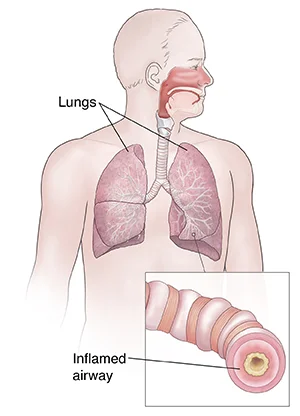

Bronchospasm

- Bronchospasms occur when the muscles that line your bronchi (airways in your lungs) tighten. This outcome in wheezing, coughing, and other symptoms. Many things can cause bronchospasm, including asthma, and it is usually managed with bronchodilators.

- It is a tightening of the muscles that line the airways (bronchi) in your lungs. When these muscles tighten, your airways are small.

- Narrowed airways do not let as much air come in or go out of your lungs. This limits the amount of oxygen (O2) that enters your blood and the amount of carbon dioxide that leaves your blood.

- Bronchospasm often harms people with asthma and allergies. It contributes to asthma symptoms such as wheezing and shortness of breath.

Table of Contents

What is bronchospasm?

- The airways that connect your windpipe to your lungs are known as bronchi. Often the muscles that line your bronchi tighten and cause your airways to narrow. This is known as bronchospasm, and it limits the amount of oxygen your body receives.

What does bronchospasm feel like?

- Bronchospasm can be scary because it feels like you can not get enough air. If you have never had bronchospasm before, your first experience can be especially terrifying. If you develop sudden or serious symptoms of bronchospasm, such as chest pain or difficulty catching your breath, or wheezing, you should go to your nearest emergency room for treatment.

Who gets bronchospams?

- Bronchospasms can happen to anyone, but they are most common in people with allergies, asthma, and other lung conditions. Additionally, young children and adults over the age of 65 are more likely to create bronchospasms.

How common is bronchospasm?

- Bronchospasm is quite usual. It is associated with many different conditions, including asthma, emphysema, COPD, and lung infections.

What is the difference between bronchospasm, laryngospasm, and asthma?

- These conditions are all different, yet they all affect your breathing.

Laryngospasm vs bronchospasm

- While bronchospasm affects your bronchi, laryngospasm harms your vocal cords. With laryngospasm, your vocal cords immediately close up when you take a breath, blocking the flow of air into your lungs. This rare condition can be scary, yet it usually goes away on its own within one or two minutes.

Bronchospasm vs asthma

- Bronchospasm is a symptom of asthma and another medical condition. People with asthma can get bronchospasm, yet not everyone with bronchospasm gets asthma. Both conditions are the outcome of irritated or inflamed airways.

What are the symptoms of bronchospasm?

- When you have bronchospasm, your chest feels tight, and it can be hard to get your breath. Bronchospasm symptoms can be frightening and may move on suddenly. People with the condition often feel like they can not catch their breath.

Other bronchospasm symptoms involve:

- Tightness in your chest

- Shortness of breath

- Wheezing

- Coughing

- Tiredness

- Dizziness.

What causes bronchospasm?

Anytime your airways are annoyed or swollen, it can cause bronchospasm. Any swelling and irritation in your airways can cause bronchospasm. This condition commonly harms people with asthma. Asthma is the most common cause of bronchospasm, yet there are several other things that can result in the condition, including:

- Bacterial, viral, or fungal contamination of the lungs or airways

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Dust, pollen, pet dander, and another allergen

- Exercise (exercise-induced bronchospasm)

- Chemical fumes or another irritant (such as perfumes)

- Cold temperatures

- Smoking or vaping,

- General anesthesia is used in surgery.

- Bronchospasm is a symptom of several various conditions. However, just because you have one of the conditions listed above, it does not necessarily mean that you will develop bronchospasm.

- In very rare instances, bronchodilators usually used to treat bronchospasm can actually make the condition worse. This is known as paradoxical bronchospasm. If this occurs, you should stop using your bronchodilator immediately and look for alternative treatment.

How is bronchospasm diagnosed?

