The Sacroiliac Joint Examination

The Sacroiliac Joint Examination is an important part to diagnose SI Joint Dysfunction where a Physical therapist performs various examination tests to rule out other related conditions.

Table of Contents

Background

- Test Item Cluster (TIC) is a group of special tests designed to improve diagnostic utility and make clinical decision-making easier.

Clinically, it’s important to be able to tell a diagnosis of SIJ pain from another one. Although it has been debated in the literature, it is generally agreed that sacroiliac joint pain is the cause of mechanical low back or buttock pain in 10-25% of patients who present. - Clinicians will be able to provide the right treatment to the right patients if they are able to accurately identify the sacroiliac joint as the source of the patient’s pain. This will improve speedy recovery of the the patient.

- Levangie et al. created a TIC that used the following tests to identify SIJ dysfunction: supine long sitting test, standing flexion test, sitting PSIS palpation test, and prone knee flexion test. By contrasting the outcomes of patients who were being treated for other physical impairments that were not related to the back with those of patients who complained of LBP, the researchers evaluated the diagnostic utility of those tests.

- The cluster of these tests had a sensitivity of 0.82, a specificity of 0.88, a + LR of 6.83, and a – LR of 0.20, as reported by them. However, it is important to note that the special tests used in this TIC are not very reliable.

- In a more recent study, Laslett et al. evaluated the McKenzie evaluation’s diagnostic value when used in conjunction with the following SIJ tests: Gaenslen, thigh thrust, distraction, sacral thrust, and compression The right and left side bending, flexion in lying, and extension in lying were the components of the McKenzie assessment.

- Sets of ten were used to perform the repeated movements, and the centralization and peripheralization of symptoms were recorded. Patients suffering from discogenic pain were identified by using the centralization phenomenon caused by repeated movement. Patients who experienced discogenic pain were ruled out following the McKenzie evaluation. The authors discovered that using a set of SIJ tests as part of a specific clinical reasoning process can make it easier to determine whether SIJ dysfunction is present.

- In relation to a diagnostic injection, Laslett et al. conducted additional research into the diagnostic efficacy of pain provocation sacroiliac joint (SIJ) tests on their own and in a variety of combinations. In this study, the following tests were used: Compression, sacral thrust, right-sided Gaenslen’s test, distraction, and right-sided thigh thrust Because of their acceptable inter-rater reliability, those tests were chosen.

- They discovered that provocation SIJ test composites had significant diagnostic value. The four chosen tests—distraction, compression, sacral thrust, and thigh thrust—have the highest predictive power. SIJ pathology can be ruled out if all six SIJ provocation tests do not reproduce symptoms.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

- The sacroiliac joints are situated on either side of the spine, connecting the sacrum to the pelvic bones. The pelvic girdle’s primary function is to distribute forces between the upper and lower limbs and to absorb shock for the spine. Shearing, torsion, rotation, tension, and other forces are applied to the SI joint.

- The SI joint has a significant impact on ambulation because it is the only orthopedic joint that connects our upper and lower bodies. The synovial joint is filled with synovial fluid and is relatively stiff. Hyaline cartilage covers the articular surfaces of the ilium and sacrum bones, and dense fibrous tissue connects the two bones. Most of the time, SI joints only move a few degrees.

- Clinical Presentation

It can be difficult to distinguish sacroiliac joint syndrome symptoms from those of other types of low back pain. It’s hard to diagnose sacroiliac joint syndrome because of this. - The most typical symptoms are:

- Most of the time, pain is only felt in the buttock area. Patients frequently describe feeling a sharp, stabbing, or shooting pain that goes down the posterior thigh, usually not past the knee.

- The misidentification of pain as radicular pain is common.

- Pain-related difficulty sitting still for too long.

- Tenderness in the area of the sacroiliac joint’s posterior aspect (near the PSIS).

- When the joint is put under mechanical stress, like when you bend forward, it hurts.

- Nerve root tension and neurological deficits are absent.

- The pattern of erroneous sacroiliac movement.

- When they sit down, lie on their side of the pain, or climb stairs, patients frequently express pain.

Investigation

- X-rays for investigation: In order to find out what’s causing your pain, your doctor may order an x-ray of your pelvis, hips, or lumbar spine (low back).

