Human mouth

Table of Contents

Overview

In human anatomy, the mouth is the first portion of the intestinal tract that helps consume food and release saliva. The oral mucosa is another name for the layer of mucous epithelium situated inside the mouth. The mouth contributes as the digestive system‘s initial step and serves as an important for interaction. The jaw, lips, and tongue are also important to produce the broad range of sounds that make up speech, however, the throat produces the majority of the voice.

The nostrils and the mouth’s interior are the identical components of the mouth. The teeth belong in the mouth, which is protected by mucous membranes and is frequently swollen. The skin, which covers a significant portion of the body, is visible through the mucous membrane of the lips.

Structure of Mouth

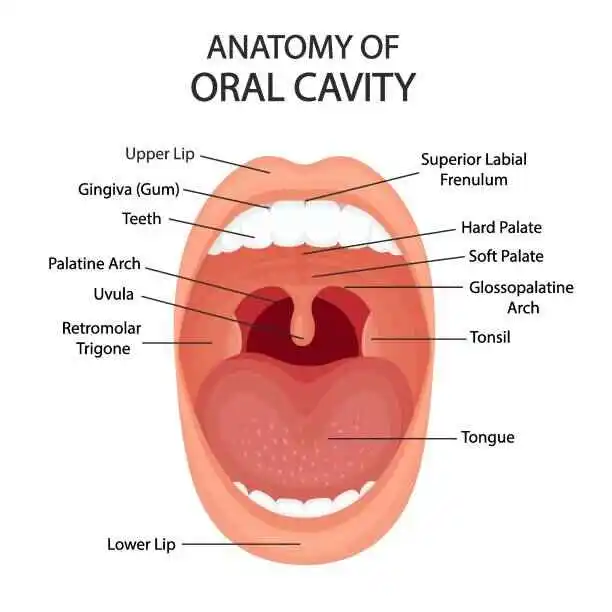

Oral cavity

The septum and the internal structure of the mouth are the two components that compose the mouth. The vestibule is a region around the teeth, lips, and cheeks. Despite the isthmus of the fauces covering it on the inside, the alveolar system particularly utilizes the teeth to detect the oral cavity on the sides and front.

The firm palate covers its roof. The anterior two-thirds of the tongue properly exists on the floor, which involves the building up of the mylohyoid muscles. From the outer edge of the tongue to the gums and within the cavity of the jaw (mandible), it’s a mucous membrane known as the oral mucosa. It releases secretions from the sublingual and submandibular salivary glands.

The posterior boundary of the oral cavity, or the point where the oral cavity and the oropharynx survive, can be determined by the retromolar trigone, the circumvallate papillae of the tongue inferiorly, and the intersection of the hard and soft palates superiorly.

Lips

when the roof and lower lips press together to shut the mouth’s opening, an expression is formed. In the context of facial expression, this mouth line is visible as a down-open parabola in a frown and an up-open parabola in a smile. When a mouth line forms a downturned parabola, it signifies a permanent downturned mouth, resulting in what should be classified as normal. The Prader-Willi syndrome might show up as a downturned mouth.

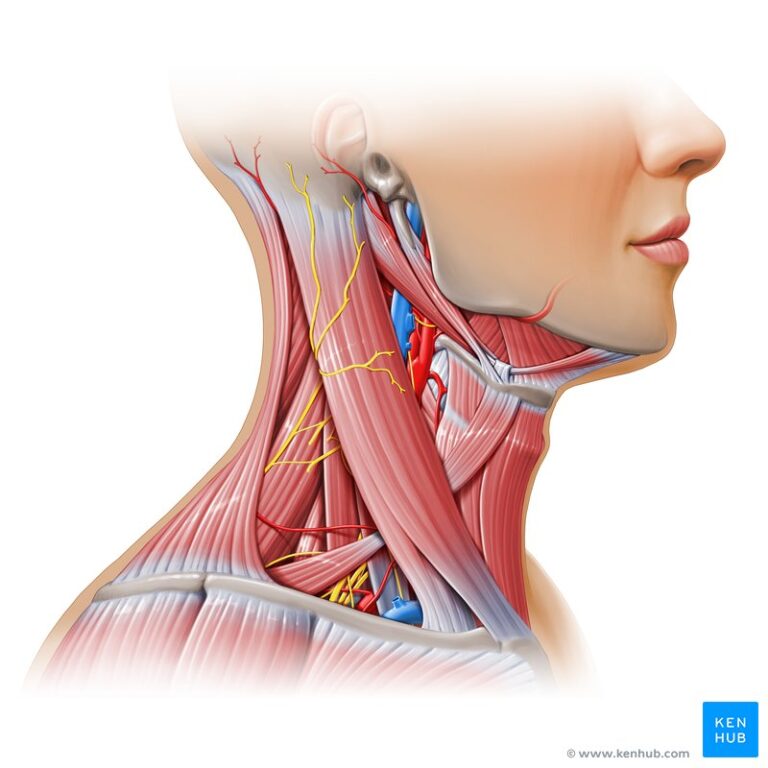

Nerve supply

The superior alveolar nerves, which regulate the maxillary (upper) teeth, can be found in the maxillary compartment. The nerves indicated below are the anterior superior oral nerve, the posterior superior maxillary nerve, and the rear superior maxillary nerve. the periodontal ligament that protects them.

