Pes Planus

Table of Contents

Introduction

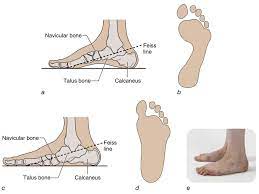

Pes planus/ pes planovalgus (or flat foot) is a foot deformity in which loss of the medial longitudinal arch of the foot, heel valgus deformity, and medial talar prominence are seen. This is frequently observed with the medial arch of the foot coming near (then typically expected) to the ground or making contact with the ground.

All typically developing infants are born with flexible flat feet, with arch development first seen around 3 years of age and then frequently only attaining adult values in arch height between 7 and 10 years of age.

Classification

The classification of the pes planus is depend on two aspects:

Arch height:

- The best parameter to distinguish medial longitudinal arch structure was found to be a ratio of navicular height to foot length.

- It is received that the flatness of normal children’s feet and their age are inversely proportioned.

Heel eversion angle:

- Heel eversion or hindfoot valgus is usually accepted as a normal finding in young, newly walking children and is expected to decrease with age.

- The eversion of the heel has been continuously used for determining the posture of the child’s foot.

Resting the calcaneal stance position is a more recent method. It has guided physicians in the assessment of the baby’s foot posture and calcaneal eversion has been recommended to decrease by a degree every 12 months to a vertical position by age 7 years. A vertical heel is optimal for foot function. The average rear foot angle for children from 6 to 16 years is 4° (ranging from 0 to 9° valgus). Whether the flat foot construction is rigid or flexible.

Flexible flat foot (flexible FF):

- The longitudinal arches of the foot are existing on heel elevation (tiptoe standing) and are non-bearing but disappear with full weight bearing on the foot.

- FF is termed developmental FF when observed in small babies and toddlers and is part of basic development.

- Between the ages of eight and ten, however, a physician can consider this a true FF.

Rigid flat foot:

- The longitudinal arches of the foot are not present in both heel elevation (tiptoe standing) and weight bearing.

- This is usually connected with underlying pathology.

Epidemiology

- Roughly 20% to 37% of an individual has some degree of pes planus, With most cases being the flexible variety.

- It is more usual in babies (about 20-30% of children with some form of flat feet) with most babies going on to develop a normal arch

- by ten years old.

- Genetics plays a vital role with it typically running in families.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

Medial arch of the foot

- The calcaneus, navicular, talus, first 3 cuneiforms, and the first 3 metatarsals make up the medial longitudinal arch.

- This arch is hold up by posterior tibial tendon, plantar calcanea navicular ligament, deltoid ligament, plantar aponeurosis, and flexor hallucis longus and brevis muscles.

- injury or Dysfunction to any of these body parts can cause acquired pes planus.

Pathophysiology

- The pathophysiology of pes planus may vary greatly based on whether it is congenital or acquired, and then whether it is flexible or fixed.

- In considering developmental flatfoot, the medial longitudinal arch of the foot usually develops by the age of five or six.

- This happens as the fat pad in babies is slowly absorbed, balance increases, and skilled movements are acquired.

- In some children, although, the arch fails to develop which can be an outcome of tightness in the calf muscles, laxity in the Achilles tendon, or poor core stability in other areas like around the hips.

Dynamic factors

Soft tissue factors

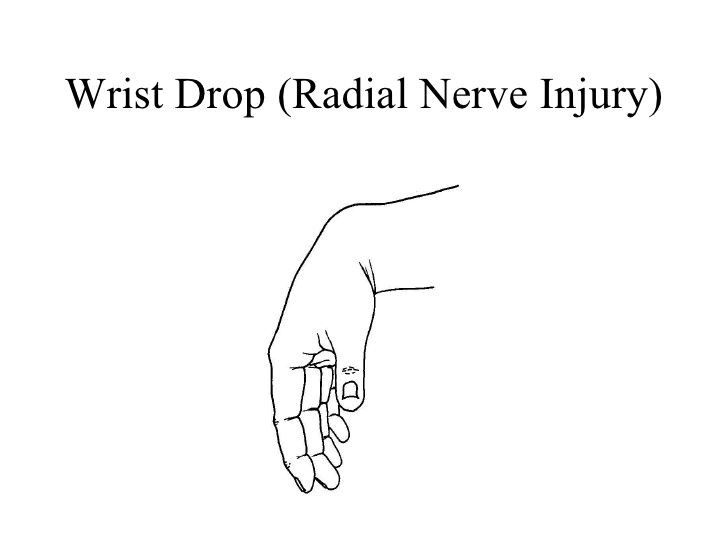

- Insufficiency of the posterior tibial tendon: When this happens, forefoot valgus takes place.

