Lyme arthritis

Table of Contents

What is Lyme arthritis?

Lyme disease frequently leads to Lyme arthritis. Although Lyme disease might affect many organs, such as the heart & nervous system, joint involvement tends to be the most common & persistent manifestation, resulting in joint swelling & pain. About 60 % of patients who are infected with Lyme develop arthritis unless they receive antibiotics.

Lyme disease, the very common tick-borne disease in the United States, is caused by infection with a spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Transmitted by the Ixodes tick, it is an important cause of arthritis in endemic areas, & its incidence has been increasing. Lyme disease has been reported in all 50 states, but endemic areas, involving Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Connecticut, Delaware, & Rhode Island, account for 93 percent of all cases annually. There is a bimodal age distribution in children aged 5 to 9 years & adults aged 55 to 59 years. Children infected by B. burgdorferi are more likely than adults to have arthritis as the initial manifestation of the condition. Whereas it is important to determine a history of a tick bite, up to 30 % of people do not remember being bitten.

In most, Lyme arthritis resolves after 1 month of treatment with an oral antibiotic, such as doxycycline or amoxicillin. Individuals with persistent symptoms despite an oral antibiotic generally respond to treatment with an intravenous antibiotic for 30 days. nevertheless, about 10 % of those with Lyme arthritis fail to respond to antibiotic treatment, for reasons that have long been unclear.

There are three phases of the infection—

- early localized,

- early disseminated, &

- late.

Arthritis, which is the most distinguishing sign of late-stage Lyme disease, develops in up to 60 % of untreated Lyme patients & is manifested months after disease onset. After infection, spirochetes are disseminated & invade synovial joints, resulting in a profound immune response, the same as that seen in bacterial arthritis. Patients with Lyme arthritis present with migratory polyarthralgia that also includes bursae & tendons. This usually evolves into a monoarticular process & usually involves single large joints. More than 90 % of patients report knee inflammation, but other affected joints involve the wrist, elbow, ankle, & hip. The Centers for Disease Control & Prevention has defined Lyme arthritis as “recurrent, brief attacks (weeks or months) of objective joint swelling in one or a few joints, sometimes followed by chronic arthritis in only one or a few joints.”

The rash is frequently overlooked by patients & is generally not present in patients when they present with arthritis. Nevertheless, fever is noted in up to 50 % of all children who have Lyme arthritis. Clinically, the arthritis is the same as other inflammatory processes of the joint & includes warmth, erythema, swelling, & pain in the motion of the joints; however, the effusion is usually large & out of proportion to the patient’s complaints. The effusion also usually recurs after aspiration, even when the joint is appropriately treated.

What are the causes of Lyme arthritis?

Lyme arthritis is caused by Lyme disease. The cause of the disease is the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, which is transmitted by the bite of the tick Ixodes ricinus. Most ticks are not infected & hence most tick bites do not result in infection most infections, if apparent as erythema migrans, do not progress to later stages of the disease involving Lyme arthritis.

This is the case especially if early stages, including erythema migrans, have been treated with antibiotics. Thus, although Lyme borreliosis, in the form of erythema migrans, might occurs in up to 1 in 1000 children each year, the occurrence of Lyme arthritis, the late manifestation of the disease, is a rare event.

When that happens, the joints particularly large ones like the knee become swollen & painful. Typically, by the time the late-stage symptoms like Lyme arthritis show up, the early-stage signs of Lyme disease (like fever & rash) have gone away.

What are the symptoms of Lyme arthritis?

The main feature of Lyme arthritis is the obvious swelling of one or a few joints. While the knees are affected most frequently, other large joints such as the shoulder, ankle, elbow, jaw, wrist, & hip can also be involved. The joint might feel warm to the touch or cause pain during movement. Joint swelling can come & go or move between joints, & it might be difficult to detect in the shoulder, hip, or jaw. Lyme arthritis significantly develops within one to a few months after infection.

By the time late-stage Lyme disease has occurred into arthritis symptoms, the pain feels different from those early flu-like symptoms.

