Pelvic Floor Muscles

Table of Contents

Overview

Your pelvic floor comprises muscles and connective tissues that support vital pelvic organs such as your bladder, gut (large intestine), and internal reproductive organs. Your pelvic floor muscles keep these organs in place while allowing you to move around and perform biological functions like peeing, pooping, and sex.

Your pelvic floor muscles, along with other essential muscle groups in your torso, or core, allow your body to absorb outside pressure (from lifting, coughing, etc.) in a way that preserves your spine and organs. These muscles also assist you in controlling your bowel and bladder function (continence).

Anatomy

Location

Your pelvic floor muscles are the foundation of your core muscles. The pelvic floor muscles, abdominal muscles, back muscles, and diaphragm (the muscle that controls breathing) are all part of your core muscles. These muscles join your pelvis and spine, producing stability in the middle of your body.

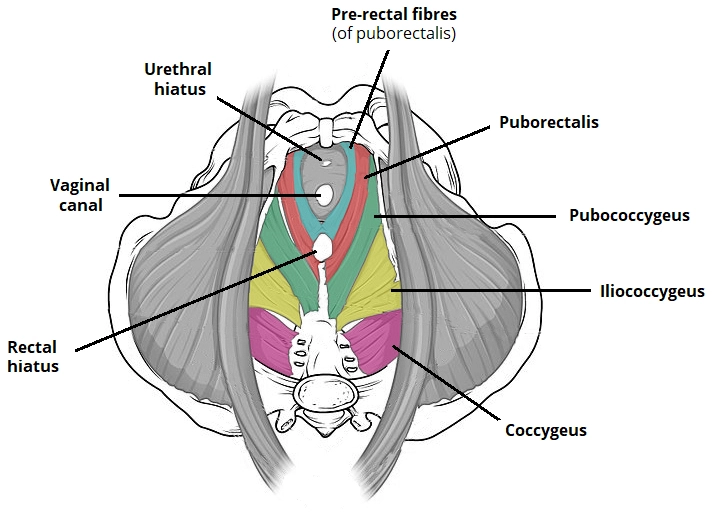

The pelvic floor muscles run from the pubic bone in the front to the tailbone (coccyx) in the rear. Both sitting bones (ischial tuberosity) on the right and left sides of your pelvis have muscles that expand outward. Several pelvic floor muscles join together to produce a single-layered muscle sheet with holes (anus, urethra, vagina).

Squeezing these three openings will help you locate your pelvic floor muscles.

Vaginal Opening: Insert one or two fingers into your vagina and try to squeeze them.

Urethra: Pretend you’re peeing and squeeze as if you’re halting the flow in the middle.

Anus: Squeeze your anus as if you were trying to keep yourself from breaking wind.

In each scenario, you should feel your pelvic muscles pull inward and upward. These are the pelvic floor muscles.

Structure

The pelvic floor is structured like a funnel. It connects to the walls of the smaller pelvis, dividing the pelvic cavity from the inferior perineum (area containing the genitalia and anus).

There are a few spaces in the pelvic floor that allow for urination and feces. There are two significant ‘holes’:

Urogenital hiatus – an anteriorly located gap that facilitates passage of the urethra (and, in females, the vagina).

Rectal hiatus – a centrally located gap that permits the anal canal to pass.

The perineal body is a fibrous node that connects the pelvic floor to the perineum and is positioned between the urogenital hiatus and the anal canal.

Functions

The pelvic floor muscles are largely supporting tissues. They aid in the retention of the pelvic viscera and prevent them from being forced through the pelvis during strain. It does this role by contracting automatically at rest and consciously during moments of increased intra-abdominal pressure (vomiting, sneezing, coughing, lifting a heavy object, or forced expiration).

Contraction of the levator ani muscles also obstructs the exit segments of the pelvic viscera. In other words, the muscles help to preserve urinary and fecal continence until it is time to urinate. This function is best demonstrated by the puborectalis muscle. Remember that it is a U-shaped muscular sling that arches around the anorectal junction. When this muscle contracts, it drags the anorectal junction anteriorly, generating a 90-degree angle between the rectum and anus. As a result, fecal matter cannot freely exit the rectum. The levator ani muscles must be relaxed for micturition (urination) and feces to occur.

