Patella Bone

Table of Contents

Introduction

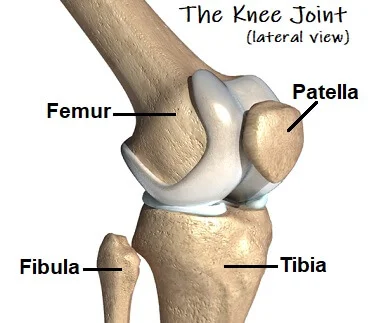

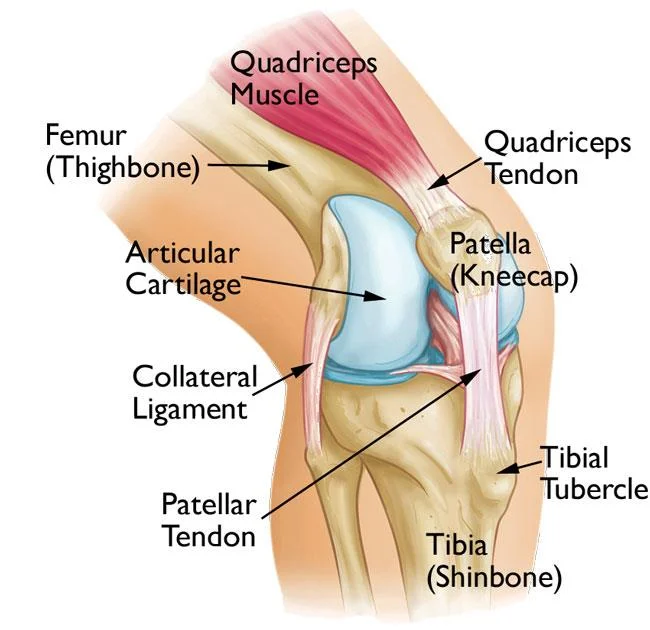

A triangular-shaped, flat bone at the front of the knee joint is the patella, also known as the kneecap. It serves as a point of attachment for the quadriceps muscle group, which is responsible for straightening the knee.

The apex, one of several bony landmarks on the patella, is the pointed end of the bone, the base, the broader end of the bone, and the articular surface, which is the smooth, slightly concave surface that articulates with the femur. The patella also has a posterior surface, which is rough and provides attachment for the patellar tendon.

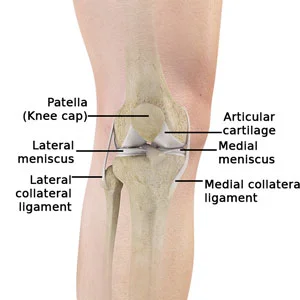

The patellar ligament, which connects the patella to the tibia, and the medial and lateral retinaculum, which are fibrous bands that aid in maintaining the patella in its proper position during movement, are two of the structures that hold the patella in place.

The patella also has a small bone within it called the sesamoid bone, which helps to increase the mechanical advantage of the quadriceps muscle by changing the direction of the muscle’s pull on the knee joint.

The largest sesamoid bone in the human body is the patella, which is encased in a muscle or tendon. A patella made of soft cartilage is present at birth and begins to ossify into the bone around the age of four.

Anatomy of the Patella

The patellar tendon runs inferiorly from the patella bone to the femoral tibial tuberosity. The quadriceps ligament is home to the patella, a significant sesamoid bone with a three-sided cross-over cross-segment. The pisiform carpal bone in the ligament of the flexor carpi ulnaris is another example of a sesamoid bone.

The patellar tendon comes from the patellar apex and attaches to the tibial tuberosity, a bony protrusion on the anterior aspect of the proximal tibia. The patellar tendon may also be referred to by a different name.

A tendon is a piece of connective tissue that holds a muscle and bone together. The term “patellar tendon” is accurate in terms of muscle action. Another point of view to keep in mind is that the patellar “tendon” also known as the patella to tibial tuberosity could be referred to as the patellar ligament because it links two bones together (patella to tibial tuberosity). Tendons are set up to restrict development and the patellar tendon cut-off points flexion of the knee in light of its hard connections.

The patellar tendon is roughly 5 cm long. However, from full extension to 30 degrees of knee flexion, its length mostly increases.

The quadriceps femoris’ medial and lateral segments insert into the upper anterior surface of the tibia on either side of the patella. The medial and lateral patellar retinacula are formed when they join together to form a single capsule. The back part of the patellar tendon is isolated from the knee joint by an infrapatellar fat cushion and a synovial film. The patellar ligament and tibia are also separated by an infrapatellar bursa.