The early stages of Lyme disease are much more consistent with a viral infection where the patient is kind of hurt all over. Maybe some achiness in the joints & general discomfort, but it’s more generalized & there’s not associated swelling,” Laura Lewandowski, MD, a clinical fellow with the National Institute of Arthritis & Musculoskeletal & Skin Diseases’ Systemic Autoimmunity Branch.

The following are some traits that distinguish late-stage Lyme arthritis from other types of arthritis:

- Lyme arthritis is not symmetric on both sides. This is unlike many kinds of inflammatory arthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis.

- Lyme arthritis generally causes pain in only a few joints. It normally causes pain in fewer than five joints at a time — sometimes even in just one joint.

- Lyme arthritis most frequently affects the knees & ankle, but it can affect other joints too.

- Lyme arthritis pain isn’t constant. And usually isn’t enough to keep a patient from walking.

- Lyme arthritis pain could seem more painful than it feels. “Patient can get a very swollen knee, but that, paradoxically, is not very painful.”

Nevertheless, the signs and symptoms of Lyme arthritis can mimic other types of arthritis, which can make it tricky to diagnose, especially if the patient never found a tick or has reason to suspect they have Lyme disease.

What is the pathogenesis of Lyme arthritis?

In the northeastern USA, B. burgdorferi strains frequently disseminate to joints, tendons, or bursae early in the infection. Although this event is frequently asymptomatic, transient or migratory arthralgias might occur at that time. Lyme arthritis, a late disease manifestation, generally occurs months later accompanied by intense innate & adaptive immune responses. The adaptive immune response leads to the production of specific antibodies, which opsonize the organism, facilitating phagocytosis & effective spirochetal killing

With appropriate oral &, if required, IV antibiotic therapy, spirochetes are eradicated, & joint inflammation resolves in the great majority of patients. Nevertheless, in a small percentage of patients, particularly in those who were infected with highly inflammatory B. burgdorferi RST1 strains, synovial inflammation persists for months or several years despite receiving oral & intravenous antibiotic therapy for 2 or 3 months, called antibiotic-refractory arthritis. A refractory outcome is likely to need multiple factors, & might include some combination of pathogen-associated, genetic, & immunologic factors.

Although antibiotic-refractory arthritis is related to highly inflammatory strains of B. burgdorferi, tenacious infection in the post-antibiotic period does not appear to play role in this outcome. PCR testing of synovial fluid for B. burgdorferi DNA, which is frequently positive prior to treatment, is usually negative after antibiotic treatment, & both culture & PCR testing of synovial tissue have been uniformly negative from synovectomy specimens acquire months to years after antibiotic therapy.

