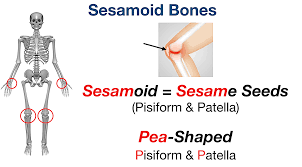

Anatomy of Seasomoid Bone

Table of Contents

What exactly is Seasomoid Bone?

A Sesamoid bone is a bone that is implanted within a tendon or muscle. Its name comes from the Greek word for “sesame seed,” referring to the microscopic size of most sesamoids. These bones frequently develop in reaction to tension or as a natural variety.

The patella is the body’s biggest sesamoid bone. Sesamoids function similarly to pulleys, providing a smooth surface for tendons to glide over, enhancing the tendon’s capacity to transfer muscle forces.

Common variations

- A dorsoplantar image of the foot exhibiting the most prevalent accessory and sesamoid bones.

- One or both of the sesamoid bones under the first metatarsophalangeal joint (of the great toe) can be bipartite (in two parts) or multipartite (in three parts).

- The fabella is a tiny sesamoid bone that is inserted in the tendon of the lateral head of the gastrocnemius muscle behind the lateral condyle of the femur in some animals.

- It is a variation of normal anatomy that affects 10% to 30% of adults.

- The fabella can be bipartite or multipartite.

- The cyamella is a tiny sesamoid bone inserted in the popliteus tendon.

- It is a deviation from normal anatomy.

- It is rarely seen in humans but has been described more often in other primates and certain other animals.

Anatomy of the Seasomoid Bone

- A sesamoid bone is a tiny bone that is usually seen buried inside a muscle or tendon near joint surfaces, ossifying as focal regions and acting as a pulley to relieve tension on that specific muscle or tendon. Sesamoid bones, as opposed to ordinary bones, link to muscles via tendons.

- Because many sesamoid bones are tiny, the term “sesamoid” comes from the Arabic word “sesamum,” which means “sesame.”

- Sesamoid bones are most typically found in the foot, hand, and wrist, with the patella being the biggest and most well-known.

- A person’s sesamoid bones are numerous, with up to 42 supposedly identified in a single individual.

- These bones are frequently developed as a result of increased tension on muscles and tendons, although they can also be typical forms, most usually found in the hand.

- Sesamoid bones reduce tension in muscles and tendons, allowing for greater weight-bearing, and tolerance by dispersing pressures across a muscle or tendon, sparing it from major strain and damage.

- While most sesamoid bones are tiny, they serve an important function in our bodies in terms of leverage, minimizing overall friction, and allowing for our body’s unique biomechanics and range of motion.

Structure and functions

- Many sesamoid bones exist in the body, frequently providing an extra strength advantage to the muscles and aiding tendon stability.

- The patella, for example, improves joint leverage and adds to the extensor qualities of our knee.

- This one-of-a-kind system provides for enhanced knee range of motion and weight-bearing activities. Injuries to the patella severely limit its leverage and extensor capacities; these injuries are frequently caused by trauma and excessive stress.

- Sesamoid bones are classified into two types based on their placement and attachment: type A and type B.

- The synovium is formed when bony surfaces are surrounded by cartilage and integrated inside the hollow. A sesamoid bone and its connections to other tendons create a joint.

- Type A sesamoid bones are found at joints and become part of the joint capsule.

- The hallucis and pollicis sesamoids, as well as the patella, are common instances of this kind, providing additional leverage.

- Type B sesamoid bones are separated by an underlying bursa and overlie a bony protrusion.

- The sesamoid bone of the peroneus (fibularis) longus tendon is an example of a Type sesamoid bone.

- Both forms of sesamoid bones serve distinct purposes and have distinct biomechanical features.

- The fibrocartilaginous sesamoid bone is another form of sesamoid bone.

- This form of sesamoid allows for the preservation of tendon structure while also providing tremendous flexibility from the fibrous component and elasticity from the cartilage tissue.

- The hand and wrist have prominent sesamoid bones in the upper extremities.

- The majority of people have five sesamoid bones in each hand.

- Two sesamoid bones are found in the distal regions of the hand’s first metacarpal bones, especially among the tendons of the flexor pollicis brevis and adductor pollicis.