The ability of the patella to lengthen the patellar ligament’s switch arm subsequently allows the quadriceps femoris to apply more muscle compression to the knee’s center for a given amount of time than without the patella.

Structure of the Patella

The patella is a sesamoid bone with the apex facing down, roughly triangular. The inferior (lowest) portion of the patella is the apex. It attaches to the patellar ligament and has a pointed shape.

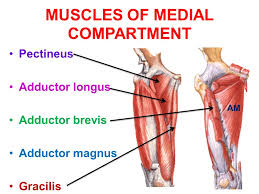

The quadriceps femoris muscle tendon attaches to the base of the patella. A thin line connects the front and back surfaces, and a thicker line connects the center. The patella’s outer lateral and medial borders are where the vastus lateralis and vastus medialis muscles attach, respectively. The vastus intermedius muscle attaches to the base itself.

The rough, coarse, and flattened upper third of the patella’s front serves as the attachment point for the quadriceps tendon and frequently has exostoses. Vascular canaliculi are numerous in the middle third. The apex, which is where the patellar ligament gets its start, is where the lower third reaches its zenith. There are two distinct sections to the posterior surface.

A varying-shaped vertical ledge divides the upper three-quarters of the patella into a medial and lateral facet when it articulates with the femur.

Cartilage covers the adult articular surface and can reach a maximum thickness of 6 mm (0.24 in) in the middle around the age of 30. It covers approximately 12 cm2 (1.9 sq in). Attributable to the extraordinary weight on the patellofemoral joint during opposed knee flexion, the articular ligament of the patella is among the thickest in the human body.

The infrapatellar fat pad, an oily tissue, covers the vascular canaliculi that are present in the lower portion of the back surface.

The function of the Patella

The patella’s primary function is to extend the knee. By increasing the angle at which the quadriceps tendon acts, the patella increases the leverage that it can exert on the femur.

The quadriceps femoris muscle, which contracts to extend or straighten the knee, has a tendon attached to the patella. The prominence of the lateral femoral condyle, which prevents lateral dislocation during flexion, and the insertion of the vastus medalist horizontal fibers stabilize the patella. During exercise, the patella’s reticular fibers also stabilize it.

Blood supply and Lymphatics

The genicular arteries, which are branches of the popliteal artery, provide the patella with its blood supply.

- a superior lateral and medial

- inferior lateral and medial

- a descending and anterior genicular artery

They supply the patella and the knee joint and form a peripatellar anastomosis.

A vast network of blood vessels, which can be divided into extraosseous and intraosseous segments, supplies the patella. The supreme, medial superior and inferior, and lateral superior and inferior geniculate arteries participate with the anterior tibial recurrent arteries to form an extraosseous anastomotic ring around the patella. The mid-patellar vessels, which enter vascular foramina on the anterior surface of the middle third of the patella, and the polar vessels, which enter between the ligamentum patellae’s attachment and the articular surface on the deep surface of the patella, make up the intraosseous vascular supply.

Nerves supply

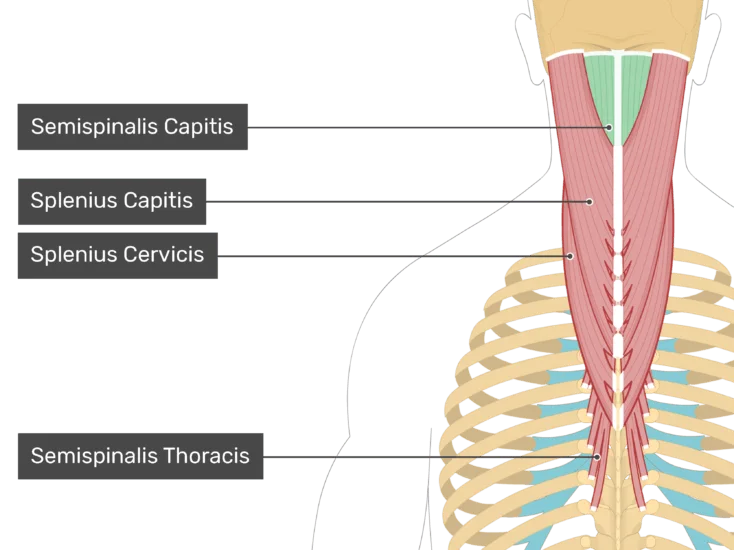

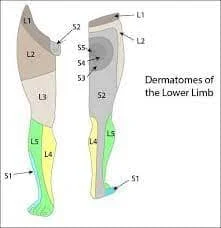

Nerve roots L2 through L5 provide the knee’s anterior cutaneous innervation. The genitofemoral, femoral, obturator, and saphenous nerves are responsible for the knee’s anteromedial innervation. Anterolateral innervation is provided by the lateral femoral and lateral sural cutaneous nerves. There is some disagreement regarding the patella’s intraosseous innervation. The primary intraosseous innervation is derived from a neurovascular bundle located medially, according to several studies; however, other research has shown that superomedial and superolateral nerves are equally important for patellar innervation.

