Diaphragm Muscle Dysfunction

Table of Contents

What is a Diaphragm Muscle Dysfunction?

The diaphragm muscle is a critical component of the respiratory system, playing a vital role in the process of breathing. As a dome-shaped skeletal muscle, it separates the thoracic and abdominal cavities and contracts and relaxes rhythmically to facilitate inhalation and exhalation. Efficient diaphragm function is essential for maintaining proper ventilation and gas exchange within the lungs.

However, like any other muscle in the body, the diaphragm is susceptible to dysfunction, leading to various respiratory and overall health issues. Diaphragm muscle dysfunction can arise from a range of factors, including injuries, neuromuscular disorders, and certain medical conditions.

Respiratory symptoms, including dyspnea, exercise intolerance, sleep difficulties, hypersomnia, and, in the most severe cases, a detrimental effect on mortality are all linked to diaphragmatic dysfunction.

The primary breathing muscle is the diaphragm. The diaphragm’s dome shape changes very little during quiet inspiration, and the muscular contraction shortens the apposition zone (the region where the lower rib cage and the diaphragm are in direct contact), rising abdominal pressure while lowering pleural pressure, causing the diaphragm to move caudally like a piston.

The coastal wall will tend to collapse as a result of the latter, which is conveyed to the lung and causes it to insufflate. The diaphragm in the lower ribs contracts, opening the thoracic cage, and increasing abdominal pressure causes the thoracic cage to expand in the opposition area, compensating for this action.

What is a Diaphragmatic dysfunction?

Eventration, weakness, and diaphragmatic paralysis are all included in the phrase “diaphragmatic dysfunction.” A persistent elevation of all or a portion of the hemidiaphragm brought on by thinning is known as eventration. Paralysis is the complete lack of this ability, whereas diaphragmatic weakness would indicate the partial loss of muscular strength required to create the appropriate pressure for effective breathing.

Depending on the underlying reason, this disease may be unilateral, bilateral, transient, or permanent.8 The protrusion of abdominal tissue or organ via a diaphragmatic defect is known as a hernia. The Bochdalek and Morgani hernias and the hiatus hernia are the most common congenital hernias. They can be seen as a localized elevation of the diaphragm on a chest X-ray.

Diaphragmatic flutter is another uncommon kind of diaphragmatic dysfunction. The emergence of recurrent, variable-duration bouts of regular involuntary contractions is what defines this disorder. Dyspnea, thoracoabdominal discomfort, and pulsations in the epigastrium are all indications of diaphragmatic flutter. There is currently no accepted standard of therapy for this illness, and its cause is unclear. Several studies have been conducted with various medications, surgical phrenic nerve ablation, and non-invasive ventilatory assistance, with varied degrees of success.

Causes:

Causes that can cause diaphragmatic dysfunction:

- Cerebral cortex:

- Vascular accident

- Central nervous system:

- Multiple sclerosis. mainly it implicates expiratory muscle.

- Spinal cord –

- Traumatic degenerative diseases such as severe spondylosis

- Motor neuron disease:

- Post-polio syndrome

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- Syringomyelia

- Brachial plexus-

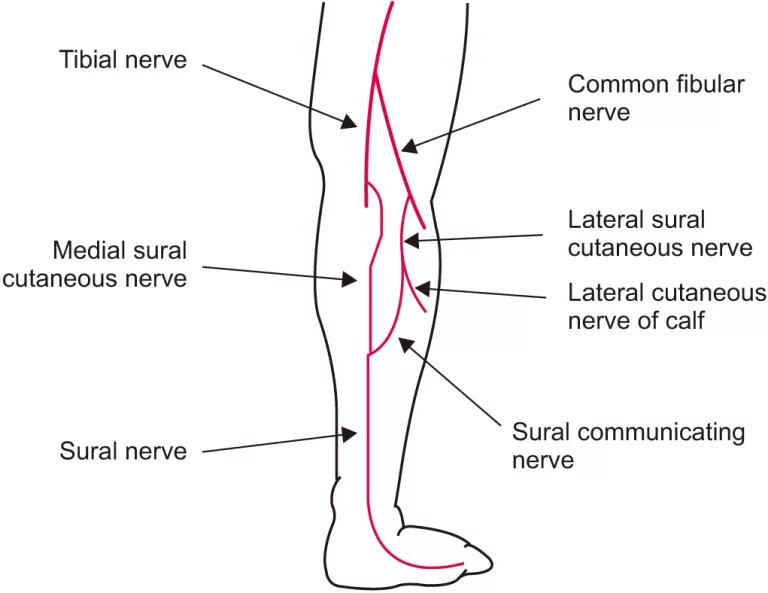

- Phrenic nerve-

- Trauma

- Guillain barre infection: it is the most frequent cause of acute respiratory muscle paralysis.

