Juvenile arthritis

Juvenile arthritis (JA) is not a disease in itself. Also known as pediatric rheumatic disease, JA is an umbrella term used to describe the many autoimmune and inflammatory conditions or pediatric rheumatic diseases that can develop in children under the age of 16. Juvenile arthritis affects nearly 300,000 children in the United States.

Although the various types of juvenile arthritis share many common symptoms, like pain, joint swelling, redness and warmth, each type of JA is distinct and has its own special concerns and symptoms. Some types of juvenile arthritis affect the musculoskeletal system, but joint symptoms may be minor or nonexistent. Juvenile arthritis can also involve the eyes, skin, muscles and gastrointestinal tract.

Table of Contents

What is juvenile arthritis?

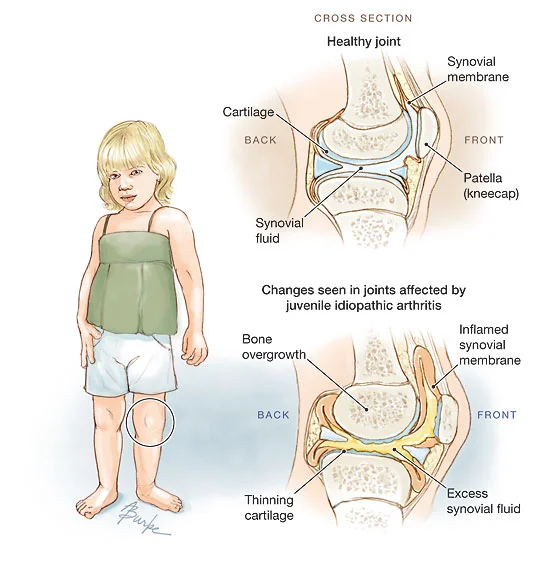

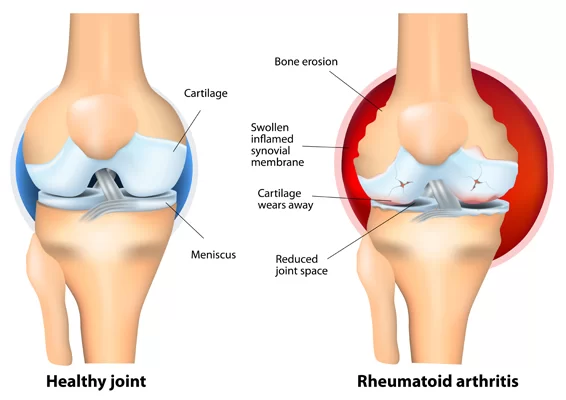

Juvenile arthritis is a disease in which there is inflammation (swelling) of the synovium in children aged 16 or younger. The synovium is the tissue that lines the inside of joints.

Juvenile arthritis is an autoimmune disease. That means the immune system, which normally protects the body from foreign substances, attacks the body instead. The disease is also idiopathic, which means that no exact cause is known. Researchers believe juvenile arthritis may be related to genetics, certain infections, and environmental triggers.

Types of Juvenile Arthritis

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). Considered the most common form of arthritis, JIA includes six subtypes: oligoarthritis, polyarthritis, systemic, enthesitis-related, juvenile psoriatic arthritis, or undifferentiated.

Juvenile dermatomyositis. An inflammatory disease, juvenile dermatomyositis causes muscle weakness and a skin rash on the eyelids and knuckles.

Juvenile lupus. Lupus is an autoimmune disease. The most common form is systemic lupus erythematosus, or SLE. Lupus can affect the joints, skin, kidneys, blood, and other areas of the body.

Juvenile scleroderma. Scleroderma, which literally means “hard skin,” describes a group of conditions that causes the skin to tighten and harden.

Kawasaki disease. This disease causes blood-vessel inflammation that can lead to heart complications.

Mixed connective tissue disease. This disease may include features of arthritis, lupus dermatomyositis, and scleroderma, and is associated with very high levels of a particular antinuclear antibody called anti-RNP.

Fibromyalgia. This chronic pain syndrome is an arthritis-related condition, which can cause stiffness and aching, along with fatigue, disrupted sleep, and other symptoms. More common in girls, fibromyalgia is seldom diagnosed before puberty.

What are the different types of juvenile arthritis?

There are five types of juvenile arthritis:

Systemic arthritis, also called Still’s disease, can affect the entire body or involve many systems of the body. Systemic juvenile arthritis usually causes a high fever and a rash. The rash is usually on the trunk, arms, and legs. Systemic juvenile arthritis can also affect internal organs, such as the heart, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes, but usually not the eyes. Boys and girls are equally affected.

Oligoarthritis, also called pauciarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, affects fewer than five joints in the first six months that the child has the disease. The joints most commonly affected are the knee, ankle, and wrist. Oligoarthritis can affect the eye, most often the iris. This is known as uveitis, iridocyclitis, or iritis. This type of arthritis is more common in girls than in boys, and many children will outgrow this disease by the time they become adults.

