Medial Collateral ligament Sprain

Table of Contents

What is a Medial Collateral ligament Sprain?

A strain, partial tear, or full tear of the ligament on the inside of the knee is referred to as an MCL injury(Medial Collateral ligament Sprain). It is one of the most frequent knee injuries that is mostly brought on by a valgus force.

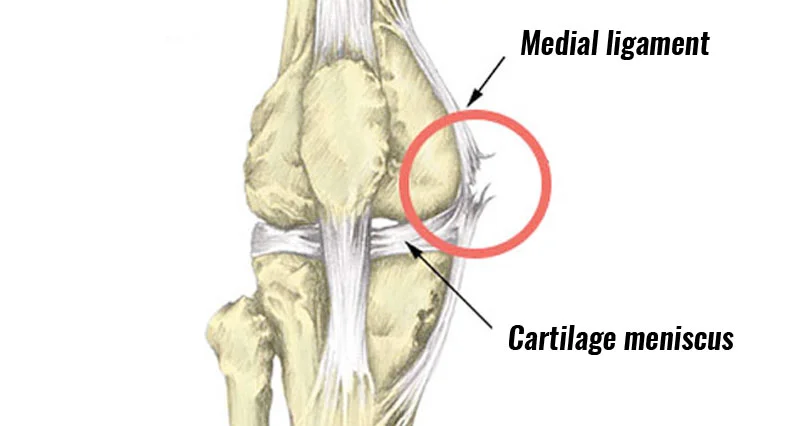

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

- Relevant On the medial side of the knee, there is a large ligament called the medial collateral ligament. For more therapeutically applicable knee anatomy One of the four ligaments necessary for preserving the mechanical stability of the joint is the medial collateral ligament (MCL).joint stability in the knee. From the medial aspect of the extensor to the entire medial side of the knee, the ligamentous sleeve runs. the device that attaches to the back of the knee.

- A ligament’s primary role is to limit excessive motion by having a limited amount of elastic fibers and a lot of collagen fibers. however, it also serves as a source of proprioception. Its purpose is to deflect forces coming from the knee’s outside surface and So, stop the medial joint component from spreading when stressed. Although proprioceptors are found in ligaments, they are also joint capsules and muscles. These proprioceptors keep track of our motions, the position of our limbs in space, and the amount of effort we exercise when lifting things.

Causes of MCL Sprain?

- Most MCL injuries occur when the foot makes contact with the outside of the knee, lower thigh, or upper leg. grounded and immobile. Due to the impact and a coupled movement, the MCL on the inside of the knee will get stressed. flexion, valgus, or external rotation will cause fiber tears. The athlete may experience sharp pain at first and feel or hear a sound of popping or tearing. Most often, the deep section of the ligament is destroyed first, which may result in injury to the medial meniscus. or injury to the ACL (anterior cruciate ligament).

Symptoms of MCL Sprain:

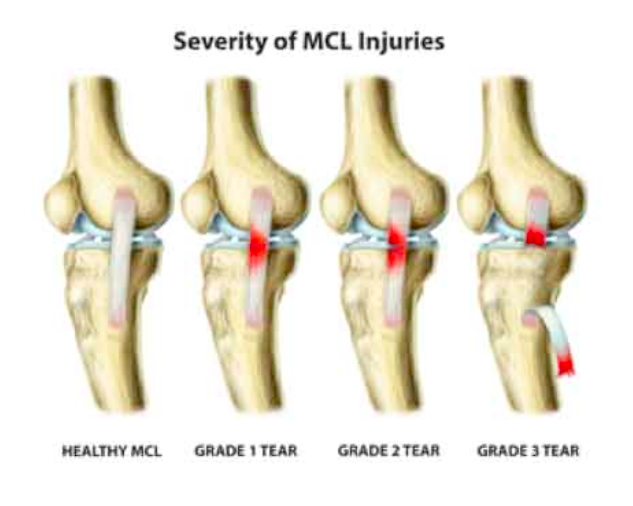

- The grade of the MCL damage is I, II, or III, just as all other ligament injuries.

- Less than 10% of the collagen fibers are ripped in a grade I tear, which has some discomfort but no instability. several of the Patients experience pain when we press on the outside of a slightly bent knee, but no other symptoms are present. Grade II tears are divided into grades II– (closer to grade I) and II+ (closer to grade III) based on the symptoms they exhibit.

- grade III, however, both of them are considered to be delicate but unsteady. Compared to before, the discomfort and swelling are more severe.