The pelvic floor muscles also support the presenting fetal part – the part closest to the uterine outlet – during Childbirth. It stabilizes the fetus while the uterine cervix dilates and contracts. It also keeps the presenting part of the fetus in the anteroposterior plane of the pelvic outlet, which aids in the delivery procedure.

The bulk of the pelvic floor muscles are slow-twitch or type I muscle fibers, according to histology. Given the function of the pelvic floor muscles described above, the preponderance of type I fibers is significant. Remember that type I fibers are best for prolonged contractions, whilst type II fibers are required for rapid response to physiological changes.

Muscles

The pelvic floor muscles are known jointly as the levator ani and coccygeus muscles. They produce a huge skeletal muscle sheet that is thicker in certain places than others. The muscles are linked to a condensed region of the obturator fascia known as the tendinous arch of the levator ani muscle, which runs along the inner walls of the true pelvis. They are classified depending on their attachment locations and the pelvic organs with which they are linked. The levator ani is made up of three muscles: the puborectalis, the pubococcygeus, and the iliococcygeus. The levator ani does not include the coccygeus (also known as ischiococcygeus).

The accompanying fascia separates the levator ani’s pelvic surface from the visceral organs. The perineum serves as the medial and superior walls of the ischioanal fossa and its accompanying anterior recess. There is loose connective tissue between the muscle’s posterior border and the coccyx. Finally, the medial boundary of the two muscles is separated by the visceral organs’ outputs.

Levator Ani Muscles

The levator ani is a wide muscle sheet. Three paired muscles are the pubococcygeus, puborectalis, and iliococcygeus.

Puborectalis

The puborectalis is the most essential levator ani group muscle for fecal continence.

Attachments: Originates from the pubis’s posterior surface. It forms a U shape around the anal canal and links to the pubis on the opposite side.

Action: Tonic contraction causes the anal canal to curve anteriorly. This produces the anorectal angle, which aids in fecal continence. During feces, it is actively inhibited.

Innervation: Innervation is provided by the nerve to the levator ani and the pudendal nerve.

Some puborectalis muscle fibers (pre-rectal fibers) create another U-shaped sling that flanks the urethra in men and the urethra and vagina in women (in some textbooks they are referred to as pubovaginalis or sphincter urethrae/vaginae). These fibers are crucial in maintaining urine continence, especially after a sudden increase in intra-abdominal pressure, such as during sneezing.

Pubococcygeus

The pubococcygeus controls the levator ani complex. It is positioned on the pelvic floor between the puborectalis and the iliococcygeus.

Attachments: It refers to the structure that extends from the back surface of the pubis. It connects with the contralateral muscle in the midline of the pelvic floor.

Action: Abdominal and pelvic organ support and stability.

Innervation: Levator ani nerve and pudendal nerve branches innervate.

Iliococcygeus

The iliococcygeus is a slender muscle that is part of the levator ani muscle group on the posterolateral side.

Attachments: It originates from the ischial spines and the posterior tendinous arch of the fascia of the internal obturator muscle. It connects the anococcygeal ligament, perineum, and coccyx. It also combines with the fibers of the contralateral muscle in the pelvic floor’s midline.

Action: The pelvic floor and the anorectal canal are elevated.

Innervation: Levator ani nerve and pudendal nerve branches innervate.

Coccygeus

The coccygeus is a tiny triangular muscle found behind the levator ani muscle group.

Attachments: The inferior end of the sacrum and the coccyx give way to the ischial spines.

Action: Supports the pelvic viscera while flexing the coccyx.

Innervation: S4 and S5 anterior rami are innervated.

Blood Supply: The inferior vesical, inferior gluteal, and pudendal arteries supply blood.

Conditions And Disorders

Weak (too loose) pelvic floor muscles

Pelvic floor muscles can weaken as a result of trauma or injury, such as delivery or surgery. They can become stressed during pregnancy or as a result of misuse (frequent heavy lifting, recurrent coughing, constipation). They may become weaker as a result of hormonal changes during menopause, and they may lose strength as a natural part of aging. Diabetes may also contribute to the weakening of pelvic floor muscles.

