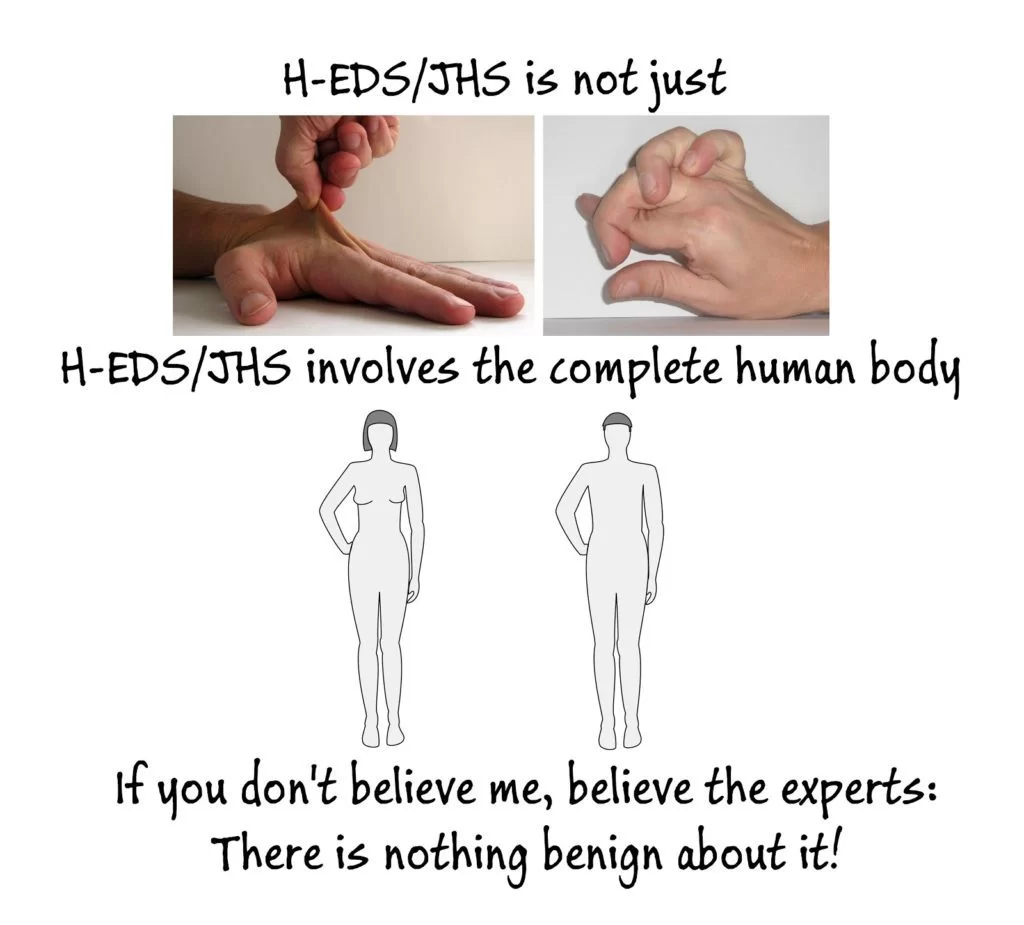

Benign joint hypermobility syndrome: Cause, Symptoms, Treatment

Benign joint hypermobility syndrome means your joints are “looser” than normal. It’s typically referred to as being double-jointed. It is a common joint or muscle problem in children and young adults.

Formerly known as benign hypermobility joint syndrome (BHJS), the condition can cause pain or discomfort after exercise. It’s usually not part of any disease.

The hypermobility syndrome was first described in 1967 by Kirk et al as the occurrence of musculoskeletal symptoms in hypermobile in healthy persons. Meanwhile, other names are given to HMS, such as joint hypermobility syndrome and benign hypermobility joint syndrome. HMS is a dominant inherited connective tissue disorder described as “generalized articular hypermobility, with or without subluxation or dislocation. The primary symptom is excessive laxity of multiple joints.

Hypermobility syndrome is different from localized joint hypermobility and other disorders that have generalized joint hypermobility, such as Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, and Marfan Syndrome.HMS may occur also in chromosomal and genetic disorders such as Down syndrome and in metabolic disorders such as homocystinuria and hyperlysinemia. Laboratory tests are used to exclude these other systemic disorders when HMS is suspected.