Muscles attachment

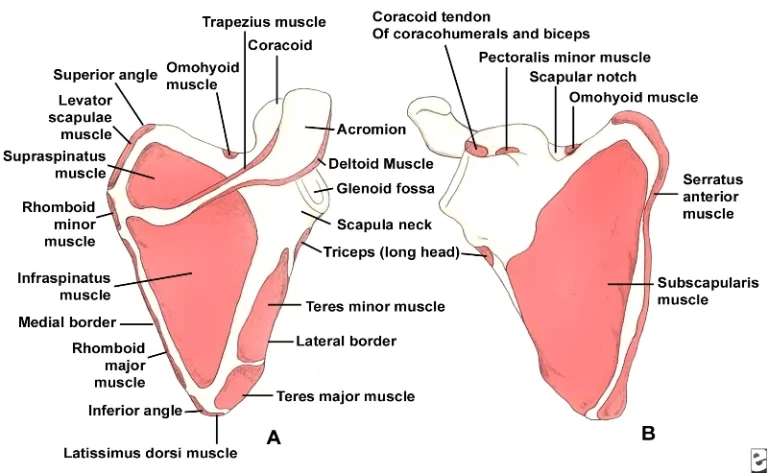

The quadriceps femoris is a large muscle group in the anterior thigh that is responsible for being the primary knee extensor muscle. The rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius, and vastus medialis make up this region. At the superior sides of the patella, these four muscles join the quadriceps tendon, allowing the quadriceps femoris muscles to work together to extend the leg at the knee joint.

Physiologic Variation

The duplex patella, in which the patella is divided into two sections, should be visible in this X-beam. Emarginations, also known as patella emarginates, are common laterally on the proximal edge. When a second cartilaginous layer ossifies at an emargination, double patellas are formed. double patellas were recently remembered to be made by the disappointment of a few solidification places intertwining, yet this hypothesis has since been dismissed. The majority of cases of partite patella occur in men. Patellas can be three-partite or even multipartite.

A varying-shaped vertical ledge divides the upper three-quarters of the patella into a medial and lateral facet when it articulates with the femur. The articular surface can be divided into four main categories:

The medial articular surface is typically smaller than the lateral surface. Sometimes, the sizes of the two articular surfaces are almost the same.

Development of Patella

Between the ages of 3 and 6, the patella develops an ossification center. Two points of solidification join to form the patella when it is fully formed.

During the third week of the embryo’s life, vascular mesenchyme fills the limb buds. It could originate from early body parts. At the end of the fourth week, a small mesenchymal condensation can be seen in the center of the arm bud, and at the beginning of the fifth week, a similar condensation can be seen in the leg bud. This build addresses the main fundamental of the skeleton of the appendage. The tissue forming it might in this way be called scleroblastema. which creates a skeleton covered in membranes. In this, a cartilaginous skeleton is separated, and this thusly is supplanted by the extremely durable rigid skeleton, 3 covering periods, a blastemal, a chondrogenic, and an isogenous.

Clinical importance

Patellar dislocation

Particularly in young female competitors, patellar separations are extremely common. It is a memory of the patella sliding out of its position for the knee, typically at the edge, and may be associated with absolutely outrageous torture and growth. The patella can be followed into the score once more with an increase in the knee, so it occasionally returns to its original isolated position.

Vertical alignment Patella Baja.

A high-riding (superiorly aligned) patella is called a Patella alta. An unusually small patella that grows above and outside of the joint is known as an attenuated patella alta. A low-riding patella is called a baja patella. Extensor dysfunction can occur as a result of a persistent patella baja. The Insall-Salvati proportion assists with demonstrating patella baja on sidelong X-beams and is determined as the patellar ligament length partitioned by the patellar bone length. Patella baja is indicated by a ratio of Insall-Salvati less than 0.8.

Patella fracture

Due to its particularly exposed position, the kneecap is susceptible to injury, and direct knee trauma frequently results in patellar fractures. In most cases, these fractures result in joint bleeding (hemarthrosis), joint swelling, and inability to extend the knee. Unless the extensor mechanism is intact and the damage is minimal, most patella fractures are treated surgically.

