Skin

Table of Contents

Overview

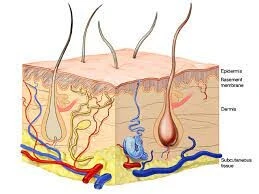

The skin, the most significant organ in the body, regulates body temperature, generates tactile sensations, and works as a barrier against viruses. The epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis are the three major layers of skin, and they are at risk of several kinds of conditions such as rashes, wrinkles, acne, and skin cancer.

The most important organ in the body, the skin comprises a mixture of water, protein, lipids, and minerals. The skin has nerves that perceive heat and cold.

The integumentary (in-TEG-you-MEINT-a-ree) system incorporates your skin, hair, nails, sweat glands, and oil glands. “Integumentary” signifies a body’s uppermost layer.

Structure

The skin includes three distinct layers.

- The epidermis, the outermost layer of the skin, generates a waterproof barrier and controls skin tone.

- Constantly situated underlying the epidermis, the dermis is a structure formed of blood arteries, which carry glands that produce sweat, hair follicles, vessels for lymphatic drainage, and connective tissue.

- Adipose and fibrous tissue are elements of the deeper under-the-skin layer, or layer according to the skin.

Epidermis

The epidermis is divided into:

- Four layers in alternate locations (in the absence of the stratum lucidum)

- Per where it is positioned the epidermis has 4 to 5 phases of stratification.

The corneum layer, stratum lucidum, stratum drifting substances, stratum spinosum, and the bottom layer are five different layers that form up the thick skin of the fingers and toes.

- Stratum Basalis (Basal cell layer): Melanocytes, which supply the skin its color, have immunologic cells such as T and Langerhans cells, and basal keratinocytes constituents of the stratum basale. Keratinocytes from this layer develop and mature as they move outward/upward and create the subsequent layers.

- Stratum Spinosum (Prickle cell layer): This layer represents most of the epidermis which is made up of several layers of cells accompanied by desmosomes, which keep cells tightly attached and resemble “spines”.

- Stratum Granulosum (Granular cell layer): This layer is composed of granules with a composition rich in lipids and consists of an array of cell types. As the cells in this layer relocate towards the nutrients located in deeper tissue, they start releasing their nuclei and remain immortal. The stratum granulosum of keratinocytes holds histidine-containing and cysteine-rich granules that keep the keratin threads together.

- Stratum Lucidum: It is a thin, transparent coating formed from dead keratinocytes. The stratum lucidum is visible given that keratinocytes in this layer release eleidin, which is an intracellular protein, that holds on of keratin.

- Stratum Corneum (Keratin layer): It is the leading edge of the epidermal. In addition to its lipid content and keratinization, this keratinized layer functions as a protective overcoat and prevents water loss by decreasing internal fluid absorption.

Dermis

The dermis is set deep inside the epidermis. Collagen and elastin, which contribute to the thick layer of connective tissue, give the skin its rigidity and pliability, alternately. Blood vessels, nerve endings, and adnexal structures—including sweat glands, skin glands, and hair shafts—are all involved in the process.

The dermis separates into two layers.

- Papillary dermis (the upper layer): The papillary dermis appears while the apical layer of the dermis folds creating papillae, which extend into the epidermis like inadequate finger-like projections. It has capillaries that aid in the diffusion of nutrients.

- Reticular dermis (the lower layer): It has been determined that the dermis with reticular borders is the dermis’s thickest layer. The elevated concentration of collagenous and reticular fibers connected within this layer causes the reticular dermis to be greatly thicker than the papillary dermis.

Both dermal layers are formed up of fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, and immune cells such as macrophages, lymphocytes, and mast cells. To provide dermis structural integrity, fibroblasts synthesize an extracellular matrix consisting of collagen, proteoglycans, and elastic fibers.

Hypodermis

- The third and innermost layer, the hypodermis, essentially consists of adipose tissue.

- Adipose tissue in the skin operates as an endocrine organ that maintains lipid metabolism and glucose homeostasis. It additionally preserves calories in the form of saturated fats.