Benign joint hypermobility syndrome (BJHS) is the occurrence of musculoskeletal symptoms in hypermobile individuals in the absence of systemic rheumatologic disease. This syndrome is thought to be an inherited connective tissue disorder. The primary clinical manifestations of BJHS are hypermobility and pain in multiple joints. This syndrome is different from other disorders that cause local joint hypermobility and generalized joint laxity, such as Marfan syndrome and Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (EDS).

The Brighton criteria are used to diagnose BJHS, and laboratory tests are used to distinguish BJHS from other systemic diseases. Other criteria have been proposed for diagnosis, including Bulbena’s criteria; however, the criteria defined by Brighton are the ones most frequently cited in the literature.

Generalized joint laxity is commonly seen in healthy individuals who do not have complaints. Hypermobility that is not associated with systemic disease occurs in 4% to 13% of the population. Hypermobility diminishes as one age, and it also appears to be related to sex and race.5 In general, women have greater joint laxity than men, and up to 5% of healthy women have symptomatic joint hypermobility compared with 0.6% of men. People of African, Asian, and Middle Eastern descent also have increased joint laxity.

Among studies examining the prevalence of generalized hypermobility in patients referred to rheumatologists, one study found that hypermobility occurred in 66% of school children with arthralgia of unknown etiology. Another study showed a similar prevalence of hypermobility in children; however, there was no association between hypermobility and the development of arthralgia. These data suggest that generalized hypermobility exists without joint pain and it does not necessarily lead to arthralgia. Furthermore, patients with hypermobility often lead normal lives and do not have BJHS or another connective tissue disorder.

Hypermobility may occur in several different connective tissue disorders including Marfan syndrome, EDS, and osteogenesis imperfecta. It may also be found in chromosomal and genetic disorders such as Down syndrome and in metabolic disorders such as homocystinuria and hyperlysinemia. Recurrent dislocation of the shoulder and patella as well as other orthopedic abnormalities are associated with joint laxity. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis may also be associated with hypermobility, but many times, systemic symptoms are involved. Patients with BJHS have generalized hypermobility as well as chronic joint pain and other neuromusculoskeletal signs related to a defect in collagen.

Benign joint hypermobility syndrome has a strong genetic component with an autosomal dominant pattern. First–degree relatives with the disorder can be identified in as many as 50% of cases. The syndrome appears to be due to an abnormality in collagen or the ratio of collagen subtypes. Mutations in the fibrillin gene have also been identified in families with BJHS.

