Oligoarthritis

Table of Contents

What is oligoarthritis?

In Latin, “oligo” means “few.” If you have oligoarthritis, you have fewer than five joints affected by arthritis.

Oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis formerly called pauciarthritis or pauciarticular-onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis is defined as juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) including fewer than five joints. It is the most common subgroup, constituting approximately 50 % of cases of JIA. This subgroup of JIA is further classified into persistent oligoarthritis, in which there is no additional joint involvement after the first six months of illness, & extended oligoarthritis, in which there is the involvement of additional joints after the first six months such that more than four joints are ultimately affected. Approximately 50 & of children with the oligoarticular disease go on to have extended oligoarticular disease.

The condition causes joint inflammation, stiffness, & pain in large joints of your body, specifically the knees, ankles, and elbows, & the middle layer of the eye (uvea).

Oligoarthritis affects about two-thirds of children & young people with arthritis and most commonly affects one or both knees.

Children with oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (oligoarticular JIA) have arthritis in fewer than 5 joints in the first 6 months of the disease. In some children, more joints become included over time. Problems with the eyes & bone growth also can happen.

Treatments can help with symptoms, so children can live full and active life. The symptoms can go away for a time being called remission. In some kids, the disease goes away permanently.

Oligoarthritis is defined as arthritis affecting two to four joints during the first six months of the disease.

This form of arthritis is frequently mild and is the most likely to go away and leave little or no damage to your joints.

This kind of arthritis has the highest chance of you developing chronic anterior uveitis (inflammation of the eye), so you’ll require regular eye checks with an ophthalmologist (eye specialist). This eye inflammation doesn’t cause a red or painful eye but still can cause decreased vision if it isn’t treated. This is why regular checks are important.

What are the signs and symptoms of oligoarthritis?

Oligoarticular JIA affects females more frequently than males, as does polyarticular disease. The peak incidence of oligoarticular JIA is in the second & third years of life. It is less common over five years of age and rarely starts after age 10 years.

The typical case with oligoarticular JIA is a toddler girl who is noticed to be limping without any complaint. Frequently, the caregiver notices that the child “walks funny” in the morning, but after a little time seems fine. In many cases, the child has never complained of pain; the caregiver needs medical advice only because the knee is swollen. It is unusual for the caregiver to be able to say specifically exactly when the illness started.

Oligoarticular JIA affects the large joints typically knees & ankles, sometimes also wrists and elbows, but rarely the hips. Systemic manifestations (other than uveitis) are characteristically not present. Thus, fever, rash, or other constitutional symptoms advocate a different diagnosis.

The involved joints in children with oligoarticular JIA are typically swollen & tender. Involved joints are generally warm, but erythema is characteristically absent. Young children usually have a much greater range of motion than adults. As a result, the limitation of motion might not be recognized unless the involved joint is compared with the opposite side.

Several long-term complications may occur in oligoarticular JIA. The most often & significant complications are uveitis & leg-length discrepancy.

After the first 6 months of illness:

Some kids don’t get arthritis in other joints. This is called persistent oligoarthritis.

Some kids do get arthritis in more joints. This is called extended oligoarthritis.

Other problems that can happen include:

- uveitis (inflammation inside the eye)

- problems with jaw expansion if arthritis is in the jaw joint

- if arthritis is in the knee, leg length discrepancy is present (one leg is longer than the other)

- short stature is being shorter than other kids the same age

Oligoarticular JIA is an autoimmune illness. This means that the human immune system, which usually attacks germs, mistakenly attacks the joints. This causes inflammation swelling & irritation in the joints & other problems.

The condition usually initiates when a child is 2–3 years old. It is more common in girls.

In some cases, oligoarthritis can spread to other joints in the patient’s body over time. Each case is unique to the patient diagnosed with the condition. Not every case of oligoarthritis spreads to other joints, & the condition can range from mild to severe.

What are the causes of oligoarthritis?

Oligoarthritis is a kind of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The phrase “idiopathic” refers to an unknown cause. Some studies advocate that the condition results from a genetic mutation activated by a virus or bacteria, but research is ongoing.

Doctors don’t know exactly why kids & teens get JIA.” It can run in families but often does not. It’s likely because of a merger of:

- genetic (inherited) causes

- the way the immune system reacts to infection & illness

- a trigger, such as an infection

What are the types of oligoarthritis?