- This layer is composed of fibrocytes and adipocytes and is rich in proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans, which give the layer mucus-like characteristics. This layer is inhabited by several immune cells and also includes various kinds of mediators, including cytokines, a group of hormones,s, and growth factors.

- Subcutaneous fat provides an insulating layer for the body when fat is a poor heat conductor.

Physiological Factors

Thickness of Skin

- It differs contingent on geography, age, gender, drugs, and health, all of which affect the density and thickness of the skin. As previously mentioned, the effect of thickness is related to changes in the dermis and epidermis. The stratum lucidum layer and elevated keratinization provide the palms and sole their thick skin, but the eyelids, axillae, and genitalia, as well as mucosal surfaces exposed to the skin, are thinner in surrounding regions, particularly the oral mucosa, vaginal canal, and other specialized indoor body surfaces.

- The loss of ground substance, elastic fibers, and epithelial organs, among other changes in the dermis, is the main cause of the skin’s thinning across the second half of life.

- Natural skin influence can be affected by genetics. In addition, compared to those of Anglo-Saxon ancestry, African Americans typically exhibit thicker, brighter skin.

- External factors also have a direct effect on skin width. In particular, compared to those who work indoors, those whose duties require them to spend a lot of time outside in the sun and UV radiation start showing the symptoms of premature skin aging earlier.

Innervation

- The receptors that assess touch (low-threshold receptors), temperature (temperature receptors), pain (insomniacs), and itching (preceptors) are formed by neurons in the senses that innervate the skin. There are neuron-free ends that include these receptors.

The free nerve endings of nociceptive nerves originate at various portions of the epidermis, positioning them near hair follicles and epithelial cells.

Merkel cells are oval-shaped cells located around the basal layer of the epidermis and innervated by sensory fibers; they are involved in mechanosensation or light touch. Pacinian corpuscles are sensitive to vibration and pressure; they occur in the reticular dermis. The Aα and Aβ sensory nerve fibers placed in the sensory ganglia present a pair of corpuscles.

The development of thermoreceptors, which are important for detecting temperature variations between the skin and the air around it, is found on both heat- and cold-sensitive nerves, with the skin having an elevated amount of cold-sensitive nerves. Vasodilation, vasoconstriction, sweating, and shivering are caused by the activation of thermally sensitive nerves when reacting to either heat or cold.

2. The skin carries corpuscles that are habitat to supplementary mechanoreceptors.

3. The articular nerves and dorsal root ganglia form the cell sections of the nerves supplying the skin.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

- The cutaneous plexuses found between the reticular and papillary layers nourish the skin, which is highly vascularized.

- Larger blood arteries and capillaries that correctly branch off of microscopic branches of the systemic circulation that reach particular portions of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue are the primary sources of the blood supply.

- An extensive lymphatic system connects many of the blood veins in the skin, particularly those that join to the venous end of the capillary structures.

Muscles

Every region of the skin possessing hair roots has the director-supporting muscles, they are the weakest muscles found in the body. These muscles adjust to surrounding indicators, such as heat and erosion, by altering hair growth length and sebaceous gland activity. When the sympathetic nervous system is active, as it is during the reaction to flee or fight, the arrector pili muscles contract and the hairs stand up in stressful situations.

Functions of the Skin

- Protection: Protection against UV rays, bacteria, mechanical harm, and dehydration. The skin functions as the body’s initial initial resistance against the elements of the external world.

- Sensation: pain, temperature, touch, and deep pressure.

- Mobility: enables the body to move smoothly.

- Endocrine Activity: The biological mechanisms creating vitamin D, which is required for calcium absorption and healthy bone metabolism, are initiated by the skin.

- Exocrine Activity: Despite secreting chemicals like perspiration, pheromones, and sebum, skin also secretes bioactive molecules like cytokines, which have a significant impact on immunologic systems.

- Immunity: development of defenses against infections.