- Lung-

- Asthma and Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

- Neuromuscular junction-

- Myasthenia gravis

- Botulism

- Muscular-

- Muscular dystrophies

- Myositis

- Mechanical ventilation

- Amyotrophic neuralgia

- Thoracic surgeries

Symptoms of Diaphragm Muscle Dysfunction

Unilateral involvement of the diaphragm:

Unilateral diaphragmatic dysfunction may not present with symptoms, which is why it is frequently discovered by chance when a chest X-ray taken for another cause shows an elevation in the hemidiaphragm. Patients who are obese or who have pulmonary or cardiac pathology in addition to their symptoms typically have more severe symptoms. The most typical signs are:

- Dyspnea with exertion

- Nocturnal hypoventilation and orthopnea

- Oesophageal reflux disease.

Physical examination findings are non-specific:

- Possible dullness to percussion

- Diminished respiratory sounds at the base of the afflicted hemithorax.

- Sometimes when sleeping, thoraco-abdominal motions seem paradoxical.

According to several research, these individuals frequently sleep with the healthy hemidiaphragm in the lower half of the body.

Bilateral involvement of the diaphragm:

Symptoms typically manifest in patients are as:

- Orthopnoea

- Dyspnea, which can happen while at rest, becomes obvious when submerged in water.

- Cyanosis,

- Reduction in breathing noises on both sides,

- When the patient is in the decubitus position, rapid and shallow breathing may occur, as well as the paradoxical movement of the abdominal wall, which is caused by the diaphragm’s “passive” behaviour during inspiration.

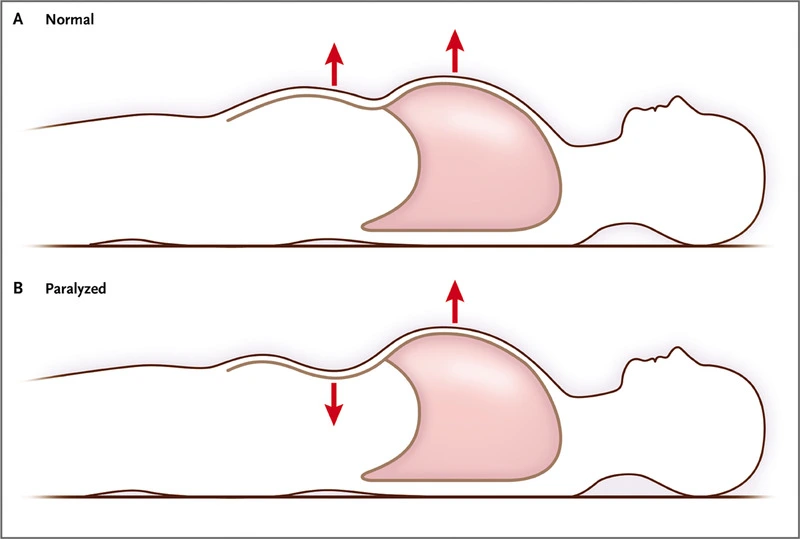

The external intercostal muscles and auxiliary muscles (sternocleidomastoids, scalenes), when contracted when the diaphragm is paralyzed, cause the rib cage to expand and create intrathoracic negative pressure. This allows for inspiration. This pressure will “drag” the abdominal viscera and diaphragm toward the thorax, resulting in a reduction in the anterior abdominal wall and negative abdominal pressure. The majority of individuals with diaphragmatic involvement also have sleep difficulties, severe hypoventilation, particularly during REM sleep, and associated symptoms.

Diagnosis:

A physical examination and discussion of your symptoms will be the first steps in making the diagnosis of a diaphragm condition. Testing could involve:

- X-ray: A chest X-ray can reveal the existence of obstructions or fluids that are exerting pressure.

- CT scan: This test creates fine-grained cross-sectional pictures of your chest cavity by fusing X-ray and computer technologies.

- MRI: Using a powerful magnet, a computer, and radio waves, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) produces precise pictures of organs and other bodily structures. Radiation is not used in MRI, in contrast to computed tomography (CT or CAT) scans or X-rays.

- Ultrasound: To find any anomalies in the diaphragmatic function, this imaging technique catches movement.