- CT images: These can provide your doctor with an in-depth look at your bones and joints.

- MRI images: These can show if there is inflammation in your SI joints and give your doctor a close look at your soft tissues (like muscles and ligaments).

- Bone X-rays: If there is a possibility of bone abnormalities, your doctor may also order a bone scan. Bone scans can show if your bones are prone to inflammation in particular areas.

Palpation of the sacroiliac joint

- Palpation of the sacroiliac joint is one of the simplest ways to evaluate the SI joint. However, in recent years, the validity and reliability of palpating the SI joint have been questioned. Poor inter-tester reliability for static SI joint palpation has been shown in a number of studies, one of which is a nice one by Holgren and Waling.

- An intriguing article by McGrath, titled “Palpation of the sacroiliac joint: a sensory and anatomical challenge” where the idea of SI joint palpation was examined. It’s a fascinating and thought-provoking piece of writing. The difficulty of palpating something so deep, as well as the numerous layers of tissue that lie between the skin and the posterior SI joint, which is 5-7 centimeters deep into the skin, are discussed in the paper.

Physiotherapy assessment (Special Tests)

Sacroiliac Distraction Test

- The Sacroiliac Distraction Test—also known as the Gapping Test—is one of the special tests that is used in the Laslett SIJ Cluster testing. When it is used, the SIJ Distraction Test—also known as the Gapping Test—is used to add evidence—positive or negative—to the hypotheses that an SIJ sprain or dysfunction has occurred. The anterior sacroiliac ligaments are tested. The Sacroiliac Joint Stress Test and the Transverse Anterior Stress Test are other names for this test.

- Technique

The examiner applies a force to both the anterior superior iliac spines (ASIS) that is vertically oriented and directed posteriorly to the patient, who is lying supine. - Note: In an effort to replicate the patient’s symptoms, Cook and Hegedus (2013) recommend applying a sustained force for 30 seconds before applying a vigorous force repeatedly. However, neither timings nor adjustments to force are suggested by Laslett (2008).

- It is quite possible that different therapists will practice this test in a variety of ways due to the lack of standardization in the method. This will result in response variability and lower inter-tester reliability. There is no evidence to suggest that either approach is superior, so additional evidence is required.

- The likely outcome is a DISTRACTION of the sacroiliac joint’s anterior aspect.

If a test matches the patient’s symptoms, it is positive. This suggests either dysfunction in the SIJ or an anterior sacroiliac ligament sprain. - However, to ensure maximum reliability and validity when confirming hypotheses, this test should be used in conjunction with an SIJ testing cluster. For more information, see the Laslett SIJ testing cluster.

Sacroiliac Compression Test

- Purpose

- The Sacroiliac Joint (SIJ) Compression Test, also known as the “Approximation Test,” is a pain provocation test that tries to replicate a patient’s symptoms by putting stress on the SIJ structures, particularly the posterior SIJ ligament.

- Technique

- The patient lies on their side, and the examiner presses toward the floor with their hands over the upper part of the iliac crest. The movement puts pressure on the sacrum as it moves forward. A possible sacroiliac lesion and/or a sprain of the posterior sacroiliac ligaments is indicated by an increased sensation of pressure in the sacroiliac joints. Pain or the recurrence of the patient’s symptoms are indicators of a positive result.

- Negative Test

- Pain or the recurrence of the patient’s symptoms are indicators of a positive result.

Posterior Pelvic Pain Provocation Test

- Purpose

The posterior pelvic pain provocation test is a pain provocation test that is used to determine the presence of sacroiliac dysfunction. There is no pain or pain other than the patient’s reproduction of pain. It is frequently utilized during pregnancy to differentiate between low back pain and pain in the pelvic girdle. - The examination is also called:

- Technique

With the patient supine, the hip is flexed to 90° (with the bended knee) for the PPPP test, P4 test, Thigh thrust test, and POSH test to stretch the posterior structures. The femur serves as a lever to move the ilium forward by applying axial pressure along its length. To secure the position of the sacrum, one hand is placed beneath it, and the other hand is used to force the femur downward. Laslett and Williams advise against excessive hip adduction due to the patient’s discomfort, while Broadhurst and Bond recommend adding hip adduction toward the midline. - If the axial pressure causes pain over the patient’s familiar sacroiliac joint, the test is positive for pelvic girdle pain.