- Temperature Regulation: Apart from regulating the circulatory system and homeostatic balance, the skin helps control the body’s temperatures by taking in and expelling heat.

Clinical Relevance

Skin Pigmentation

The skin’s modifications are assisted by the pigmentation particle. It supplies the organism with photo-protection by absorbing UV rays from the Sun.

- White Colour – Lack of Melanic Pigment

- Black Colour – Increased Melanin Density

The ratio of the two different kinds of melanic pigments, eumelanin and pheomelanin, creates the distinctions in human skin shading.

- Skin that is lighter in color and more susceptible to sunburns is connected with higher levels of polyphenol melanin instead of eumelanin.

Studies reveal that skin with higher levels of pheomelanin is more likely to suffer from cancer after being struck by UV radiation from the sun. This is because larger levels of reactive oxygen species appear, which can cause cellular lesions and trigger the carcinogen process.

Skin Response in Wound Healing

Hemostasis, inflammation, cellular proliferation, and remodeling are the four key phases of wound healing.

- Any change in any of the periods of wound healing leads to impaired healing.

- Long-term inflammation is linked to insufficient wound healing and constant wounds.

- The disruptions in the proliferative and remodeling phase can result in fibrosis, scarring, and disparate wound closure.

Common Non-healing Chronic Wounds

The most commonly chronic wounds that cannot be recovered are diabetic wounds, pressure ulcers, venous stasis ulcers, and arterial stasis ulcers.

Burns

- The epithelium layer of the skin becomes infected in first-degree burns.

- Second-degree, which affects the dermis,

- The skin becomes impacted by third-degree impairment.

Burn injuries are defined by edema and a period of serious swelling. In addition, blistering often happens in second-degree burn patients. Patients with severe burns tend to develop a range of systemic problems, including decreased or heightened immune responses, electrolyte imbalance, sepsis, and syndromes involving multiple organ failure. Patients with severe burns also frequently suffer emotional impacts attributed to inflammation.

Wound Complications

Infections

Infections locally or systemically could occur from impaired wound healing.

The environment underlying non-healing wounds is characterized by malfunctioning immune responses, which make it easier for pathogenic germs to colonize the injured tissue. Biofilms are single- or multi-strain colonies of microorganisms that are frequently accomplished in wounds that do not heal. Antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains, including pathogenic strains of S. epidermidis, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, and S. aureus, have been connected with diabetic wounds.

Common bacterial infections affect burn victims; Acinetobacter baumanii, S. aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Klebsiella pneumoniae are the most recurrent strains. Numerous strains can build biofilms, which can cause bacteremia and sepsis if the infections continue.

Nerve Damage

Nerve injury usually comes as the result of deep skin wounds. Individuals enduring nerve damage endure numbness, discomfort, and a partial or entire loss of motor or sensory function in the affected area.

- When anybody is cut, a nerve might get transected.

- Burn injuries, specifically those classified as third-degree, cause nerve damage that leaves the affected area without any kind of feeling.

Hypertrophic Scarring and Keloids

It is the consequence of fibroblasts in the wound bed producing a large quantity of collagen. Burns and other cutaneous traumas affecting the skin’s dermal layer might end up in hypertrophic scarring.

Skin Microbiome

Beneficial bacteria colonize the skin, acting as a physical barrier that inhibits pathogen invasion. The breakdown of natural products, immune system education, and protection against incurable infections are all greatly aided by the microorganisms on our skin.

By battling for breathing space, they shield the host against an attack of the skin by pathogenic microorganisms. Commensal strains can secrete antimicrobial compounds like bacteriocins, which stop harmful bacterial strains from growing. Low commensal strains are normally linked to pathogenic strains occupying the skin.

In comparison to the bacterial kingdom, which is more diverse than the fungal infections kingdom, the viral microbiome is uncertain and has a smaller range than the fungal species.

Skin as an Immune Organ

The viral microbiome is uncertain and doesn’t show as much diversity as the bacterial kingdom, although it does exhibit more diversity than the fungal infections kingdom.

