Posterior ankle impingement syndrome

Ankle impingement is characterized as ankle pain brought on by impingement in either the ANTERIOR (anterolateral and anteromedial) or the POSTERIOR (posteromedial) portions of the ankle. Tibiotalar (talocrural) joint serves as a point of reference for the pain’s location. In general, Anterior ankle impingement describes the trapping of structures at the tibiotalar joint’s anterior edge during terminal dorsiflexion.

Posterior ankle impingement is caused by the compression of the tissues behind the tibiotalar and talocalcaneal articulations during terminal plantar flexion. Osteophyte-related mechanical blockage and/or the trapping of different soft tissue structures as a result of inflammation, scarring, or hypermobility are the two main causes of pain. Athletes, particularly soccer players, long-distance runners, and ballet dancers, frequently have the syndrome. Observed in athletes whose activities required quick acceleration, jumping, and severe dorsiflexion or plantar flexion. Other name for this condition is “footballer’s ankle” and “athlete’s ankle.”

Table of Contents

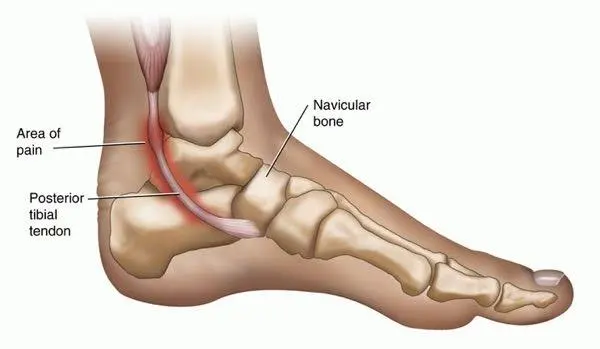

Anatomy

Talocrural Joint

A talus:

The synovial hinge joint in the ankle allows for up to 20 degrees of dorsiflexion and 50 degrees of plantarflexion. It is made up of the articular surfaces of the talus, tibia, and fibula. The medial (Deltoid) and lateral ligament complexes of the ankle hold the distal ends of the tibia and fibula firmly together. The tibia and fibula form a deep bracket-like configuration around the talus thanks to the ligaments.

- The distal inferior surface of the tibia serves as the joint’s ROOF.

- The medial malleolus of the tibia makes up the MEDIAL SIDE of the joint.

- The lateral malleolus of the fibula makes up the LATERAL SIDE of the joint.

Looking down at the talus, the articular portion is wider anteriorly than posteriorly and resembles a cylinder. It fits snugly into the bracket created by the syndesmosis of the tibia and fibula. As a result, when the joint is in dorsiflexion, it is more congruent and stable. Since this is a synovial joint, a membrane and a fibrous membrane are present, serving the same purposes as other synovial membranes in synovial joints.

Foot Articulations (Talus Removed)

Subtalar joint:

The Talocalcaneal joint, also known as the Subtalar joint, is situated between:

Both the equivalent posterior facet on the superior surface of the calcaneus and the big posterior calcaneal facet on the inferior surface of the talus.

This joint, because of its orientation, permits inversion and eversion movements of 0 to 35 degrees and 0 to 25 degrees, respectively. This implies that the joint also permits some gliding and rotation. A simple synovial condyloid joint is what it is called. The joint is supported by plenty of sturdy ligaments.

Posterior Ankle Impingement Syndrome(PAIS)

When the foot is pointing downward (plantar flexed), a condition known as posterior ankle impingement syndrome (PAIS) results, which causes severe pain in the rear of the ankle. This issue often develops in the hindfoot when an extra piece of bone, muscle, or ligament presses up on another anatomical part.

