Dysarthria

Table of Contents

What is a Dysarthia?

Dysarthria is a speech disorder that affects a person’s ability to speak clearly and effectively. It is caused by damage to the parts of the brain that control the muscles used in speech, such as the lips, tongue, vocal cords, and diaphragm.

People with dysarthria may have difficulty with various aspects of speech, including articulation, pronunciation, volume, and intonation. They may speak in a slow, slurred, or mumbled manner, or their speech may be overly loud or soft.

Dysarthria can be caused by a wide range of conditions, including stroke, traumatic brain injury, Parkinson’s disease, cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Treatment for dysarthria typically involves speech therapy to help improve communication skills, as well as addressing any underlying medical conditions.

Dysarthria is a motor-speech disease. It happens when you can’t coordinate or maintain the muscles utilized for speech presentation in your face, mouth, or respiratory system. It usually results from brain damage or neurological condition, such as a stroke.

Dysarthria is a speech sound condition resulting from neurological damage of the motor segment of the motor–speech system and is characterized by the poor representation of phonemes. In other phrases, it is a condition in which issues actually occur with the muscles that help make a speech, often creating it very difficult to pronounce words. It is irrelevant to problems with understanding language (dysphasia or aphasia), although a person can have both.

Any speech subsystems (respiration, phonation, resonance, prosody, and articulation) can be involved, leading to impairments in intelligibility, audibility, innocence, and efficiency of vocal transmission. Dysarthria that has advanced to a total failure of speech is referred to as anarthria. The duration dysarthria is from New Latin, dys- “dysfunctional, defective” and author- “joint, vocal articulation”.

Dysarthria can be developmental or received:

Developmental dysarthria occurs due to brain injury during fetal expansion or at birth. For example, cerebral palsy can cause dysarthria. Children grow to have developmental dysarthria.

Acquired dysarthria occurs as a result of brain injury later in life. For example, a stroke, a brain tumor, or Parkinson’s disorder can direct to dysarthria. Adults grow to have acquired dysarthria.

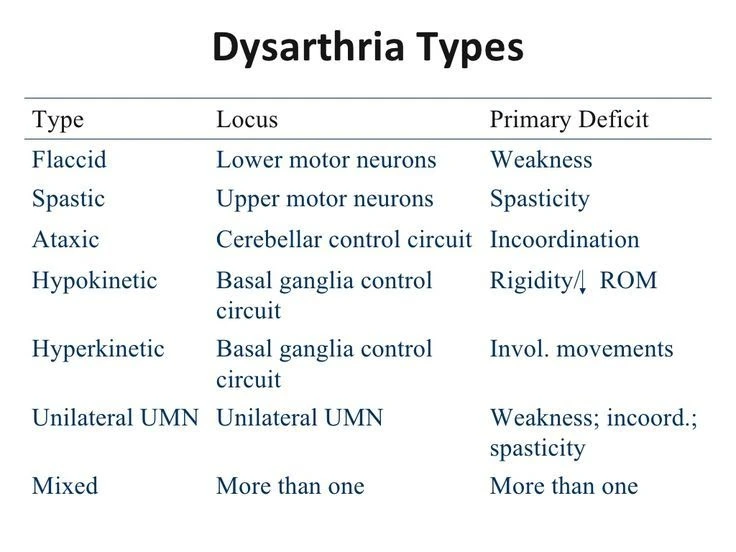

What are the classes of Dysarthria?

There are six classes of dysarthria. They’re grouped based on the exact part of your nervous system involved. Dysarthria may result from injury to various regions of your nervous system, including your brain and spinal cord (central nervous method) and the grid of nerves that maintain signals throughout your body (peripheral anxious system).

- Flaccid dysarthria effects by injury to the lower motor neurons. The lower motor neurons are regions of your peripheral nervous system. With flaccid dysarthria, your speaking may voice breathy and nasal.

- Spastic dysarthria effects by injury to the upper neurons on one or both flanks of your brain. The upper neurons are regions of your central nervous system. Your speaking may sound strained or difficult.

- Ataxic dysarthria effects from injury to the part of your brain called the cerebellum. Your cerebellum allows coordinate muscle motion. You may have trouble pronouncing vowels and consonants, and you may have a problem placing stress on the right regions of a word when you’re emitting it.

- Hypokinetic dysarthria develops from injury to the part of your brain called the basal ganglia. The basal ganglia is a structure inside your brain that helps your muscles progress. Hypokinetic dysarthria is associated with gradual (“hypo”), monotone, rigid-sounding speech.

