Radial Head Dislocation

Table of Contents

What is a Radial Head Dislocation?

Radial head dislocation is a medical condition characterized by the displacement of the radius bone at the elbow joint. The radius is one of the two bones in the forearm, and it plays a crucial role in the movement and stability of the arm. When the radial head becomes dislocated, it shifts out of its normal position, causing pain, limited range of motion, and functional impairment.

This condition is commonly seen in children, particularly between the ages of 2 and 6 years, and is often referred to as “nursemaid’s elbow” or “pulled elbow.” It can also occur in adults due to traumatic injuries or repetitive stress on the elbow joint.

Rarely, does a radial head dislocation occur alone. It typically manifests in youngsters as a nursemaid’s elbow, a partial dislocation, or subluxation. Although uncommon, complete radial head dislocation is most frequently linked to high-force arm injuries, which frequently involve a forearm fracture or dislocation. A comprehensive history, physical examination, and imaging can help with the right assessment and reduce the likelihood of problems from a missed diagnosis. A missing or untreated radial head dislocation will require surgical correction because of its relationship with ulnar fractures and other problems, even if the reduction method is often a simple operation for radial head subluxation.

When the radial head is moved from its natural articulation with the ulna and the humerus, radial head dislocation happens.

Either congenital or acquired dislocations are possible. A “pulled elbow,” which is a radial head subluxation and diminishes spontaneously or quickly with supination, should be recognized as a radial head dislocation.

For infants under the age of six, isolated radial head subluxation, often known as “nursemaid’s elbow” or “pulled elbow,” is the most frequent upper extremity injury, peaking around two to three years old [1–3]. Axial traction applied to the forearm (pulling) accounts for around half to two-thirds of instances, causing the annular ligament to slide and become stuck between the radial head and capitellum. Adults seldom experience radial head subluxations or dislocations without a fracture or elbow dislocation nearby

Anatomy:

The radius and ulna are the two bones located in the forearm. At the elbow, both of these bones connect to the humerus, the upper arm bone. These three bones work together to produce the elbow joint. The annular ligament, which joins the radius to the remainder of the elbow joint, is a flexible, fibrous band of tissue that surrounds the top, or head, of the radius.

When a portion of the annular ligament slides across the radial bone’s head and becomes entrapped in the radiohumeral joint, it results in radial head subluxations. The annular ligament’s displacement is what causes the symptoms related to radial head subluxation.

A partial dislocation, or subluxation, occurs when the bone still makes some contact with the ligament. The radius bone has been completely pushed out of place when there is a full dislocation.

What is a radial head subluxation or dislocation?

An injury to the elbow joint is called a radial head subluxation. The top of the radius, one of the two main bones present in the forearm, is referred to as the radial head, and the term “subluxation” denotes partial dislocation. Injuries that cause the top of the radial bone to partially dislocate from the remainder of the elbow are called subluxations of the radial head.

A sudden strain on the forearm may result in the condition, which is also known as a pulled elbow, babysitter’s elbow, nursemaid’s elbow, RHS, or annular ligament displacement, and is a frequent injury in kids, especially in those who are between the ages of one and four. This is due to the annular ligament’s considerably increased vulnerability in young children, which increases the likelihood that it may slip over the radial head in the event of a rapid pulling force. This ligament maintains the radial bone in place at the elbow. ref19

People who have pulled their elbow prefer to hold the injured arm close to their body, frequently supporting it with the other hand or their stomach, and they are reluctant to utilize the arm. They could say their arm hurts. The majority of the time, a doctor may simply put the joint back into position to correct a subluxation of the radial head; problems are rare.

Full dislocations of the radial head are extremely uncommon in both adults and children. If they do develop, they are usually brought on by a congenital disorder or a high-force trauma. Similar to a pulled elbow, but more severe, symptoms might be present. Along with other arm injuries, including a forearm fracture, full radial head dislocations commonly happen. Therefore, the focus of treatment is on all related ailments, which may require surgery.