- Your healthcare provider (doctor) can diagnose bronchospasm. They will perform an examination and ask about your symptoms and medical history. In some cases, your provider (doctor) may refer you to a pulmonologist (a specialist who treats lung disease).

- To diagnose bronchospasm, you can look at your primary care doctor or a pulmonologist (a doctor who treats lung diseases). The doctor will tell you about your symptoms and find out if you have any history of asthma or allergies. Then they will listen to your lungs as you breathe exhale and inhale.

- You may have lung function tests to calculate how well your lungs work.

What tests will be used to diagnose bronchospasm?

Your provider (doctor) may recommend certain assessments to determine how well your lungs are functioning. These tests may involve:

- Pulse oximetry: A device is placed on your finger or ear to measure how much oxygen (O2) is in your blood.

- Spirometry: A spirometer is a device that calculates the force of air as you breathe in and out of a tube.

- Lung volume assessment: This tells your provider (doctor) how much air your lungs can hold.

- Lung diffusion capacity: During this test, you breathe into a tube to determine how well oxygen is transferred or diffused connecting your lungs and your blood.

- Arterial blood gas tests: This test calculates the amount of oxygen and carbon dioxide in your blood. It also calculates the pH level of your blood.

- Escaping voluntary hyperventilation: Your healthcare provider (doctor) may use this test to check for exercise-induced bronchospasm. During this assessment, you breathe in a mixture of oxygen (O2) and carbon dioxide (CO2), which mimics breathing during exercise. If it has negative contact in your lungs, then you probably have exercise-induced bronchospasm.

- In addition to the breathing tests, your healthcare provider (doctor) may also take imaging tests to look for infections or other lung problems. These tests could involve chest X-rays and CT scans.

How do you treat bronchospasm?

- Bronchospasm treatment commonly starts with bronchodilators. This medication is available in different forms, involving inhalers, nebulizer solutions, and tablets. In more severe cases, your healthcare provider (doctor) may recommend steroids to reduce inflammation in your airways.

Short-acting bronchodilators

- Short-acting bronchodilators provide quick “rescue relief” for bronchospasm symptoms. These medications can widen your airways in a matter of minutes and the effects last up to six (6) hours. Common short-acting bronchodilators involve albuterol and levalbuterol.

Long-acting bronchodilators

- Long-acting bronchodilators decrease your risk of bronchospasms in the future. With the exception of formoterol, they are not useful as rescue inhalers because they do not offer immediate relief. While the effects take longer to kick in, they last for up to 12 (twelve) hours. Common long-acting bronchodilators involve salmeterol, formoterol, and vilanterol.

- Other forms of long-acting bronchodilators involve anticholinergics which are available in short-acting (e.g ipratropium) and long-acting forms of inhalers (e.g tiotropium, umeclidinium, and aclidinium).

Steroids

- Steroids assist reduce inflammation in your airways. These medications are sometimes inhaled. But if your bronchospasm is serious, steroids may be given in pill form or through an IV line (intravenously).

Physiotherapy Treatment

Aims of Chest Physiotherapy

The purpose of chest physiotherapy are:

- To facilitate the transfer of retained or profuse airway secretions.

- To optimize lung compliance and the ventilation-perfusion ratio/ increase gas exchange.

- To reduce the work of breathing.

- Increase exercise tolerance

- Cure secondary complications.

The Physiological Mechanism of Airway Clearance

- Normal Clearance: A normal clearance needs an open airway, a functional mucociliary escalator, and an effective cough. Airways commonly are kept open by structural support mechanisms and kept clear by the proper function of their ciliated mucosa. The normal human bronchial tree is lined by a thin (5 micrometers) layer of mucus which is motioned over the airway surface by the mucociliary escalator. The ciliated epithelium which lines the airways is responsible for the constant flow of mucus over the airway surface to the upper respiratory tract. The mucus is moved via a coordinated movement of ciliary motion toward the trachea and larynx, where excess secretions can be swallowed or expectorated.

- An effective cough is a should for normal airway clearance.