There are two types of oligoarthritis based on how many joints are involved over a period of time:

- Persistent oligoarthritis: Four or fewer joints affected with arthritis after 6 months.

- Extended oligoarthritis: More than four joints are affected with arthritis after 6 months.

What are the complications of oligoarthritis?

The most common complications associated with oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis are temporomandibular joint (TMJ) arthritis, uveitis, leg-length discrepancy, and short stature.

Temporomandibular joint arthritis – Arthritis of the TMJ is present in greater than 75 percent of children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The clinical importance of these findings is not clear since not all children go on to develop micrognathia & condylar alterations can improve in some children. Clinical findings that might indicate temporal mandibular joint involvement include crepitus, pain with TMJ motion, limited maximal incisal opening, & limited forward movement of the mandibular condyle (limited translation) with mouth opening. TMJ arthritis, nevertheless, can also be asymptomatic.

TMJ arthritis is concerning in children who are actively growing since the mandibular growth plate is situated in close proximity to the fibrocartilage of the joint. Damage to this growth plate from uncontrolled inflammation might lead to jaw undergrowth or micrognathia. Patients are examined for this complication by physical examination, with imaging performed if there are concerning findings on the exam.

TMJ arthritis can be healed with intraarticular joint injections (typically performed by interventional radiologists) with or without starting systemic therapy. If significant micrognathia develops, surgical correction is an option once the facial bones are completely developed.

Uveitis – The most serious complication of oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, occurring in approximately 20 to 25 percent of children, is the development of uveitis or iridocyclitis (inflammation of the anterior uveal tract and the adjacent ciliary body). The uveitis is significantly isolated to the anterior chamber & is completely asymptomatic. A periodic slit-lamp ophthalmic examination is needed for screening and detection.

The serologic marker most strongly related to uveitis is antinuclear antibodies (ANA). Thus, children who are ANA positive are screened more frequently than those who are ANA negative. Diagnosis at a younger age (less than six years) increases the risk of uveitis.

Screening — The sections on ophthalmology and rheumatology of the American Academy of Pediatrics developed a schedule for ophthalmologic examination based on the age of onset, juvenile idiopathic arthritis category, duration of disease, and the presence of ANA. These guidelines were modified in 2007 for application to the juvenile idiopathic arthritis classification criteria. The 2019 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) or Arthritis Foundation guidelines suggest a simplified approach of ophthalmologic screening every 3 months for all children and adolescents at high risk of uveitis. This involves patients with oligoarticular, polyarticular (rheumatoid factor [RF] negative), psoriatic, or undifferentiated juvenile idiopathic arthritis who are also ANA positive and had disease onset at <7 years of age and have disease duration of ≤4 years. Screening every 6 to 12 months is advocated for all other patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

The rationale for frequent screening examinations is to minimize the risk of ocular complications due to late diagnosis and treatment of uveitis in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. As an example, approximately one-third of patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis and uveitis (53 of 142) in a Canadian study developed ocular complications. The most common sequelae were cataracts (n = 33) and synechiae (n = 31), followed by glaucoma (n = 22), band keratopathy (n = 20), and macular edema (n = 7). After a mean follow-up time of 6.9 years, 10 patients developed legal blindness in 10 eyes, and 4 patients developed an impaired vision in 6 eyes. The importance of appropriate screening must be emphasized to caregivers if the frequency of complications is to be reduced.

Treatment – Uveitis is initially treated with topical corticosteroids. According to the Single Hub and Access Point for Pediatric Rheumatology in Europe (SHARE) recommendations, systemic immunosuppression should be started if uveitis is still active after three months or reactivation occurs with tapering of topical corticosteroids. Methotrexate is the first-line steroid-sparing agent for chronic uveitis. Anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha monoclonal antibodies, specifically adalimumab, infliximab, or golimumab, are typically added if the inflammatory process does not abate or are involved as part of initial systemic therapy in patients with severe active uveitis and sight-threatening complications because of uveitis or topical corticosteroid treatment. Another option is systemic glucocorticoids. There are case reports of successful utilization of cyclosporine, rituximab, abatacept, tocilizumab, or golimumab (another TNF inhibitor) in especially severe, treatment-resistant diseases. Mycophenolate mofetil may be beneficial in children who have not responded to these therapies. Etanercept, nevertheless, does not seem to benefit ocular inflammation.