- The third sesamoid bone is found in the interphalangeal joint.

- In addition, the other two sesamoid bones may be found in the distal portions of the second metacarpal bone and the fifth metacarpal joint.

- The existence of the pisiform bone within the tendon of the flexor carpi ulnaris in the wrist has sparked controversy regarding whether it is a sesamoid bone or a vestigial bone.

- The patella is the biggest sesamoid bone in the lower extremities, located in the knee.

- The fabella (often near the lateral head of the gastrocnemius), cyamella (within the popliteus tendon), os perineum (within the peroneus longus tendon), and hallux sesamoid pair (one on each side of the first metatarsal bone of the foot) are other lower limb sesamoids that can be seen as normal variants in humans.

- The lenticular process of the incus, also known as the fourth ossicle of the middle ear, is another sesamoid bone within the ear.

Embryology

- Sesamoid bone production is connected to the body’s normal growth as well as numerous pressures exerted on the body.

- Most sesamoid bones begin as cartilaginous nodules and progress to endochondral ossification throughout the prepubertal years.

- During adolescence, more calcification occurs, with sesamoid bones developing sooner in females.

- A lack of sesamoid bone development frequently suggests a puberty delay and can be used to track the progression of puberty.

- While the majority of sesamoid bones appear to form in response to diverse stressors, the patella is present in all humans.

- Its growth is important in the structure and function of the lower extremities, allowing researchers to examine sesamoid bone formation.

- When compared to other sesamoid bones, the patella is distinguished by its comparatively bigger size and stable existence in humans.

- The patella develops during the first trimester of pregnancy, after the chondrification of the femur and tibia, with the early patella evident as a continuous band of fibrous tissue.

- The embryological patella gets chondrified and inserted into the quadriceps by the 9th week of gestation as it grows inside the ring of fibrous tissue.

- The patella is completely cartilaginous by 14 weeks of gestation and mimics the adult patella anatomy by 23 weeks of gestation.

- The patella continues to expand rapidly until the end of the second trimester when it slows to match the rest of the growing fetus.

- Ossification occurs in the patella throughout childhood and continues until early adolescence, as it does in other sesamoid bones.

- At the time of the pubertal years, the patella evolves confluent with the quadriceps, stabilizing into the adult patella.

Lymphatics and Blood Supply

- Any bone’s blood flow and lymphatics are critical to its sustenance and growth.

- Given the variety in the growth of most sesamoid bones, blood supply, and lymphatics are mostly determined by the position and development of the individual bone.

- These bones have a restricted blood supply and are prone to avascular necrosis, which can lead to problems.

- The patella, on the other hand, is an outlier due to its importance, size, and constant function in the human body.

- Its early growth during pregnancy, as well as its important role in sustaining the lower extremities, need a plentiful blood supply.

- The patella is nourished by a vast extraosseous and intraosseous network of blood veins.

- The extraosseous network of blood supply is surrounded by a vascular anastomotic ring formed by the genicular arteries (superior medial, lateral, descending, inferior medial, lateral, and anterior genicular) and the anterior tibial recurrent arteries.

- The intraosseous blood supply is divided into two systems: mid-patellar vessels that reach the anterior surface of the patella and polar vessels that penetrate the deep surface of the patella.

- The extraosseous and intraosseous vasculature work together to guarantee the patella’s robust blood supply.

- While the patella is the only sesamoid bone with a variable blood supply, others, such as the hallux sesamoids, might present with a variable blood supply.

- A study of 29 dissected human feet revealed that the medial plantar artery branches into the hallux’s digital plantar arteries before giving rise to the sesamoid arteries.

- This interpretation in anatomy demonstrates critical in evaluating anomalies between various individuals and additional understanding of the potential avascular necrosis in sesamoid bones.

- Other vasculature of sesamoid bones incorporates the palmar metacarpal arteries that emerge from the deep palmar arch providing the 1st and 2nd metacarpals.

- The pisiform acquires its blood supply from the ulnar artery.

- The ossicular branch of the anterior tympanic artery provides the lenticular process of the incus.

- In extra, the fabella acquires its blood supply mainly from the articular external branches of the popliteal artery.