- Cough is one of the most main protective reflexes. By ridding the bigger airways of excessive mucus and foreign matter, the cough assists the normal mucociliary clearance and assists ensures airway patency. There are four (4) distinct phases to a normal cough: irritation, inspiration, compression, and expulsion.

- Abnormal Clearance: The flow of air through the tracheobronchial tree and its interactivity with the mucus lining is complex because of the branching geometry of the airways, collapsible airway walls, constantly changing the velocity of airflow, and differing viscoelastic properties of mucus. This physiology of flow in the liquid line airway is known as a two-phase gas-liquid flow. In endobronchial diseases, the mucus layer may exceed five mm in thickness and ciliary clearance becomes ineffective. Two-phase flow now becomes a main mechanism of clearance, and at a particular combination of airflow, mucus viscosity, and thickness there is a very strong gas-liquid interaction which 1st exacerbates the pressure decrease and then detaches liquid from the airway wall. this conducts to the narrowing of the lumen of the tube causing a much greater resistance, thus affecting airway clearance.

- One of the mechanisms by which cough harms sputum clearance in endobronchial diseases is two phases of gas-liquid flow: the transfer of momentum and energy from the high-speed flow of air to the mucus that lines the bronchi. The high transmural pressure produced during cough conducts to dynamic compression of the airway inhibiting mucociliary clearances. Thus, the forced expiratory technique (FET) was introduced to resolve this problem.

Classification

- There are different physiotherapy treatments incorporated within chest physiotherapy. Chest physiotherapy techniques can be categorized as conventional, modern, or instrumental techniques based on making research.

Conventional Techniques

- Conventional chest physiotherapy is also called traditional chest physiotherapy. It was advocated 1st in 1915. It includes manual handling techniques to facilitate mucociliary clearance. Postural drainage along with percussion and vibration ( PDPV) was before widely named Chest Physiotherapy.

- After, coughing exercises and forced expiratory techniques (huffing) were included within it. Postural drainage along with percussion and vibration (PDPV) with huffing has shown an effective outcome.

- It can be self-administered or performed with the assistance of other people (a physiotherapist, parent, or caregiver). Postural drainage along with percussion and vibration (PDPV) works better if applied with bronchodilator therapy.

Postural drainage

- Postural drainage (PD) includes positioning a person with the assistance of gravity to aid the normal airway clearance mechanism. Postural drainage positioning differs based on specific segments of the lungs with a large number of secretions. Postural drainage is the drainage of secretions, by the effect of gravity, from 1 or more lung segments to the central airways (where they can be removed by a cough or mechanical aspiration).

- Each position consists of placing the select lung segment(s) superior to the carina. Positions should commonly be held for 3 (three) to 15 minutes (longer in special situations). Standard positions are adjusted as the patient’s condition and tolerance permit.

- Previous to determining the postural drainage position, it is very main to auscultate the lungs and identify the lung segments where added sound (Crepitus, Ronchi) is heard. Postural drainage (PD) can be facilitated with percussion and vibration in the postural drainage (PD) position.

Percussion

- Percussion is referred to as cupping, clapping, and tapotement. The purpose of percussion is to intermittently put kinetic energy into the chest wall and lungs.

- This is accomplished by rhythmically striking the thorax with a cupped hand or mechanical device straight over the lung segment(s) being drained.

Vibration

- Vibration includes the application of a fine tremorous action (manually performed by pressing in the direction that the ribs and soft tissue of the chest move during expiration) over the draining area.

- In this technique, a fast vibratory impulse is transmitted through the chest wall from the flattened hands of the therapist by isometric alternate contraction of the forearm flexor and extensor muscles, to loosen and dislodge the airway secretions.

Coughing

- Coughing includes directed coughing and different assisted coughing techniques.

Forced Expiratory Technique (FET)

- Forced expiratory techniques include diaphragmatic inspiration, relaxing the scapulohumeral region, and expiring forcefully from mid to decrease lung volumes whilst maintaining an open glottis (“huffing” exercises).

- It is more operative than coughing.

Indication of Conventional techniques

Postural drainage positioning

- Inability or reluctance of the patient to exchange body position. (eg, mechanical ventilation, neuromuscular disease, drug-induced paralysis).

