Large Intestine

Table of Contents

Overview

The large intestine is the most important element of your digestive system’s complicated, tube-shaped gastrointestinal (GI) tract, where food finally exits your body.

Intestinal waste from food gets expelled at the anal canal, where it ends after reaching the small intestine. The large intestine converts food waste into stool, whereby the body removes when you poop. The large intestine in humans averages half a meter (5 feet) long overall, or approximately half of the complete length of the gastrointestinal tract.

Structure of Large Intestine

The final section of the digestive system is the colon of the large intestine. It is where the fermentation of unabsorbed material by the gut microbiota acquired proceeds and excludes water and salt from solid wastes before they are eliminated from the body. The colon does not have an important influence on food and nutrient absorption, unlike the small intestine.

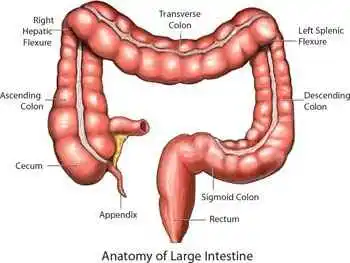

Sections

The colon, which is the longest component of the large intestine in mammals, incorporates the appendix, the rectum, the anal canal, and the cecum. The colon can be divided into four sections: the sigmoid colon, descending colon, transverse colon, and ascending colon. The colic flexures are in which those areas turn. Either the colon’s elements are positioned intraperitoneally or in the retroperitoneum, which is behind it.

Retroperitoneal organs remain firmly in place because, generally speaking, the peritoneum does not completely cover them. Although the peritoneum completely encompasses intraperitoneal organs, these tissues are mobile. The colon’s cecum, appendix, transverse colon, and sigmoid colon are intraperitoneal, but the ascending, descending, and rectum are retroperitoneal. This matters in that it influences which organs are simple to access during procedures like laparotomies.

Cecum and appendix

The appendix, which emerges embryologically from the cecum and appears to be an element of the gut-associated lymphoid tissue, is not involved in digestion. The cecum is the first stage of the large intestine and is in digestion.

The original intent of the appendix is not, however depending on some writers of note, it serves as a repository for a sample of the gut microbiota and may rebuild the microbiota in the colon if it becomes damaged during an immunological response. It has also been demonstrated that the appendix contains a significant amount of lymphatic cells.

Ascending colon

The rising colon is the most prominent of the large intestine’s four distinct sections. It is attached to the small intestine via the cecum, a segment of the colon. For aquired eight inches (20 cm), the ascending colon continues upward via the abdominal cavity against the transverse colon.

Removing water and other vital substances from trash and reusing them is one of the colon’s primary jobs. This extraction process originates in the ascending colon, where the waste material travels after passing through the ileocecal valve and leaving the small intestine. Peristalsis pumps the removed particles upward in the transverse colon.

Transverse colon

The section of the colon that proceeds from the splenic flexure, also known as the left colic (the turn of the colon by the spleen), to the hepatic flexure, also characterized as the right colic (the turn of the colon by the liver), is called the transverse colon. A sizable peritoneal fold termed the larger omentum binds the transverse colon to the stomach, causing it to drop outside. A mesentery termed the transverse mesocolon attaches the transverse colon to the posterior abdominal wall on the posterior side.

The middle colic artery, a branch of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), distributes blood to the proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon, while the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) distributes blood to the last third. Ischemia-sensitive tissue lies in the “watershed” portion that stands between these two blood supplies and signifies the embryologic growth between the midgut and hindgut.

Descending colon

The segment of the colon that reaches from the splenic flexure to the start of the sigmoid colon is known as the descending colon. Retroperitoneal in two-thirds of the human population. The left colic artery is the entry point for the arterial supply. While it exists farther along the gastrointestinal tract than the proximal gut, the descending colon is often referred to as the distal gut. This particular region has a highly thick gut flora.

Sigmoid colon

The section of the large intestine that passes before the rectum and after the descending colon has the name the sigmoid colon. A sigmoid is an S-shaped formation (see sigmoid; additionally the sigmoid sinus).

Blood from a variety ( frequently two to six) of the IMA’s sigmoid arteries serves the sigmoid colon. The superior rectal artery begins where the IMA ends.

Rectum

It is an area in the body where waste products accumulate while a person is ready to pass them. The rectal region can be compromised by several kinds of ailments.

Function of Large Intestine

The food’s remainders nutrients and water are absorbed by the large intestine, which then pushes the indigestible particles to the rectum. Vitamins formed by colonic bacteria, such as thiamine, riboflavin, and vitamin K, are metabolized by the colon (specifically essential as daily ingestion of vitamin K is typically not enough to maintain useful blood coagulation). It compacts waste and preserves it in the rectum until it is expelled through defecation down the anus.

The appendix has a mysterious role in immunity since it contains a tiny quantity of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. However, considering it includes endocrine cells that create peptide hormones and biogenic amines vital to homeostasis during early growth and development, the appendix is recognized to be significant in fetal life.

Blood supply

The branching of the inferior and superior intestinal arteries (The intramuscular area and accounting through the SMA to be precise) provides the colon with its circulatory system supply. Historically, it was believed that a structure that connected the proximal SMA to the proximal IMA was the Riolan arc or the Moskowitz meandering mesenteric artery.