Topical corticosteroids, significantly prednisolone acetate 1% or dexamethasone 0.1%, are the first line of treatment for juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis. Topical corticosteroids were first shown to be effective for uveitis in a randomized trial published in 1979. The frequency of drops varies greatly (hourly to daily) depending on the severity of inflammation. Adverse effects of ophthalmic corticosteroids that are done with chronic use include increased intraocular pressure and cataracts. Cycloplegic topical drops usually muscarinic receptor blockers are generally also used to help treat synechiae. Systemic therapy is utilized if inflammation is not adequately controlled or the patient is unable to wean off of topical therapy. For severe, vision-threatening inflammation, systemic therapy can be utilized as a part of initial therapy.

Methotrexate is typically the first corticosteroid-sparing agent used in the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis. In a retrospective study of 38 children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis, 25 received methotrexate (subcutaneous or oral) at a mean dose of 15 mg/m2. Of these 25 patients, one discontinued therapy because of intolerance, and four had an inadequate response and required escalation of therapy. In the 20 methotrexate responders, remission happened at a mean of 4 months after initiation. In another study of 35 children, 17 attained inactive uveitis on methotrexate with or without the rise of topical corticosteroid therapy. Eight achieved inactive disease with systemic glucocorticoids, seven needed additional immunosuppression for adequate control, & three had active inflammation at the end of the study.

The anti-TNF biologic agents, infliximab, adalimumab, & golimumab, are options for uveitis not adequately controlled with topical corticosteroids & methotrexate. In a retrospective, multicenter study of children with noninfectious uveitis, 56 children (half with JIA) with active uveitis in spite of therapy with glucocorticoids & other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs; methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine) were treated with an anti-TNF agent (infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept).

In one trial, 90 children with active uveitis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis (mostly oligoarticular) on a stable dose of methotrexate were continued on their current therapy and also randomly assigned to adalimumab, administered subcutaneously every two weeks or placebo for 18 months or until treatment failure, based upon a multicomponent intraocular inflammation score. Treatment failure was observed in 16 of 60 patients on adalimumab compared with 18 of 30 in the placebo group, with a typical delay in time to treatment failure in the adalimumab group. In addition, more patients in the adalimumab group compared with placebo were able to taper or discontinue topical corticosteroids, & they also had a longer mean time period of the sustained inactive disease (no cells seen on the slit-lamp exam). Nevertheless, side effects, including serious adverse events, were more usual in the adalimumab group. The trial was stopped early, which can cause an overestimation of the treatment effect. Although the trial enrolled patients with more severe diseases, limiting the generalizability of the results, the beneficial effect on less severe cases may be even greater. The efficacy of adalimumab monotherapy was not evaluated nor was the ability to taper other medications.

Monitoring – Once uveitis is diagnosed, the frequency of subsequent examinations is based on the response to therapy, changes in therapy, and the presence of complications.

Ocular complications – Approximately one-third to one-half of patients with uveitis will have ocular complications, highlighting the importance of often screening & aggressive therapy. A retrospective review of patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis and uveitis from a single, Canadian tertiary center reported complications in 53 of the 142 patients with uveitis. The most common complications were cataracts and synechiae, followed by glaucoma, band keratopathy, and macular edema. After a mean follow-up time of 6.9 years, 10 patients had legal blindness in 10 eyes, & 4 patients developed an impaired vision in 6 eyes. Another retrospective review found that the male sex was a risk factor for a more complicated course of uveitis & poorer visual outcomes. Nevertheless, severe disease is also seen in females.

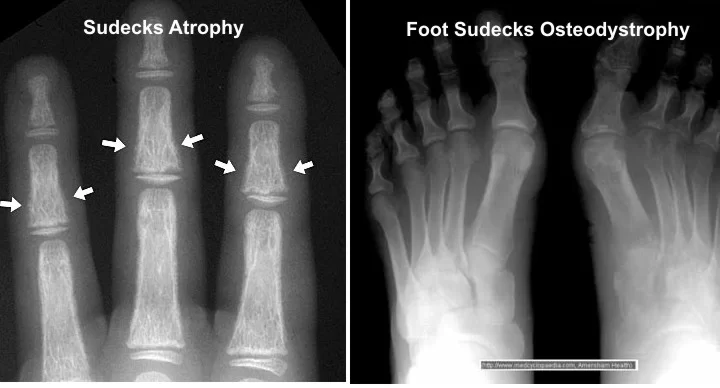

Leg-length discrepancy-The leg-length discrepancy is the second common complication of oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. There can be significant asymmetric bony overgrowth in both length & width when a single knee joint is involved, resulting in a leg-length discrepancy over time.