These nerves over the maxillary teeth produce the anterior dental plexus. The inferior alveolar nerve, a branch of the mandibular division, binds the periodontal ligament that supports the mandibular (lower) teeth. This nerve generates branches to per lower jaw (inferior dental plexus) after crossing up the inferior alveolar canal situated between the mandibular teeth inside the jaw. The superior labial segments of the infraorbital nerve on the face (labial) sides of the maxillary communicate the brain to the oral mucosa of the gingiva (gums). incisors, canines, and premolar teeth.

The posterior superior alveolar nerve distributes gum tissue on the exterior aspect of the maxillary molar teeth. The greater palatine nerve hooks to the enamel on the palatal parts of the maxillary teeth, although the nasopalatine nerve (long sphenopalatine nerve) stimulates the gingiva in the incisor of the hole. The sublingual nerve, a branch of the lingual nerve, maintains the tissue known as gingiva, which is found on the lingual surface of the mandibular teeth.

The mental nerve innervates the gingiva on the visage facet of the mandibular incisors and canines, connecting the inferior alveolar nerve that develops from the mental foramen. The buccal nerve, which is additionally known as the long mandibular nerve, and the fibrous tissues of the mandibular (lips) portion interact in mandibular molar teeth.

Development

Where the nasomedial and maxillary processes are fulfilled during embryonic development, an angled depression known as the philtrum appears between the philtral ridges across the nasal septum and the upper lip. There may be a cleft lip, cleft palate, or both if these processes don’t adequately fuse.

The deep tissue wrinkles radiating from the nose to the sides of the mouth are called nasolabial folds. The nasolabial folds’ increasing visibility is one of the earliest indications of aging on the human face.

Function of Mouth

Speaking, eating, and drinking all involve the mouth. Mouth breathing is the method of breathing through the mouth (as a temporary backup selection) once breathing through the nose, the body’s designated respiratory organ, is restricted.

Babies are born with a sucking reflex, which means they know to use their jaw and lips to suck for food. Further, the mouth facilitates biting and eating food.

When typing, texting, writing, or creating drawings, paintings, or other artwork by using brushes and other tools, some disabled people—especially many disabled artists—use their mouths in place of their hands as their bodies have lost dexterity due to illness, accidents, or congenital disabilities.

Anatomy

Your mouth’s anatomy is constructed of multiple sections. Together, the above elements facilitate speech, breathing, and chewing. The border created on the outside of your mouth helps you constitute sounds and words while also preserving food in place. It covers your jowls and lips.

Your mouth’s inside includes your:

- Teeth.

- Gums.

- Palate (roof of your mouth).

- Oral mucosa (mucus membranes).

- Salivary glands.

- Tongue.

- Taste buds.

- vestibule

The vestibule: The region involving the surface of the skin (mouth and cheekbones), tissues, and tooth enamel. Positioned at the angle of the jaw and in front of the ears, the parotid sweat glands supply the vestibule with the liquids required to stay moist.

Mouth cavity: Multiple structures cover the mouth cavity. The alveolar arches, which are bony structures that protect the teeth, cover the mouth cavity on each of the front and sides. The hard and soft palates are situated beyond the tongue. The mouth cavity retains its moisturized by secretions from the submaxillary and ventral salivary glands, which exist on the floor of the mouth beneath the tongue.

Gums: Consisting of bulky, fibrous cells, they wrap the alveolar arches and cover the teeth.

Teeth: By the time they are three years old, the typical youngster has all twenty of their primary (also known as milk or baby) teeth. Between the ages of six and seven, the primary teeth begin to fall out, and permanent (also known as secondary or adult) teeth progressively replace them.

Palate: Includes both the soft and hard palates. A “hard palate” is a word applied to indicate the skeletal surface of the mouth. The upper layer of the throat and the oral cavity are attached by a membrane curve considered the soft palate. The uvula is the tiny, dangling portion that is visible when you push out your tongue and utter “ah.”