- Hyperkinetic dysarthria also results from injury to your basal ganglia. It’s associated with fast (“hyper”) communication and often unpredictable speech.

- A combination of two or more of the other five kinds can occur in mixed dysarthria. The most common kind of dysarthria is this one.

Symptoms of Dysarthria

Depending on the underlying cause and the type of dysarthria, the signs, and symptoms can vary. They could include:

- Slurred speech

- Slow speech

- Incapability to speak louder than a whisper or talking too loudly

- Fast speech that is challenging to understand

- Nasal, raspy, or strained voice

- Uneven or strange speech rhythm

- Irregular speech volume

- Monotone speech

- Problem proceeding with your tongue or facial muscles

Causes of Dysarthria

You can have trouble controlling the upper respiratory system, and facial, or mouth muscles that affect your speech if you have dysarthria. Conditions that may direct to dysarthria contain:

- Lou Gehrig’s disease, also known as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- Brain damage

- Brain tumor

- Cerebral palsy

- Guillain-Barre syndrome

- Head injury

- Huntington’s disorder

- Lyme disease

- Multiple sclerosis

- Muscular dystrophy

- Myasthenia gravis

- Parkinson’s disorder

- Stroke

- Wilson’s disease

- Some medications, such as specific sedatives and seizure drugs, also can induce dysarthria.

Diagnoses

Your healthcare provider will ask about your medical record and do a physical exam. A speech-language pathologist (SLP) may consider you to decide how powerful your dysarthria is. They’ll inspect your capacity to harmonize your breathing, voice, and the rate of your voice. And they’ll check your capability to carry your lips, tongue, and face.

They may ask you to:

- Punch out your tongue.

- Smile, ruffle, or lick your lips.

- Count or display the alphabet out of the noise.

- Read a section.

- Duplicate sounds, words, and sentences, and talk in discussion.

Other tests may include:

- MRI or CT scans of your brain, head, and neck to check for abnormalities that may impact your speech.

- Electroencephalogram (EEG) to inspect for abnormalities in your brain exercise related to dysarthria.

- Electromyography pushes the electrical part of your muscles and nerves.

- Blood or urine examinations to see if a disease or inflammation is causing speech problems.

- Spinal tap (lumbar hole) to see if a disease or tumor is pushing dysarthria.

Treatment of Dysarthria

A speech-language pathologist may be capable to help you enhance your communication capabilities. They may create a custom treatment program to help you:

- Raise tongue and lip motion.

- Maintain your speech muscles.

- Slow the rate at which you communicate.

- Enhance your breathing for louder speech.

- Enhance your articulation for clearer speech.

- Practice group communication talents.

- Try your communication skills in real-life situations.

- Hold a notebook or smartphone with you. If someone doesn’t understand you, author, or type what you want to say.

- Make sure you have the other individual attention.

- Talk slowly.

- Talk face-to-face if you can. The other individual will be able to comprehend you better if they can visit your mouth impact.

- Try not to speak in loud places, like at a restaurant or party. Before you speak, turn down the music or the TV, or go outdoors.

- Abuse facial phrases or hand motions to get your point across.

- Utilize short phrases and words that are more comfortable for you to communicate.

How to Prevent Dysarthria?

Dysarthria can be pushed by numerous conditions, so it can be hard to control. But leading a healthy lifestyle that lowers your risk of stroke can help you lower your risk of dysarthria. For example:

- Exercise regularly.

- Keep your weight at a healthful level.

- Improve the amount of fruits and vegetables in your diet.

- Restrict cholesterol, saturated fat, and salt in your diet.

- Restrict your infusion of alcohol.

- Evade smoking and secondhand moisture.

- Don’t abuse drugs that aren’t defined by your doctor.

- If you’re interpreted with high blood pressure, take measures to control it.

- If you have diabetes, follow your doctor’s suggested therapy plan.

- If you have obstructive rest apnea, seek therapy for it.

FAQs

Cranial nerves that maintain the muscles relevant to dysarthria contain the trigeminal nerve’s motor department (V), the facial nerve (VII), the glossopharyngeal nerve (IX), the vagus nerve (X), and the hypoglossal nerve (XII).

In someone with dysarthria, a nerve, brain, or muscle condition causes it challenging to utilize or maintain the muscles of the mouth, tongue, larynx, or vocal cords. The muscles may be ineffective or totally paralyzed.

Ministering the underlying cause of your dysarthria may enhance your speech. You may also require speech therapy. For dysarthria pushed by prescription medications, changing or discontinuing the medications may benefit.

2 Comments