- Likewise, the cyamella acquires its arterial supply from the medial inferior genicular branch of the popliteal artery.

- Most frequently, the os peroneum obtains blood from the peroneal and anterior tibial arteries.

- This difference in architecture is important for comparing abnormalities between persons and identifying probable avascular necrosis in sesamoid bones.

- The palmar metacarpal arteries, which come from the deep palmar arch and supply the first and second metacarpals, are another kind of sesamoid bone vasculature.

- The pisiform is supplied with blood via the ulnar artery.

- The lenticular process of the incus is provided by the ossicular branch of the anterior tympanic artery.

- Furthermore, the fabella is predominantly supplied by the articular exterior branches of the popliteal artery.

- Similarly, the cyamella receives its vascular supply from the popliteal artery’s medial inferior genicular branch.

- The peroneal artery and anterior tibial artery are the most common blood vessels that supply the os peroneum.

Nerves

- The innervation of a sesamoid bone is determined by its anatomical position.

- The patella, for example, has considerable innervation, with separate nerves controlling the anterior, medial, and lateral parts of the knee.

- The cutaneous area of the anterior knee is innervated by nerve roots L2 to L5.

- Meanwhile, the genitofemoral, femoral, obturator, and saphenous nerves feed the anteromedial portion of the knee.

- The lateral femoral and lateral sural cutaneous nerves innervate the anterolateral portion of the knee.

- These nerves work together to generate a dense innervation network to the patella for its particular biomechanical function.

- The plantar digital nerves innervate other sesamoid bones, such as the hallux sesamoid.

- The presence of nerves near sesamoid bones might lead to clinical problems.

- The pisiform is distinctive in that it also produces the Guyon canal, which allows the ulnar nerve to pass through.

- Any pisiform bone fracture is related to ulnar nerve compression and its consequences.

- Similarly, an os peroneum fracture has been linked to sural nerve entrapment.

- The presence of the fabella bone near the gastrocnemius can cause common fibular nerve palsy, necessitating a patellectomy if symptoms continue despite conservative treatment.

- Other sesamoid bones, such as the cyamella, are uncommon, and their innervation is unknown.