- Several of the Patients experience pain when we press on the outside of a slightly bent knee, but no other symptoms are present. Grade II tears differ in their symptoms, so they are broken down. Grade I wounds. Patients report pain and considerable tenderness on the inside of their knees when the knee is stressed (as for grade I). considerable joint laxity is seen in the knee. Since the MCL has completely ruptured in a grade III tear, instability results, it should be obvious from this. Patients experience severe pain and enlargement at the MCL. They frequently struggle to bend their knees.

- As previously mentioned, a grade III tear causes instability, there is joint laxity when the knee is stressed (as stated above). An additional scale is used for Grade III MCL damage. evaluate the instability’s severity. The degree of joint separation measured by the 30° valgus test is used to describe these. In contrast to grade III tears, which occur at a soft endpoint with valgus stress, grade I and grade II injuries have endpoints that are clearly defined. testing Less than 10% of the collagen fibers are torn in a grade I tear. The symptoms of Grade II tears differ, therefore they are grade II-, which is more similar to grade I, and grade II+. (closer to grade III). It follows that a grade III tear is a serious injury. MCL rupture that is total. Patients report soreness, moderate joint laxity, and severe tenderness when the knee is pressured (as in grade I). inside of the knee. Patients who have a grade III MCL tear experience severe pain and edema over the MCL. The majority of the time, they have a challenge in bending the knee. Instability is another characteristic of a grade III tear. When the knee is strained (as explained Joint laxity is present ).

Differential Diagnosis

- To rule out injuries that could produce the same symptoms as a knee MCL injury, a differential diagnosis is required. These wounds are:

- Torn or damaged medial meniscus cruciate ligament.

- Anterior (ACL) tear –Broken.

- tibial plateau fracture or harm.

- to the femur subluxation/dislocation of the patella.

- a knee injury to the middle.

- fracture of the distal femur in children.

- Damage to the structures at the posteromedial corners.

- An accurate diagnosis will be ensured with the aid of a physical examination. Because of this, an MCL sprain and a medial meniscal rupture can be confused. Similar to a sprain, a tear results in joint pain. A medial meniscal tear can be detected with a valgus laxity evaluation. from an MCL sprain of grade II or III. The medial meniscus is torn if there is an opening on the joint line. An MCL grade I is harder to distinguish from a medial meniscal tear. An MRI or observation of the differences can be used to differentiate. wait a few weeks with patience. A tenderness that results from an MCL sprain typically goes away, although it stays after meniscal damage.

- The presence of discomfort in the absence of aberrant valgus laxity may indicate a medial knee contusion. If the soreness is localized The cause is more likely to be patellar dislocation or injury to the medial retinaculum close to the patella or adductor tubercle. subluxation. The patellar apprehension test can be used to distinguish between patellar instability and an MCL sprain. a fruitful outcome means that the patella is unstable. A mild stress-testing radiograph can establish whether a distal femoral fracture rather than an MCL is present in a pediatric patient sprain.

Diagnostic Procedure

- The patient’s anamnesis is crucial for pinpointing the location of the pain. The therapist must feel discomfort or soft-tissue swelling after evaluating where it aches. He must feel the knee joint to determine that. The medial side of the knee is where the discomfort is most frequently concentrated. Additionally, there will be soft tissue edema. As previously mentioned, there are three types of MCL tears. During stress testing of the patient’s knee joint, the grade is based on the intensity of the pain or the extent of the joint space opening.

- Test for MCL valgus stress

- Anteromedial drawer test

- Swain test

Outcome Measures

To measure pain, functioning, impairment, and changes in the patient’s status as a result of treatment, clinicians employ a variety of devices. They make use of a validated activity scale, a validated general health questionnaire, and a validated patient-reported outcome measure.

Examination

- To determine whether the MCL is the only structure that has been injured or whether other structures have also been harmed, a clinical evaluation is crucial. The patient’s account of the injury provides a wealth of information, to start. In order to compare the two legs, the contralateral knee should also be checked. Finding any edema and pinpointing its location is crucial while looking over the knee. Typically, the medial portion of the knee will have a discrete swelling. It’s crucial to palpate the MCL along the medial aspect of the knee and feel for tenderness, noting where the most intense pain is (femoral vs. tibial sides).

- It’s also crucial to note that the knee should be examined as soon as possible following an accident before any muscular spasms can develop. Unfortunately, this possibility is only accessible if doctors were nearby when the damage occurred. It is rarely essential to perform an examination under anesthesia on patients who have significant muscle spasms; instead, a 24-hour period of immobilization for relaxing is typically sufficient. The two-part valgus stress test can be performed to evaluate the medial collateral ligament itself. The knee is first given valgus stress with the knee fully extended. Second, the identical test is run with the knee flexed by 30 degrees. In order to gauge the widening of the medial joint space and have a sense of a reliable endpoint, it is essential to test the MCL with the knee in both 0° and 30° of flexion. It is crucial that the foot remains in external rotation throughout the test to prevent the examiner from overestimating the degree of laxity caused by the knee shifting from internal to external rotation.