Joint injection with glucocorticoids early in the course of oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis may prevent leg-length discrepancies. A retrospective study compared the development of leg overgrowth among a cohort of children with oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis who received intraarticular glucocorticoids with a similar group of patients followed at a different center who did not receive such injections. Although not a randomized trial, both groups have had similar clinical characteristics. None of those who received glucocorticoid injections of the knee or ankle developed a significant leg-length discrepancy or needed a lift. By comparison, among those who did not have injections, 50 % had leg-length discrepancies, averaging approximately 1 % of total leg length.

Leg-length discrepancies of less than 1 cm are not clinically significant & are present in up to 70 percent of the population. When they become greater, they are associated with gait abnormalities and increased strain on the shorter leg. Proper gait can be kept in children with mild leg-length discrepancies (1 to 2 cm) by placing an appropriate lift in the opposite shoe. An absolute discrepancy of great than 2 to 2.5 cm should prompt orthopedic assessment for possible surgical management. Orthopedic consultation should be acquired before the child reaches skeletal maturity. By using radiographic standards to forecast the remaining growth, it is possible to surgically close the distal tibial epiphysis in the leg that is longer & allow catch-up growth on the opposite side. This is a minor surgical procedure (stapling) that generally has a good outcome. Similar discrepancies of bone growth might occur in other affected joints, but the knee is most common since two-thirds of longitudinal growth occurs around this joint.

Short stature – Growth retardation with short stature is seen in 11 to 36 % of patients with persistent oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. In one series, severe growth retardation was more likely in children who needed treatment with DMARDs than those who were treated with intraarticular glucocorticoid injections alone. This difference is most likely due to the latter group having milder disease, rather than any effect of the drugs. Risk factors for growth retardation involved younger age at onset & elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).

Amyloidosis – Although the risk of developing secondary (AA) amyloidosis is generally small in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis, there may be an increased risk in those with the extended oligoarticular disease. In one study of 215 children with various subtypes of juvenile idiopathic arthritis, only three (1.4 percent) developed amyloidosis, but two of these three had the extended type of oligoarthritis. Nonetheless, amyloidosis is sufficiently rare that most practicing pediatric rheumatologists report never having seen secondary amyloidosis.

What is the prevalence of oligoarthritis?

Oligoarthritis is the most popular kind of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). An estimated 4 to 16 in 10,000 children have JIA in North America & Europe. Approx half of all children with JIA have oligoarthritis. Up to 20% of patients diagnosed with oligoarthritis also have uveitis eye inflammation.

Whom oligoarthritis affects mainly is a big question. Oligoarthritis is a juvenile condition that affects children and teenagers. It more commonly affects children assigned to females at birth, but anyone can get the condition.

What is the differential diagnosis of oligoarthritis?

The differential diagnosis of oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis principally includes the other subtypes of juvenile idiopathic arthritis, particularly polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriatic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, & spondyloarthritis (enthesitis-related JIA). There should not be any systemic complications of oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis other than uveitis. If there is evidence of systemic illness, the diagnosis of oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis is in doubt, and a complete investigation to exclude malignancy, infection (particularly Lyme disease in endemic areas), or other diseases should be undertaken.

Polyarticular JIA – In children less than 10 years of age, polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis often begins similarly to oligoarticular disease, with one or two joints affected. Antinuclear antibody (ANA) is frequently positive on presentation in this age group. Polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis involves five or more joints during the first six months after disease onset. In addition, joint inclusion is symmetric, & an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), anemia, and hypergammaglobulinemia may be present.

Psoriatic JIA – Dactylitis is a swollen finger or toe, sometimes referred to as a sausage digit might be present in a child with fewer than five inflamed joints, but it is more typical of psoriatic arthritis, a distinct category of juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Spondyloarthritis/enthesitis-related arthritis (ERA) – Children more than six years of age with arthritis involving large joints (hips or knees) & enthesopathy (pain at the insertions of muscle tendons into bones) also do not have oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rather, these demonstrations are indicative of ERA (spondyloarthritis). Spondyloarthritis is an umbrella term for children with arthritis & varying degrees of enthesitis (inflammation where the tendons attach to the bone). Most children with spondyloarthritis are divided as having ERA, psoriatic arthritis, or undifferentiated arthritis.