- Fluoroscopy: It is a test that enables us to continually see the diaphragm during the course of the typical respiratory cycle as well as when doing forced inhalation manoeuvres. It has been the industry standard for years when it comes to the diagnosis of diaphragmatic paralysis since it is a simple-to-use and interprets technique5 with high interobserver reliability. Fluoroscopy results, however, might be misunderstood in certain patients with bilateral diaphragmatic insufficiency because some individuals may adopt an odd breathing pattern when standing to make up for their immobility. The fluoroscopy may perceive this compensatory mechanism as a diaphragmatic contraction. Some writers advise doing a fluoroscopy when the patient is in the recumbent posture because this circumstance can be avoided. Fluoroscopy is a helpful technique to diagnose unilateral hemidiaphragmatic paralysis because of this. Fluoroscopy, on the other hand, is less helpful for bilateral dysfunction since the results might be interpreted incorrectly. An experienced radiologist should execute it while the patient is upright (frontal and lateral) or in decubitus.

- Pulmonary Function Test: Both standing and laying down pulmonary function tests, including:

- Spirometry: This examination evaluates how much and how quickly you exhale air to determine how much your bronchial tubes are swollen and constricted.

- Peak flow meter: This tool gauges the force of your exhalations. Peak flow meters may be used to keep an eye on your health at home.

- Exercise oximetry: It uses a sensor that is attached to your finger to measure the amount of oxygen in your blood when you exercise.

- A blood test called arterial blood gas examines your blood’s oxygen and carbon dioxide levels as well as its acidity.

- Phrenic Nerve Stimulation Test.: Test to evaluate the reaction of the phrenic nerve using electric or magnetic stimulation of the neck:

- EMG: Using electrical impulses to excite muscle fibres, a test known as electromyography (EMG) evaluates the electrical potential of those fibres.

Treatment of Diaphragm Muscle Dysfunction

The key factors influencing diaphragmatic paralysis therapy are the patient’s symptoms and the underlying causes of the condition. Patients with asymptomatic unilateral involvement often don’t need to be treated. All contributing variables, including obesity, respiratory conditions, and chronic heart problems that may affect and exacerbate paralysis symptoms, must first be addressed.

When the cause of paralysis is recognized and possibly treatable, such as in cases of viral processes, metabolic disorders, endocrinological conditions (such as diabetes or hypothyroidism), or systemic erythematosus lupus (shrinking lung syndrome), there are particular therapies available. We must also keep in mind the possibility of spontaneous resolution in paralyzed idiopathic causes, such as amyotrophic neuralgia. It has been demonstrated in other investigations that diaphragmatic paralysis with a possibly reversible cause (surgical, paraneoplastic, diabetic neuropathy, etc.) might resolve spontaneously over time in 40–60% of patients, suggesting the convenience of deferring any surgical treatment.

The patient may be a part of a specialized respiratory rehabilitation program while under supervision. It has been demonstrated that individuals with diaphragmatic dysfunction benefit from a year of inspiratory muscle training following heart surgery in terms of improving diaphragmatic mobility and inspiratory muscle strength.

Surgical diaphragmatic Plication:

The primary surgical corrective procedure offered to people with diaphragmatic paralysis to manage dyspnea is this one. The paralyzed diaphragm is folded in order to be immobilized in the maximal inspiration position, easing pressures on the lung parenchyma and allowing for lung reexpansion. A thoracic (with thoracoscopy) or abdominal approach can be used. It is primarily recommended for symptomatic patients with unilateral diaphragmatic dysfunction that, according to clinical, radiological, and functional testing, has persisted and is considered irreversible after a period of observation of 6 to 12 months. Additionally, plication has been carried out effectively in certain individuals who had bilateral involvement. The three primary causes of paralysis in the group of patients who underwent surgery were trauma, heart surgery, and iatrogenic.

Plication has been demonstrated to be efficient, safe, and to result in a few problems while improving symptoms and dyspnea. The positive benefits of plication can be shown in enhanced pulmonary function metrics in addition to radiological examinations. Following surgery, improvements are seen in the tidal volume of both hemidiaphragm (the healthy and the operated, likely as a result of a significant improvement in the expansion of the abdominal compartments of the rib cage), exercise capacity, daily activity, and quality of life, with a reduction in score of up to 20 points on the Saint George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. All of this enables several individuals to resume their regular lives. Relative contraindications include morbid obesity, diaphragm calcification, and a few neuromuscular disorders.