- The Swain test may be used as a second test to look at the medial collateral ligament. This test looks at the knee’s rotatory instability and chronic damage. The test is carried out by externally twisting the tibia while flexing the knee to 90 degrees. The collateral ligaments are constricted while the cruciate is relaxed when the knee is in this position. An injury to the MCL complex is likely when discomfort is experienced on the medial side of the knee. The anteromedial drawer test is a different test that can be used to determine the degree of rotational stability present and whether the lesion just affects the superficial MCL and deep MCL. The knee’s anterior drawer test A crucial tool for examining a medial collateral ligament injury is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Currently, it is the only tool capable of displaying morphological and functional joint damage.

Treatment

Medical Treatment

- Every ligament injury receives the same first three grades. Grade I is a sprain, Grade II is a partial ligament tear, and Grade III is a full ligament tear. A grade four damage to the MCL, also known as a medial column injury, is described by certain doctors. Surgery might be necessary when the lesion affects more than simply the medial collateral ligament (MCL). Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries, bone bruising, lateral collateral ligament (LCL) injuries, lateral and medial meniscus tears, as well as posterior cruciate ligament injuries, are injuries that frequently occur in conjunction with medial collateral ligament injuries. (PCL). High-grade MCL rips are most frequently linked to ACL disturbances.

- We can also differentiate the grades according to laxity and pain :

- Grade I injuries produce pain without laxity (<3 mm gapping at a corresponding joint line)

- Grade II injuries are often more painful, with 5-10 mm of laxity ;

- Grade III injuries may be less painful as the ligament is completely ruptured, and this allows significant laxity (>10 mm) on testing

- The majority of grade I and II MCL injury treatments are non-operative and involve a physical rehabilitation regimen.

- Results of non-operative treatment are less clear when treating grade III injuries. Whether the MCL is injured alone or in combination with other ligaments, where it is injured (more to the tibial or femoral side of the ligament), and whether posterior structures are involved all affect the course of treatment. Finding the precise site of the damage via MRI imaging can aid in determining the best course of treatment. Therefore, many ligament-involved injuries (grade 4) might need reconstruction or augmentation right away. Different methods can be used for augmentation.

Physical Therapy Treatment

- Surgery is rarely necessary for the treatment of medial collateral ligament damage. The medial collateral ligament, which is extracapsular, seems to have a reasonably good chance of healing. The MCL tear may be treated surgically in circumstances when instability persists despite nonoperative treatment or instances of persistent instability following ACL and/or PCL restoration.

- Bracing or immobilization are successful non-operative treatments for the most isolated MCL injuries. Patients will be able to resume their prior level of activity with the help of certain straightforward therapy procedures and rehabilitation. Most treatment plans emphasize restoring range of motion quickly, minimizing swelling, allowing patients to bear weight safely, and moving on to strengthening and stability activities. Having a patient or athlete resume full activities is the main objective.

- The guiding concepts of rehabilitation are: to reduce edema to begin M. Quadriceps activation in the first few days to weeks following injury. should make an effort to quickly restore the knee’s range of motion A medial knee injury can be categorized into three categories.

Grade 1

- Isolated grade I injuries are typically treated non-operatively. Icepack, compression, and elevation should be used as much as possible within the first 48 hours. The standard course of treatment for incomplete tears of the MCL is temporary immobilization and the use of crutches to manage pain. Within a few days of the discomfort and swelling subsiding, incremental resistive workouts that are isometric, isotonic, and eventually isokinetic are started. The amount of pain must be considered while determining how quickly you should bear weight.

Grade II/III

- injuries should focus on protecting the ligament’s ends so they can mend without being constantly disturbed. To ensure that the injury can heal properly, one should refrain from placing large demands on the healing structures for three to four weeks after the damage. Whether a grade III injury is isolated or coexists with other ligamentous injuries will affect how it is treated. The typical strategy is to rehab the medial knee injury first so it can heal in accordance with the standards for an isolated medial knee injury in cases of grade III medial knee injuries coupled with additional injuries, such as an ACL tear.