The following conditions can result from weak pelvic floor muscles:

- Peeing or dribbling when laughing, coughing, sneezing, or lifting. It is particularly prevalent after childbirth, prostate surgery, or if your pelvis has been injured.

- Urge incontinence is the inability to hold a frequent urge to pee.

- The inability to control bowel movements is referred to as fecal incontinence.

- Anal incontinence is the inability to control when you pass gas.

- Pelvic organ prolapse refers to unsupported pelvic organs such as your uterus, rectum, and bladder bulging into or protruding from the opening of your vagina. After menopause, this syndrome is more common among AFAB people, such as cisgender women.

Struggling to regulate when you urinate, poop, or pass gas are common signs and symptoms of weaker pelvic floor muscles.

Too tight pelvic muscles

Less is known about the diseases related to too tight pelvic muscles, often known as hypertonic pelvic floor. However, having pelvic muscles with insufficient give can cause constipation or difficulty moving your bowels, pelvic pain, back or hip/leg pain, uncomfortable intercourse, and difficulties peeing, as well as urinary urgency/frequency.

Tight pelvic muscles can be caused by sexual trauma, other types of trauma or accidents, childbirth, stress, and other gynecologic problems.

Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

Pelvic floor dysfunction refers to a set of indications and symptoms caused by faulty pelvic floor muscle activity.

The pelvic floor muscles in women support the urethra, vagina, and anal canal. Weakness of these muscles can lead to a lack of structural support for these organs, manifesting as:

- Incontinence of the bladder

- Incontinence of feces

- Prolapse of the genitourinary tract

- Pelvic discomfort

- Sexual impotence

Obstetric trauma, advancing age, obesity, and continuous straining are all thought to be factors in pelvic floor dysfunction.

Pelvic organ prolapse

Pelvic organ prolapse is a herniation of the pelvic viscera via the accompanying orifice. Uterine prolapse through the vaginal vault, for example, or rectal prolapse through the anus. The illness is associated with pelvic floor weakness. Over-distension of the muscle can cause this weakening over time. Non-obstetric risk factors for developing pelvic floor dysfunction and eventual pelvic organ prolapse include chronic coughing, obesity, smoking, ethnicity, age, and a history of connective tissue condition. Obstetric risk factors include multiparity, prolonged labor, precipitous labor, and surgical vaginal delivery. A history of long-term hard lifting may also raise the likelihood of developing pelvic floor weakness and consequent organ prolapse.

Women who have pelvic organ prolapse may feel a lump bulging from the vaginal entrance. They may have an anterior wall prolapse combined with a prolapsed bladder (cystocele), resulting in urine retention symptoms. They may also have a posterior wall prolapse with a rectal wall bulge (rectocele), which causes constipation. Others may develop uterine prolapse, a condition in which the cervix extends through the vaginal opening. Even women who have had their uterus removed (hysterectomy) may experience vaginal vault prolapse due to a poorly suspended vaginal vault.

Rectal prolapse can affect both men and women. This is a painful condition in which either the rectal mucosa or the entire rectum can descend through the anus. The majority of the risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse also enhance the likelihood of developing rectal prolapse.

Exercises

Benefits

The pelvic floor, like other muscles in your body, works best when it is strong and able to fully relax after a full contraction. Strengthening the pelvic floor may be beneficial. The bladder, bowels, and uterus are all supported by Trusted Source. It can also aid with bowel and bladder control.

Improvements in pelvic floor function may also improve overall quality of life.

If you have pelvic floor prolapse, for example, strengthening the pelvic floor muscles can help trusted Sources decrease the severity of symptoms such as:

- Urine leakage

- Incontinence

- Pelvic pressure

- Lower backache

A pelvic floor strengthening program may also result in improved sex.

Some study indicates a link between male sexual function and pelvic floor function. Researchers specifically mention how pelvic floor physical therapy may help with erectile dysfunction and ejaculation issues.

Furthermore, for some women with vaginas, frequently squeezing or flexing the pelvic floor muscles may improve sexual feeling and function.