- Over the long term, this creates Achilles tendon contractures and transforms the gastrocnemius and soleus muscle complex into heel events (rather than inverters).

- When a peroneal spastic flatfoot is observed, the peroneal tendon which crosses over the subtalar joint frequently goes into spasm.

- This is secondary to subtalar inflammation.

Other muscular dysfunctions can occur:

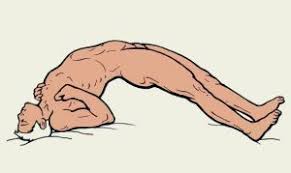

- After an injury or enforced recumbency, the muscles may be weak for that moment and the arch consequently falls when walking is resumed.

- A more lasting form of muscle weakness accompanies a usually poor posture.

- The child (frequently a pre-adolescent girl) presents a familiar flabby contour with head stuck forward, mouth open, chest flat, back rounded, and abdomen protuberant.

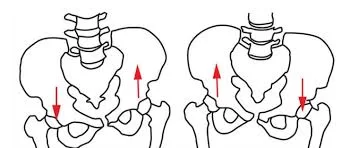

- The gluteal muscles are disturbed largely by posture (Wiles 1949).

- They try to help to straighten the hip and knee, and to twist the limb outwards.

- This twist may not be imparted to the foot which is anchored to the ground, and so the rest of the limb turns outside relative to the foot.

- As a result, the arch is lifted and the line of weight is corrected only when the glutei work properly.

Neurological factors

- In usual development, a child has to learn to balance first its head, then its trunk, and eventually to balance the entire body on the feet.

- The difficult art is not required in the time of early months of life, but sometimes the balancing reflexes fail to grow even after the baby has begun to walk.

- In that event, the arch inevitably collapses with the entire body weight.

- Myelination of the pyramidal fibers to the foot is incomplete at birth and the plantar responses in babies is an extensor.

- If the infantile flat foot persists into early childhood, the extensor responses can be preserved too, and it is tempting to presume that balancing may not be easily learned until myelination is complete.

Static factors

- Boney architecture of the medial longitudinal arch. Here modifying the morphology of the joints of the midfoot would affect stability.

- Fixed or rigid pes planus is because of a structural abnormality.

- As seen in etiology, this most frequently presents as a tarsal coalition.

- The restricted range is viewed in the subtalar and midfoot motion when there is a failure of the tarsal bones to separate.

- This coalition may be cartilaginous, fibrous, or even boney.

- This condition frequently causes pain and inflammation of the joints.

- Other conditions connected with rigid pes planus incorporating accessory navicular bone, congenital vertical talus, or other congenital hindfoot pathology.

- The spring ligament complex has been seen as the crucial stabilizer, but clarity still lacks in the literature.

- Plantar fascia gives stability to the medial longitudinal arch via the windlass effect.

- In conditions where the laxity of these tissues is affected, for example in EDH, arch stability may be compromised.

Causes of Pes Planus

The causes of pes planus have too many factors implicated and may be either congenital or acquired.

Congenital Pes Planus

- Congenital pes planus is classified as developing in the 1st years of life.

- Both flexible FF and rigid FF may present.

- At birth and within early childhood pes planus is a typical observation of the development and is termed flexible flat foot (FF).

- It is ascribed to osseous and ligamentous laxity, immature neuromuscular control, and the presence of adipose tissue under the

- medial longitudinal arch (MLA), building the arch to appear flat. In fact, in the time of early years of gait in toddler years, a child will use their whole foot on the ground for balance.

- A shift of their weight-bearing axis to the first or second metatarsal joint induces a flatfoot posture.

When flexible FF is viewed in older children (typically those above eight years of age) and adults, the following must be considered:

- General/ global hypermobility, involving conditions like Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDH) and Down Syndrome.

- Conditions with improved tone, for example, cerebral palsy.

Higher body mass index (BMI).

