Positions

In Prone: Use movement to enable the child to weight shift and disperse weight bearing symmetrically through the upper extremities.

In Quadruped: Direct graded force through the pelvis to elongate the spine and to elicit symmetric weight bearing through upper and lower extremities (can use a foam roller to facilitate).

In Tall Kneel: Utilize support at pelvis to help child weight shift over lower center of gravity, encourage trunk activation, and aid in transition from tall kneel through half kneel to stand without use of upper extremities.

The Cube Chair is a great surface to practice tall kneeling position.

3.Use Joint Compressions

Joint Compressions, when done appropriately by trained clinicians, can help to promote increased co-activation of muscles around the joint and help child maintain joint in alignment against gravity.

Perform compressions on well-aligned joints supported by the therapist (begin proximal to distal).

Use graded force to approximate the joints without overloading them, and joint distraction that is graded to align the joints without overstressing them.

4. Use Tactile Cues

By facilitating appropriate muscles during therapeutic intervention, we can help child build awareness and promote initiation of force production.

Tactile input can promote co-activiation of muscles which support joint.

Light pressure massage also helps promote muscle activation, increase bone growth and mineralization in children with hypotonia.

5. Encourage Active Play

Bilateral Play (promoting utilizing both sides of the body and movements which cross the midline)

Music is a great motivator, these egg shakers are a big hit at our house

Sports Skills (activities that incorporate hand-eye coordination, reaching, squatting, balance)

For some creative ideas visit our Activity of the Week #1 and Activity of the Week #2!

Navigating Obstacles

Play tunnels are always a fun way to build strength, motor planning, and endurance!

Climbing up and Down (targeting concentric and eccentric muscle activation)

This is a great soft step to practice climbing!

Supported Standing, Cruising, and Walking

The Cube chair is also a great surface to practice supported standing!

For more toy ideas that promote standing visit our post here!

4 Comments