Polyarthritis, also called polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (pJIA), involves five or more joints in the first six months of the disease — often the same joints on each side of the body. This type of arthritis can affect the joints in the jaw and neck as well as those in the hands and feet. This type also is also more common in girls than in boys and more closely resembles the adult form.

Psoriatic arthritis affects children who have both arthritis and the skin disorder psoriasis. The child might get either psoriasis or arthritis years before developing the other part of the disease. Children with this type of arthritis often have pitted fingernails.

Enthesitis-related arthritis is a type of arthritis that often afflicts the spine, hips, eyes, and entheses (the places where tendons attach to bones). This type of arthritis occurs mainly in boys older than 8 years of age. There is often a family history of arthritis of the back (called ankylosing spondylitis) among the child’s male relatives.

Fast Facts

Arthritis in children is treatable. It is important to seek treatment from healthcare professionals who are knowledgeable about childhood arthritis.

In spite of their diagnosis, most children with arthritis can expect to live normal lives.

Some children with JIA have their disease go into remission.

Federal and state programs may provide assistance with school accommodations or services. Ask the rheumatology team about summer camps and opportunities to meet other children with arthritis.

Except in rare circumstances, this condition is not directly inherited from the mother or father.

Cause

No one knows exactly what causes juvenile arthritis. Researchers believe some children have genes that make them more likely to get the disease. Exposure to something in the environment (for example, a virus) triggers juvenile arthritis in these children. Juvenile arthritis is not hereditary, so it is very rare for more than one child in a family to get it.

Symptoms

Juvenile arthritis affects each child differently and can last for indefinite periods of time. There may be times when symptoms improve or disappear (remissions). There are other times when symptoms worsen (flare-ups). Sometimes, a child may have one or two flare-ups and never have symptoms again. Other children may have frequent flare-ups and symptoms that never go away.

The most common symptoms of juvenile arthritis include:

Painful joints in the morning that improve by afternoon. Sometimes, the first sign of the disease is a morning limp, caused by an affected knee. Hands and feet may also be affected.

Joint swelling and pain may also be noted. Although young children may not complain of pain, a child may feel irritable or tired and not want to play. Sometimes, juvenile arthritis causes lymph node swelling in the neck and other parts of the body.

Joints may become inflamed and warm to the touch. In fewer than half of cases of juvenile arthritis, internal organs may become inflamed.

Muscles and other soft tissues around the joint may weaken.

In certain cases, children have a high fever and light pink rash, which may disappear very quickly.

Some children develop growth problems. Joints may grow too fast or too slowly, unevenly, or to one side. This can make one leg or arm longer than the other. Overall growth also may slow.

Some children with juvenile arthritis have eye problems, called iridocyclitis. This is treatable by an ophthalmologist (eye doctor). The presence of eye problems helps to confirm the diagnosis. Without treatment, iridocyclitis can result in eye damage that cannot be cured. Most patients do not have any symptoms of iridocyclitis and the only way to diagnose this early is by slit lamp examination.

Signs of Juvenile Arthritis

The most common type of juvenile arthritis is juvenile idiopathic arthritis, formerly known as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.

Children as young as two may be affected. Other rheumatic diseases affecting children include juvenile dermatomyositis, juvenile psoriatic arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and systemic arthritis, or Still’s disease. In these diseases, a child’s immune system malfunctions for some reason, attacking her body instead, especially her joints. Here are the common symptoms of juvenile arthritis, and why they are different from symptoms caused by other illnesses or injuries.

Pain: Kids complain of pain in joints or muscles at times, particularly after a long day of strenuous activity. But a child with juvenile arthritis may complain of pain right after she wakes up in the morning or after a nap. Her knees, hands, feet, neck, or jaw joints may be painful. Her pain may lessen as she starts moving for the day. Over-the-counter pain relief drugs like acetaminophen or ibuprofen may not help. Unlike pain caused by an injury or other illnesses, JA-related pain may develop slowly, and in joints on both sides of the body (both knees or both feet), rather than one single joint.

Stiffness: A child with JA may have stiff joints, particularly in the morning. He may hold his arm or leg in the same position, or limp. A very young child may struggle to perform normal movements or activities he recently learned, like holding a spoon. JA-related stiffness may be worse right after he wakes up and improve as he starts moving.

Swelling: Swelling or redness on the skin around painful joints is a sign of inflammation. A child may complain that a joint feels hot, or it may even feel warm to the touch. A child’s swelling may persist for several days, or come and go, and may affect her knees, hands and feet. Unlike swelling that happens right after a fall or injury during play, this symptom is a strong sign that she has juvenile arthritis.

Fevers: While children commonly have fevers caused by ordinary infectious diseases like the flu, a child with JA may have frequent fevers accompanied by malaise or fatigue. These fevers don’t seem to happen along with the symptoms of respiratory or stomach infections. Fevers may come on suddenly, even at the same time of day, and then disappear after a short time.