- A note: While increased BMI and even obesity have been ascribed to an improved predisposition to flexible FF, more recent

- investigations call these findings into question. These studies, which have taken into account a more comprehensive foot

- morphology (not simply footprint measurements) have not found greater rates of flexible FF in pediatric populations. These

- have, however, been done with participants with higher BMI and not an important diagnosis of obesity.

Subtalar joint morphology

- Recent research has suggested the variance in subtalar joints.

- One such study highlighted two various types:

- The first is a firmer supporting joint and the second weaker joint where the anterior articulation in the subtalar joint is absent.

- The absent articulation permits the FF posture to develop.

- An example of rigid FF is a tarsal coalition, where there is a failure of the tarsal bones to separate.

- This causes a bony, often cartilaginous, or even fibrous bridge between two or more of the tarsal bones.

Other examples of congenital pes planus involve

- Congenital vertical talus

- Congenital talipes equinovarus

- Tibial torsional deformity

- Presence of the accessory navicular bone.

- General ligament laxity

- Genetic malformations such as Down syndrome and Marfan syndrome

- Familial factors

- Peroneal spasm

- Vertical talus

Acquired Pes Planus

Acquired pes planus may come from:

- Diabetes Foot and ankle injuries such as rupture or dysfunction of the posterior tibial tendon.

- Some medical conditions like arthritis, spina bifida, cerebral palsy, Arthrogyroposis, and muscular dystrophy.

- Flat feet can also happen as an outcome of pregnancy.

- Iatrogenic factors like posterior tibialis tendon (PTT) transfer.

- Traumatic injury

Signs and symptoms of Pes Planus

History

- In adults: Often “rolling of the ankle”/ ankle sprains

- Babies presenting with pes planus are usually asymptomatic, usually only becoming symptomatic during adolescence.

- Pain is frequently felt by indicated at the medial longitudinal arch and ankle.

- In children and adolescents, pain secondary to flatfeet can be described as pain in the arch of the feet or cramps at night.

- In adults there can be complaints of pain because of strained muscles and connecting tissues in the midfoot, heel, lower leg, knee, hip, and or back. In more advanced changes patients can complain of an altered gait pattern.

Observation

- The foot can come up as flat or ‘rocker-bottom’.

- In standing- Calcaneal valgus is apparent, the medial arch will be dropped and there will be foot eversion.

- Gait.

- Test stance on medial and lateral borders of feet to assess the mobility of foot joints.

- Walking on heels.

- Being able to walk on heels demonstrates the flexibility of the Achilles tendon.

- Viewed from the back side (posteriorly), looking for the “too many toes sign”

- Look at running or walking shoes

- Uneven distribution of body weight with resultant one-sided wear of shoes leading to further injuries.

With palpation

- A contracted Achilles tendon can show as a limitation in dorsiflexion.

- Test subtalar and transverse tarsal motion.

- Flexible pes planus will permit mobility in these joints.

- Subtalar motion: Examiner stabilizes ankle with one hand, calcaneus in the other.

- The calcaneus is then inverted and everted. Normal ROM is between 20° and 60°, with Inversion being two percent more than the ROM of eversion.

- Tarsal motion: Grab the calcaneus in one hand and forefoot in the other.

- The normal adduction of the forefoot is about 30°, and abduction is about 15°.

- If ranges are reduced consider a coalition.

- Ask some question to the patient about the onset of deformity, timing of symptoms, severity of old and current symptoms, history of trauma, family history, surgical history, and past medical history (involving hypertension, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, sensory neuropathies, seronegative spondyloarthropathies, and obesity.

Associated Co-morbidities

- Co-morbidities involve but are not limited to neurological conditions like cerebral palsy; genetics for example Down syndrome, Marfan syndrome, or Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome; charcot joint; tibialis posterior dysfunction; Obesity; arthropathies; Shprintzen-Goldberg syndrome.

Diagnostic Procedure

Footprints

- It is still contended if footprints consider the real morphology of the medial longitudinal arch. Recent development found a direct correlation between dynamic pressure patterns and static footprints.

X-rays

- X-rays categorize the feet as having normal, slightly flat, and moderate arches.

- In FF this is not routine.

Foot-posture index (FPI-6)

Supination resistance test

- This test is utilized to estimate the magnitude of pronation moments.