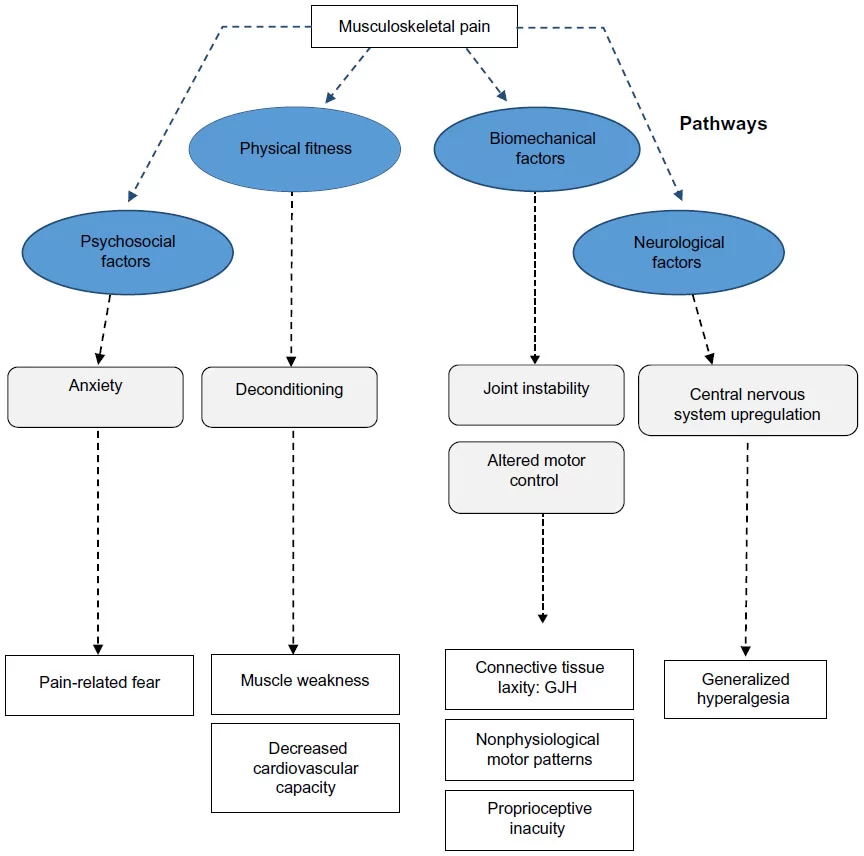

So, why do patients with BJHS present mainly with joint pain? It is thought that excessive joint laxity leads to wear and tear on joint surfaces and strains or fatigues the soft tissue surrounding these joints. Some studies also suggest that proprioception in the joints of patients with BJHS is impaired. This impairment can also lead to excessive joint trauma due to impaired sensory feedback from the joint affected.

Table of Contents

Related Anatomy :

The pathophysiology of Hypermobility Syndrome is not yet fully understood, it appears to be a systemic collagen abnormality. The abnormality in collagen ratios is related to joint hypermobility and laxity of other tissues. The ratio of collagen (type I, II, and III) is decreased in the skin. The diagnostic criteria for HMS include joint abnormalities but it also affects cardiac tissue, smooth muscle in the female genital system and the gastrointestinal system. HMS also affects the joint position sense.

Cause of Bening joint hypermobility syndrome

Joint hypermobility happens most often in children and reduces with age. Joint mobility is highest at birth, there is a decrease in children around nine to twelve years old.

In adolescent girls, there is a peak at the age of fifteen years, after this age joint mobility decreases, as well in boys as in girls. Hormonal changes that occur in puberty by adolescent girls, will influence joint mobility.

In general, hypermobility is more common in children than adults, is more common in girls than in boys, more common in Asian, African, and middle eastern people.

Clinical Presentation

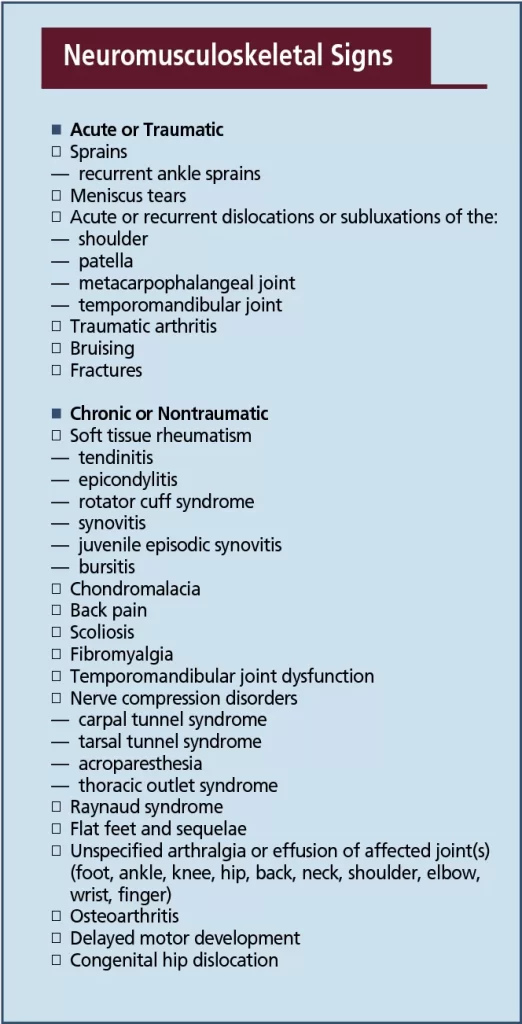

Possible Neuro-musculoskeletal Signs in Individuals with hypermobile joint syndrome:

- Acute or Traumatic sprains: – recurrent ankle sprains

- Meniscus tears

- Joint instability: Acute or recurrent dislocations or subluxations of the shoulder, patella, metacarpophalangeal joint, and temporomandibular joint

- Traumatic arthritis

- Bruising

- Fractures: chronic or non-traumatic

- Chondromalacia Patellae

- Scoliosis

- Fibromyalgia

- Chronic fatigue syndrome

- Nerve compression disorders- Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome, Acroparesthesia, Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

- Raynaud syndrome

- Flat feet and sequelae

- Unspecified arthralgia or effusion of affected joint(s)- (foot, ankle, knee, hip, back, neck, shoulder, elbow, wrist, finger)