Other terms for radial head subluxation

- Pulled elbow

- Babysitter’s elbow

- Nursemaid’s elbow

- Partial dislocation of the radial head

- Annular ligament displacement

- RHS

- Pronatio dolorosa

Causes of radial head dislocation:

The radial head is held steady by the annular ligament. An axial force on an extended, pronated forearm in infants with subluxation causes the annular ligament to slide across the radial head. On the other hand, both toddlers and adults can have a full radial head dislocation. The annular ligament is typically torn in such injuries from high-force trauma. Less frequently, the radial head will slide beneath the annular ligament since it is still intact and attached to the lateral collateral ligament and the ulna

Pathophysiology:

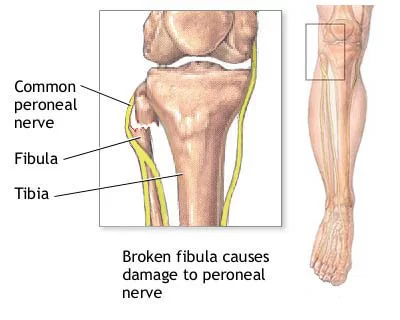

The proximal and distal radioulnar joints, as they are appropriately titled, connect the radius and ulna at both ends. It is challenging to disturb one side of a ring without simultaneously affecting the other, much like the mandible and pelvis. As a result, it’s critical to confirm that a radial head dislocation—also known as the Monteggia fracture-dislocation—is actually separated from an ulna fracture.

Pediatric patients frequently have plastic deformations of the bones. The ulna may therefore develop a bowing fracture rather than a transverse ulna fracture as a result of radial head dislocation; the ulnar bow sign is useful to evaluate this. Although unusual in youngsters, Monteggia fracture-dislocation is by no means unheard of.

People with neuromuscular diseases and contractures, such as cerebral palsy and brachial plexus injuries, are also susceptible to radial head dislocation.

A complete radial head dislocation happens as a result of a high-force injury, such as a serious car accident or a fall onto an extended arm. The radial head seldom dislocates by itself without causing further damage. A radial head dislocation can result in the following injuries:

- Monteggia is broken.

- Dislocated elbows

- A fractured elbow

- The terrible trinity of elbow injuries (radial head fracture, ulnar coronoid process fracture, and elbow dislocation)

Congenital dislocation of the head of the radial bone may be present together with other congenital anomalies, such as:

- Ehlers-Danlos disease

- Syndrome of the nail-patella

- Ultnar dysplasia

- Radioulnar synostosis

- Dyschondroplasia

Types of radial head subluxation and dislocation

These are some examples of radial head subluxations and dislocations:

RHS pulled elbow, babysitter’s elbow, nursemaid’s elbow, radial head subluxation, and annular ligament displacement

A partial dislocation of the radial head is the same injury that is referred to by each of these names. Children between the ages of one and four are most commonly affected by this elbow injury, which is the most prevalent type of dislocation that can affect the head of the radius bone in the forearm. Over 80% of pulled elbow instances in toddlers occur between the ages of one and three.

Full radial head dislocation

A complete radial head dislocation is far less common in children than a radial head subluxation. Full dislocations do occasionally happen in youngsters, although they still happen more frequently in adults than subluxations.

Dislocation of the radial head is frequently observed in victims of high-force trauma, such as severe falls or vehicle accidents. It frequently occurs in conjunction with another injury, such as a fracture of the ulna, the other forearm bone.

A congenital defect that exists at birth may potentially cause the illness. Complete dislocation of the radial head that happens by itself is quite uncommon.

Full dislocations frequently cause apparent elbow swelling, although radial head subluxations do not. This is a key symptom differential between the two conditions.