Tongue: A majority of the tongue is made up of muscle fibers. It consists of an oral segment (front, central, back, tip, and blade) and a pharyngeal (throat) section. Conversation, swallowing, and taste are all improved quickly by the tongue.

Minor salivary glands: create saliva, which is the watery fluid that keeps the mouth clean and provides enzymes to help absorb the nutrients of meals. The inner cheeks are one of the several places associated with the mouth where these glands can be found.

Oral mucosa: The inner lining of the mouth is a mucous membrane called the oral mucosa, which is generated up of stratified squamous epithelium. To lubricate and maintain the moisture levels of the oral cavity, several submandibular and sublingual salivary glands release a viscous and mucoid fluid.

Taste buds: The papillae, microscopic cells placed on the upper layer of the tongue, soft palate, upper throat, upper cheek, and epiglottis, are the origins of taste receptors.

Conditions and Disorders

The following general conditions might influence your mouth:

- Bad breath (halitosis).

- Dry mouth (xerostomia).

- Infection.

- Dental injuries.

Other conditions might impact individual oral regions:

Teeth

- Dental plaque.

- Tartar.

- Cavities.

- Abscessed tooth.

- Impacted wisdom teeth.

Gums

- Periodontal (gum) disease.

- Gingivitis.

- Pregnancy gingivitis.

- Periodontitis.

- Gum recession.

- Bleeding gums.

- Swollen gums.

- Trench mouth.

Palate (roof of mouth)

- Cleft lip and palate.

- Submucous cleft palate.

- Torus palatinus (palatal tori).

Soft tissues (oral mucosa)

- Mouth sore.

- Mouth ulcer.

- Canker sores.

- Cold sores.

- Oral lichen planus.

- Erythroplakia.

- Leukoplakia.

Salivary glands

- Sialadenitis (swollen salivary gland).

- Sialolithiasis (salivary gland stones).

- Parotitis (swollen parotid gland).

- Pleomorphic adenoma.

- Mumps.

Tongue

- Tongue-tie.

- Macroglossia (enlarged tongue).

- Glossitis (inflamed tongue).

- Geographic tongue.

- Yellow tongue.

- White tongue.

- Black hairy tongue.

- Spots on the tongue.

- Burned tongue.

Taste buds

- Swollen taste bud.

- Hypergeusia (increased sense of taste).

- Hypogeusia (decreased sense of taste).

- Dysgeusia (taste distortion).

- Ageusia (loss of sense of taste).

- Phantom taste disorder (lingering, unpleasant taste).

Cancerous conditions of the mouth

Any part of your mouth could be suffering from oral cancer. Conditions that result in cancer in the mouth include:

- Oral cancer.

- Lip cancer.

- Head and neck cancer.

- Verrucous carcinoma.

- Salivary gland cancer.

- Buccal mucosa cancer (inner cheek cancer).

- Hard palate cancer.

FAQs

What is the mouth’s primary function?

The mouth is elongated in the skull which has an oval structure. The tongue, salivary glands, hard and soft palates, lips, vestibule, mouth cavity, gums, and teeth form part of the oral anatomy.

How does the respiratory system interact with the mouth?

Your mouth acts as where air penetrates your lungs, equivalent to your nose. Your mouth pulls in more air since it is larger than your nose. Your body can use the air more efficiently because it doesn’t have to go as far.

Does the reason provided by your mouth have significance?

Furthermore, early detection and treatment of problems with dentistry improve better oral health. Sustaining good dental health minimizes the risk of diabetes, heart disease, cancer, and long-term respiratory conditions.

Mouth saliva: what is it?

Your salivary glands secrete a watery liquid into your mouth that is recognized as saliva (spit). Saliva fulfills many kinds of uses, including keeping your teeth and assisting digestion. Mostly formed from water, it also includes diverse other chemicals and numerous essential proteins.

How does the oral system function?

Inside the oral cavity, chewing activates the gastrointestinal process. Saliva is a digestive juice created by your salivary glands that permits food to pass more smoothly down your esophagus and into your stomach by moistening it. Also, saliva contains an enzyme that starts decomposing carbs in the diet.

What role does the mouth perform in speech?

The formation of words comprises the movements of the lips, tongue, and teeth in great detail. To produce all the sounds produced by talking, we adjust the positioning of our lips and tongue, position our teeth, and move the air in various directions.

References

- Department of Health & Human Services. (n.d.). Mouth. Better Health Channel. https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/mouth

- Professional, C. C. M. (2024, May 1). Mouth. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/21765-mouth

- Human mouth. (2024, September 16). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_mouth

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2024, September 30). Mouth | Definition, Anatomy, & Function. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/mouth-anatomy

One Comment