- Back pain

- Osteoarthritis

- Delayed motor development

- Congenital hip dislocation

- Exercise-related/post-exercise-related pains

- Nocturnal leg pains

- Low nocturnal sleep quality

- Joint swelling

- Clumsiness

- Enhanced flexibility

- Chronic pain

- Little changes in the skin

- Greater risk of failures in tendon, ligament, bone, skin, and cartilage

- Functional gastrointestinal disorders

- Chronic headache

- Immune system dysregulations

- Pelvic dysfunction

- Cardio-vascular dysautonomia

- Exocrine glands dysfunction

- Ankylosing Spondylitis

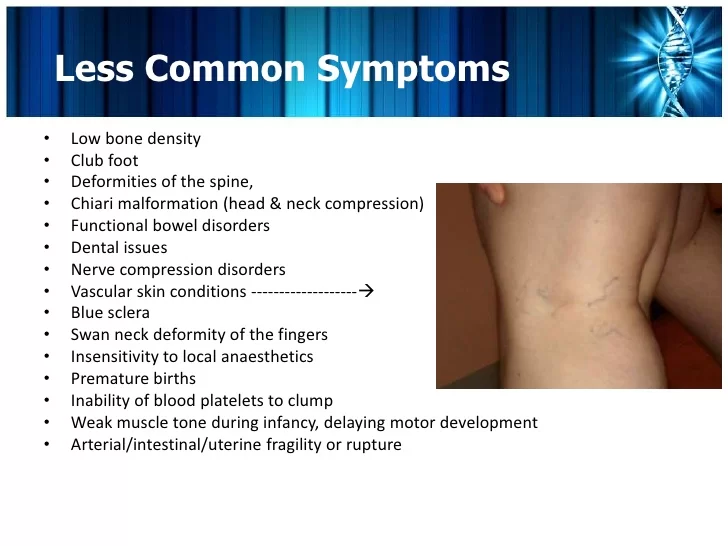

The signs and symptoms of BJHS are variable. Most commonly, the initial complaint in a hypermobile patient is joint pain, which may affect one or multiple joints and may be generalized or symmetric. Primary care physicians can use the five simple questions to aid in recognizing hypermobility. The onset of symptoms can occur at any age, and many patients have been referred to specialists in orthopedics, rheumatology, or physiatry. Typically, children have self-limited pain in multiple joints; however, pain can last for a prolonged time and may become constant in adulthood. Pain may involve any joint but most commonly involves the knee and ankle, presumably because they are weight–bearing joints.

Physical activity or repetitive use of the affected joint often exacerbates the pain. Consequently, pain usually occurs later in the day and morning stiffness is uncommon. Less common symptoms are joint stiffness, myalgia, muscle cramps, and nonarticular limb pain. Patients with BJHS often say that they are “double-jointed” or that they can contort their bodies into strange shapes (ie, volitionary subluxation) or do the splits. Such an admission, however, is not necessary for including BJHS in the differential diagnosis. Patients with BJHS may also have a history of shoulder or patellar dislocation.

Patients with BJHS may have a family history of “double-jointedness” or recurrent dislocations. Other presentations include easy bruising, ligament or tendon rupture, congenital hip dysplasia, and temporomandibular joint dysfunction.

Findings of the physical examination vary based on the joint saffected. Pain in response to manipulation of the joint is common. Mild effusions are not common but may be present. Clinically significant tenderness along with redness, swelling, fever, or warmth suggests inflammation and is not present in patients with BJHS.

Signs of a typical connective tissue disorder may be present, including scoliosis, pes planus, genu valgum, lordosis, patellar subluxation or dislocation, marfanoid habitus, varicose veins, rectal or uterine prolapse, and thin skin . The association of BJHS with mitral valve prolapse (MVP) is a subject of controversy. Early studies showed an association between MVP and BJHS, but later studies have questioned this association because of stricter echocardiographic criteria for MVP. Primary care physicians should refer patients with hypermobility in whom cardiac findings suggest MVP to a cardiologist for further evaluation to rule out more serious cardiac abnormalities and connective tissue disorders.

Symptoms of Bening joint hypermobility syndrome

Children or young adults with hypermobility sometimes have joint pain.

The pain is more common in the legs, such as the calf or thigh muscles. It most often involves large joints such as the knees or elbows. But it can involve any joint.

Some people also have mild swelling in the affected joints, especially during the late afternoon, at night, or after exercise or activity. That swelling may come and go within hours.