Injured radial head dislocations

It is highly uncommon for the radial head to dislocate without any additional accompanying injuries, even when induced by a wound. The most frequent complication is a fracture of the ulna, the other forearm bone. A radial head dislocation may cause the following injuries:

- Fractures of the ulna, such as the Monteggia fracture

- Other dislocations of the elbow, include anterior, posterior, and divergent dislocations

- Fractures of the humeral condyle, which occur at the elbow

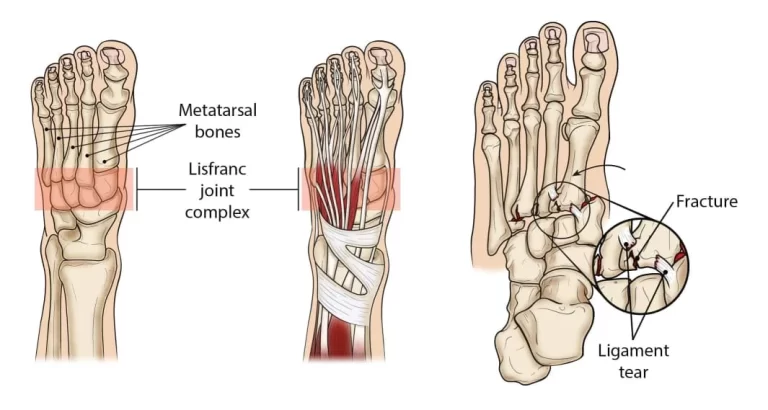

- Injuries to the forearm that are complex, such as the Essex-Lopresti injury. This injury includes a rupture of the interosseous membrane, a ligament-like sheet of tissue that stabilizes the bones in the forearm, a fracture of the radial head, and disruption of the distal radioulnar joint, which joins the two forearm bones.

- The most prevalent cause of dislocation of the radial head in adults is a high-force trauma or injury, like a vehicle accident. Other elbow or forearm injuries are frequently present in addition to the dislocation.

A congenital disease that causes radial head dislocations

A congenital dislocation of the radial head may occur in certain newborns. Despite being the most typical congenital elbow deformity, this is uncommon. When it happens, it is typically present together with other inherited syndromes or disorders, such as:

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome is a set of illnesses that all have an impact on the body’s connective tissues and can cause hypermobility in the joints.

- A hereditary condition called Nail-Patella Syndrome can cause skeletal deformities

- Low bone density is a frequent complication of Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome.

- An improper joining of the radius and ulna bones in the forearm is called radioulnar synostosis.

- Male neonates with Klinefelter syndrome, a chromosomal disorder in which an extra X chromosome is present at birth, may have thinner and more delicate bones.

- The elbows may be impacted by the bone development condition achondroplasia, which results in dwarfism.

- Omodysplasia is an uncommon skeletal condition that shortens the limbs.

- Hereditary multiple exostoses can lead to abnormalities when masses of bone accumulate on long bones in the lower and upper limbs

- Due to the bone development condition mesomelic dysplasia, the legs and forearms frequently have undeveloped bones.

- Bones with osteogenesis imperfecta, a genetic disorder that causes them to be brittle and readily breakable,

- Infants with congenital radial head dislocations are frequently asymptomatic, meaning they may not exhibit any outward symptoms or indicators of the dislocation right away. As a result, when a person begins utilizing the afflicted limb more often later in life, a diagnosis of radial head dislocation may be made.

Radial head subluxation signs and symptoms

Because pulled elbows and subluxation of the radial head most commonly affect toddlers and young children, it’s crucial to watch out for any of the following signs that might indicate this injury:

- Holding the hurt arm in close proximity to the body

- Keeping the damaged arm in a little bend—typically between 15-20 degrees—while you’re holding it

- Using the other hand to support the damaged arm’s weight

- Reluctance to utilize the arm

- Refusal to completely extend or flex the arm

- Pain in the wrist, arm, or elbow that is frequently poorly localized and is dull, vague, or aching

- Even though a pulled elbow usually hurts, especially initially, pain is not necessarily the main indicator that an injury has happened. In some situations, a youngster may carry on acting normally except for their resistance to using the injured arm.

Notably, a pulled elbow rarely results in bruising, oedema, or other types of cosmetic damage to the afflicted region.

Full radial head dislocations typically cause symptoms that are comparable to pulled elbows but a little more severe. For instance, the affected individual could continue to have the damaged arm bent, but at a sharper 90-degree angle. Additionally, they could feel greater discomfort and be less willing to move their arm.