- Each corneocyte has an internal compartment filled with keratin filament bundles connected to a lipid envelope, which causes the corneocyte more stiffer.

- The three layers that constitute the stratum corneum perform as an outside-in barrier against the penetration of organisms and foreign items and an inside-out barrier to inhibit water loss.

- The epidermal layers’ tight junction proteins (Claudin-1/zonula occludins-1) and junction adhesion molecules promote the physical barrier’s creation.

Skin pH

The SC and the underlying epidermis and dermis are defined by a gradient of two to three units. According to a recent study, the formation and ongoing maintenance of a functional skin barrier depend on several important enzymes, including skin pH.

Several kinds of antimicrobial peptides created by sweat glands inhibit the growth of different microorganisms on the skin. Sweat glands release dermcidin, an antibacterial peptide, onto the skin’s epidermal surface during intensive physical activity. According to research, sweat that is somewhat acidic and salty activates dermcidin, which may enter the membranes of microorganisms and cause water and charged zinc to circulate beyond the cell membrane and kill the microbe.

In addition, commensal bacteria like Staphylococcus epidermidis gain from the natural pH of the skin, which helps to stop pathogenic strains like Staphylococcus aureus from infecting the host.

Immune and Non-immune Cells

Immune cells found in the skin actively examine environmental antigens to protect the body and support tissue function in homeostasis.

Skin and Circadian Rhythm

The skin functions as an original connection between the body and its surroundings, absorbing light-related impulses and producing them. Peripheral clocks are found in skin cells. A rising number of studies are being done on circadian and ultradian (an oscillation that occurs more than once in a day) cutaneous rhythms.

This research includes clock mechanisms, functional manifestations, and stimuli that either synchronize or desynchronize the natural cycle. The circadian rhythm has therapeutic and harmful effects on both skin health and illness. This affects different systems and is indirectly mediated by hormones and neurons. The skin has an active circadian rhythm that is monitored by the central clock.

Skin Conditions

Psoriasis

The most common sign of lesional psoriatic skin is epidermal hyperplasia, which is caused by an excessive amount of reproducing keratinocytes and inflammation in psoriasis, a chronic inflammatory skin condition. The elbows, knees, and scalp are the areas where psoriatic plaques are most frequently.

Acne

The skin on the face, upper chest, and back with a significant level of sebaceous follicles is frequently impacted by acne vulgaris, most generally referred to as facial acne. Increased P. acne anaerobic bacterial colonization, increased sebum production from the sebaceous glands, autoimmune diseases, and hyperkeratinization are its most significant features.

Atopic Dermatitis

Eczema and itching are typical indicators of atopic dermatitis, a persistent inflammatory skin infection. Atopic dermatitis can be impacted by immunological, environmental, and genetic conditions.

FAQs

What is the primary function of the skin?

The skin is the biggest and primary organ for protection in that it covers the entire body’s appearance and operates as an initial-order physical wall versus the environment.

What type of skin is it?

In accordance with the American Association of Dermatology (AAD), all five general varieties of skin are normal, entirety, oily, dry, and sensitive. Anyone of these skin types has special needs and aspects that can affect how your complexion feels and looks.

What role does skin play a role?

Defends and secures you. Tackles harmful bacteria and prevents them from entering the body. Produces melanin, the pigment that gives skin its color and aids in preserving the skin from UV rays that harm it. Aids to preserve the proper body temperature.

What is the skin’s structure?

The epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis are those three core layers that constitute the skin. It consists of the following things: The first cells of the epidermis created by cell division at its base are called keratinocytes.

References

- Skin layers: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia Image. (n.d.). https://medlineplus.gov/ency/imagepages/8912.htm

- Professional, C. C. M. (2024d, June 27). Skin. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/10978-skin

- Yousef, H., Alhajj, M., Fakoya, A. O., & Sharma, S. (2024, June 8). Anatomy, Skin (Integument), Epidermis. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470464/