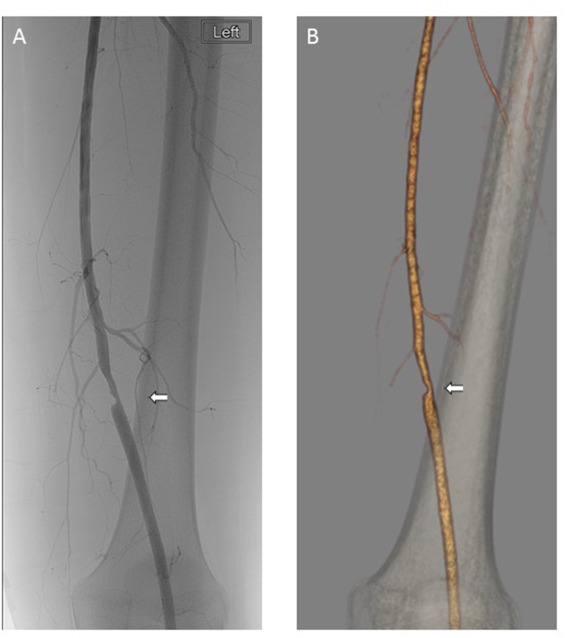

Rather, excessive inflammation during the infection, infection-induced autoimmunity, & failure to down-regulate inflammatory responses appropriately after spirochetal killing appear to be critical factors. Specifically, antibiotic-refractory arthritis is related to specific HLA-DR alleles that bind an epitope of B. burgdorferi outer-surface protein A (OspA), guiding to particularly strong Th1 responses. Additionally, this outcome occurs more frequently in patients with a TLR1 polymorphism (1805GG) that is found in half of the European Caucasian population, which leads to exceptionally high levels of cytokines & chemokines in affected joints. As evidence of immune dysregulation, patients with antibiotic-refractory arthritis have low frequencies of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in synovial fluid; the lower the frequency, the longer the post-treatment time period of arthritis. In MyD88 -/- mice, spirochetal antigens are retained on cartilage surfaces, but it is not yet clear whether retained spirochetal antigens play a role in the post-antibiotic phase in human Lyme arthritis. Finally, a novel human autoantigen, endothelial cell growth factor, was recently identified as a target of T- & B-cell responses in a subset of patients with Lyme disease, which provides the first direct evidence for autoimmune T- & B-cell responses in this illness. Additionally, synovial tissue in Lyme arthritis frequently shows obliterative microvascular lesions, & this finding correlates directly with the magnitude of ECGF antibody responses.

In spite of heightened immune reactivity, antibiotic-refractory arthritis eventually resolves. Thus, it appears that spirochetal killing, either by the immune system or with the assistance of antibiotic therapy, removes the innate immune “danger” signals. Without these signals, the adaptive immune response to autoantigens eventually regains homeostasis, & arthritis resolves. This process might be facilitated by therapy with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs).

What is the prevalence of Lyme arthritis?

Only a few children with arthritis have Lyme arthritis. Nevertheless, Lyme arthritis is probably the most often arthritis occurring after bacterial infection in children & adolescents in Europe. It rarely happens before the age of 4 years & is therefore primarily a disease of school children.

It occurs in all areas of Europe but is prevalent in Middle Europe & southern Scandinavia around the Baltic Sea. Although transmission depends on the bite of infected ticks, which are active from April to October depending on environmental temperature & humidity, Lyme arthritis might start at any time during the year because of the long & variable time between the infecting tick bite and the onset of joint swelling.

Lyme arthritis is an infectious disease & is not inherited. In addition, Lyme arthritis resistant to antibiotic management has been associated with certain genetic markers but the precise mechanisms of this predisposition are not known.

What is the differential diagnosis of Lyme arthritis?

In addition to serologic testing, clinical features might distinguish Lyme arthritis from other arthritides. A common concern is a mechanical injury in an active individual, & therefore, orthopedists are frequently the first specialist to see a patient with Lyme arthritis. Nevertheless, the clinical picture of Lyme arthritis is most like reactive arthritis in adults or pauciarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis in children, & serologic testing is essential to distinguish Lyme arthritis from these entities. Children might have a more acute presentation, with higher synovial WBC counts which might suggest a diagnosis of acute septic arthritis. Nevertheless, Lyme arthritis typically causes only minimal pain with a passive range of motion, & involvement of more than one joint (currently or by history) might help to distinguish Lyme arthritis from septic bacterial arthritis. Lyme arthritis rarely, if ever causes chronic, symmetrical polyarthritis, which helps to differentiate Lyme arthritis from rheumatoid arthritis. Fibromyalgia is sometimes misdiagnosed as Lyme disease, but patients with fibromyalgia generally have diffuse pain, & they lack objective evidence of joint inflammation.

Other inflammatory arthritides, such as rheumatoid arthritis, reactive arthritis, or psoriatic arthritis might develop within months after Lyme disease, seemingly triggered by the spirochetal infection. Thus, these systems should be considered in the differential diagnosis. In endemic areas, the concomitant positive serologic consequence for Lyme disease in patients with other inflammatory arthritides can present a diagnostic challenge, since antibody responses to B. burgdorferi following antibiotic-treated Lyme arthritis significantly persist for many years.

How to prevent Lyme arthritis?

In European countries where ticks are found, it is hard to prevent children from acquiring a tick. Nevertheless, most of the time the causative organism Borrelia burgdorferi is not transmitted straight away after the tick bite, but only several hours & up to one day later, when the bacterium has attained the salivary glands of the tick & is excreted with saliva into the host. Ticks fasten to their hosts for 3 to 5 days, eating on the host’s blood. If children are screened every evening in the summer for attached ticks & if these ticks are removed immediately, the transmission of Borrelia burgdorferi is very unlikely.

