WINGING OF SCAPULA

Table of Contents

What is Winging of the Scapula?

The term ‘winged scapula’ (also scapula alata) is used when the muscles of the scapula are too weak or paralyzed, resulting in a limited ability to stabilize the scapula. As a result, the medial border of the scapula protrudes, like wings. The main reasons for this condition are musculoskeletal- and neurological-related.

Related Anatomy

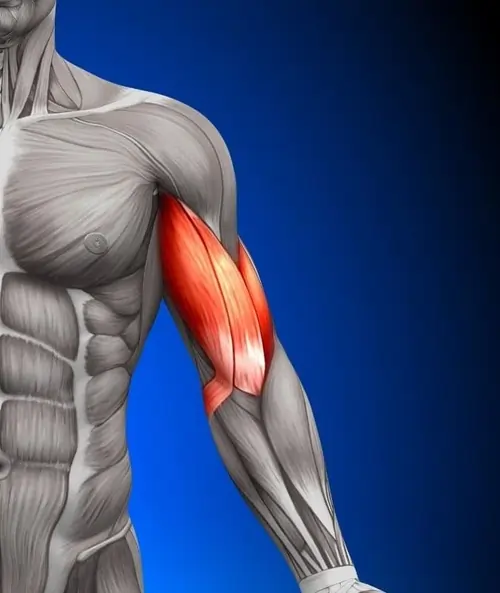

Serratus anterior

Originating from the first nine ribs, the serratus anterior is a wide, flattened sheet of muscle that wraps around the thoracic wall posteriorly and inserts into the costal aspect of the medial border of the scapula. There are three functional components to the serratus anterior. The superior component enters the superior medial angle of the scapula after emerging from the first and second ribs. When the arm is raised overhead, this part acts as the anchor that permits the scapula to rotate. The middle part of the serratus anterior, which serves to protract the scapula, arises from the third, fourth, and fifth ribs and inserts on the scapula’s vertebral border.

The inferior component attaches to the inferior angle of the scapula, originating from the sixth to ninth ribs. The purpose of this third section is to rotate the inferior angle laterally and upward while also protracting the scapula. The serratus anterior’s primary purpose is to protract and rotate the scapula, maintaining it in close proximity to the thoracic wall and maximizing the glenoid’s position for optimal upper limb motion efficiency.

The anterior rami of the fifth, sixth, and seventh cervical nerves give rise to the long thoracic nerve, which innervates the serratus anterior exclusively. Before joining the seventh cervical nerve branch that courses anteriorly to the scalenus medius, branches from the fifth and sixth cervical nerves run anteriorly via the scalenus medius muscle. After passing over the first rib, the long thoracic nerve descends deeply to the brachial plexus and the clavicle.

The nerve innervates the serratus anterior muscle after passing through a fascial sheath and continuing down the lateral portion of the thoracic wall. With an average length of 24 cm, it is believed that the nerve’s lengthy and twisting path leaves it vulnerable to mechanical harm.

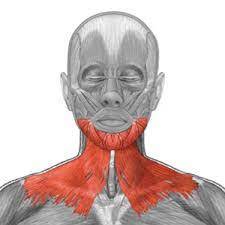

Similar to the serratus anterior, the trapezius muscle is used to rotate, retract, and raise the scapula. The first cervical vertebra to the twelfth thoracic vertebra’s spinous processes are the source of the muscle. The scapula’s spine is where the main insertion is located. It may be divided into three parts: the inferior part turns the inferior angle laterally, the middle piece adducts and retracts, and the superior portion raises the scapula and rotates the lateral angle upward.

The spinal accessory nerve, also known as cranial nerve XI, is the only nerve that innervates the trapezius. It passes superficially across the posterior cervical triangle before descending vertically down the trapezius’s deep surface.