Rehabilitation

- A non-operative treatment’s rehabilitation process can be divided into four stages: The first phase lasts one to two weeks. The goal of phase one is to reduce knee swelling by using ice for 15 minutes every two hours. (first two days). The frequency can be decreased to three times each day for the remainder of the week. Depending on your symptoms, use ice as tolerated and as needed. The patient must start off using crutches. Early weight bearing is advised since patients can gradually lessen their reliance on crutches as they increase their weight bearing. After that, let the patient use one crutch only, and only when it is possible for them to walk normally. Maintaining the capacity to straighten and bend the knee from 0° to 90° is another goal of this phase.

- It is advised to perform pain-free stretches for the calf, groin, quad, and hamstring muscles in particular. The therapeutic exercises are the final. Starting with static strengthening exercises for the patient (as soon as pain allows it). They include workouts like quadriceps sets, straight leg lifts, range-of-motion drills, sitting hip flexion, sideways hip abduction, standing hip extension, and standing and hamstring curls, for example. Patients are urged to use a stationary bike as soon as they are able to tolerate it to increase their knee’s range of motion. This would guarantee a quicker recuperation. On the stationary bike, duration and effort are increased as tolerated. Since each patient is unique, these are obviously not the required standard workouts for patients.

- Phase 2 starts in the third week. The range of motion goals is the same as they were in phase one. Biking for 20 minutes is the next step. Increase the resistance as much as the patient can handle it. Cycling will promote recovery, re-establish strength, and preserve aerobic fitness. Other exercises that the physiotherapist can recommend include step-ups, double-leg presses, and hamstring curls. As a precaution, the patient has the possibility to be evaluated by a physician every three weeks to verify the healing of the ligament.

- Week five marks the start of phase three. Full weight bearing on the damaged knee is the main objective of this stage. When walking with complete weight bearing is achievable and there is no gait distortion, stop using a brace. A complete range of motion must be attained, and it must be symmetrical with the uninjured knee. Similar to phase two, therapeutic exercises are used. They might aid development. To reduce swelling, we keep using cold therapy and compression. You can start practicing your balance and proprioception at this time. The patient can continue using the stepper or, if it’s possible, start swimming to maintain their cardio fitness.

- The start of phase four can happen six weeks following the knee injury. Stop wearing the brace when walking. For at least three months during the competitive season, athletes can compete while wearing the brace. It is still necessary to use cold therapy. Therapeutic exercises are more concentrated on everyday motions or movements utilized in a particular sport. Increase the strength of the strengthening exercises, and switch from double-leg exercises to single-leg activities. The patient may resume running at a comfortable pace (watch out for unexpected changes in the patient’s course). It is advisable to resume competition as soon as a complete range of motion and strength have been regained and the patient has passed a sport-specific functional exam. After an injury, using cold therapy lowers swelling, but it has little effect on the ligament’s ability to mend.

Prevention

- Like in many other situations, adequate warming up helps to protect the medial collateral ligament from damage. Programs for warming up the muscles, particularly neuromuscular ones, appear to be effective in lowering the number of injuries involving the knee joint. Programs that target the leg and core muscles, balance, landing methods, and optimal joint alignment reduce excessive knee valgus and lateral trunk displacement. These two criteria are risk factors for this kind of injury, as was already indicated. The warm-up may consist of drills like side-cutting and single-leg landings. These are really dangerous moves. To guarantee that the knee can respond to these motions effectively, regulate them throughout the warm-up.

FAQs

What is a sprain of the medial collateral ligament?

Your tibia, or shin bone, is stabilized by this ligament. Usually, pressure or stress on the outside of the knee results in MCL damage. This ligament is frequently hurt during a football tackle to the outside of the knee. A stretch, partial tear, or full tear of the MCL are all examples of ligament injuries.

What causes an MCL sprain?

A twisting motion or a blow to the outside of the knee might cause your knee to be forced beyond its normal range of motion, injuring the MCL. If you catch your foot in the ground, such as in a hole or on turf, and then try to turn to the side, away from the planted leg, you could also sprain your MCL.

How long does MCL sprain healing take?

If you have a grade 1 MCL sprain, it can take you as little as 3 weeks to fully recover. You should plan on recovering for at least 4+ weeks if you have an MCL sprain of grade 2-3. Fortunately, MCL tears don’t often need surgery, so they heal faster than some other sports injuries.

What side effects can an MCL sprain cause?

Even after treatment, the joint may remain unstable if the ruptured MCL also caused tears in one or more additional knee ligaments. Fractures, stiffness, and loss of motion, as well as harm to the nerves and blood vessels, are further concerns.

What are the danger signs of an MCL sprain?

Bending over or carrying large objects, like when weight lifting. landing incorrectly, like while jumping in volleyball, on the knee. Knee hyperextension, such as when skiing. by subjecting the knee to repeated strain, which causes the ligament to become less elastic. (like a worn-out rubber band).