Preventive management with antibiotics following a tick bite is not advocated. Nevertheless, when the early manifestation of erythema migrans happens, it should be treated with antibiotics. This treatment will stop the further proliferation of the bacterium & prevent Lyme arthritis. In the USA, a vaccine against a single strain of Borrelia burgdoferi had been produced, but it was withdrawn from the market for economic reasons. This vaccine is not useful in Europe because of strain variations.

What is the diagnostic procedure for Lyme arthritis?

Physical examination

Patients with Lyme arthritis significantly have the following features on physical examination:

Monoarthritis or oligoarthritis most commonly affects the knees, but other large or small joints may be affected, such as the ankle, shoulder, elbow, or wrist. Affected knees may have very large effusions with warmth, but in contrast with typical bacterial (e.g., staphylococcal) septic arthritis, they are not particularly painful with a range of motion or weight bearing. Baker’s cysts might be present in the knees given the large size of effusions.

Fever is usually not present.

Serologic testing for Lyme disease

The main test in diagnosing Lyme arthritis is serologic testing. In the USA, the CDC currently advocates a two-test approach in which samples are first tested for antibodies to B. burgdorferi by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), & those with equivocal or positive results are subsequently tested by Western blotting (WB), with findings interpreted according to the CDC criteria. In contrast with early infection, when some patients might be seronegative, all patients with Lyme arthritis, a late disease manifestation, have positive serologic results for IgG antibodies to B. burgdorferi, with the expansion of the feedback to many spirochetal proteins. When serum samples were tested with microarrays of more than 1200 spirochetal proteins, 120 proteins, primarily outer-membrane lipoproteins, were found to be immunogenic, & patients with Lyme arthritis had IgG reactivity to as many as 89 proteins. Serologic testing should be done only in serum, as serologic tests in synovial fluid are not accurate.

In addition to IgG antibody responses to B. burgdorferi, patients with Lyme arthritis might also have low-titer IgM reactivity with the spirochete. On the other hand, a positive IgM feedback alone in a patient with arthritis is likely to be a false-positive feedback or one indicative of previous, antibiotic-treated early Lyme disease in patients who now have another type of arthritis. Therefore, positive IgM antibody feedback alone should not be used to support the diagnosis of Lyme arthritis. After spirochetal killing with antibiotics, anti-spirochetal antibody titers decline gradually, but both the IgG & IgM responses in patients with past Lyme arthritis might remain positive for years, which appears to be an indicator of immune memory rather than active infection. We have not observed re-infection in patients with the expanded immune response produced in patients with Lyme arthritis. Therefore, a persistent, expanded IgG antibody feedback seems to be protective against re-infection, whereas the limited response seen in patients with erythema migrans is not.

Synovial Fluid PCR for B. burgdorferi

Although reported in a few patients, it is exceedingly hard to culture B. burgdorferi from synovial joint fluid in patients with Lyme arthritis. This is presumably because of the fact that joint fluid, with its many inflammatory mediators, is an extremely hostile environment. In spiked cultures, adding small amounts of joint fluid results in the rapid killing of spirochetes. In contrast, polymerase chain reaction testing of synovial fluid for B. burgdorferi DNA frequently yields positive outcomes before antibiotic therapy,& usually becomes negative following antibiotic treatment. Nevertheless, spirochetal DNA might persist after the spirochetal killing, which limits its use as a test for active infection. Moreover, PCR testing has not been standardized for routine clinical usage. Therefore, in most cases, the appropriate clinical picture & a positive serologic outcome are sufficient for the diagnosis of Lyme arthritis, & PCR testing serves as an optional test to further support the diagnosis.

Synovial Fluid Analysis, Imaging, & Other Tests

On presentation, joint aspiration is generally done for diagnostic purposes to rule out the presence of other arthritides such as crystalline arthropathy or staphylococcal septic arthritis. Joint fluid white cell counts are generally inflammatory in the range (of 10,000 to 25,000 cells/mm3), but cell counts as low as 500 or as high as 100,000 cells/mm3 have been reported. Although tests for rheumatoid factor or antinuclear antibodies typically yield negative results, antinuclear antibodies with low titer might be detected. Peripheral white blood cell (WBC) counts are usually within the normal range, but inflammatory markers, such as ESR & CRP, might be elevated. Imaging studies are not needed for diagnosis or are not typically performed. The important reason for imaging studies in Lyme arthritis is when there are concerns for an alternative diagnosis.

