Larynx

Table of Contents

Overview

The larynx, additionally referred to as the box of speech, lives in the proximal neck. Vocalization, the cough reflex, and lower respiratory tract protection are just some of its critical functions as a component of the respiratory process. The establishment of a system of ligaments and membranes maintains the larynx’s mostly cartilaginous structure together.

Anatomical Position and Relations

The larynx forms from the hyoid bone and is found in the anterior part of the neck, between the C3 and C6. It merges inferiorly with the trachea after passing superiorly into the pharyngeal segment. It has a strong connection with the greatest blood vessels in the neck, which expand laterally to the larynx.

This is clinically significant during emergency intubation when cricoid pressure, also referred to as Sellick’s flexibility, can be applied to the larynx’s cricoid cartilage to narrow the esophagus and stop the Heat from refluxing your stomach’s stuff.

Anatomical Structure

The primary goal is to protect the lower airway by inhibiting respiration and preventing foreign objects from entering the airway by closing suddenly in response to mechanical stimulation. The larynx is also responsible for the Valsalva maneuver, coughing, controlling breathing, producing sound (phonation), and functions as a sensory organ. Despite not being a component of the larynx, the hyoid bone gives muscle attachments from above that facilitate laryngeal mobility.

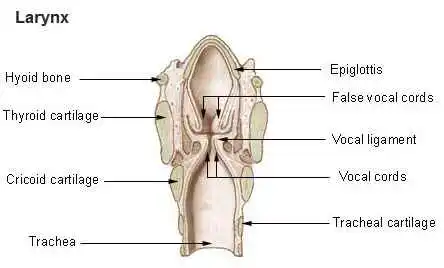

Cartilages of the larynx

Cricoid cartilage

A vertical midline ridge that functions as a connection to the esophagus separates the two oval depressions on the posterior surface of the lamina, which are insertion sites for the posterior cricoarytenoid muscles.

On the outer posterolateral surface of both edges of the ring, there are miniature, circular articular facets that articulate with the inferior horn of the arch where the lamina and arch contact.

Thyroid cartilage

The laryngeal prominence, often shortened to Adam’s apple, is formed with a right and a left lamina that join together at an acute angle in the anterior midline after dividing posteriorly. The two quadrilateral laminae represent the thyroid cartilage’s lateral surfaces, which cover the trachea on all sides obliquely. The lamina has an inferior horn and a superior horn that results from the extension of its posterior face.

Epiglottis

To prevent the larynx from releasing liquids or food that gets swallowed, the leaf-shaped cartilage described as the epiglottis improves to cover the glottis. Its stem attaches it to the midline of the inner region of the thyroid cartilage in the spot that includes the inferior notch and the angled section that forms the laryngeal prominence.

Aryepiglottic folds are many folds on the other side of the epiglottis. The regions located on both edges of the median fold that protect the tongue’s root and its epiglottis are additionally referred to as the valleculae epiglottic.

Arytenoid cartilages

Arytenoid cartilages describe the section of the larynx wherever fibers and folds that facilitate speech interact. With three surfaces, a base, and an apex, they form a pyramidal shape. There are two depressions on the anterolateral surface where the vocalis muscle and the vestibular ligament, or pretend vocal cord, might be united.

Ligaments of the larynx

Extrinsic ligaments

From the hyoid bone above to the superior edges of the thyroid cartilage in other bones the fibroblastic ligament known as the thyrohyoid membrane develops. Each side has an opening for the lymphatics, nerves, and superior laryngeal arteries on the lateral sides. The cricotracheal ligament binds the lower border of the cricoid cartilage to the following margin of the first tracheal cartilage ring.

Intrinsic ligaments

The conus elasticus is a submucosal membrane that arises uppermost from the anterior arch of the cricoid cartilage. Once enclosed by mucosa, the vocal folds (actual vocal cords) are formed by the thickening of the vocal ligament, which is created by the free superior border of the conus elasticus.

After being coated by mucosa, the vestibular folds (false vocal cords) are formed by the thickening of the free lower inferior margin of this membrane, which is known as the vestibular ligament.

Cavities of the larynx

Laryngeal cavity

The laryngeal inlet, the superior side of the cavity, opens inferiorly and posteriorly to the tongue into the pharynx. The inferior borders of the cavity and the pulmonary lumen are identical. The vestibule, middle, and infraglottic space are the three primary components that constitute the laryngeal cavity.

Laryngeal ventricles and saccules

The walls of these saccules have been proven to include several kinds of saliva glands that lubricate the folds of the throat.