The condition known as “dancer’s heel” or posterior impingement (PI) is typically sneaky in nature and affects athletes who frequently plantarflex, such as ballet dancers, sportsmen who leap, and those who kick. Chronic ankle discomfort is frequently brought on by posterior ankle impingement. Bony or soft tissue impingement, in particular irritation of the flexor hallucis longus, thickening of the posterior capsule, synovitis, inversion trauma/sprain, forceful plantarflexion causing anterior sheering of the tibia, and hypertrophy of the os trigonum hitting the posterior tibia, maybe the reason. It is often referred to as posterior tibiotalar compression syndrome and os trigonum syndrome. The most frequent reason for symptomatic posterior ankle impingement is the os trigonum. There may be impingement in two sides Posteromedial or Posterolateral.

- Posteromedial impingement: Chronic posteromedial discomfort is primarily brought on by scar tissue made up of posterior fibres, which is known as posteromedial impingement. The fibers of the posterior ligament become crushed when the ankle is in plantar flexion due to an ankle inversion trauma. The posteromedial tibiotalar capsule and posterior tibiotalar ligament fibers are two of the components involved in posteromedial ankle impingement. They are more likely to become entrapped during supination because of their placement between the talus and medial malleolus. The injured posterior tibiotalar ligament and posteromedial capsule subsequently fibrose and thicken, which impinges on the medial wall of the talus and the posteromedial ankle and results in synovitis, collagenous and fibrous meniscoid lesions, and the posterior edge of the medial malleolus.

- Posterolateral impingement: The posterior talofibular ligament, also known as the posterior intermalleolar ligament, is the source of the posterolateral impingement injury. Although this ligament is an anatomical variation, 56% of people have it. The PTL will entrap during a plantar flexion and eventually tear.

PAIS can drastically reduce ankle range of motion and make some athletic activities, such rising up on your toes or pushing off your foot, quite uncomfortable, depending on its severity. The signs, causes, and remedies of posterior ankle impingement syndrome are covered in length in this article.

Causes of Posterior Ankle Impingement Syndrome:

PAIS disease may result from anatomic variations as well as osseous and/or soft tissue abnormalities. Osteophytes, osteochondral lesions (OCL), loose bodies, enchondromatosis, subtalar coalition, Stieda process (elongated protuberance), and pathological os trigonum (non-fused ossicle occurring in up to 25% of the normal adult population) are examples of osseous lesions. Flexor hallux longus (FHL) tenosynovitis, synovitis, impingement of the joint capsule, and impingement of the abnormal muscles are all examples of soft tissue diseases.

Who Is at Risk?

Athletes who engage in repetitive ankle plantar flexion exercises are more likely to develop posterior ankle impingement syndrome. This includes athletes who routinely stand on their toes, such as soccer players and ballet dancers who perform en pointe. A higher danger applies to cross-country or trail runners who run downhill frequently.

PAIS can develop in these athletes as a result of repeated plantar flexion over an extended period of time or as a result of an acute or forced plantar flexion movement.

Non-athletes can also develop the syndrome, though this is considerably less prevalent. These individuals frequently have posterior impingement as a result of a bone deformity that pinches the tissue in the hindfoot.

Symptoms of Posterior Ankle Impingement Syndrome:

Posterior:

The distinction between posterior ankle impingement syndrome and other painful disorders is made by a number of distinguishing features. When one points the foot downward or rises onto the toes, they experience profound ankle discomfort that is typical of this ailment.

The pain may continue even after the dance or sport has been completed, but it usually gets worse as you perform. PAIS sufferers typically struggle to define the particular area of their pain, which they may describe as intense, dull, persistent, or radiating.

Additionally, range of motion is frequently limited, and a distinct difference in downward flexion between the affected and unaffected foot may be noticed. If a more severe plantar flexion injury is present, there may also be swelling and redness in the area of the hindfoot.

Deep posterior ankle pain brought on by plantar flexion of the ankle joint is a defining feature of AIS.

When forceful plantarflexion or dorsiflexion is used, patients have more posterior ankle pain. The posterior tibiotalar joint’s joint line may also be painful (although not involving the achilles tendon). Plantar flexion of the ankle is restricted, and ligamentous instability and soft tissue hypertrophy are present.