In patients with Lyme arthritis, plain films, MRI scanning or ultrasound typically show non-specific joint effusions, while MRI studies use contrast dye, which might display synovial thickening or enhancement. In adult patients, imaging studies might show co-incidental degenerative changes or chronic mechanical injuries, but these abnormalities would not be expected to cause significant synovitis or inflammation. Lyme arthritis is not rapidly erosive, but with longer arthritis durations, joint damage can be seen in radiographic studies. Finally, MRI scanning might be useful in the planning of synovectomies by determining the extent of synovitis within the joint.

Lyme False Negatives and False Positives

The tests have been criticized by some for showing false negatives when a test says the patient doesn’t have Lyme disease when you actually do during the early stages of Lyme. But at the end, where Lyme arthritis comes along, those tests should definitely be positive.

False positive Lyme test outcome can also throw a wrench into a Lyme arthritis diagnosis. This is when the test says the patient has Lyme disease but you actually don’t.

In patients who have infectious mononucleosis or test positive for an antibody called rheumatoid factor (RF), those other conditions could cross-react with the Western blot test & make it look like the patient have Lyme when it’s actually something else, according to a study in Pediatric Rheumatology. RF is related to rheumatoid arthritis, so there’s a chance that rheumatoid arthritis could be the real root of joint pain.

Nevertheless, rheumatoid arthritis seems to be symmetric, but Lyme arthritis rarely is, which could be a sign that it isn’t Lyme after all.

If antibiotics for Lyme treatment don’t appear to be working, a doctor can test fluids from the knee joint for signs of Lyme. A negative test would show the Lyme has cleared out & something else is causing the pain.

In rare instances, the initial Lyme infection can trigger a different autoimmune condition. In that case, the antibiotics should be dropped in favor of a new management program such as anti-inflammatory drugs.

What is the treatment protocol for Lyme arthritis?

Medical treatment for Lyme arthritis:

Treatment of Lyme arthritis is based on several small, double-blind, or randomized studies & observational findings. The effectiveness of antibiotics was first demonstrated in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of IM benzathine penicillin, 2.4 million units weekly for 3 weeks versus placebo. In that study, 7 of 20 antibiotic-treated patients (35%) had complete resolution of arthritis, whereas all 20 placebo-treated patients still had arthritis. Subsequently, 11 of 20 patients (55%) managed with IV penicillin, 20 million U daily in 6 divided doses for 10 days, had resolution of arthritis. It was then reported that IV ceftriaxone, 2 g daily, was beneficial in 90% of patients who were given 2-4 weeks of therapy. In an afterward randomized trial, treatment with 1 month of doxycycline, 100 mg twice daily, or amoxicillin, 500 mg four times daily, also led to the resolution of arthritis in 90% of patients.

According to a current suggestion from the Infectious Diseases Society of America,36 patients with Lyme arthritis should be treated starting with a 30-day course of oral doxycycline, 100 mg twice daily, or amoxicillin, 500 mg three times daily. In patients who are unable to take either of these oral drugs, cefuroxime axetil, 500 mg twice daily, might be an acceptable alternative. This medication was shown to be equivalent to treatment with doxycycline or amoxicillin in patients with EM but has not been studied systematically in patients with Lyme arthritis. Unless there are concomitant neurologic abnormalities, oral regimens are the starting treatment of choice as such therapy is safer & more cost-effective.

In our experience, some patients do need longer courses of antibiotic therapy for the effective treatment of Lyme arthritis. Thus, if there is mild residual joint swelling after a 30-day course of oral antibiotic drugs, we repeat the oral antibiotic program for another 30 days. Nevertheless, for patients who continue to have moderate-to-severe joint swelling after a 30-day course of oral antibiotics, we treat them with IV ceftriaxone, 2gm/day. Although there is a trend toward greater efficacy within 4 weeks compared with 2 weeks of antibiotic drugs, there is also a greater frequency of adverse events. Thus, our practice is to prescribe a 4-week course of IV therapy, but to monitor the patient closely & to stop the antibiotic if complications occur.