Lyme disease – Oligoarticular arthritis is one of the most usual late manifestations of Lyme disease, a tickborne illness. The knee is the most commonly involved joint, but almost any joint can be affected. Typically, the large joints are preferentially affected, & fewer than five joints in total are involved. The knee effusion is characteristically quite big. Unlike other infectious arthritides, Lyme arthritis is not generally very painful. Diagnosis is based on serologic testing with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for screening & a Western blot for confirmatory testing.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) – Elevated inflammatory markers, anemia, history of loose stools or diarrhea, poor weight gain, & family history of IBD in a child with the oligoarticular disease should raise suspicion for IBD. One-third of children with IBD develop arthritis, & arthritis may precede the onset of gastrointestinal symptoms by months to years.

Pigmented villonodular synovitis – Episodic swelling of a single joint should raise doubt about pigmented villonodular synovitis, which is inflammation & overgrowth of the synovium. It most often occurs in large joints and is more common in males than females. Patients present with joint swelling and pain. The synovial fluid is often bloody. Pigmented villonodular synovitis can be distinguished from inflammatory arthritis by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Malignancy – Neoplastic diseases might present with musculoskeletal pain but are an infrequent cause of monoarticular pain in childhood. Both acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) & neuroblastoma may present with joint pain in the same age group as oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. In general, these children are in more severe pain & sicker in appearance. In addition, these entities are associated with marked periarticular pain, which is not present in oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The presence of night sweats or monoarticular hip inclusion should also raise suspicion for malignancy.

Anemia or marked elevation of the ESR is unusual in oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis but is often present in children with malignancies. Additionally, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, anemia, increased lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), & elevated uric acid should raise suspicion for malignancy. Except for neoplastic cells in the peripheral smear, no single laboratory test might be relied upon for differentiating malignancy from juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

The radiologic evaluation might reveal bony metastases in neuroblastoma or metaphyseal rarefaction (“leukemic lines”) in ALL.

Other inflammatory and/or infectious disorders – Children with plant thorn synovitis, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, or tuberculosis are sometimes mistakenly diagnosed with oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. These conditions might be associated with elevated acute phase reactants, acute onset of moderate-to-severe pain, erythema of the overlying skin, or fever that should alert the clinician to see for a diagnosis other than oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Initial symptoms in the hip should be regarded with great concern since oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis rarely begins in the hip joint. Most such patients have different diagnoses. As an example, toxic synovitis is a transient condition that might affects the hip in young children. Other disorders to consider involve Legg Calve Perthes disease, osteoid osteoma, neoplasm, or infectious diseases. In older children, ERA (spondyloarthropathy) & slipped capital femoral epiphysis might also cause symptoms beginning in the hip.

What is the diagnostic procedure for oligoarthritis?

The diagnosis of oligoarticular JIA is made in the presence of arthritis in four or fewer joints during the first six months of the disease after ruling out other causes. The onset of arthritis is usually established from history.

The child’s healthcare provider will diagnose oligoarthritis after performing a complete medical history, which includes learning about their symptoms, the duration, & severity of the symptoms, understanding their medical history, and performing a physical exam on the involved joints. A physician’s exam focuses on ruling out conditions with similar symptoms leading to the child’s diagnosis.

ask whether other family members have had similar problems or any kind of symptoms.

To confirm the diagnosis, the physician may order imaging tests like an X-ray or an MRI to see the affected joints. They might also order a laboratory test like urine, blood, or joint fluid test to determine what is causing the child’s symptoms.

If symptoms affect a child’s vision, a physician will recommend they see an ophthalmologist for an eye exam to check for inflammation of the eye (uveitis).

See for anemia or other blood problems,

inflammation in the body,

and markers for some types of arthritis or autoimmune illnesses

Sometimes, an orthopedic surgeon takes samples of joint fluid or synovium (the lining of the joints). Then the sample is addressed to a lab for testing.

There are not any diagnostic laboratory tests for oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) are often present and are associated with an increased risk of iridocyclitis/uveitis.

Laboratory abnormalities other than ANAs are typically absent, including rheumatoid factor (RF) and antibodies to double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (dsDNA), Sjögren-syndrome-related antigen A (SSA or Ro), Sjögren-syndrome-related antigen B (SSB or La), Smith (Sm), and ribonucleoprotein (RNP). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is usually normal or mildly elevated. The presence of anemia, an elevated ESR or C-reactive protein (CRP), or two or more affected joints at presentation is associated with an increased risk of progression to extended oligoarthritis or polyarticular disease.