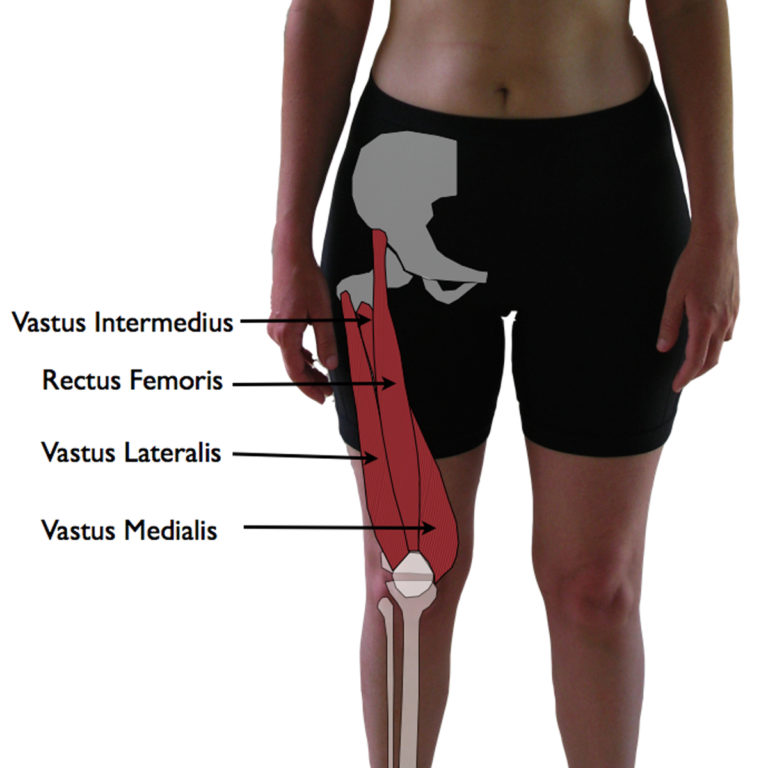

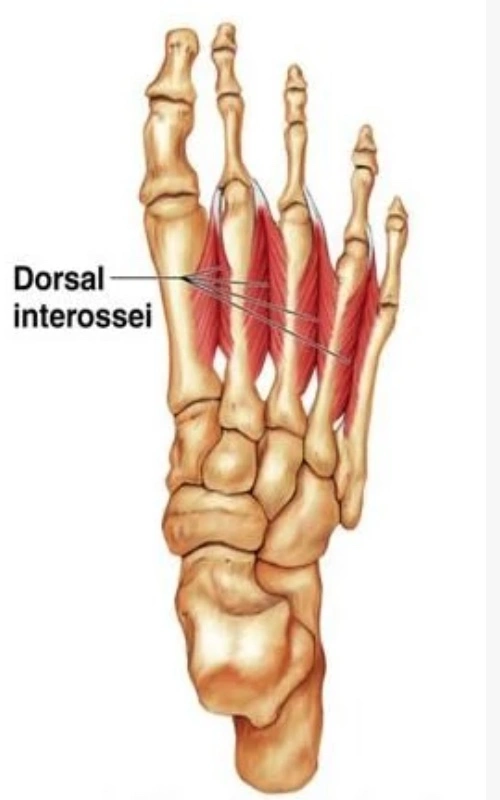

Muscles

- Whereas most bones are joined at joints, sesamoid bones are distinct in that they are not attached to other bones.

- Instead, they are situated within muscles and are frequently linked by tendons.

- The patella’s function and relationship to other muscles have been well investigated, and it serves as the foundation for addressing sesamoid bones with muscle groups.

- Because of its unique location in the lower extremities, the patella may operate as a pivot point, allowing the quadriceps to handle larger loads with less friction.

- The patella, which connects the quadriceps tendon to the patellar ligament, enables flexion and extension of the lower limbs.

- The quadriceps tendon can withstand maximum stresses several times those of an average human.

- This bent position necessitates a greater use of the connecting function.

- The patella shifts load-bearing to the patellofemoral and tendon-femoral connections when the knee moves from flexion to extension.

- When the knee is fully extended, the patella is the only extensor to make contact with the femur, producing a biomechanical advantage akin to a pulley.

- The vital relationship between the quadriceps tendon and the patellar ligament via the patella provides for the knee’s large and unique range of motion by transferring stresses.

- However, not all sesamoid bones serve this purpose.

- The fabella bone, a frequent sesamoid bone variant found near the gastrocnemius and articulating with the lateral femoral epicondyle, can occasionally produce problems like the fabella pain syndrome.

Physiological variation

- Sesamoid bones are prevalent in humans, with some bones, such as the patella, present in everyone and essential for lower extremity function.

- Because of its persistent presence, size, and significance in humans, the patella is an outlier among sesamoid bones.

- While the patella is present in all individuals, it has been demonstrated that it does not form completely in paralyzed embryos due to a lack of mechanical stress, emphasizing the importance of genetics as well as contemporaneous biomechanical stress in the development of a sesamoid bone.

- Lesser-known sesamoid bones occur as variations and can arise spontaneously as a result of extrinsic and intrinsic influences.

- Mechanical forces, biomechanics, and skeletal geometry all play a role in the formation of sesamoid bones. Intrinsic genetic factors also play an important role.

- One research found that the fabella sesamoid bone and the os peroneum sesamoid bone frequently appeared together in people.

- These sesamoid bones are smaller and less common. Inconclusive research also exists on the numerous elements that influence the development of sesamoid bone variants.

- Genetics and mechanical factors both play essential roles in the development of common sesamoid bones like the patella and variations like the fabella and os perineum.

- Individual differences in sesamoid bone formation exist even within the hand.

- Two sesamoid bones were found at the thumb metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, however, 30% of the individuals investigated had differences in the morphology and fusion lines of the sesamoid bones.

- When compared to the joints of the other fingers, the thumb MCP joints consistently exhibited two sesamoid bones.

- Similarly, 60% of people had an index finger MCP sesamoid bone, whereas 59% had a 5th finger MCP sesamoid bone.