Full dislocations frequently cause apparent elbow swelling, although radial head subluxations do not. This is a key symptom differential between the two conditions.

Risk factors for radial head subluxation

Because the annular ligament that maintains the elbow bones in place is thinner in children than in adults, the radial bone can sublux relatively quickly in young children. The most frequent cause of this injury is a rapid yank on the child’s arm, which causes the bone to explode out of its normal position.

There are several potential risk factors for a pulled elbow or radial head subluxation.

- Advancing while pulling a youngster by the arm

- Retaining a child’s arm as they withdraw

- Holding a child’s arm or catching them as they fall

- Using one’s arms to lift or swing a youngster

- Arm of a youngster being inserted through a sleeve

It’s good to know that falls are less likely to cause pulled elbows than they are to cause breaks or fractures.

The elbow’s annular ligament typically becomes strong and tight enough by the time a child is five years old to prevent radial head subluxations from occurring frequently.

Typically, either an accident or a congenital disease that exists from birth causes whole radial head dislocations.

Diagnosis of radial head subluxation or dislocation

A doctor’s clinical examination is the main basis for the diagnosis of radial head subluxation or dislocation. Typically, this assessment includes:

- Examining the afflicted arm physically

- Discussion of the signs and symptoms

- Review of medical background

A doctor must rule out a variety of different illnesses that might exhibit comparable symptoms before determining whether a partial or complete dislocation of the radial head is the cause of the symptoms. These circumstances include:

Broken radial head

- Other fractures, such as those to the ulna, clavicle, wrist, hand, and other parts of the elbow, might impair movement in the upper limbs.

- Hand soft tissue injuries

- Other illnesses, such as arthritis or bone infections such as osteomyelitis, might limit the range of motion of the arm.

Neurological causes

An X-ray is typically not necessary if the patient exhibits the typical clinical symptoms of subluxation or pulled elbow. This is due to the fact that a subluxation is just a partial dislocation and does not frequently manifest on an X-ray. However, a radiograph could be taken if:

- Suspected is a complete radial head dislocation.

- Suspected injuries include a fracture and other related ones.

- Unusual or unclear symptoms

- Initial efforts to realign the subluxated joint fail.

- To thoroughly evaluate the damage and prevent misinterpretation, an ultrasound examination could also be performed in specific circumstances. When diagnosing young children who might not be able to properly express their problems, ultrasounds can be a helpful diagnostic tool.

MRI scans can also be utilized to verify the diagnosis and evaluate ligament damage in the area. The only people to whom this is often recommended are those who have sustained recurrent elbow dislocations and may thus have considerable tissue damage.

Plain radiograph

The radial head is displaced anteriorly in practically all single traumatic dislocation instances. The radiocapitellar line, which should always cross the capitellum when drawn along the radial neck, is misaligned in lateral projection, making it the easiest to notice. Radial head dislocation has happened where this is lost. The ulna is likely to be bent if it is still intact.

To make sure that no further fractures, such as lateral condylar or epicondylar fractures, have occurred, it is crucial to evaluate the elbow ossification centres in young children. The ossification centers can be recalled using the acronym CRITOE.

When the pronator teres muscle shortens in individuals with contracture-related dislocation (such as cerebral palsy), the forearm pronates and the radial head dislocates posterolaterally.

Dislocations caused by brachial plexus palsy can occur anteriorly or posterolaterally, depending on which muscles are involved.

Treatment for radial head subluxation or dislocation:

The precise course of treatment for radial head subluxation or dislocation might vary depending on a variety of variables, including:

- Whether the damage is a complete dislocation or a subluxation

- Whether there are any other injuries, such as fractures, that may be present

- Whether a youngster or an adult is impacted

- Whether the illness is due to a congenital defect or a traumatic injury

Non-operative therapy

For patients who do not also have comorbid injuries, the first course of therapy is often an attempt to physically manoeuvre the radial head back into the joint (closed reduction). Doctors can frequently execute closed reductions swiftly and efficiently, especially in situations with pulled elbows.