Posteromedial: Tenderness to the posteromedial aspect following inversion with the ankle in plantar flexion is an important clinical finding for a patient with a posteromedial impingement. In passive ankle inversion and passive plantar flexion, tenderness is most noticeable. Additionally, the ankle’s posteromedial region is painful. This aids in separating the pain from a posterior tibialis anomaly.

Posterolateral: A patient who has a posterolateral impingement feels as though their ankle is locking, and they are in discomfort on the back of their ankle. An acute inversion injury with plantar flexion precedes the impingement. The posterior talofibular ligament is squeezed and ruptured, which causes it to enlarge. The most frequent sports where repeated plantar flexion occurs are ballet, soccer, and volleyball.

The following risks may arise when athletes with posterior impingement attempt to compensate for the loss of plantar flexion by standing with their feet inverted:

- Frequently sprained ankles

- Sprained calf Contractures

- Toe curled

- Planter foot discomfort

Type of pain:

- The pain in the hindfoot is reported as constant, severe, dull, and radiating, it is typically difficult for patients to pinpoint its exact position.

- Ballet dancers, soccer players, and downhill runners are among the athletes most likely to experience it. It is also more common in athletes who engage in activities that demand repetitive plantar flexion.

- PAIS may manifest immediately in these athletes following a forceful plantar flexion injury or persistently as a result of overuse.

Three to four weeks after an acute injury, patients experience a strong inflammatory reaction that causes pain and oedema to appear in the hindfoot. PAIS more frequently manifests over time in these athletes as a result of increased compression and forces on the anatomical structures between the calcaneus and the posterior portion of the distal tibia brought on by repetitive bending.

Differential diagnosis:

Posterior Ankle discomfort:

- Broken talus or calcaneus

- Tendinitis of the achilles

- Ankle impingement in the posterior side

- A flexor hallucis longus lesion that is isolated

- Bursitis of the retrocalcaneum

- Háglund’s malformation

- Tibial osteochondral injuries on the posterior side

- Tarsal tunnel

Medial side ankle pain

- Tarsal tunnel disorder

- Tibial tendinitis in the posterior

- Meningeal fractures

- Ankle medial impingement

- Pathology of the subtalar joint

- Shin splints, or medial tibial stress syndrome

Lateral side ankle pain:

- (Talus, Fibula, 5th Metatarsal) Fracture

- Harm to the pernoeal tendon

- Ankle impingement on the side

- Irritation of the sural or femoral nerve

- Subluxation of the cubit

Diagnosis:

Ankle oedema, dorsiflexion restriction, and chronic ankle pain are common concerns. For the diagnosis of bone impingement, imaging is helpful, but not for the diagnosis of soft tissue impingement, which is reliant on clinical findings.

Physical tests:

Along with assessing strength and range of motion, a physical examination should include a thorough neurovascular examination. A good result on the plantar flexion test is hindfoot pain made worse by ankle plantar flexion. However, no studies have examined the specificity or sensitivity of the plantar flexion test in the diagnosis of PAIS. A negative plantar flexion test greatly reduces the likelihood of a PAIS diagnosis. Patients may also have pain in the ankle joint’s posteromedial (PM) region. Since pain over the posterior tibial tendon may not be PAIS but rather posterior tibial tendon tenosynovitis or malfunction, the doctor must pay close attention to the precise area of tenderness. The doctor can passively flex and extend the great toe to pinpoint the pain’s source further. Tenderness in the patient during passive or active ROM may be a sign of disease affecting the FHL tendon. In order to rule out tarsal tunnel syndrome, a neurologic examination should be carried out because Valleix’s sign may be the source of the discomfort.