Piriform recesses

The laryngopharynx’s anterolateral wall has piriform recesses (piriform sinuses) on either side. They frequently occur when food gets stuck.

Muscles of the larynx

Cricothyroid muscles

The external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve, a branch of the vagus nerve, stimulates only these laryngeal muscles below the base of the skull(cranial nerve [CN] X). Higher-pitch phonation results from the vocal cords becoming tense and elongated.

Posterior cricoarytenoid muscles

On both ends, the posterior cricoarytenoid muscles rise from the oval spaces on the posterior surface of the cricoid lamina to the arytenoid cartilage’s muscular process. By laterally extending among the arytenoid cartilages, these muscles extend the cords of the voice. The lateral cricoarytenoid muscles’ action is in opposition to theirs.

Lateral cricoarytenoid muscles

The side’s lateral cricoarytenoid muscle crosses from the cricoid cartilage’s upper border to the arytenoid cartilage’s muscular process on the same side. The arytenoid cartilages undergo rotation medially by these muscles, which adduct the auditory cords.

Transverse arytenoid muscle

The transversal arytenoid muscle is the only type of muscle that occupies the posterior angles inside either arytenoid cartilage. Both frequent laryngeal branches of the vagus nerves innervate it, and its primary function is the adduction of the vocal cords.

Thyroarytenoid muscles

The vocalis and the thyroepiglottic portion are the two components that jointly make up each muscle.

Nerves of the larynx

Superior laryngeal nerve

The vagus nerve‘s inferior ganglia connect to the superior laryngeal nerves, which in turn get branches from the superior cervical sympathetic ganglion on the left or right of the upper neck. Voice hoarseness and an inability to develop high-pitched sounds are caused by damage to this nerve after thyroidectomy or cricothyrotomy.

Recurrent laryngeal branch of the vagus nerve

The vagus nerves’ recurrent laryngeal branches grow into the larynx, which is located in the groove between the trachea and the esophagus. The right recurrent laryngeal nerve arises in the neck, as the left recurrent laryngeal nerve exits in the thorax and covers behind the aortic arch before ascending.

Vasculature

The items that follow blood flow received by the larynx from the superior and inferior laryngeal arteries:

Superior laryngeal artery –The first internal carotid contributing is the individual connecting to the laryngeal artery.

Inferior laryngeal artery – The branch’s proximal thyroid arteries terminate in the thyrocervical cord. It approaches the larynx through the pathway of the recurrent lingual nerve.

Clinical relevance

Speech production occurs via the vocal cords. The laryngeal nerve that recurs is sensitive to injury because of its extended commuting. RLN palsy can be caused by:

- Apical lung tumor

- Thyroid cancer

- Aortic aneurysm

- Cervical lymphadenopathy

- Iatrogenic (specifically while following thyroid surgery because of the intimate connection to the inferior thyroid artery).

One vocal cord is paralyzed in unilateral RLN palsy. However, the patient may experience fainting. of voice, speaking is not significantly impaired because the other vocal nerve tends to compensate. Both vocal cords are paralyzed in a position intermediate between adduction and abduction in cases of bilateral palsy. The rima glottidis, or space between the vocal cords, is entirely closed if this develops on both sides, and immediate surgery is needed to open the airway.

FAQs

What is the larynx and exactly how does it work?

The front side of the neck includes the larynx, a cartilaginous portion of the respiratory tract. In humans and other vertebrates, the larynx’s main task is to prevent food particles from being absorbed into the trachea while breathing.

Which three laryngeal various types are there?

The upper part (supraglottis).

The middle part (glottis).

The lower part (subglottis).

Where exactly is your larynx?

The voicebox is a substitute for the larynx. It requires up capacity in the neck, beyond the windpipe (trachea), and in front of the throat gullet (esophagus). The tube that food glides down when you eat is called the gullet.

Which muscles contribute to the larynx?

In combination, the pharynx’s stylopharyngeus, palatopharyngeus, and pharyngeal constrictor muscles and the muscles placed on the superior aspect of the hyoid (geniohyoid, digastric, mylohyoid, thyrohyoid, and stylohyoid muscles) erect the larynx.

What is the larynx’s blood supply?

The external carotid artery and the subclavian artery are two significant blood arteries that give blood to the larynx.

References

- Vashishta, R., MD. (n.d.). Larynx anatomy: gross anatomy, functional anatomy of the larynx, laryngeal tissue. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1949369-overview

- Professional, C. C. M. (2024a, May 1). Larynx (Voice Box). Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/21872-larynx

- Larynx. (2024, September 29). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Larynx