Children with oligoarticular arthritis but an otherwise unexplained elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR; >40 mm/hour) or anemia (hemoglobin <11.0 g/dL) fulfill the International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) criteria for a diagnosis of oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. However, this subgroup is far more likely to have the recurrent disease and ultimately evolve into extended oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis with widespread joint involvement. Particular attention should be paid to children within this subgroup since their course, prognosis, & optimal therapy appear to differ from typical oligoarticular JIA.

How can someone prevent oligoarthritis?

Since the cause of oligoarthritis is not known, there’s no way to prevent the condition.

What is the treatment plan for oligoarthritis?

Oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis is treated by a care team that includes:

- a rheumatologist for complications with joints & connective tissue

- a primary care doctor such as a pediatrician or family physician doctor

- a physical therapist

- an ophthalmologist (eye doctor)

Treatment aims are to relieve pain & inflammation, improve strength & flexibility, and prevent joint damage. Treatment usually involves medicines to ease inflammation (taken by mouth & injected into the joint), eye drops for uveitis, physical therapy, and exercise.

Sometimes surgery is required for damaged joints.

Medical treatment for oligoarthritis:

Oligoarticular JIA is generally responsive to intraarticular glucocorticoids. Methotrexate & other immunosuppressive drugs are recommended for children with disease that extends to include five or more joints or require repeat injections. Biologic agents are significantly reserved for patients with uveitis & are also utilized in some patients with extended oligoarticular JIA.

The approach to the treatment of oligoarticular JIA is reviewed here & is consistent with the approach outlined in the 2011 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Juvenile Arthritis Treatment Recommendations. The choice of treatment depends upon disease activity & whether features of poor prognosis are present.

Determining disease activity — Disease activity should be determined before the starting of therapy & periodically thereafter at the decision branch points discussed below:

Low disease activity is defined by the 2011 ACR Juvenile Arthritis Treatment Recommendations as meeting all of the below criteria: ≤1 active joint, normal inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR] / C-reactive protein [CRP]), physician global disease activity assessment of <3 (0 to 10 scale), & patient and a parent or caregiver global assessment of overall well-being of less than <2 (0 to 10 scale).

High disease activity is explained as meeting at least three of the following criteria: ≥2 active joints, inflammatory markers more than twice the upper limit of normal, physician global disease activity assessment ≥7 (0 to 10 scale), & patient and parent/caregiver overall well-being assessment ≥4 (0 to 10 scale).

Moderate disease activity does not satisfy the criteria for low or high disease activity.

Prognostic markers — Patients should also be assessed for the presence of features associated with poor prognosis prior to starting treatment and periodically thereafter at the decision branch points discussed below.

If at least one of the below features is present, the patient is considered to have a poor prognosis:

Hip or cervical spine arthritis

Ankle or wrist arthritis and marked or prolonged elevation of ESR or CRP

Radiographic evidence of joint damage

Initial therapy

There are several options for initial therapy in patients with low disease activity, no poor prognosis risk factors, & no joint contractures, involving intraarticular glucocorticoid injection, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or combination therapy. Intraarticular injection of a joint or joints with long-acting glucocorticoids typically gives relief of symptoms within days. Treatment with NSAID monotherapy is the second option for these patients. NSAIDs generally start to relieve symptoms within two weeks. In patients who respond, NSAIDs are continued until there has been a minimum of 6 months of disease inactivity. A different NSAID can be tried if no result is seen within the first two weeks of therapy, or, alternatively, the patient can be treated with glucocorticoid injection. Patients who do not react to NSAID therapy within a few weeks should be treated with glucocorticoid injection of the affected joint. Infectious etiologies (including tuberculosis) must be excluded before injecting glucocorticoids. Patients who have persistent symptoms despite treatment with NSAIDs & intraarticular glucocorticoids should be treated with methotrexate.