- Sesamoid bones differ in humans based on their existence, quantity, size, and form, with both external and internal factors influencing them.

Considerations for Surgery

- It is essential to be aware of the anatomical variances of sesamoid bones when undertaking procedures.

- While patellar procedures, such as total knee arthroplasty, are prevalent, medical imaging plays an important role in pre-operative diagnosis, surgical technique, and postoperative follow-up.

- It is also important to cut the medial to the patella, reflecting the patella laterally to access the patellofemoral joint.

- Similarly, imaging is used to see different structures within the knee during procedures involving the various ligaments of the knee.

- Because of its persistent existence and importance, the patella remains the exception in the study of sesamoid bones.

- Sesamoid excision has been researched in athletes with a sesamoid bone injury to see if it affects an athlete’s skill.

- According to the study, over 80% of athletes who received a sesamoidectomy were able to return to sports within five months.

- The Hallux sesamoid is another widely researched sesamoid surgery.

- A sesamoidectomy was investigated for the possibility of improving outcomes after a successful union of a hallux sesamoid fracture.

- According to the findings of the study, sesamoidectomy gave superior pain relief and allowed for a return to regular activities after 12 weeks.

- Although avascular necrosis of the sesamoid may often be handled medically, a sesamoid excision resulted in total pain alleviation and increased patient satisfaction.

- Whereas a sesamoid bone seldom caused substantial discomfort or anguish, any fracture or damage to a sesamoid bone benefited considerably from excision rather than union treatment.

- If appropriate imaging is not readily accessible in an emergency circumstance, an unanticipated sesamoid bone provides a distinct obstacle in procedures targeting that specific location.

- If a sesamoid bone is suspected, surgeons must be aware of various anatomical variations and their interactions with the local anatomy.

- If traditional surgical procedures and approaches do not allow for an unanticipated sesamoid bone, special care must be given.

Clinical Importance

- Sesamoid bones are clinically important in our everyday biomechanics and range of motion, from their growth during pregnancy to their day-to-day function inside the body.

- Consistent, solid sesamoid bones, such as the patella, allow the lower extremities to unload stresses for ambulation and to sustain more weight.

- Without the patella, frequent concerns would include knee joint instability, limited range of motion, and difficulty straightening the leg.

- This adaption has enabled humanity to evolve over millennia.

- While the patella remains a constant example across the body, keyboard pianists have revealed modifications of sesamoid bones.

- The study found that musicians have higher sesamoid bone volume in their hands; an abnormally shaped sesamoid is more common in female musicians.

- The frequent usage of a musician’s hands and the resultant growth in sesamoid bone volume demonstrate that the body continually adjusts to the varied stresses encountered.

- Sesamoid bones play a vital role in the body, permitting regular actions many take for granted.

- Studies persist in exploring the many other sesamoid bones and their function in the human body.

FAQ

Lower extremity flexor hallucis brevis and fibularis (peroneus) longus sesamoid bones are located near the cuboid bone and under the first metatarsal head, respectively. near the medial cuneiform bone of the tibialis anterior. the medial side of the talar head, where the tibialis posterior tendon is located.

Some tendons bridge the ends of long bones to form a kind of bone called a sesamoid bone. Puberty causes the sesamoids to ossify, and delayed ossification may signal a delayed start to puberty. The patella, located in the quadriceps tendon near the knee, is one example of a sesamoid bone in the human body.

Small, flat bones known as sesamoid bones are found inside muscles or tendons. The connective tissue present in tendons and ligaments is used to create them.

The tendons of the wrists, knees, and feet frequently include these tiny, spherical bones. The goal of sesamoid bones is to shield tendons from stress and abrasion. An illustration of a sesamoid bone is the patella, sometimes known as the kneecap.

Five sesamoid bones are typically present in each hand. One at the thumb’s interphalangeal joint, two at the thumb’s metacarpophalangeal joint, one at the index finger’s radial metacarpophalangeal joint, and one at the little finger’s ulnar metacarpophalangeal joint.

References

Wikipedia contributors. (2023a). Sesamoid bone. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sesamoid_bone

Yeung, A. Y. (2023, April 4). Anatomy, sesamoid bones. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK578171/