- The foot is manually supinated.

- The greater the force required, the higher the supination resistance and the stronger the predatory forces.

- This test is subjective.

Jack’s test and Feiss angle (are related)

- Performing Jack’s test.

- The hallux is manually dorsiflexed while the baby is standing. If the medial longitudinal arch rises because of dorsiflexion of the hallux, the foot is reflected as a flexible flat foot.

- If the medial longitudinal arch remains not changed, the test resulted in a rigid flat foot.

- The goal of this test is to check the foot flexibility and the onset of the windlass mechanism by tensioning the plantar fascia through the extension of the first metatarsophalangeal joint.

- The Feiss line is the line interconnecting the malleolus medialis, navicular, and 1st metatarsal head.

- The predisposition of this line with the ground improves when the first metatarsophalangeal joint is dorsiflexed (Jack’s test).

- This dorsiflexion activates front foot supination and raises the arch height (140°± 6°).

Tip-toe

- To differentiate fixed and flexible pes planus.

Ankle range

- Babies’ ankle range assessment is usually an unreliable measure, as typically checked when the child is non-weight-bearing.

- So it is recommended that therapists look at a baby’s ability to squat, heel walk, and improve stride length.

Medical Management

Flexible Pes planus

- The merit of treatment for all flexible FF remains inconclusive, with proof showing that foot orthoses create improvements in children with pes planus.

- It remains laborious to conclude if spontaneous physiological arch improvement took place or if the effect of intervention caused the arch improvement.

- There is little evidence for the treatment of asymptomatic, flexible, pediatric flat feet in a child who has no underlying medical issues.

- Treatment of symptomatic, flexible flat feet is usually accepted for babies with contributory background factors or secondary complications, or if pes planus persists past childhood.

- Evidence supports the utilization of non-surgical interventions for painful pes planus.

- The baby should be fitted with a flat, lace-up shoe with a firm heel and MLA support, a broad and deep toe box, and the ‘toe break’ at the junction in the middle of the anterior third and posterior two-thirds of the shoe.

- In babies 10 years and older, FF is considered permanent, therefore long-term orthotics may be used to prevent secondary problems, specifically in overweight or athletically active children.

- Treatment is dependent on etiology and NSAIDS are best for pain.

Rigid Pes planus

- Surgery is mandatory in rigid pes planus and in cases resistant to therapy to decrease symptoms.

- Most surgical methods goal at realigning foot shape and mechanics.

- These surgeries might be tendon transfers, realignment osteotomies, or arthrodesis, and where other surgeries fail, triple arthrodesis is performed.

Congenital pes valgus

For this treatment, researchers have defined the best possible treatments depending on the age of the person/child.

In a child smaller than 2 years

- An extensive release with lengthening of the Achilles tendon and fixation procedure is suggested.

- It is minimally invasive than other techniques, due to there being no tendon transfer or bony procedures required.

- The explanation might be because of the greater adaptability of the cartilaginous structures.

In a child with a neural tube defect, younger than 2 years of age

- An extensive release with a tendon transfer procedure is suggested.

- A neuromuscular imbalance between a weak Tibialis Posterior tendon and a strong evertor of the foot might be responsible for this condition.

- The best outcome is found for this operation which goals to correct this imbalance.

In a child more than two years of age

- An extensive release with a tendon transfer procedure is proposed.

- The surgical correction becomes improving difficult in older children due to secondary changes in the bone.

- This procedure outcome is the best for babies whose walking and standing potential has been established.

- In case of failure of precedent procedures, a bony procedure can be considered.

- There are best results for babes of four years and older with these procedures.

- Every surgery is generally followed by a plaster cast for two to three months.

- The recovery after surgery takes about six months to one year to heal totally and to recover completely on a functional level.

Physiotherapy treatment

How can Physiotherapy help?

- Minimize pain

- Increase foot flexibility

- Strengthen weak muscles

- Train proprioception

- Patient education and reassurance.

- As part of the assessment process, the physiotherapist may assist in evaluating the gait, gross motor skills, and the impact the foot deformity has on functional activities.

- Also assess the endurance, speed, fatigability, pain, and ability to walk on different terrains, with a focus on assessing function, not just structural abnormalities.

Modalities

- Heat and cold therapy are given to enhance relaxation and decrease pain.