Sinding-Larsson Johansson syndrome

This is the delicacy of the peak (lower shaft) of the patella after dull pulling by the patellar tendon. It’s one of juvenile osteochondrosis, and it hurts in the anterior knee. It is most prevalent in children between the ages of 12 and 14 and among those who participate in a lot of sports. Where the quadriceps connects to the patella’s base, the same symptoms have been reported. Osgood-Schlatter disease refers to a similar disease that affects the tibial tuberosity.

Patellar reflex

The contraction of the quadriceps femoris muscle that causes the knee joint to extend is known as the patellar reflex or knee jerk. The myotome responsible for knee extension is L2-4 or the femoral nerve’s lower two divisions. When the patient is instructed to relax their knee, the patella ligament, which is located above and below the tibial shaft, is struck.

The knee should be slightly extended in healthy patients. Some people can have a weaker or stronger patellar reflex; however, this is not always a sign of neurological disease. On the off chance that the knee neglects to respond (missing reflex), it could be an indication of a lower engine neuron sore. In the event that the knee broadens excessively and quickly or powerfully expands, it very well may be an indication of an upper engine neuron sore.

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome

The term “Patellofemoral pain syndrome” (PFPS) refers to pain in the front of the knee and around the patella, also known as the kneecap. It is sometimes referred to as “runner’s knee” or “jumper’s knee” due to its prevalence among athletes, particularly females and young adults, but PFPS can also affect non-athletes. Climbing stairs, kneeling, and performing other everyday activities can be difficult due to the pain and stiffness caused by PFPS.

symptoms

A dull, aching pain in the front of the knee is the most common PFPS symptom. One or both knees may be affected by this pain, which typically develops over time and is frequently triggered by physical activity. Additional typical symptoms include:

Torment during activity and exercises that more than once twist the knee, like climbing steps, running, hopping, or hunching down. Pain in the front of the knee after sitting with your knees bent for an extended period of time, such as in a movie theater or while flying. Pain is brought on by a shift in the playing surface, equipment, or level of activity or intensity. Popping or snapping sounds in your knee while climbing steps or while standing up after delayed sitting.

Home Remedies

Simple home remedies can often alleviate patellofemoral pain. Until your knee pain goes away, stop doing the activities that hurt it. This could mean switching to low-impact activities like riding a stationary bike, using an elliptical machine, swimming that will put less stress on your knee joint, or changing your training routine. Assuming you are overweight, getting in shape will likewise assist with lessening the strain on your knee.

The RICE method

RICE – rest, ice, compression, and elevation.

Rest. Do not put any weight on the knee that is hurting. Ice. Several times per day, apply cold packs for 20 minutes at a time. Ice ought not to be applied to the skin straightforwardly.

Compression. Wrap the knee lightly in an elastic bandage, leaving a hole near the kneecap, to reduce swelling. Ensure that the swathe fits cozily and doesn’t cause extra agony. Elevation. Rest with your knee raised above your heart as frequently as possible.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Notwithstanding action changes, the RICE strategy, and mitigating medicine, your PCP might suggest the accompanying:

Physical therapy. You can increase your strength, endurance, and range of motion with specific exercises. Because these muscles are the primary stabilizers of your kneecap, it is especially important to focus on strengthening and stretching them. If you want to strengthen the muscles in your lower back and abdomen, core exercises may also be recommended.

Orthotics. Shoe augmentations can help change and equilibrium out your foot and lower leg, eliminating tension from your lower leg. Orthotics can be purchased “off the shelf” or made specifically for your foot.

FAQs

Toward the finish of the thigh bone, there is a depression where the kneecap rests. It is held set up by ligaments on the top and base and by tendons on the sides. A layer of cartilage covers the kneecap’s underside. As a result, it can easily move through the thigh bone groove. Age lines the kneecap’s underside. Because of this, it is able to glide along the thigh bone groove.

A small bone on the front of your knee joint is called your kneecap or patella. It is held in place by the trochlear groove and two tendons your patellar tendon and quadriceps tendon that is not attached to any other bone. The patellar tendon connects the tibia (top of the shinbone) to the bottom of the kneecap.

Structure. A thin, compact lamina covers the nearly uniform dense cancellous tissue that makes up the patella. Parallel to the anterior surface are the cancelli immediately beneath it. The remainder of the bone transmits from the articular surface toward different pieces of the bone.

The lateral patella receives blood supply from two primary arteries: the lateral genicular arteries, both superior and inferior. To supply the lower half of the patella, the transverse infrapatellar artery also branches off of the lateral inferior genicular artery.

11 Comments