Rashes: Many forms of juvenile arthritis cause rashes on the skin. Many kids develop rashes and causes can range from poison ivy to eczema or even an allergic reaction to a drug. But faint, pink rashes that develop over knuckles, across the cheeks and bridge of the nose, or on the trunk, arms and legs, may signal a serious rheumatic disease. These rashes may not be itchy or oozing, and they may persist for days or weeks.

Weight loss: Healthy, active children may be finicky about eating, refusing to eat because they say they’re not hungry or because they don’t like the food offered. Other children may overeat and gain weight. But if a child seems fatigued, lacks an appetite and is losing rather than gaining weight, it’s a sign that her problem could be juvenile arthritis.

Eye problems: Eye infections like conjunctivitis (pinkeye) are relatively common in children, as they easily pass bacterial infections to each other during play or at school. But persistent eye redness, pain or blurred vision may be a sign of something more serious. Some forms of juvenile arthritis cause serious eye-related complications such as iritis, or inflammation of the iris and uveitis, inflammation of the eye’s middle layer.

While many early symptoms of juvenile arthritis could be easily mistaken for other childhood diseases or injuries that aren’t serious or long-lasting, it’s important for parents to get a proper examination and diagnosis from their pediatrician. Juvenile arthritis includes many different diseases, but one common thread between them is that it can have serious, even life-threatening impacts on a young child. Diagnosis by a physician can determine the cause of the symptoms, rule out injuries or other diseases, and suggest treatments that will ease symptoms and allow your child to return to school and resume playing with friends and enjoying childhood.

Juvenile Arthritis Symptoms

Each of the different types of JA has its own set of signs and symptoms. You can read more specifics about the diseases by following the links above, and by visiting the Arthritis Foundation’s website dedicated to pediatric rheumatic diseases.

Complications

Several serious complications can result from juvenile idiopathic arthritis. But keeping a careful watch on your child’s condition and seeking appropriate medical attention can greatly reduce the risk of these complications:

Eye problems. Some forms can cause eye inflammation (uveitis). If this condition is left untreated, it may result in cataracts, glaucoma, and even blindness.

Eye inflammation frequently occurs without symptoms, so it’s important for children with this condition to be examined regularly by an ophthalmologist.

Growth problems. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis can interfere with your child’s growth and bone development. Some medications used for treatment, mainly corticosteroids, also can inhibit growth.

Juvenile Arthritis Diagnosis

The most important step in properly treating juvenile arthritis is getting an accurate diagnosis. The diagnostic process can be long and detailed. There is no single blood test that confirms any type of JA. In children, the key to diagnosis is a careful physical exam, along with a thorough medical history. Any specific tests a doctor may perform will depend upon the type of JA suspected.

PHYSIOTHERAPY FOR JUVENILE ARTHRITIS

Juvenile arthritis (JA), or arthritis in children ages 16 and younger, can limit a patient’s physical activity because of the joint and muscle pain, stiffness, and discomfort associated with the disease, and these children are known to be less physically active than their peers.

However, exercise has been linked to a positive outcome in children with JA. Studies of physical activity and JA find these young patients report fewer symptoms, increased confidence, and improved physical fitness.

What is the purpose of physiotherapy for juvenile arthritis?

On average, patients lose muscle mass and flexibility during a flare, or period in which symptoms significantly worsen. Typically they are not able to regain these abilities in between flare-ups, so their physical fitness slowly declines over time.

Physiotherapy aims to improve joint flexibility, muscle strength, and the overall fitness level of children with JA. Medications may help to relieve some of the pain and inflammation associated with the disease, so therapy plans that include both pharmaceutical treatments and physiotherapy are often recommended both to relieve symptoms and to limit the detrimental effects of the disease on a child’s growth and physical development.

How does Physiotherapy for juvenile arthritis work?

A physiotherapist, or a physical therapist, will assess a patient’s joints, muscles, and range of motion to develop an individualized treatment plan. Usually, this plan includes exercises that should be done regularly at home, in addition to those completed at the clinic.

Stretching is a key part of therapy. With the help of a physiotherapist, patients will stretch muscles, one at a time. This is beneficial even if the patient is experiencing a flare. Exercises to improve muscle strength and stamina will be included. Typically, these are highly repetition-low weight resistance exercises that target specific muscles or muscle groups.

Physiotherapists may also recommend assistive devices for children with JA, such as splints, which can help to keep joints properly aligned and passively stretch them. They may recommend using ice or heat packs to reduce swelling.

Although not part of a physiotherapy treatment plan, JA patients are usually advised to in sports and fitness activities, such as swimming and cycling, as often as possible. A hydrotherapist can help patients learn of low-impact exercises that can be done in a pool to improve range of movement and stamina.

The juvenile Arthritis article is strictly information about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health providers with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

Related Other Rheumatoid Disease :

2 Comments