- It is necessary to use ice after exercise and after any activity that causes discomfort.

- Ultrasound and pulsed electrical stimulation may also be used to decrease the pain.

- Electric stimulation will help to increase blood circulation, thus enhancing the healing process and diminishing any swelling or discomfort.

Exercise

- Exercise will ease foot discomfort and restore function.

- It is normal to experience some discomfort, aching, or stretching when performing exercises.

Heel stretch

- Start with standing with the hands resting on a wall, chair, or railing at the shoulder or eye level.

- Keep up one leg forward and the other leg extended behind you.

- Press both heels gently into the floor.

- Keeping the spine straight, bend the front leg and push yourself into the wall or support, experiencing a stretch in the back leg and Achilles tendon.

- Hold this position for 20 seconds.

Tennis/golf ball rolls

- Start with sitting on a chair with tennis or golf under the right foot.

- Maintain a straight spine as you roll the ball under the foot, focusing on the arch.

- Perform this for 5 minutes.

- Then perform the other foot.

Arch lifts

- Start with standing with the feet directly underneath the hips.

- Making sure to keep up the toes in contact with the floor the entire time, and roll the weight to the outer edges of the feet as you lift the arches up as far as a person can.

- Then release the feet back down.

- The person works the muscles that help to lift and supinate the arches.

- Do 3 sets of 15 repetitions.

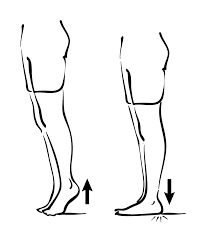

Calf raises

- Start with standing, lift the heels as high as a person can.

- A person may use a chair or wall to help support the balance.

- Hold the upper position for 10 seconds, and then lower back down to the floor.

- Do 3 sets of 15 repetitions.

- Then hold the upper position and pulse up and down for 20 seconds.

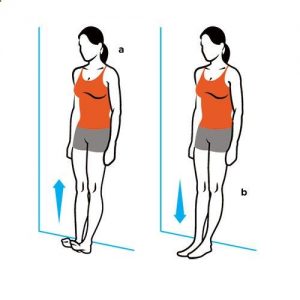

Stair arch raises

- Start with standing on steps with the left foot one step higher than the right foot.

- Use the left foot for balance as a person lower his right foot down so the heel hangs lower than the step.

- Gently lift one heel as high as a person can, focusing on strengthening the arch.

- Rotate the arch inward as the knee and calf rotate gently to the side, causing the arch to become higher.

- Gently lower back down to the initial position.

- Do 3 sets of 15 repetitions on both sides.

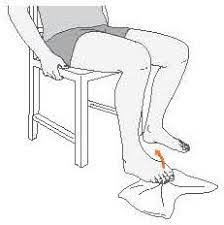

Towel curls

- Start with sitting in a chair with a towel under the feet.

- Root the heels into the floor as a person curl their toes to scrunch up the towel.

- Press the toes into the foot.

- Hold for some time and release.

- Make sure to keep up the ball of the foot pressed into the floor or towel.

- Maintain an awareness of the arch of the foot being strengthened.

- Do 3 sets of 15 repetitions.

Toe raises

For variation a person may try performing this exercise in standing yoga poses like Tree Pose, Standing Forward Bend, or Standing Split.

- While standing, press one big toe into the floor and lift up the other four toes.

- Then press the four toes into the floor and lift up the big toe.

- Do each way 10 times, holding each lift for 10 seconds.

- Then perform the exercise on the opposite foot.

- Do each side 5 times.

Manual Hammer Toe Stretching

- The patient may also use a towel to stretch the toes.

- Start with sitting on the ground with the legs perfectly outstretched and a towel muffled adequately around the toes.

- Be sure that the patient holds the towel ends with their hands and pulls the toes towards them.

- Keep themselves in this position for 30 seconds.

- The patient can also forget the towel if they like and try pulling their toes by using their hands.