- Poor oxygenation allianced with the position (eg, unilateral lung disease).

- Potential for or presence of atelectasis.

- Presence of artificial airway.

Postural drainage along with percussion and vibration (PDPV)

- Difficulty clearing secretions with expectorated sputum production bigger than 25-30 mL/day (adult).

- Evidence or suggestion of kept secretions in the presence of an artificial airway.

- Presence of atelectasis caused by or douted of being caused by mucus plugging.

- Diagnosis of diseases like cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis, or cavitating lung disease

- Presence of foreign body in the airway.

- Patient with profuse sputum or with central consolidation.

Frequency

- Positioning: Ventilated and critically ill patients: as required with the goal of once each hour or every other hour as tolerated, around the clock. Less acute patients should be turned every 2 (two) hours as tolerated.

Postural drainage along with percussion and vibration (PDPV)

- In critical care patients, involving those on mechanical ventilation, PDT should be performed every 4 to every 6 hours as indicated. PDT orders should be re-evaluated at least every 48 hours based on assessments from personal treatments.

- In voluntarily breathing patients, frequency should be determined by assessing patient response to therapy.

- Acute care patient orders should be re-evaluated based on patient response to therapy at least every 72 hours or with an exchange of patient status.

- Domiciliary patients should be re-evaluated every 3 (three) months and with a change of status.

Modern techniques

- Over the years, so many additional noninvasive clearance methods have been developed to augment this traditional approach. Modern techniques use a different flow through breath control to mobilize secretions.

- It involves an active cycle of breathing and autogenic drainage.

Active cycle of breathing technique

- Active cycle of breathing technique (ACBT) is an active breathing technique performed by the patient and can be used to mobilize and clear extra pulmonary secretions and generally improve lung function.

- It has a series of three main phases: Breathing control, Thoracic expansion, and Forced expiratory technique (FET).

Autogenic drainage

- Autogenic drainage is a diaphragmatic breathing pattern used by patients with respiratory illnesses (e.g., cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis) to clear the lungs of mucus and other secretion.

- Different techniques are used, all of which combine positive reinforcement of deep breathing and voluntary cough suppression for as long as possible previous evacuating the airways of mucus.

Instrumental techniques

Instrumental techniques such as non-invasive ventilation have been considered utilized as adjunct therapy to airway clearance and to provide respiratory support. Usual instrumental techniques are:

- Positive expiratory pressure (PEP): There are different positive expiratory pressure devices that provide resistance to expiration through a mouthpiece or facemask, followed by forced expirations. The inhalation is at tidal volume (TV), and the expiration is slightly active against devices. These devices assist to remove secretions by increasing functional residual capacity and thus enhancing collateral ventilation and removing secretions from collapsed airways. Certain of the devices are Flutter, Acapella, lung flute, etc.

- Continuous Positive Airway Pressure: created by exhalation against a constant opening pressure, this produces positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP). Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) can also be delivered by commercially available pressure drivers. These generally need tightly fitting nasal prongs or a Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) face mask. Bubble Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) can be used in a low-resource environment and in the pediatric population. It involves an interface (nasal cannula), inspiratory tubing, and expiratory tubing immersed in an underwater battle system.

- High-Frequency Chest Wall Oscillation (HFCWO): an airway clearance technique in which external chest wall oscillations are applied to the chest utilizing an inflatable vest that wraps around the chest. These machines produce vibrations at variable frequencies and intensities, helping to loosen thin mucus and separate it from airway walls.

- HFCWO includes an inflatable jacket that is attached to a pulse generator by hoses that mechanically enable the equipment to perform at variable frequencies (5–25 Hz). The generator conveys air through the hose, which causes the vest to inflate and deflate rapidly. The vibrations not only separate mucus from the airway walls but also assist move it up into the large airways. Commonly, it is paused during the 20- to 30-minute HFCWO treatment every 5 minutes to cough out loosened mucus that has moved into the large airways.