The first-line approach for patients with moderate-to-high disease activity is intraarticular glucocorticoid injection, with NSAIDs as required. Methotrexate, a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD), is also part of initial therapy in patients with high disease activity & risk factors for poor prognosis. Whether methotrexate should be utilized in patients with moderate disease activity was examined in a randomized, open-label trial of children with oligoarticular JIA & at least two swollen joints or one swollen joint (shoulder, elbow, wrist, ankle, or knee) if injected with glucocorticoid in the prior twelve months. There was no significant distinction in the proportion of children who achieved inactive disease or clinical remission by the Wallace criteria & the clinical Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score at 12 months between those patients who underwent glucocorticoid injections alone versus glucocorticoid injections plus oral methotrexate. There was, nevertheless, a significantly increased time to flare in those treated with glucocorticoid injections plus oral methotrexate compared with those treated with injections alone. The addition of methotrexate was not protective against the development of new-onset uveitis. Further research is required to determine whether methotrexate should be used in patients with moderate disease activity. The use of methotrexate in patients with JIA is discussed in greater detail individually.

Several NSAIDs have been approved for use in children with JIA, involving naproxen, meloxicam, celecoxib, & ibuprofen. Many other NSAIDs are routinely utilized by pediatric rheumatologists but have not been specifically approved for use in children. Concerns regarding potential adverse effects, especially cardiovascular events that might not appear until adulthood, exist for all NSAIDs.

Benefits coming from intraarticular glucocorticoid injection were verified in a study of 43 patients with oligoarticular JIA. Remission lasting more than six months was gained in 82 percent of injections (115 of 141 injections), discontinuation of all oral medications happened in 74 percent of patients (32 patients), correction of joint contracture was observed in 55 joints, & complete remission was achieved among all 11 patients with Baker’s cysts & all 12 with tenosynovitis. No infections or other severe complications were noted in this study.

The dose of intraarticular glucocorticoid utilized depends upon both the size of the child & the size of the affected joint. Joint injection, involving glucocorticoid choice and dosing, is discussed in greater detail separately.

Escalation of therapy

Intraarticular glucocorticoid injection should improve arthritis for at least 4 months. A trial of a DMARD, generally methotrexate, is recommended if a patient with severe disease activity, moderate disease activity & poor prognosis, does not react to joint injection therapy. Sulfasalazine & leflunomide are alternate DMARDs available if the child has contraindications or intolerance to methotrexate. If a patient reacts to intraarticular glucocorticoids but needs repeated injections because of disease flares, the patient also becomes a candidate for DMARD therapy. This latter group involves both those with moderate disease activity & no features of poor prognosis as well as those with low disease activity & poor prognostic features.

Methotrexate is also utilized in patients who develop additional joint inclusion (extended oligoarthritis). As an example, a randomized trial in 43 children with extended oligoarticular JIA reported significantly great improvement in children administered methotrexate as determined by parent or caregiver & clinician global assessments. There was also a greater decline in both the mean ESR & CRP levels in methotrexate-treated children.

Patients are advanced to a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor (adalimumab, etanercept, or infliximab) if they continue to have moderate-to-high disease activity after 3 months of a nonbiologic DMARD & have poor prognostic features. The patient might be tapered off the DMARD once disease control is attained on a TNF inhibitor, although there is a large practice variation regarding when to stop the DMARD. A TNF inhibitor is also given in patients who continue to have high disease activity without poor prognostic features after six months of methotrexate therapy. TNF-alpha is more likely to play a significant role in the case process in patients with persistent disease activity. These patients are more likely to have extended oligoarthritis.

Infliximab & adalimumab are routinely utilized to treat uveitis in children who have progression or persistence of ocular inflammation despite the use of topical ophthalmic glucocorticoids & systemic medications such as methotrexate

The time period of therapy for methotrexate and for TNF inhibitors is similar to the approach used for polyarticular JIA & is discussed in detail separately.

Medication safety monitoring in patients on DMARDs (methotrexate or TNF inhibitor) is discussed in detail individually.

Immunizations

Live vaccines should not be given to children who are receiving systemic immunosuppression. In the absence of immunosuppression, routine childhood vaccines should be administered to all children with Juvenile idiopathic arthritis, regardless of disease activity.

Historically, immunizations, particularly with live-virus vaccines such as the measles, mumps, & rubella (MMR) vaccine, have been avoided in patients with JIA for several reasons. First, there is some question about the impact of immune stimulation from immunizations on juvenile idiopathic arthritis, both with regards to induction of arthritis and as a cause of disease flares, although data are limited and conflicting. In addition, patients on immunosuppressive therapy might develop infections from live-virus vaccines and might not develop protective responses to killed vaccines. Thus, the rate of execution of the MMR vaccine is still little in this population.