Finally, as part of a therapy strategy for overactive bladder, the American Urological Association suggests pelvic floor muscle exercise. The purpose of this therapy is to reduce incontinence by inhibiting involuntary bladder spasms.

Kegel exercises

Incontinence, as well as pelvic organ or rectal prolapse, can result from weakened pelvic floor muscles. Some exercises can help with problems like urine leaks or bowel control. those are frequently advised to undertake Kegel exercises, also known as pelvic floor exercises, during pregnancy or after childbirth to prevent urinary incontinence and to assist those who have difficulties achieving orgasm following pregnancy.

Kegel exercise guidelines

The purpose of Kegel exercises is to isolate and develop the pelvic floor muscles. Stopping the process of urination in the middle is a fantastic approach to isolating these muscles. The pelvic floor muscles are the ones that are recruited throughout this process. These are also the muscles that are used.

Empty your bladder before beginning the activity. Then, lying on your back, tense the pelvic floor muscles that you recognized before. After five seconds of holding the contraction, let go for five more. Rep 4 to 5 times more, up to 3 times per day. Once you’re comfortable holding each contraction and relaxation for 5 seconds, raise the holding time to 10 seconds.

Avoid using your abdominal, thigh, or buttock muscles during this process, and keep your breathing open. Keep in mind that you should not employ Kegel movements to start and stop your urine stream daily. Performing these activities while emptying your bladder can weaken your muscles, resulting in inadequate bladder emptying and urinary tract infections. Let’s get started by lying on your back with your knees bent and your feet flat on the ground. As you become more comfortable, challenge yourself by attempting this exercise while sitting or standing. You’ve got this!

Quick flick Kegels

Crouch describes the fast flick Kegel demands quick pelvic floor contractions to assist in engaging the muscles faster and stronger to stop leaks when sneezing or coughing.

- To begin, lie on your back with your knees bent and your feet flat on the ground as this exercise becomes easier, attempt it while sitting or standing.

- Using the guidelines provided above, locate your pelvic floor muscles.

- Exhale, bring your navel to your spine, and quickly tighten and relax your pelvic floor muscles. Aim for 1 second of contraction followed by 1 second of release.

- Maintain a steady breathing pattern throughout.

- Perform the fast flip for 10 repetitions, then take a rest of 10 seconds. Aim to complete 2-3 sets.

Heel slides

Heel slides engage the deep abdominal muscles while also stimulating pelvic floor contractions.

- Start by lying on your back, knees bent, and feet flat, and ensure that you maintain pelvic neutrality.

- Deeply inhale into your rib cage, then exhale through your mouth, allowing your ribs to collapse naturally.

- Draw your pelvic floor up, engage your core, and pull your right heel away from you. Go as far as you can without losing contact with yourself.

- Find your lowest point, inhale, and return your leg to the starting point.

- Repeat.

- Perform 10 slides up and back, then repeat with the opposite leg.

Marches (also called toe taps)

The marching exercise, like heel slides, improves core stability and promotes pelvic floor contractions.

- Start by lying on your back, knees bent, and feet flat, and ensure that you maintain pelvic neutrality.

- Exhale through your lips after inhaling into your rib cage, allowing your ribs to naturally contract.

- Draw your pelvic floor up and tighten your abs.

- Lift one leg slowly to a tabletop position.

- Lower this leg slowly back to the starting position.

- Rep the action, switching legs. There should be no soreness in your lower back. Your deep core must remain engaged throughout the activity.

- Alter legs 12-20 times in total.

Happy Baby Pose

When stretching and releasing is the goal, the Happy Baby Pose is an excellent addition to a pelvic floor exercise.

- Start by bending your knees while lying on the floor.

- Your knees should be 90 degrees bent toward your torso, with your feet pointed upward.

- Grasp either the outside or inside of your feet firmly.

- Adjust your knees to be slightly wider than your body. After that, raise your feet so they are level with your armpits. Check to see if your knees are higher than your ankles.

- Push your feet into your hands and flex your heels. You can hold this position for many breaths or rock gently from side to side.

Diaphragmatic breathing

Diaphragmatic breathing promotes the diaphragm-pelvic-floor functional connection. It may also assist Trusted Source in reducing stress.