Even in patients who had minimal or no improvement with oral doxycycline, we significantly observe moderate improvement or even complete resolution of arthritis with IV therapy. Moreover, even in those with persistent joint inflammation, the synovitis tends to change after IV therapy with reduced size of effusions but continued synovial tissue hypertrophy & inflammation. Courses longer than 30 days of IV antibiotics seem not to be beneficial & might be associated with a still greater frequency of adverse effects. Additionally, a recent double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of patients in Europe did not find a benefit of added oral amoxicillin therapy following treatment with IV ceftriaxone. A number of newer oral antibiotics in an FDA-approved drug library, including daptomycin, carbomycin, & cefoperazone, have been shown to have marked efficacy against persisting spirochetes in culture, but it is not yet known whether such antibiotics would be beneficial in patients with Lyme arthritis that is more difficult to treat.

Adjunctive therapy

During treatment, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen or naproxen, might be used for pain. We rarely give oral or intra-articular corticosteroids, & not until antibiotic treatment is completed, since these drugs permit greater growth of spirochetes,& because of the association of intra-articular steroid injections with a longer time period of arthritis in some studies. When joints are inflamed, a decrease in activity is important. If patients are limping, we suggest crutch walking. Children might be more likely to regain normal function within 4 weeks after the initiation of antibiotic treatment, but especially in adults, inflamed joints typically lead to quadriceps atrophy. Therefore, following the completion of antibiotic treatment & resolution of joint inflammation, formal physical therapy, including bicycle riding, is frequently needed.

Therapy for Antibiotic-Refractory Arthritis

The algorithm that we use for the diagnosis & treatment of antibiotic-refractory arthritis If synovitis persists following two or more months of oral antibiotics & one month of IV antibiotics, we employ a similar regimen to that used in the treatment of other forms of chronic inflammatory arthritis, including rheumatoid arthritis & reactive arthritis. The agents used involve NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen or naproxen, & DMARDs, such as hydroxychloroquine or methotrexate, depending on the severity of the arthritis. Although there have been no formal trials with these agents, in practice, they reduce the severity of inflammation & have not resulted in breakthrough cases of active infection. We usually do not give oral or intra-articular injections of corticosteroids, even in the post-antibiotic period, although others have reported clinical utility, particularly in the pediatric population.

In more recent years, with greater experience using more potent DMARD drugs, we have developed an enhanced treatment strategy, now more commonly choosing low-dose methotrexate (MTX), typically 15-20 mg/week, over hydroxychloroquine as the initial DMARD, & reserving hydroxychloroquine, significantly 400mg daily, for cases with milder synovitis. Moreover, in a few patients who had incomplete responses to MTX or in those with contraindications to MTX, we have utilized TNF inhibitors, generally injectable forms such as etanercept or adalimumab. The onset of action of MTX & other DMARD drugs can be slow, but we expect to see significant feedback in 1-3 months. Since antibiotic-refractory arthritis has resolved after a median phase of 9-to-14 months (range, 4 months to 4 years) after the start of antibiotic therapy,12 long courses of DMARD therapy are generally not required. We typically give these medications for only 6-12 months rather than indefinitely as in the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. If the feedback to a DMARD agent is incomplete & if the arthritis is limited to one joint, primarily the knee, arthroscopic synovectomy is an option. By removing most of the inflamed synovial tissue in both the anterior & posterior compartments of the knee, arthritis does not usually recur when synovial tissue grows back.

Physiotherapy treatment for Lyme arthritis:

Early-stage Lyme disease can only be treated with antibiotics & other adjunct medications such as analgesics. Some doctors will refer patients with chronic Lyme disease symptoms that do not react to medication to physical therapy. The role that physical therapy plays in the treatment of Lyme disease primarily to:

- Relieve pain,

- Prepare de-conditioned patients to start a home-based exercise program

- Educate patients regarding proper exercise technique & frequency, duration, & resistance appropriate to achieve wellness

- benefits without exacerbating Lyme-related symptoms.

