Developmental Delay

Developmental Delay is when your child does not reach their developmental milestones at the expected times. It is an ongoing major or minor delay in the process of development. If your child is temporarily lagging behind, that is not called developmental delay.

Children with developmental delay take longer to develop new skills than most other children.

See your GP or child and family health nurse if you think your child might have developmental delay.

Health and education professionals can support children with development delay.

When young children are slower to develop physical, emotional, social and communication skills than expected, it’s called developmental delay.

Developmental delay can show up in the way children move, communicate, think and learn, or behave with others. When more than one of these areas is affected, it might be called global developmental delay.

Developmental delay might be short term, or it might be the first sign of a long-term problem.

Long-term developmental delays are also called developmental disabilities. Examples include learning disabilities, cerebral palsy, intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder.

Every child develops differently, and there’s a big range of ‘normal’ in children’s development.

But as a general guide, you might be concerned about developmental delay if you notice that, over several months, your child isn’t developing motor, social or language skills at the same rate as other children the same age.

As a parent, you know your child better than anyone else.

If you’re concerned about your child’s development, trust your instincts and talk to your GP, child and family health nurse or paediatrician.

These health professionals can diagnose developmental delay after assessing your child. Or they can refer you to other professionals who can help.

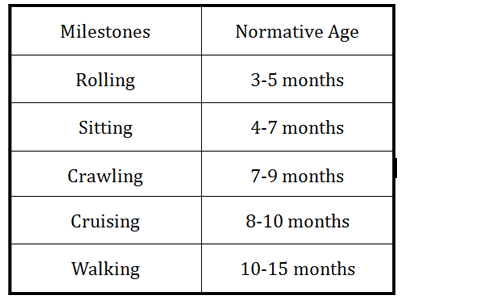

Developmental milestones are skills or tasks that children can typically do at certain ages. Crawling, walking, and talking are three examples. Doctors use developmental milestones to check on a child’s development and make sure there are no issues that need to be addressed. All children are unique and develop at different rates, but most children will hit their milestones within a certain age range. If a child doesn’t reach his or her milestones on time, it could be a sign of developmental delay.

Developmental delay may be caused by a variety of factors, including heredity, problems with pregnancy, and premature birth. The cause is not always known. If you suspect your child has developmental delay, speak with your pediatrician. Developmental delay sometimes indicates an underlying condition that only doctors can diagnosis. Early intervention will help your child’s progress and development into adulthood.

Table of Contents

Fine and gross motor skill delay

Fine motor skills include small movements like holding a toy or using a crayon. Gross motor skills require larger movements, like jumping, climbing stairs, or throwing a ball.