Examination of the posterior ankle impingement:

- Loss of mobility combined with pain in the back of the ankle during forced Plantarflexion

- Large posterior talar processes

- Test for hyper plantar flexion

Further tests:

- Posteromedial joint line deep pressure palpation: A plus sign is a sensitivity.

- Laxity tests (inversion and anterior drawer)

- Anterior tibialis, Peroneus complex, and gastrosoleus complex manual strength test

- Tests for flexibility: Hamstring, Achilles tendon

- Forced Inversion Forced Plantarflexion

Imaging tests:

Conventional radiography, which allows assessment of any suspected bone abnormalities, is typically the initial imaging modality used, especially in anterior and posterior impingement.

Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging has essentially replaced computed tomography (CT) and isotope bone scanning. Osteous and soft tissue oedema in anterior or posterior impingement can be shown on MR imaging.

The best imaging technique for assessing possible soft-tissue impingement is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Additionally, ultrasound can assess related ligament injuries, diagnose soft tissue impingement lesions in the anterolateral portion of the ankle, and distinguish between illness and bone impingement.

Radiographic characteristics

MRI: May show intact posterior talofibular ligament and posterolateral capsular thickening and synovitis.

Tenosynovitis affecting the flexor hallucis longus could exist.

may demonstrate one or more of the underlying anatomical characteristics

Associated bone contusion that affects the lateral tubercle of the posterior talar bone may be observed.

oedema and/or localized fluid in the posterior joint recesses

MRI signal’s properties:

T1: weak signal in the bone-bruising areas

T2/STIR: regions with bone bruise have a strong signal posterior to the ankle.

PD/PD fat saturated: strong signal from the ankle posterior

Treatment of Posterior Ankle Impingement Syndrome:

Non-surgical treatment:

Conservative therapy successfully treats posterior ankle impingement syndrome symptoms in up to 60% of cases. Nonsurgical therapies typically consist of:

- Resting or modifying activities to avoid triggering movements

- Icing

- Physical treatment to increase strength, reduce pain, and improve ankle mobility

- NSAIDs, such as Advil (ibuprofen) and Aleve (naproxen), are non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications.

- Injections using ultrasound guidance

Surgical Techniques:

About 40% of the time, surgery is required because conservative treatment is ineffective. Depending on where the pain in your ankle is coming from, a different type of surgery may be required.

It is considered after conservative treatment has been tried first for at least 3 months

The surgical approach and technique vary depending on the anatomic region and pathology involved.

A few surgical procedures include debridement, osteophyte removal, meniscoid lesion excision, partial capsulectomy, the release of the flexor hallux longus, and tibia chondroplasty.

Arthroscopic surgery is often utilized when the impingement is brought on by a bony accumulation on the talus bone of the ankle or by a piece of nearby accessory bone (os trigonum).

The part of the bone that is causing the symptoms is cut away or removed during this procedure. This lessens any posterior impingement, lessens your discomfort, and expands the ankle’s range of motion.

Similarly to this, excision of the underlying anatomy is required for surgery to treat posterior impingement. Excision of a painful trigonal process, or os trigonum, together with debridement of adjacent inflammatory or hypertrophic soft tissues, is the most typical method for relieving symptoms. Posterior pathology can be targeted through an open lateral, open medial, or endoscopic approach.A lateral approach reduces danger to the medial neurovascular bundle while providing more direct access to the trigonal process. Concomitant FHL pathology is easier to treat with a medial approach.

Arthroscopy may also be utilized to debride the ligament or muscle that is being squeezed in soft tissue impingement cases. Usually, while doing the surgery, your surgeon will passively plantar flex your foot while observing the various structures in your hindfoot to determine which ones are being compressed.

After this visual inspection, the problematic section of soft tissue is removed using an arthroscopy shaver to end the PAIS

Infection, neuropraxia, arthrofibrosis, complicated regional pain syndrome, and irritation of the fibular nerve are among the complications.