- Intrapulmonary Percussive Ventilation (IPV): designed to promote mobilization of bronchial secretions and involve efficiency and distribution of ventilation, providing intrathoracic percussion and vibration and an alternative system for the delivery of positive pressure to the lungs. Each Intrapulmonary Percussive Ventilation (IPV) session lasted fifteen minutes and was performed twice a day (morning and afternoon). Intrapulmonary percussive ventilation (IPV) uses a pneumatic device to deliver a series of pressurized gas minibursts at rates of 100 to 225 cycles per minute to the respiratory tract, by a mouthpiece. The duration of each and every percussive cycle is manually controlled by a thumb button. During the cycle, continuous PAP is maintained in the airway. It incorporates a nebulizer for the delivery of the aerosol.

Assessment of need and outcome

The following should be assessed together to establish a requirement for chest physiotherapy:

- Excessive sputum production.

- Effectiveness of cough.

- History of pulmonary problems resulted successfully with PDT (eg, bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, lung abscess).

- Reduced breath sounds or crackles or rhonchi suggest secretions in the airway.

- Change in vital signs.

- Unusual chest x-ray consistent with atelectasis, mucus plugging, or infiltrates.

- Deterioration in arterial blood gas (ABG) values or oxygen saturation.

The following can be used as a result tool to determine the effectiveness of treatment:

- Change in sputum production.

- Change in breath sounds of lung fields.

- Patient subjective response to therapy.

- Change in vital signs.

- Change in a chest x-ray.

- Change in arterial blood gas (ABG) values or oxygen saturation.

- Change in ventilator variables.

- Change in Modified borg scale- dyspnea level.

- Change in Peak Expiratory Flow Rate.

Contraindications of Conventional Techniques

Positioning

All positions are contraindicated for:

- Intracranial pressure (ICP) > 20 mm Hg,

- head and neck injury until stabilized (Absolute),

- Active hemorrhage with hemodynamic instability (Absolute),

- Recent spinal surgery (ex, laminectomy) or acute spinal injury,

- Acute spinal injury or active hemoptysis,

- Empyema,

- Bronchopleural fistula,

- Pulmonary edema associated with congestive heart failure,

- Large pleural effusions,

- Pulmonary embolism,

- Aged, confused, or anxious patients who do not allow position changes,

- Rib fracture, with or without flail chest,

- Surgical wound or healing tissue.

Trendelenburg position is contraindicated for

- Intracranial pressure (ICP) > 20 mm Hg,

- Patients in whom improved intracranial pressure is to be avoided (eg, neurosurgery, aneurysms, eye surgery),

- Uncontrolled hypertension,

- Distended abdomen,

- Oesophageal surgery,

- Latest gross hemoptysis related to current lung carcinoma treated surgically or with radiation therapy,

- Uncontrolled airway at threat for aspiration (tube feeding or recent meal),

- Back Trendelenburg is contraindicated in the presence of hypotension or vasoactive medication.

External Manipulation of the Thorax

In addition to the contraindications listed

- Subcutaneous emphysema,

- Recent epidural spinal infusion or spinal anesthesia,

- Current skin grafts, or flaps, on the thorax,

- Burns, open wounds, and skin contaminations of the thorax,

- Currently placed transvenous pacemaker or subcutaneous pacemaker (particularly if mechanical devices are to be used),

- Suspected pulmonary tuberculosis,

- Lung contusion,

- Bronchospasm,

- Osteomyelitis of the ribs,

- Osteoporosis,

- Coagulopathy,

- Complaint of chest-wall pain.

Complications

- Hypoxemia,

- Bronchospasm,

- Increased Intracranial Pressure,

- Acute Hypotension during Procedure,

- Pulmonary Hemorrhage,

- Pain or Injury to Muscles, Ribs, or Spine,

- Vomiting and Aspiration,

- Bronchospasm,

- Dysrhythmias.

How do you treat bronchospasm at home?

- There are no home remedies that can stop bronchospasm once it is started. You will need a short-acting bronchodilator (such as an inhaler) to ease the symptoms of your attack. If you have already been diagnosed with bronchospasm, you probably already have a bronchodilator.