Nevertheless, no increase in JIA disease activity or medication use after MMR vaccination was seen in several observational studies, which involved patients on methotrexate with or without etanercept, nor were overt measles, mumps, or rubella infections reported. A normal immunologic response & no significant increase in JIA disease activity was seen in a randomized, open-label trial of MMR booster vaccination in 137 patients (131 analyzed). This study involved 15 patients on biological agents (discontinued prior to vaccination) & 60 patients on methotrexate. Sixty-five % of patients in this study had oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, & most patients had low disease activity. These findings recommend that a booster MMR vaccine can be administered to patients with oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Further studies are required in this region, particularly regarding the safety of primary immunization with live-virus vaccines in patients with all types of juvenile idiopathic arthritis who have the inactive disease & are not on immunosuppressants, and booster vaccination in patients who have other forms of juvenile idiopathic arthritis, who have moderate-to-high disease activity, & who are on biologic agents.

The outcome from an observational study advocates that the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine is safe to administer in adolescent girls with juvenile idiopathic arthritis, although patients had a lower immunologic response to the vaccine than healthy controls.

How shortly after treatment will the patient feel better?

Depending on the severity of the child’s diagnosis and the effectiveness of treatment, oligoarthritis can last for a few months to years. Symptoms frequently get less severe & can go away over time with treatment (remission). Sometimes, oligoarthritis spreads to other joints in a child’s body as they grow. Following your provider’s unique treatment plan will progress your recovery.

Physiotherapy treatment for oligoarthritis:

Physical therapy is an important part of the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. It is important for the child to stay active & involved in sports and activities with their peers & friends. While pain may limit the amount of activity a child can handle it is important to encourage involvement during periods of remission and allow rest and symptom-reducing therapies during periods of flare-ups. Regular activity and general exercise programs help to maintain the range of motion in affective joints, build and maintain strength, maintain function, and can even help with symptom reduction.

Aspects that should be focused on during a physical therapy program are as follows:

- Muscle tone

- Strengthening

- Range of motion

- Stretching

- Education on joint protection

- Home exercise plan

- Education on pain-reducing techniques

- Muscle relaxation techniques

- Splints or Introduction to Orthotics might be beneficial to help maintain normal bone & joint growth or prevent deformities during growth

Some modalities that can be utilized to help reduce symptoms such as pain are:

- Ultrasound

- Paraffin wax Bath dips (hands & feet primarily)

- Moist compress (hot pack)

- Hydrotherapy (warm)

- Cold packs

What is the course and prognosis of oligoarthritis?

Twenty-five to 35 percent of children with oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis extend to involve five or more joints within several years of diagnosis (extended oligoarthritis). In one study, 70, 65, and 50 percent of children with oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis achieved an American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Pediatric 30, 50, or 70 response, respectively, approximately six months after diagnosis. In this same cohort, 86 percent of patients with oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis attained inactive disease within two years, and 58 percent achieved remission within five years.

In comparison to children with extended oligoarthritis, those children with persistent typical oligoarthritis that includes fewer than five joints have a better chance of achieving remission. In one longitudinal study with a follow-up median of 98 months after diagnosis, 69 percent of children with persistent oligoarthritis attained remission. In that same study, only 37 percent of children with extended oligoarthritis attained remission

What can I expect if I have a child with oligoarthritis?

Oligoarthritis affects the joints in a child’s body, which could make it difficult for them to be active like other children their age, especially without treatment. Most children outgrow the condition as they enter adulthood. Some children will experience more joint discomfort as they age in other parts of their bodies. Treatment reduces joint pain & stiffness and physical therapy improves child’s mobility to allow them to move and play without restriction.

FAQ (frequently asked questions)

Can oligoarthritis be cured?

Although no cure exists for oligoarticular juvenile arthritis, many therapies can be used to ease disease symptoms & improve quality of life. Physicians might prescribe steroids, or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen, to limit pain & inflammation.

What is the difference between oligoarthritis and polyarthritis?

Oligoarthritis & polyarthritis are both types of idiopathic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The difference between both conditions is that oligoarthritis affects fewer than five joints, most frequently the large joints like the knees, ankles, & elbows, and polyarthritis affect five joints or more, & more frequently smaller joints in the hands and feet.

What is the most commonly affected joint in oligoarthritis?

Oligoarthritis affects about two-thirds of children & young people with arthritis and most usually affects one or both knees.

3 Comments