Post-operative treatment:

Patients are allowed to bear weight as tolerated right away following surgery for posterior ankle impingement, which is treated with a compression bandage. As tolerated, patients may also start flexing their ankles. Early range of motion and weight bearing is intended to prevent post-operative stiffness and, ideally, shorten the time required before returning to sport. Unless individuals have more severe osseous injuries, which may require adjustments to the aforementioned approach, ankle immobilization is typically not required.

Medical Procedures:

- 3 days of no weight bearing (NWB) in boot

- WBAT (weight bearing at the toe) day 3

- NSAIDs and elevation for oedema

- Ankle toe movement

- 10–14 days following surgery, suture removal, and then physical rehabilitation.

Physical Therapy Management:

The goal of treatment is to create greater joint space, which will improve mobility and reduce pain while engaging in physical activity. Despite little evidence of its effectiveness, nonsurgical therapy is still the first line of defence in the management of anterior and posterior impingement syndromes. Resting for a while and staying away from provocative activities are advised for acute symptoms. Modifications to shoes, such as heel lift orthoses to stop dorsiflexion, have been used in chronic cases.

After an ankle inversion sprain, patients should have conservative care for at least six months. Following an ankle inversion injury, they should receive conservative treatment that includes sufficient joint rehabilitation, peroneal strengthening, and muscle balance.[33] Patients who don’t improve with conservative treatment can need surgery.

Physiotherapy for posterior impingement comprises the following:

- Mobilization of the plantar flexion

- Talocrural mobilization in P/A

- Modulation of the rear foot distraction

- Wobble board for proprioceptive work

- Peronei bolstering

- Exercises that are eccentric and isometric help strengthen and stretch the muscles in the lower legs.

- Exercises to strengthen the deep muscles used in plantarflexion. The impact of the Os trigonum on the posterior tibia is lessened during plantarflexion by employing the deep muscles to move the talus forward.

- HEP: Lunge dorsiflexion stretch, single-leg balancing, stretching the Achilles tendon, and increasing the resistance on the ankle

- Dorsiflexion taping for safety

Summary:

An annoying problem that can limit your capacity to perform at the top levels of your sport or activity is posterior ankle impingement. It may be tempting to push through the discomfort in your hindfoot and keep working out, but it’s crucial to pay attention to your body.

A disorder known as posterior ankle impingement syndrome affects the back of the ankle and results in severe, difficult-to-localize pain. Although it can also happen in non-athletes with hindfoot bone anomalies, this problem is more frequently encountered in dancers and players whose sport includes repetitive plantar flexion.

A medical expert’s accurate diagnosis of your discomfort can help you focus on the best course of action and hasten your recovery. While surgery is occasionally necessary, conservative care is often sufficient to let you resume your favorite hobbies.

Many PAIS instances can be successfully treated with conservative therapy, but if the discomfort doesn’t go away, surgery can be required. Typically, a complete physical examination and imaging tests are required to accurately identify this problem.

FAQs:

What is the sensation of posterior ankle impingement?

Deep posterior ankle discomfort brought on by plantar flexion of the ankle joint is the defining feature of PAIS. Although the pain in the hindfoot is reported as constant, severe, dull, and radiating, it is typically difficult for patients to pinpoint its exact position.

Will ankle impingement go away?

Resuming an activity or sport depends on the person, but athletes with straightforward situations can usually do so in four to six weeks. Even though it might take longer for the discomfort to entirely subside, it shouldn’t have an impact on your ability to engage in sport-specific activities prior to your return.

How is posterior impingement tested?

The afflicted shoulder is placed at 90 degrees of abduction, 110 degrees of extension, and maximum external rotation for the posterior impingement test. If the test reproduces the athlete’s shoulder ache, it is successful.

Can physiotherapy help an impinged ankle?

Physical therapy is typically used to treat ankle impingement, but surgery may be necessary if bone spurs develop. Pain management and a range of physical therapy exercises are frequently used as treatments to help the ankle.