- But if this is your first episode and you do not have a bronchodilator, you should go to the nearest emergency room for treatment.

- Some experts believe that breathing exercises can decrease your risk of bronchospasm. However, research is ongoing and more evidence is needed in this part. Even so, these exercises can not stop bronchospasm once it is started.

- If you are prone to bronchospasms, ask your healthcare provider (doctor) how to best manage them.

Can I prevent bronchospasm?

You can not prevent bronchospasm altogether, but there are things you can do to reduce your risk. For example:

- Stay hydrated to loosen up the mucus in your chest.

- Do not smoke or vape.

- Warm up the previous exercise.

- Limit exercise when the pollen count is increased, especially if you have allergies.

- Limit exercise in cold temperatures.

- Stay up to date on your vaccines, especially if you are 65 or over.

What can I expect if I have bronchospasm?

- If you have been diagnosed with bronchospasm, your healthcare provider will probably prescribe a short-acting bronchodilator to use in case of an attack. They may also give you a long-acting bronchodilator to assist reduce your risk of bronchospasms in the future.

How long does bronchospasm last?

- An episode of bronchospasm commonly lasts between seven and 14 days. Your healthcare provider (doctor) will give you medications to manage your symptoms during this time.

Is bronchospasm life-threatening?

- Left untreated, serious bronchospasm can be life-threatening. However, with prompt intervention, symptoms commonly subside within minutes. If you create bronchospasm symptoms, use your bronchodilator immediately.

When should I see my healthcare provider?

Call your doctor if you have symptoms of bronchospasm that limit your daily activities or do not clear up in a few days. If you develop bronchospasm symptoms that linger or interfere with your daily activities, contact your healthcare provider (doctor).

- Have trouble catching your breath?

- Are coughing up bloody mucus.

- Have chest pain while breathing.

- Feel dizzy or faint.

NOTE

- Bronchospasm is treatable, yet having an episode can be a scary experience. If you have asthma, COPD, or other respiratory conditions that make you more prone to bronchospasm, talk to your healthcare provider (doctor).

- They will prescribe medications that can reduce your risk and ease your symptoms should a bronchospasm occur.

FAQs

allergens, such as dust and pet dander. chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), is a group of lung diseases that includes chronic bronchitis and emphysema. chemical fumes. general anesthesia during surgery.

Exercise bronchospasm treatment

Use a regular inhaler before you exercise. Take a mast cell stabilizer. Use a long-acting inhaler. Take specialized, anti-inflammatory medication.

A bronchospasm occurs when the muscles that line the airways of the lungs constrict or tighten, reducing airflow by 15 percent or more. People with asthma, allergies, and lung conditions are more likely to develop bronchospasms than those without these conditions, as are young children and people over 65 years of age.

Bronchospasm occurs when the airways (bronchial tubes) start to spasm and contract. This makes it hard to breathe and causes wheezing (a high-pitched whistling sound). Bronchospasm can also cause frequent coughing without wheezing and feeling short of breath.

Beta-blockers including cardioselective beta-blockers, cholinergic agonists, inhaled agents, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE), vindesine, histamine liberators, etc…, can also induce bronchospasm.

Bronchospasm can be caused due to swelling or irritation of the airways. An episode of bronchospasm generally subsides within 7-14 days. A doctor generally prescribes medicines to clear the airways and prevent wheezing.

Lie on your back with your shoulders and neck elevated.

If your sinuses drain more during the night, sleeping with pillows under your shoulders gives the drainage a gravity boost so that you can keep breathing easy while you sleep.

Abstract: Introduction: Panic attacks causing acute bronchospasm is a life-threatening condition that can cause acute respiratory failure and rarely it can be severe enough to require intubation. Here we present a patient with anxiety-induced bronchospasm that lead to intubation to maintain adequate ventilation.

Terbutaline injection is used to prevent bronchospasm in patients 12 years of age and older with asthma, bronchitis, emphysema, and other lung diseases. Terbutaline belongs to the family of medicines known as bronchodilators.

One Comment