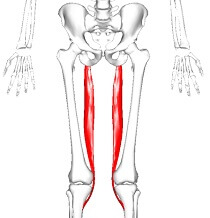

Rhomboids

Together, the two rhomboid muscles rotate the scapula’s lateral border downward and retract and raise it, just deep to the trapezius. The ligamentum nuchae of the neck and the spinous processes of the seventh cervical and first thoracic vertebrae are the origins of the smaller rhomboid minor, a cylindrical muscle. At the base of the scapular spine, it extends laterally and downward to the medial edge of the scapula. From the insertion of the rhomboid minor to the inferior angle of the scapula, the bigger and more inferior rhomboid major inserts on the medial edge of the scapula. It originates from the spinous processes of the second through fifth thoracic vertebrae.

The dorsal scapular nerve innervates both rhomboid muscles. Its fibres are mostly generated from the C5 nerve root, with smaller contributions from the C4 or C6 nerve roots. The dorsal scapular nerve passes via the scalenus medius muscle and then travels to the levator scapulae, where it provides innervating fibres to the muscle, just like some of the fibres of the long thoracic nerve do. After passing through or piercing the levator scapulae muscle, the nerve may then go beneath the brachial plexus and emerge at the anterior surface of the rhomboid muscles.

What causes the winging of the scapula?

INJURIES:

A variety of injuries can damage important nerves and muscles, leading to a winged scapula.

- Traumatic injuries: Blunt trauma to the nerves that control the muscles of your neck, upper back, and shoulder can lead to scapular winging. Examples of blunt trauma include dislocating your shoulder or twisting your neck in an unusual way.

2. Repetitive motion injuries: Repetitive movements can also cause injuries. This type of injury is common among athletes, but it can also be caused by everyday tasks, such as:

-washing the car

-digging

-trimming hedges

-using your arms to prop your head up while lying down

-Nontraumatic injuries

-Nontraumatic injuries aren’t caused by physical force. Instead, they can be caused by surgery.

Rib resections, mastectomies, and procedures that require general anesthesia may cause nerve damage.

Epidemiology

Very rarely does serratus anterior palsy result in a winged scapula. FARDIN et al. reported that of 7,000 patients evaluated in the electromyographical laboratory, 15 instances or so were reported as occurring. Out of 38,500 patients seen at the Mayo Clinic, just one instance was reported in another publication (Overpeck and Ghormley). Three diagnoses of serratus anterior paralysis were made over a series of 12,000 neurological exams in another investigation.

Symptoms

Type 1:

A visible angulus inferior and a pronounced anterior tilt of the scapula can be observed.

The causes for this type are shortening of the M.pectoralis minor, shortening of the posterior joint capsule, and muscular unbalance of the Muscle Trapezius pars ascendens and the Muscle serratus anterior.

Type 2:

A visible margo medialis and an intern rotation of the scapula can be observed.

The causes are: shortening of the posterior joint capsule, shortening of the Muscle latissimus dorsi and muscular unbalance of the M.trapezius and the M.serratus anterior.

Differential Diagnosis

- Rotator Cuff Disorders

- Frozen Shoulder

- Over-stressed Trapezius

- Glenohumeral Instability

- Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

- Cervical Spondylosis

- Acromioclavicular Disorder

Diagnosis

A practitioner can diagnose scapular winging after conducting a thorough history and physical examination.

The underlying neuromuscular pathology can be determined with the use of electrodiagnostic testing.

Establishing the muscular disease and its neurologic origins can be done with neuromuscular ultrasonography.

Treatment:

As of right now, there is no recommended course of action for treating scapular winging initially. Pain management and physical therapy are the suggested first treatments, as was previously described. Patients may experience further problems such as adhesive capsulitis (also known as frozen shoulder), subacromial impingement, and other brachial plexus-related pathologies if therapy is not started early.

Medical Treatment

Sometimes, within two years, cases of scapular winging caused by injury to the serratus anterior nerve resolve on their own. Early in your recovery, your doctor could also advise using a brace for a few months or suggesting physical therapy and exercise.

Your doctor will likely advise a combination of physical therapy and exercise treatment for scapular winging caused by injury to the dorsal scapular nerve. In addition, they could recommend muscle relaxants, analgesics, anti-inflammatory medications, or a mix of the three. During recovery, supports like braces and slings might be beneficial as well.