It might not even be required to offer sedatives or painkillers before attempting to shift the bone back into position if a pulled elbow in a baby or kid is suspected. However, if the patient is an adult or the damage is a complete dislocation, painkillers may be provided throughout the closed reduction procedure.

The radial head may click softly when it returns to its proper place. After being reset, it is typical for the injured person to restore normal arm function and mobility within 30 minutes. Usually, no more treatment is needed once the function has returned. In order to support or immobilize the arm during healing, a sling or cast may be recommended.

After a few days, if a closed reduction doesn’t work, the patient’s discomfort persists, or they are still unable to fully use their arm, more testing, such as X-rays, may be necessary. If that is unsuccessful, surgery might be necessary.

Surgical treatment

For patients who have further injuries or for whom closed reduction procedures have failed, an open reduction—a surgical procedure to realign the radial head—may be advised. Due to their less flexible joints and potential for difficulty in restoring them as easily as those in children, adults are more likely than children to be indicated for surgical therapy.

If there are other injuries present, the accompanying injury may be the focus of the surgery rather than the radial head itself. For instance, when the ulna, or forearm bone, is broken and fixed, the radial head often returns to its original position on its own. The ulna may be secured in place using plates and screws to maintain the bone’s natural length and position after a fracture. By doing this, the likelihood of radial head dislocation recurring in the future is decreased.

Medical practitioners may overlook or misdiagnose radial head subluxations and dislocations because they are complicated injuries that might exhibit symptoms that are similar to those of other injuries, which could result in a chronic illness. The radial head might acquire abnormalities if the condition is untreated for more than three years. This is why radial head subluxations or dislocations that weren’t previously recognized are frequently handled surgically.

Initial therapy for radial head dislocation brought on by a congenital defect is frequently non-surgical. If surgery is necessary, it is frequently performed as an adult to address discomfort, mobility restrictions, or aesthetic issues.

Prevention of radial head subluxation and dislocation

By giving caregivers of young children a greater awareness of how the injury happens and what situations are most likely to cause it, such as swinging a kid by the arms or yanking a child hard by the arm, pulled elbow injuries may frequently be avoided.

The majority of full radial head dislocations are caused by high-force trauma, such as vehicle accidents or substantial falls. As a result, avoiding high-risk situations like contact sports or racing may help avoid injuries.

Prognosis:

When a nursing maid’s elbow is successfully reduced in a kid, there are seldom any long-term effects, and the child is unlikely to have a similar condition beyond the age of five when the annular ligament becomes stronger.

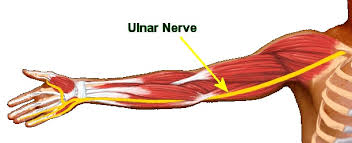

The radial head is close to the posterior interosseous nerve. It is the nerve that is most frequently injured when the radial head dislocates. Most frequently, its motor function is impacted.

Adult dislocations frequently require surgical correction; quick surgical treatment may result in arthritis and decreased range of motion, but delayed diagnosis and correction are more likely to result in a higher level of morbidity. The radial head deformity can develop if undetected or untreated for a number of years, requiring a more involved repair procedure.

FAQs:

But in adulthood, open surgery is almost always required for repair. While there are a number of surgical options available to treat chronic radial head dislocation, open reduction with plate and screw fixation or intramedullary ulna nailing, and annular ligament repair are the two that are most frequently employed.

After dislocating their shoulders, the majority of patients do not require surgery. If the incident that caused your shoulder to dislocate also damaged other parts of your body, surgery could be necessary. A closed reduction is either impossible or ineffective.

To give the muscles and other soft tissues time to rest and recover, doctors advise immobilizing the injured arm and shoulder for four to six weeks using a sling or brace. Applying an ice pack to the shoulder three times a day for 15 to 20 minutes will help to minimize discomfort and oedema during the first two days.

It could also be influenced by how severe your dislocation is. RICE (rest, ice, compression, and elevation) is the first line of therapy for any dislocation, according to Johns Hopkins University. After this therapy, the displaced joint may occasionally return to its original position on its own.

Dislocation-related discomfort is managed with NSAIDs, analgesics, and anxiolytics.