- Begin by lying down on a yoga or fitness mat on the floor. You can also complete the exercise while seated.

- Do some progressive relaxation for a few seconds. Concentrate on relaxing your muscles.

- Place one hand on your stomach and the other on your chest once you’ve relaxed.

- Inhale through your nose to expand your tummy, keeping your chest relatively motionless. Then, inhale for 2-3 seconds before gently exhaling.

- Repeat many times with one hand on the chest and the other on the stomach.

Summary

The pelvic floor muscles are a group of muscles and connective tissues that support the organs in the pelvis, including the bladder, bowel, uterus, and rectum. They also help to control urination, defecation, and sexual function.

Both men and women need to have strong pelvic floor muscles for their overall health and well-being. In men, the pelvic floor muscles help to support the prostate and bladder. They also help to control ejaculation. In women, the pelvic floor muscles help to support the uterus, bladder, and bowel. They also aid in urine and feces control.

Pelvic floor dysfunction can occur in people of all genders. Numerous issues, such as pelvic organ prolapse, fecal incontinence, urine incontinence, and sexual dysfunction, may result from this.

Some things can contribute to pelvic floor dysfunction, including:

- Childbirth

- Menopause

- Aging

- specific medical conditions, including neurological disorders, diabetes, and obesity.

- Surgery, such as hysterectomy or prostate surgery

- Chronic straining, such as from constipation or lifting heavy objects

If you think you may have pelvic floor dysfunction, it is important to see a doctor or physical therapist for evaluation and treatment. There are several effective treatments available, including pelvic floor muscle exercises, biofeedback, and electrical stimulation.

Here are some tips for keeping your pelvic floor muscles healthy:

- Do pelvic floor exercises regularly.

- Maintain a healthy weight.

- Avoid smoking.

- Eat a healthy diet.

- Exercise regularly.

- Practice good posture.

- Avoid lifting heavy objects improperly.

FAQs

What does the pelvic floor do?

The pelvic floor is a group of muscles and connective tissues that support the organs in the pelvis, including the bladder, bowel, uterus, and rectum. It also assists in the regulation of urination, feces, and sexual function.

The pelvic floor muscles are also important for core stability and balance. They work with other muscles in the core, such as the abdominal muscles and the back muscles, to support the spine and pelvis

Do individuals of both genders have these muscles?

Yes, people of all genders have pelvic floor muscles. The pelvic floor is a group of muscles and connective tissues that support the organs in the pelvis, including the bladder, bowel, uterus, and rectum. The muscle also helps regulate urination, bowel movements, and sexual function.

How can I recognize if I have a weak pelvic floor?

Some signs and symptoms can indicate that your pelvic floor is weak. These include:

Urinary incontinence: Urine leaking from laughing, sneezing, coughing, or exercising.

Fecal incontinence: Leaking stool or gas.

Pelvic organ prolapse: A bulge in the vagina or rectum.

Hip, lower back, or pelvic region pain.

Difficulty emptying your bladder or bowel.

Painful sex.

How long does it take to build a strong pelvic floor?

The amount of time it takes to strengthen the pelvic floor varies from person to person. It depends on some factors, including the severity of the weakness, the type of treatment used, and the consistency of the treatment program.

Most people begin to notice some improvement in their pelvic floor strength within 4-6 weeks of starting treatment. However, it may take up to 3 months to see a major change. It is important to be patient and consistent with your treatment program to achieve the best results.

References

- Professional, C. C. M. (n.d.). Pelvic Floor Muscles. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/22729-pelvic-floor-muscles

- The Pelvic Floor – Structure – Function – Muscles – TeachMeAnatomy. (2023, January 19). TeachMeAnatomy. https://teachmeanatomy.info/pelvis/muscles/pelvic-floor/

- BSc, L. C. M. (2023, August 15). Muscles of the pelvic floor. Kenhub. https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/muscles-of-the-pelvic-floor

- Lindberg, S. (2023, August 7). 5 Pelvic Floor Exercises for Anyone and Everyone. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/fitness-exercise/pelvic-floor-exercises

10 Comments