Differential Diagnosis

The signs and symptoms of hypermobility syndrome are variable. Most commonly, the initial complaint in a hypermobile patient is joint pain, which may affect one or multiple joints and may be generalized or symmetric. Primary care physicians can use the five simple questions to aid in recognizing hypermobility. Other complaints are muscle cramps.( after physical activity) and joint stiffness. People with HS can suffer from subluxations and dislocations.

Diagnosis

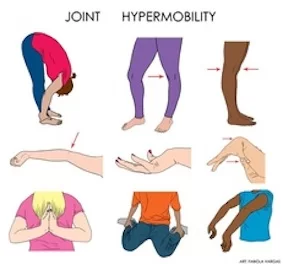

Simple tests show whether a child has a greater range of motion in their joints than normal. Doctors use several specific mobility tests, including:

- The wrist and thumb can be moved downward so the thumb touches the forearm.

- The little fingers can be extended back beyond 90 degrees.

- When standing, the knees are abnormally bowed backward when viewed from the side.

- When fully extended, the arms bend further than normal (beyond straight).

- When bending at the waist, with the knees straight, the child or adult can put their palms flat on the floor.

- Since the symptoms of hypermobility can sometimes mimic arthritis, you may need to get lab tests to make sure your child doesn’t have a more serious disorder (such as juvenile arthritis or other inflammatory conditions). In rare cases, you may need to get X-rays.

Treatment of Bening joint hypermobility syndrome

Simple things can help with this condition, such as:

Regular Exercise. It’s a good idea to strengthen the muscles around loose joints. For some people, doctors recommend splints, braces, or taping to protect affected joints during activity.

Joint protection. These tips will help your child avoid overstretching their hypermobile joints:

Don’t sit cross-legged with both knees bent (“Indian style”).

Bend the knees slightly when standing.

Wear shoes with good arch supports.

Stop any unusual joint movements that hypermobile children often use to entertain their friends.

Physical Therapy Treatment :

The aim of physical therapy in hypermobility syndrome is to approach muscle inhibition, atrophy and reduced joint control caused by the joint pain. Another important step in treating hypermobility syndrome is education. Without this education patients will continue to go over the normal joint range and their extreme joint range can cause a more unstable joint. Fatigue, anxiety and depression are sometimes associated with HMS, and we must try to ameliorate their quality of life. It is necessary to encourage an active lifestyle, so give for example a schedule with exercises to fulfil at least 3 times a week.

Treatment overview:

- Education of hypermobility syndrome

- Activity modification

- Stretching exercise of the affected joint

- strengthening exercises for the affected joint

- osteopathic manipulative treatment

- Active mobilization exercises: shoulder rolls, arm circles, neck rotations, neck lateral flexions, wrist circles, side flexions of the spine, and thoracic rotations in sitting. Closed-chain exercises are good exercises in many regards: it may reduce strain on injured ligaments, augment proprioceptive feedback, and optimize muscle action. In the studies by Sahin et al. and Ferrell et al. they trained specifically with the knee joint, whilst the other two studies incorporated whole-body exercise interventions to treat joint hypermobility syndrome.

Strengthening exercises: stabilizing muscles around hypermobile joints can be effective for joint support during movement or can reduce pain. These included shuttle runs, bunny-hops, squat thrusts, sitting-to-standing, step-ups, and star jumps. (30 seconds or a predetermined number of repetitions)

Proprioception exercises: a decreased joint position sense (is there proof of this will make a patient more vulnerable to damage. Decreased sensory feedback may lead to biomechanically unsound limb positions being adopted, leading to abnormal postures. Coordination and balance exercises may improve proprioception. Exercise onboard balance wood (2 to 3 minutes), mini-trampoline jumping (30 reps), walking with eyes closed, single leg balance, single leg ball rolling, forward/backward bends on one leg (eyes open or closed)

Control neutral joint position: identifying the abnormal resting position of symptomatic joints, re-training postural muscles to facilitate optimal joint alignment (avoid hyperextension of the knee when standing)

Re-train dynamic control: once a ‘neutral’ resting position is achieved, re-training of specific muscles to maintain joint position while moving adjacent joints (hip flexion while maintaining spinal neutral) Dynamic control will be exercised with daily activities or sports.

Movement control: improving the ability of specific muscles to control the joint through its entire range, both concentrically and eccentrically, static and posture ( on sitting to standing quadriceps or working concentrically on standing up and eccentrically on sitting down)