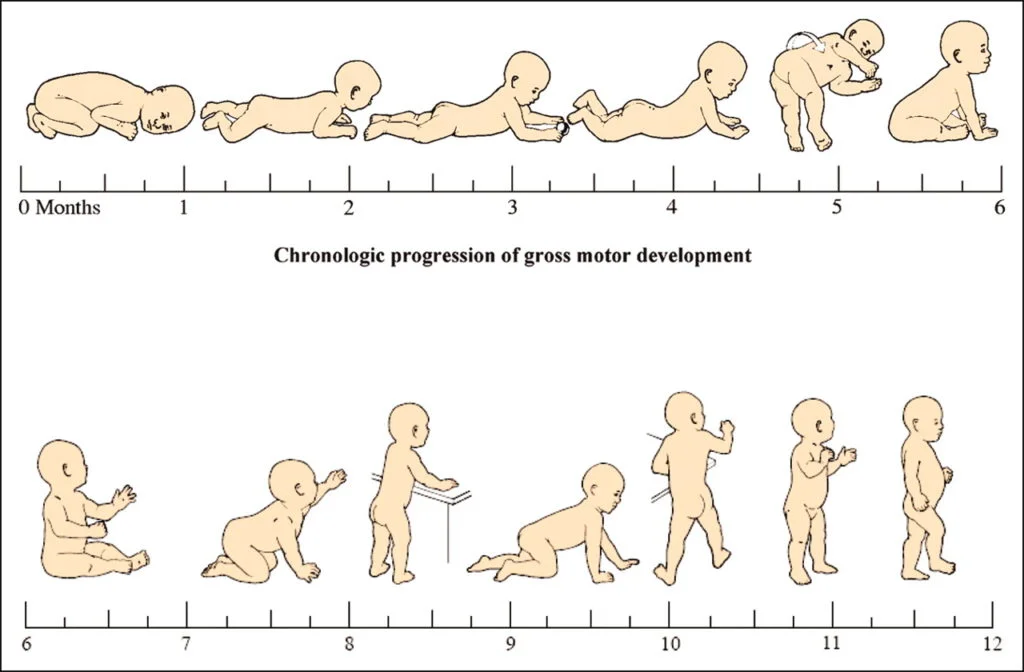

Children progress at different rates, but most children can lift their head by 3 months old, sit up by 6 months, and walk well before their 2nd birthday. By age 5, most children can throw a ball overhand and ride a tricycle.

Exhibiting some of the following symptoms can mean that your child has delays in developing some fine or gross motor functions:

floppy or loose trunk and limbs

stiff arms and legs

limited movement in arms and legs

can’t sit without support by 9 months old

involuntary reflexes have dominance over voluntary movements

can’t bear weight on legs and stand up by about 1 year old

Falling outside the normal range is not always cause for concern, but if your child is unable to perform tasks within the expected time frame, speak to your doctor.

Speech and language delay

According to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), the most active time for learning speech and language is the first three years of life, as the brain develops and matures.

The language learning process begins when an infant communicates hunger by crying. By 6 months old, most infants can recognize the sounds of basic language. At 12 to 15 months old, infants should be able to say a few simple words, even if they aren’t clear. Most toddlers can understand a few words by the time they are 18 months old. When they reach the age of 3, most children can speak in brief sentences.

Speech and language delay are not the same. Speaking requires the muscle coordination of the vocal tract, tongue, lips, and jaw to make sounds. Speech delay is when a child stutters or has difficulty producing sounds the correct way. A disorder that makes it hard to put syllables together to form words is called apraxia of speech.

A language disorder occurs when children have difficulty understanding what other people say, and can’t express their own thoughts. Language includes speaking, gesturing, signing, and writing.

Poor hearing can cause speech and language delay, so your doctor will usually include a hearing test during diagnosis. Children with speech and language delay are often referred to a speech-language pathologist. Early intervention can be a big help.

Autism spectrum disorders

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that can impair your child’s ability to communicate and interact with others. Classic autism usually includes language delay and intellectual disabilities. Symptoms are sometimes obvious early on, but may not be noticed until a child reaches 2 or 3 years of age.

Signs and symptoms of autism vary, but usually include delayed speech and language skills and difficulty communicating and interacting with others. Each child will have a unique pattern of behavior with differing levels of severity. Some symptoms include:

failure to respond to their name

resistance to cuddling or playing with others

lack of facial expression

doesn’t speak or has difficulty speaking, carrying on a conversation, or remembering words and sentences

performs repetitive movements

develops specific routines

coordination problems

There is currently no cure for autism but early intervention and education can help your child progress more fully.

Causes and risk factors of developmental delay

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about 15 percent of children between the ages of 3 and 17 have one or more developmental disability. Most developmental disabilities occur before a child is born but some can occur after birth due to infection, injury, or other factors.

Causes of developmental delay can be difficult to pinpoint and a variety of things can contribute to it. Some conditions are genetic in origin, such as Down syndrome. Infection or other problems during pregnancy and childbirth, as well as premature birth, can also cause developmental delay.

Developmental delay can also be a symptom of other underlying medical conditions, including:

autism spectrum disorders (ASDs)