Surgical Treatment

There are surgical procedures where the outcome has left the patient quite happy. However, other research favour non-operative care, particularly for elderly individuals who have little symptoms and are inactive.

These treatments are:

• Split pectoralis major transfer.

• Modified version of the Eden-Lange procedure.

• Scapuloplexy.

Physiotherapy Treatment:

Physiotherapy treatment is mainly improving muscle strengthening exercises of weak or Paralyzed muscles and stretching of tight muscles with also symptomatic pain relieving modalities if pain persists with winging of scapulae.

Electrical Stimulation of the affected muscle

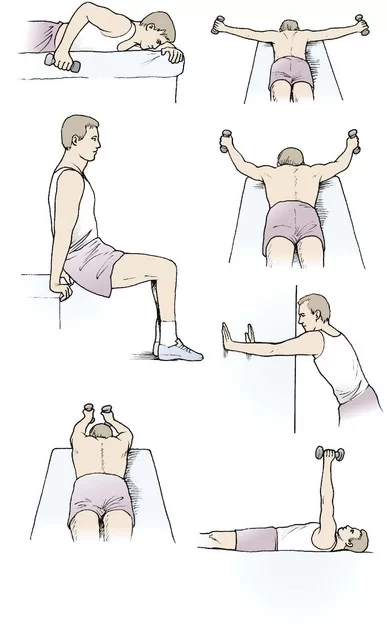

Exercise for winging of the scapula:

The following exercises are helpful for the strengthening of weak scapular muscles.

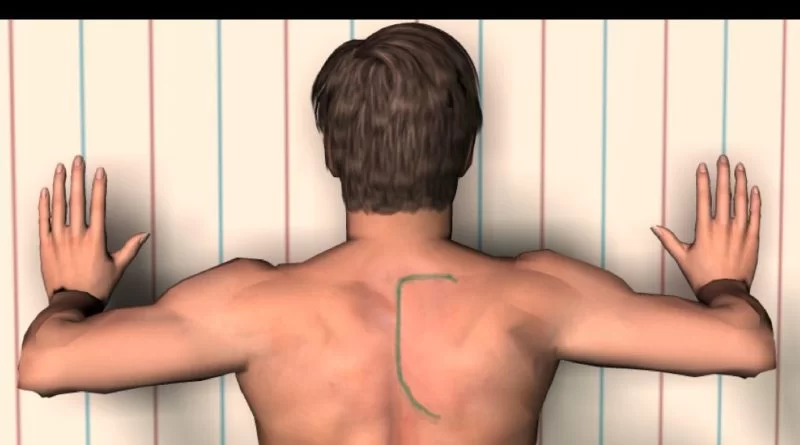

Muscle activation of scapular muscle:

-Correct the scapular position with tactile feedback and ask the patient to move the scapula downward and inward.

-scapulothoracal feedback of muscle control.

-the patient put his fingers on the processus coracoideus, after this the patient move his scapula backward with his fingers on processus coracoideus.

Dynamic scapulothoracic muscle training:

-push up with plus

-elevation in scapular flat

-elbow push-ups

-press up

-low rowing

-horizontal abduction

-retroflection against resistance

-serratus punch upright and prone

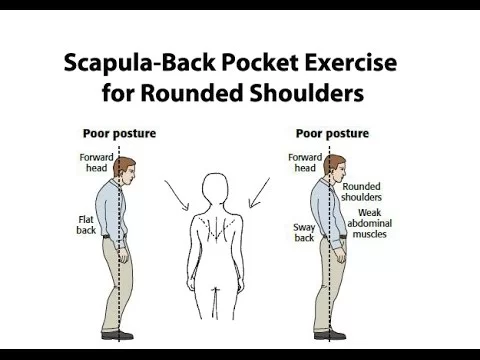

Elbow in the back pocket exercise:

Dynamic hug Exercise:

PREVENTION:

- avoiding repetitive shoulder or arm movements when possible

2. maintaining correct posture

3. using an ergonomic chair or pillow

4. Use shoulder-friendly ergonomic bags and backpacks

5. avoiding carrying too much weight on your shoulders

6. stretching and strengthening the muscles in your neck, shoulders, and upper arms.