In the situation that either vessel was obstructed, this variable construction would be crucial. At least one literature review still casts doubt on the existence of this vessel, and some specialists are asking for the removal of this terminology from any future medical literature.

Lymphatic drainage

The ileocolic and superior mesenteric lymph nodes, which discharge into the cisterna chyli, receive lymphatic the exit from the ascending colon and the proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon.

The inferior mesenteric and colic lymph nodes collect the lymph from the distal third of the transverse colon, the descending colon, the sigmoid colon, and the upper rectum. The internal ileocolic nodes acquire drainage from the lower rectum to the anal canal above the pectinate line. The superficial inguinal nodes capture the anal canal’s drains below the pectinate line.

Nerve supply

The diaphragm’s oesophageal gap permits the vagus nerve (CNX) to enter the abdominal cavity and provide the large intestine with parasympathetic innervation. The parasympathetic supply of the large intestine is likewise improved by the pelvic splanchnic nerves (S2-4).

Clinical significance

- Diverticulitis: An inflammation of the small pockets lining the various sections of the intestine is commonly referred to as diverticulitis. Constipation, diarrhea, bloating, and stomach pain are significant side effects. Life-threatening infections can be pushed on by inflammation. Likewise, Surgery might be necessary to remove the injured intestine.

- Ulcerative Colitis: It is an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that results in ulcers (sores) and inflammation of the digestive tract. The lining of the large intestine, also referred to as the colon, and the rectum are both damaged by ulcerative colitis.

- Proctitis: Rectal-anus inflammation is the diagnosis of proctitis. Other symptoms include itching, rectal bleeding, and loose stools. Proctitis may be brought on by viruses, bacteria, inflammatory bowel disease, or radiation therapy. Proctitis can frequently be treated with medication and lifestyle modifications.

- Crohn’s Disease: The entire digestive system, from the initial stage of the GIT to the completion, can be impacted by Crohn’s disease, an inflammatory bowel condition. Essentially there is no cure for Crohn’s disease, medicine may relieve symptoms and improve your quality of life.

- Rectal Ulcers: Sores or cracks in the lining of the rectum are identified as rectal ulcers. They typically present with symptoms involving vomiting, loose stools, and sensations in the abdomen.

- Hemorrhoids: Haemorrhoids are lumps or masses of tissue in the anus and rectum which include swollen blood vessels. They approximate leg varicose veins. Severe bleeding and discomfort frequently occur as side effects of hemorrhoids.

Large intestine Treatments

- Transanal endoscopic microsurgery: Retroctal and anus abnormalities are minimally repaired by applying transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Abdominal or rectum pain, hemorrhage, and inflammatory bowel disease are all cured by transanal endoscopic microsurgery.

- Laparoscopic rectopexy: Using a surgical technique considered laparoscopy, the doctor can access the insides of the abdomen and pelvis without causing large skin incisions. For the treatment of the large intestine, this may also be referred to as keyhole surgery or minimally invasive surgery.

- Rectocele repair: Vaginal rectum bulges have the term rectocele. Bowel blockage and incontinence might arise.

- Colectomy: A colectomy is a surgical operation where all of the colon is removed, or just an inch of it. A colonectomy can be completed laparoscopically or openly.

- Colostomy: If there is a blockage in the colon that cannot be practically removed, a colostomy may be required. This could be caused by Crohn’s disease, cancer, or another health problem.

large intestine Medicines

- Steroids for reducing inflammation of the large intestine: The most frequent ways for distributing steroids are by injection or pill. They can be used to manage rapid flare-ups or to regularly stop them from arising again.

- Analgesics for pain in the large intestine: Numerous muscle relaxants can be used to treat large intestine stiffness. The prevalent and successful procedures are antispasmodics, which diminish spasm symptoms, and anti-inflammatories, which increase colonic inflammation.

- Muscle relaxants for stiffness in the large intestine: For the treatment of stiffness in the large intestine, many kinds of muscle relaxants are available. Antispasmodics, which minimize spasm indications, and anti-inflammatories, which diminish colon inflammation, are the most often used and reliable treatments.

- Antibiotics for infection in the large intestine: Large intestine infections might be treated with a wide range of medications.

FAQs

What is the significance of the big intestine?

The primary tasks of the large intestine are to create and absorb vitamins, absorb water and electrolytes, and form and convey feces in the opposite direction of the rectum for availability.

The large intestine occupies where?

From your waist down, the large intestine is found in the lower abdominal cavity. Its tail originates at the anal canal, whereas it generates an irregular controversy mark-like pattern right through the small intestine.

How is the big intestine cleaned?

Enhancing your water intake, adding more fiber to your diet, and planning regular exercise sessions are the healthiest ways to clear your colon. Aim for at least three flushes per week. Consult a physician about remedies for laxative usage and constipation reduction.

What part of the significant intestine is the most so important?

You may have heard individuals describe the colon differently. The colon is the main portion of the big intestine. Further, the colon becomes the primary area for the absorption of water and, when required salts.

References

- NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms. (n.d.). Cancer.gov. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/large-intestine

- Professional, C. C. M. (2024a, May 1). Large intestine (Colon). Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/22134-colon-large-intestine

- Wikipedia contributors. (2024a, September 5). Large intestine. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Large_intestine

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2024, September 21). Large intestine | Definition, Location, Anatomy, Length, Function, & Facts. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/large-intestine

One Comment