Sacral Thrust Test

- Purpose

- The purpose of the sacral thrust test is to diagnose sacroiliac dysfunction using a pain provocation test. While a single positive test does not have high diagnostic accuracy, other sacroiliac pain provocation tests in combination provide reliable evidence for sacroiliac dysfunction.

- The examination is also called:

- Sacral compression test

- Downwards pressure test

- Sacral spring test

- Technique

- The examiner applies an anteriorly directed pressure over the sacrum while the patient is lying down for the sacral compression test and the downward pressure test. The other hand is supporting the hand that is directly on the sacrum. Due to the fact that the examination bench holds the ilia in place, the goal is to apply an anterior shear force to both sacroiliac joints. If pain is felt again in the sacroiliac area, the test is positive.

Gaenslen Test

- Purpose

One of the five provocation tests that can be used to identify musculoskeletal abnormalities and primary-chronic inflammation of the lumbar vertebrae and the Sacroiliac joint (SIJ) is the Gaenslen Test (Gaenslen’s maneuver). The following tests are included: the Sacral Thrust Test, Compression Test, Distraction Test, and Thigh Thrust Test. - A useful tool for identifying patients who are more likely to have SIJ pain than any other painful condition is the clinical prediction rule of three or more positive provocation tests that provoke familiar back pain and non-centralization of pain. When interpretation is restricted to back pain patients whose symptoms cannot be made to “centralize” with repeated movement testing, the diagnostic accuracy of composites of SIJ tests increases. Positive SIJ tests in patients with discogenic pain should be ignored because centralization is extremely specific to that condition.

- Specifically, an SIJ lesion, pubic symphysis instability, hip pathology, or L4 nerve root lesion can all be detected by Gaenslen’s test. It can also put a strain on the femoral nerve. In SIJ, this test is frequently utilized for the detection of spondyloarthritis, sciatica, and other forms of rheumatism.

- Technique

The patient lies down with the painful leg resting on the edge of the treatment table at the beginning. The examiner flexes the non-symptomatic hip sagittally while also flexing the knee (up to 90 degrees). While the therapist stabilizes the pelvis and applies passive pressure to the leg being tested (symptomatic) to hold it in a hyperextended position, the patient should hold the non-tested (asymptomatic) leg with both arms. A flexion-based counterforce is applied to the flexed leg, pushing it in the cephalad direction and causing torque to the pelvis, while a downward force is applied to the lower leg (symptomatic side), putting it into hyperextension at the hip. - The test is deemed positive for an SIJ lesion, hip pathology, pubic synthesis instability, or L4 nerve root lesion if the patient’s normal pain is reproduced. In the meantime, this test may put stress on the femoral nerve as well.

- If the patient complains of pain on both sides, it is best to test both sides. Importantly, a diagnosis of SIJ pathology is only possible with at least three positive SIJ provocation tests.

Sacroiliac Gapping Test

- Exam type: Passive stress test

- Patient and Body Segment Positioning:

The patient is lying on their back. - Position as an Examiner:

The examiner is standing with his or her head pointing at the feet. - Tissues Under Examination:

Testing the anterior SI joints, specifically the sacroiliac joints - Performing the Test:

The examiner presses down and out while crossing their hands and placing them on the ASIS. - Test Results:

If pain in one side of the sacroiliac joint or in the posterior leg is felt, the test is positive. - Interpretation:

When a test comes back positive, it means that the anterior SI ligaments have been strained.

Misplaced actors’ hands, which could lead to misinterpretation:

Misinterpretation can occur if the patient has previously experienced hamstring pain.

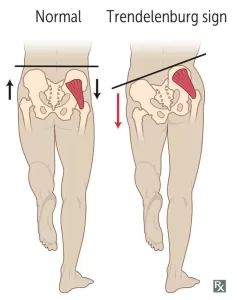

Trendelenburg Sign

- Description of the Trendelenburg Sign The Trendelenburg sign is a brief physical examination that can help the therapist determine whether or not there is hip dysfunction. The Brodie–Trendelenburg test, which is used to determine the competence of the valves in the superficial and deep veins of patients with varicose veins, should not be confused with this, which is referred to as the Trendelenburg test.