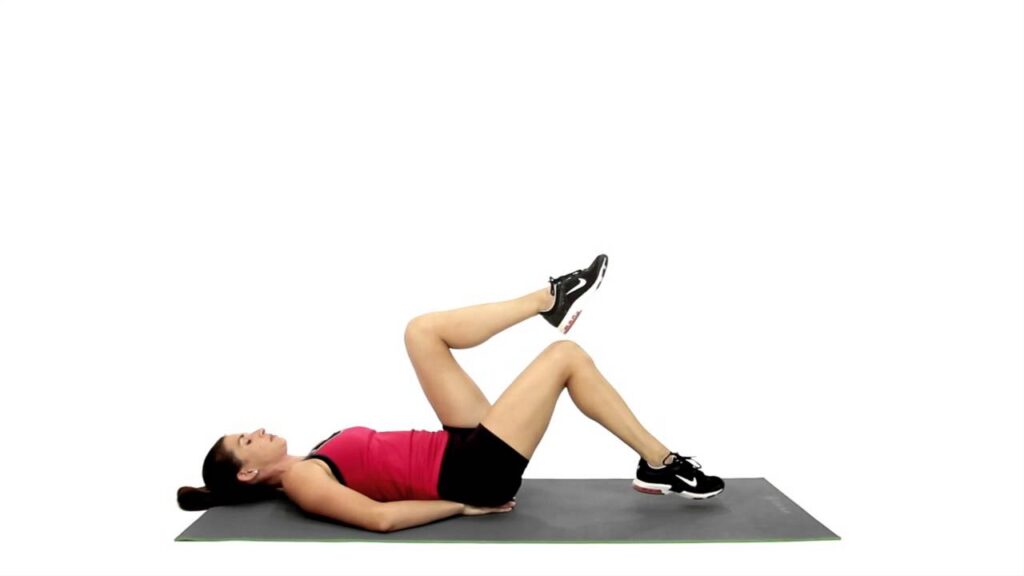

Toe Taps

- This hammer toe exercise helps a person to stretch their joint.

- As the patient lay down, gently extend the big toe towards the floor as the patient tries to point the other toes up.

- Now hold onto that position for about a second and then tap them slowly back down to the floor.

- Repeat this exercise about 10 times and then reverse this process by gently pulling the big toe up as the patient keep the other toes on the floor.

Hammer Toe Finger Splint

The Hammer Toe Finger Splint is also suggested as a “squeeze” and involves using the fingers for creating little splits between the toes for stretching them.

- Start with sitting in a comfortable position and then put one foot up and then place it right on the opposite thigh.

- After that slide the fingers slowly in between the toes, gently pinching the fingers for squeezing the toes together.

- Repeat the exercise 10 times. If the person like they may perform each toe simultaneously by putting one finger between them and pinching.

For proprioception

Proprioception exercises may be done on foam, rocker board, or Bosu ball.

- Toe and heel walking,

- Single-leg weight-bearing,

- Toe clawing of towel and pebbles,

- Forefoot standing on a stair,

- Also, the extension and toe fanning/spreading,

Specialized techniques and manual therapies like:

- Kinesio taping,

- Ankle joint mobilization and manipulation,

- Static or dynamic Cupping therapy.

- Lifestyle modification;

Preventing flat foot

Flat feet cannot always be prevented, but staying healthy and choosing good quality supportive shoes can help avoid some problems developing.

Footwear modification:

- wear footwear that has proper arch support as well as extra cushion and additional side foot support.

- orthotics and braces.

- Also, weight loss through exercise and dieting.

FAQ

This arch is supported by posterior tibial tendon, plantar calcanea navicular ligament, deltoid ligament, plantar aponeurosis, and flexor hallucis longus and brevis muscles. Dysfunction or injury to any of these structures can be the cause of acquired pes planus.

The situation is referred to as pes planus or fallen arches. It is normal in infants and generally disappears between ages 2 and 3 years old as the ligaments and tendons in the foot and leg tighten. Having flat feet as a baby is rarely serious, but it may last through adulthood.

Patients with lichen planus died at the same age as psoriatics and the general population, but the diseases they died of were somehow different. Malignant tumors, particularly those of the gut and the bladder, and malignant hemopathies appear to have exceeded the expected prevalence.

Because flat feet cause the weight to be distributed abnormally, other joints and muscles take responsibility for keeping a person upright. As a result, a person can experience back and leg pain that may interfere with daily tasks, exercise, and activities a person enjoys.

A large retrospective study of military recruits reported that those with moderate or severe pes planus (suggested by clinical observation) were almost twice as likely to report a history of intermittent low back pain.