Scapular winging recovery

Depending on the underlying reason, course of therapy, and affected nerves and muscles, recovery from scapular winging might take several months to years. While surgical surgery will probably take many months to show effects, nonsurgical treatment methods can begin to work nearly immediately.

Even though scapular winging is typically reversible, in certain situations, you may develop a persistent reduction in range of motion. Consult your physician as soon as you begin having symptoms in order to increase the likelihood that you will fully recover.

Conclusion

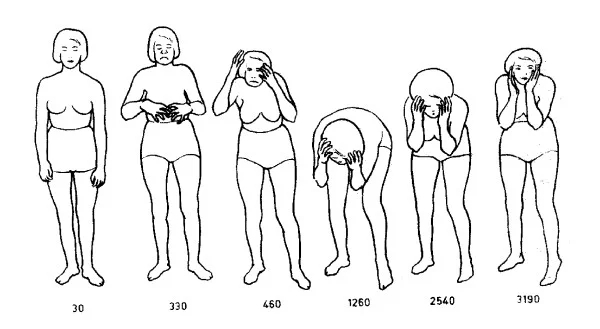

Scapular winging is an uncommon yet crippling disorder that reduces upper limb functional activity. Although scapular winging may be easily detected by visual inspection of the scapula, its cause is frequently more mysterious. When patients are instructed to push up against a wall by extending their arms horizontally and forward, it highlights their medial winging, which is a result of serratus anterior paralysis.

On the other hand, during vigorous abduction, lateral winging increases in cases with trapezius paralysis. The modest lateral winging associated with rhomboid paralysis can be made more noticeable by extending the arm from its completely flexed posture. For an accurate diagnosis, an electromyography examination of all scapulothoracic muscles is necessary. Treatment for scapular winging should start slowly to give the condition time to heal on its own.

In cases of trapezius paralysis, early spinal accessory nerve exploration is necessary, and decompression of the dorsal scapular nerve may be recommended following the failure of conservative therapy. Treatment for serratus anterior paralysis should be cautious for at least six months, but ideally up to twenty-four months, after which it is doubtful that more recovery will occur with conservative measures. Exercises to preserve a range of motion (ROM) are crucial to prevent periscapular muscular contracture, but extreme caution must be used to avoid stretching the paralyzed muscle. Exercises for strengthening should be added gradually and only when the muscle has clearly begun to regenerate its innervation.

Dynamic muscle transfer effectively addresses chronic scapular winging caused by muscular palsies in the serratus anterior and trapezius, resulting in winging resolution ranging from good to outstanding and scapulothoracic rhythm recovery.

FAQs

The most frequent cause of a winged scapula is often injury or compromised serratus anterior muscular innervation. The long thoracic nerve is the nerve that innervates this muscle.

Due to unopposed muscular activity of the other functional scapular muscles, the scapula may translate medially or laterally along the posterior thoracic wall. This difference is referred to as medial (serratus anterior paralysis) or lateral (trapezius or rhomboid paralysis) winging.

To fix scapular winging following exercise may helpful:

Scapular Pushup: Simply retract and protract your scapula for each repetition while maintaining a straight torso for each pushup.

Rear Dumbbell Flye.

Rope Pulldown.

Single Straight-Arm Cable Pulldown.

Disruption of scapulohumeral rhythm by scapular winging has been reported to result in a reduction in upper extremity flexion and abduction, power loss, and significant discomfort. In early children, a winged scapula is considered a typical posture; in older children and adults, it is not.

A typical cause of winging of the scapula is paralysis of the serratus anterior muscle (SAM), which results from damage to the long thoracic nerve (LTN) or its nerve roots.

A winged scapula can result from poor posture and muscular imbalances, such as a weak serratus anterior muscle. This is an additional reason why, if you spend most of your day at a desk, it’s critical to make sure your workspace is ergonomically sound.

References

- Martin, R. M., & Fish, D. E. (2008). Scapular winging: Anatomical review, diagnosis, and treatments. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 1(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-007-9000-5

- Scapular Winging. (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Scapular_Winging

6 Comments