Microsurgical restoration of the phrenic nerve

This surgical strategy may be beneficial for patients with unilateral phrenic involvement that is largely iatrogenic or traumatic in origin and who have not shown any clinical or radiological improvement in a fair amount of time, which includes techniques like local decompression, transposition, or interposition of a nerve graft. Through PN conduction investigations and electromyography, it is required to first show the nerve’s continuity and the neuromuscular plate’s viability.

Pacemaker with a diaphragm:

It can be used in patients with reduced bilateral diaphragmatic mobility who want to put off starting invasive or non-invasive ventilation or who have already begun but don’t want to go on or couldn’t handle it. These individuals often have central abnormalities other than cervical involvement, primarily congenital or acquired central hypoventilation, or cervical involvement at a level above C3. Additionally, individuals with lower motor neuron involvement due to causes other than amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, traumatological conditions, or idiopathic causes may exhibit it.

With increased death rates in patients with pacemakers, the most pertinent research on the use of a diaphragmatic pacemaker in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis reported so far has not validated its anticipated advantages. As a result, it is not recommended for this kind of patient at this time. Patients receiving this therapy must be carefully chosen and evaluated at reputable institutes; Confirmation of severe nighttime hypoventilation and demonstration of excellent PN, diaphragm, and lung function is required.

Ventilation assistance:

Both patients with unilateral and bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis have successfully employed it, either permanently in the latter case or temporarily in the former up until full diaphragmatic function was restored. Positive pressure ventilation (NPPV) or intrusive mechanical ventilation can both be used to provide ventilation support. Generally speaking, symptomatic individuals with bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis are treated well with NPPV. It has been demonstrated that long-term improvement in clinical and blood gas parameters may be achieved through tolerance. Similar signs for other neuromuscular or restrictive disorders would apply to non-invasive breathing.

Due to the paralysis of the respiratory muscles, patients with acute respiratory failure may require intubation and mechanical ventilation, which might last for some time. Early tracheostomy shortens the duration of invasive ventilation and length of stay in the intensive care unit, and it also lowers the incidence of complications related to orotracheal intubation, with the exception of ventilation-associated pneumonia, according to a study of 152 patients with spinal cord injury, 50% of whom had affectation at the C3-C5 level. Non-invasive ventilation, however, has been suggested as a weaning technique before tracheostomy in cooperative patients with bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis, a limited volume of secretions, and a suitable inspiratory flow.

When non-invasive ventilation has failed or invasive therapies are unsuccessful, individuals with neuromuscular diseases may also need a tracheostomy and invasive ventilation.

There are various difficulties with non-invasive ventilation. The usage of masks might cause minor or temporary difficulties. Strict patient selection and ventilation control can reduce the risk of severe complications from:

(1) Ventilation failure;

(2) Ventilation-associated pneumonia;

(3) Barotraumas; and

(4) Hypotension.

Patients on invasive ventilation are at a lower risk of these complications than those not receiving them.

Summary:

In conclusion, diaphragmatic dysfunction may have significant clinical repercussions. Its cause must be determined, and its symptoms, impact on sleep architecture, and ability to engage in activity must be treated. Ultrasound is a quick and efficient way to regularly check diaphragm function, which helps doctors decide on the best course of treatment. Diaphragmatic dysfunctions should be addressed at facilities with experience, access to phrenic stimulation, pacemaker implantation, and surgical expertise in diaphragmatic plication.

FAQs:

Disease processes in the central nervous system, the phrenic nerves, the neuromuscular junction, or anatomically may cause diaphragmatic dysfunction. One or both hemidiaphragm may be affected by dysfunction, which can range in severity from a partial lack of muscle contraction to full paralysis.

Management / Treatment

In some circumstances, a chest tube should be put to treat an accompanying hemothorax or pneumothorax. The tube should be carefully positioned to prevent inflicting more harm. Since diaphragm injuries can not heal on their own, practically all patients need surgery to be repaired.

As your stomach starts to push outward against your palm, take a slow, nasal breath. As quietly as you can, keep the hand there on your chest. As you exhale through pursed lips, contract your abdominal muscles to cause your stomach to move back in. You must keep the hand on your upper chest as motionless as you can.

The most frequent cause of diaphragm weakness brought on by medical intervention is physical injury to the phrenic nerves or diaphragm muscle. Examples that are well-known include the use of ice slush during cardiothoracic surgery, head and neck surgery, central venous catheterization, and neuropraxia.

The diaphragm is a sheet of muscle that lies behind the lungs, and the muscles between the ribs regulate the movement of the lungs. A person’s breathing rhythm alters while they are under stress.