- Typically, weakness in the hip abductor muscles is indicated by a positive Trendelenburg sign: both the gluteus medius and the gluteus minimus These findings may be linked to a variety of hip abnormalities, including rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, and congenital hip dislocation.

- During a one-leg stand on the affected side, if the pelvis drops to the opposite side, the test is positive. Additionally, this can be observed during gait: During the stance phase on the affected extremity, compensation is achieved by side flexing the trunk in the direction of the involved side.

- Purpose

The Trendelenburg Test’s objective is to identify hip abductors’ weakness.

The Trendelenburg sign can be used to look for weakness in the hip abductors of the standing leg as well as other mechanical, neurological, or spinal conditions like congenital hip subluxation or dislocation. - Technique

A patient is asked to stand on one leg for thirty seconds without leaning to one side. If they have trouble keeping their balance, they can hold onto something. During the single-leg stance, the therapist watches the patient to see if the pelvis stays level. If during unilateral weight bearing the pelvis drops toward the unsupported side, a positive Trendelenburg Test is indicated.

Leg Length Discrepancy

- Definition

- Leg length discrepancy, also known as anisomelia, is a condition in which the lengths of the paired lower limbs are significantly different from one another.

- Leg length discrepancy (LLD) has long been a contentious issue among clinicians and researchers. The extent of LLD that is considered to be clinically significant, the prevalence, reliability, and validity of the measuring methods, the effect of LLD on function, and its role in various neuromusculoskeletal conditions are just a few of its many aspects, though its presence is acknowledged.

- Classification of Leg Length Disparity (LDD) There are two categories of LDD.

- Anatomical

- Inequality in limb length due to the anatomical structure. It is a physical (osseous) shortening of one lower limb that occurs between the ankle mortise and the trochanter femoral major. While acquired conditions include trauma, fractures, orthopedic degenerative diseases, and surgical disorders like joint replacement, congenital conditions include mild developmental abnormalities that are present at birth or in childhood. Based on radiographic measurements, a systemic review found that 90% of the normal population had some variation in bony leg length, with 20% having a difference of more than 9 millimeters.

- Functional

- Shortening that is functional and not structural. It is a unilateral asymmetry of the lower extremity that does not result in any shortening of the lower limb’s osseous components. Lower limb mechanics changes like joint contracture, static or dynamic mechanical axis malalignment, muscle weakness, or shortening can cause FLLD. A non-functional evaluation, such as radiography, cannot reveal these flawed mechanics. An abnormal motion of the hip, knee, ankle or foot in any of the three planes of motion can lead to FLLD.

- It is evident that studies using people who have had true LLD for a long time are better able to deal with larger LLD than studies using people who have LLD that is induced or artificial. This is reasonable because most people would be able to reduce the energy and mechanical costs of LLD with enough time.

- Additionally, younger people are generally better able to adapt to larger LLD than older people (which makes sense given that older people have greater difficulty mastering novel motor tasks and that gait patterns differ significantly between young and old people). It also appears that the person’s level of activity is a factor.

- It appears that people who participate in sports or spend the majority of their day on their feet are more susceptible to LLD than those who are less active.

FAQ

The Gillet test, which is also known as the march or stork test, the standing flexion test, the sitting flexion test (also known as Piedallu’s sign), and the supine-to-sit test are some of the more common diagnostic procedures.

These tests can aid in the diagnosis of SI joint disease or dysfunction by a clinician like a physical therapist, pelvic health specialist, or pain management specialist.

Palpation might be the most accurate way to tell if SIJ pain is present. Most of the time, the patient presses their thumb directly onto a specific spot in the PSIS (sacral sulcus) dimple. Typically, the patient can precisely replicate the pain in that one location (Fortin’s finger sign).

Because lying on your back relieves pressure on the SI joint, it can be helpful. Additionally, putting a pillow under your legs can help alleviate some pressure on the SI joint. Sleep on a mattress that is both supportive and not too soft or hard.

Psoas syndrome is a very uncommon condition caused by injury to the psoas muscle, a long muscle in the back. Back pain is caused by this condition. Psoas syndrome can happen to anyone, but athletes are more likely to get it. Most of the time, physical therapy is used to treat it.