Physical therapy interventions include:

- Massage,

- Range of motion,

- Myofascial release

- Modalities include ultrasound, moist heat, & paraffin.

Generally, ice packs & electrical stimulation are contraindicated, though there is no research to support this.

Exercise prescription is aimed at improving strength & gradually increasing the patient’s conditioning level which might be severely impaired as a result of chronic Lyme infection. Whole-body workouts generally include extensive stretching, light calisthenics, & light resistance training with low loads and high repetitions.

In addition, many patients with specific neurological complications such as Facial Palsy might also be referred for physical therapy. Electrical stimulation to paralyzed or weak facial muscles following Lyme-related neurological insult is considered a fairly common practice, though the research does not fully support its usage. There are few randomized controlled trials investigating its effectiveness & those that do exist indicate that it might be neither harmful nor beneficial with many therapists taking a conservative approach & waiting several months between symptom onset and initiation of an e-stim program to allow natural neurological recovery to occur. Neuromuscular Facial Reeducation has been indicated to be beneficial in facial palsy, as has EMG biofeedback.

Physical Therapists should be aware of the features of Lyme Arthritis which typically manifests approximately four months after Erythema Migrans. It is most usually in the knee but can be found in multiple joints.

What is the summary of Lyme arthritis?

Arthritis is a late manifestation of Lyme disease, generally beginning months after the tick bite. Nevertheless, a history of erythema migrans or tick bites might be lacking. Patients have intermittent or persistent attacks of joint swelling & pain, primarily in one or a few large joints, often the knee, during a period of months to several years, with few systemic manifestations. The diagnosis is settled by two-tier serologic testing for B. burgdorferi by ELISA & IgG Western blotting, which typically shows strong responses to many spirochetal proteins with many bands present. PCR testing of synovial fluid for B. burgdorferi DNA is frequently positive prior to antibiotic therapy, but the test is not a reliable indicator of spirochetal eradication following antibiotic treatment, since spirochetal DNA might persists after the spirochetal killing.

Initially recommended therapies include a 30-day course of oral doxycycline or amoxicillin. Nevertheless, for patients with persistent joint swelling despite oral therapy, IV ceftriaxone for 2 to 4 weeks might be needed for successful treatment. A small percentage of patients might have persistent arthritis for months or several years after both oral & IV antibiotic therapy, which might be treated successfully with anti-inflammatory agents, DMARDs, or synovectomy. The antibody response to B. burgdorferi declines gradually after treatment, but the test typically remains positive for years after therapy.

After management with antibiotics, in most cases, the disease will go away without leaving any consequences. There are individual cases where definite joint damage has occurred, including a limited range of motion & premature osteoarthritis.

FAQ (frequently asked questions)

About 60% of patients who are infected with Lyme develop arthritis unless they receive antibiotics. In most, Lyme arthritis resolves after 30 days of treatment with oral antibiotic drugs, such as doxycycline or amoxicillin

It is common for patients presenting with arthritic pain in the knee to be misdiagnosed with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Nevertheless, one major difference between Lyme disease & arthritis is that Lyme arthritis frequently manifests in larger joints, & often only on one side of the body in one knee, for example.

Stage 3, or late persistent Lyme disease, can occur months or years after infection. If the disease hasn’t been promptly or effectively treated, the patient might have damage to the joints, nerves, & brain. It is the last & frequently the most serious stage of the disease.

While not classified as an autoimmune disease, research indicates that Lyme disease might trigger an autoimmune response & its symptoms might mimic an autoimmune disease. Lyme disease is caused by the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi & Borrelia mayonii, transmitted through the bite of an infected black-legged tick.

The diagnosis of late-stage Lyme disease can be very difficult & is generally made by a specialist in infectious diseases. The diagnosis can be confirmed if the affected person has had the characteristic ‘bull’s eye’ rash & has lived or worked in areas where ticks are present, or with a blood test.

Rheumatologists are doctors who are experts in diagnosing & treating diseases that can affect joints & muscles, including infections such as Lyme disease.

One Comment