cerebral palsy

fetal alcohol spectrum disorders

Landau-Kleffner syndrome

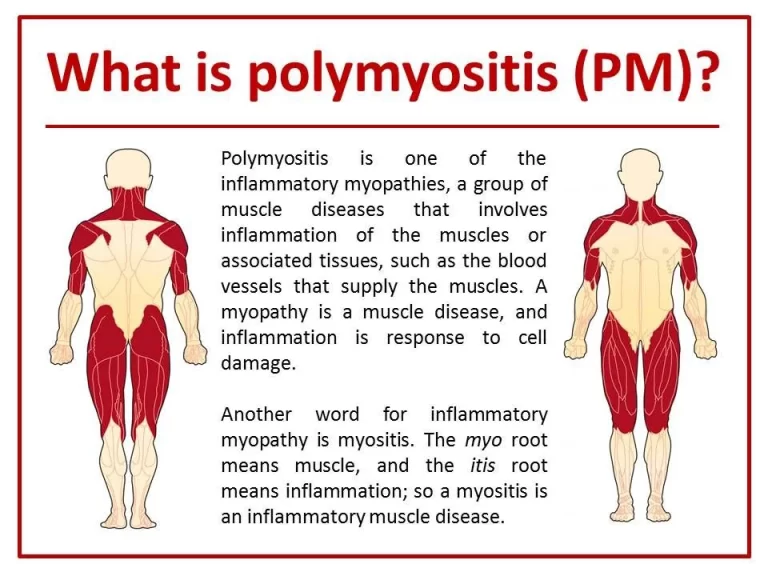

myopathies, including muscular dystrophies

genetic disorders, such as Down syndrome and fragile X syndrome

Signs and Symptoms of Developmental Delay

Parents are often the first to notice a child isn’t hitting their milestones in 1 of the 5 areas of development mentioned above. However, lagging behind on a milestone attainment does not necessarily mean a child has developmental delay. Children need to demonstrate a significant delay in 1 or more areas of development.

For example, in infancy a child is first suspected to have developmental delay if common motor milestones are not being met, such as:

Holding the head up by 4 months

Sitting by about 6 months

Walking by about 12 months

Children might be suspected of having a motor developmental delay if they are not exploring movement in a variety of ways. Sometimes children who have a motor developmental delay may also have an additional diagnosis, such as hypotonia (low muscle tone) that contributes to their difficulty with movement.

Motor development in children can often be the first area of delay that is noticed by caregivers. However, in infants and young children, all areas of development are closely connected; a delay in one area can impact progress in another. For example, learning about objects or babbling and talking can be affected if a child does not learn to sit or change positions. Sensory problems, such as hypersensitivity to touch or an inability to plan and problem-solve how to move, may also add to movement difficulties.

Children who have some or all of these problems that inhibit their movement development also may develop a fear of trying new motor skills, which can then lead to social or emotional problems.

Types of Developmental Delays in Children

Pediatric specialists at Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital at NYU Langone identify several types of developmental delays in children. These delays can affect a child’s physical, cognitive, communication, social, emotional, or behavioral skills.

Often, developmental delays affect more than one area of a child’s development. When a child has delays in many or all of these areas, it is called global developmental delay.

Some developmental delays have an identifiable cause. However, for many children, the cause of the delay, or multiple delays, is not clear.

Cognitive Delays

Cognitive delays may affect a child’s intellectual functioning, interfering with awareness and causing learning difficulties that often become apparent after a child begins school. Children with cognitive delays may also have difficulty communicating and playing with others.

This type of delay may occur in children who have experienced a brain injury due to an infection, such as meningitis, which can cause swelling in the brain known as encephalitis. Shaken baby syndrome, seizure disorders, and chromosomal disorders that affect intellectual development, such as Down syndrome, may also increase the risk of a cognitive delay. In most cases, however, it is not possible to identify a clear reason for this type of delay.

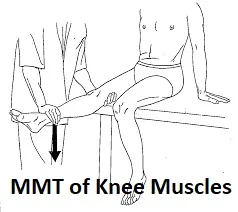

Motor Delays

Delays in motor skills interfere with a child’s ability to coordinate large muscle groups, such as those in the arms and legs, and smaller muscles, such as those in the hands. Infants with gross motor delays may have difficulty rolling over or crawling; older children with this type of delay may seem clumsy or have trouble walking up and down stairs. Those with fine motor delays may have difficulty holding onto small objects, such as toys, or doing tasks such as tying shoes or brushing teeth.

Some motor delays result from genetic conditions, such as achondroplasia, which causes shortening of the limbs, and conditions that affect the muscles, such as cerebral palsy or muscular dystrophy. They may also be caused by structural problems, such as a discrepancy in limb length.

Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Delays

Children with developmental delays, including those with related neurobehavioral disorders such as autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, often also have social, emotional, or behavioral delays. Due to differences in brain development, they may process information or react to their environment differently than children of the same age. These delays can have an impact on a child’s ability to learn, communicate, and interact with others.

It is common for children with developmental delays to have difficulty with social and emotional skills. For example, they may have trouble understanding social cues, initiating communication with others, or carrying on two-way conversations. They may also have difficulty dealing with frustration or coping with change. When the environment becomes too socially or emotionally demanding, children with developmental delays may have prolonged tantrums and take longer than other children to calm down. This behavior can be a signal that the child needs more support by modifying his or her environment or learning skills to cope with social and emotional challenges.

Speech Delays

Some speech delays are receptive language disorders, in which a child has difficulty understanding words or concepts. Children with this type of speech delay may have trouble identifying colors, body parts, or shapes. Others are expressive language disorders, in which a child has a reduced vocabulary of words and complex sentences for his or her age. A child with this type of speech delay may be slow to babble, talk, and create sentences. Often, a child with a speech delay has a combination of receptive and expressive delays.

Children with an oral motor problem—such as weakness in the muscles of the mouth or difficulty moving the tongue or jaw—that interferes with speech production have what is known as a speech production disorder.

Children may have speech delays due to physiological causes, such as brain damage, genetic syndromes, or hearing loss. Other speech delays are caused by environmental factors, such as a lack of stimulation. In many instances, however, the cause of a child’s speech delay is unknown.

Diagnosis of Developmental Delay

Parents should first talk to their pediatrician about any concerns they have regarding their child’s development. A physician can identify medical problems that may be having an impact on overall development, such as chronic ear infections that reduce hearing and affect the child’s speech development or balance.

Developmental delay is diagnosed by using tests designed to score a child’s movement, communication, play, and other behaviors compared with those of other children of the same age. These tests are standardized—scored on hundreds of children—in order to determine a normal range of scores for each age. If children score far below the average score for their age, they are at risk for developmental delay.

A pediatrician usually will perform a screening test during infancy to determine if a child is progressing at an age-appropriate rate, often at the request of a parent who suspects the child is not performing the same skills as other children of the same age. A screening test helps to identify which children would benefit from a more in-depth evaluation. A physical therapist, who has knowledge of movement development, coordination, and medical conditions, will perform an in-depth examination to determine if a child’s motor skills are delayed and, if so, by how much they are delayed.

Your physiotherapist will first evaluate your child, conducting an appropriate and detailed test to determine the child’s specific strengths and weaknesses. Your physical therapist will discuss your observations and concerns with you. If the child is diagnosed as having developmental delay, your physical therapist will problem-solve with you about your family’s routines and environment to find ways to enhance and build your child’s developmental skills.

In addition to evaluating your child and the environment in which the child moves, the physical therapist can give detailed guidance on building motor skills 1 step at a time to reach established goals. The therapist may guide the child’s movements or provide cues to help the child learn a new way to move. For example, if a child is having a hard time learning to pull herself up to a standing position, the physical therapist might show her how to lean forward and push off her feet. If a child cannot balance while standing, the physical therapist may experiment with various means of support, so he can safely learn new ways to stand.

The physiotherapist will also teach the family what they can do to help the child practice skills during everyday activities. The most important influence on the child is the family, because they can provide the opportunities needed to achieve each new skill.

Your physiotherapist will explain how much practice is needed to help achieve a particular milestone. A child learning how to walk, for example, covers a lot of ground during the day; your physical therapist can provide specific advice on the amount and type of activities appropriate for your child at each stage of development.

Physiotherapy Treatment of Developmental Delay

Physiotherapists are mainly concerned with the development of body postures and large movements (which require gross motor skills). Physiotherapy treatment aims to promote a child’s independence and ability to reach physical milestones. Physiotherapists often use fun games and activities to help promote learning and normal development. Treatment is outlined specific to a child’s needs, age and abilities. They collaborate with parents, teachers and caretakers to help them understand the child’s needs and how they can help promote future independence.

There are various benefits that your child can take away such as:

Improved independence in activities of daily living

Achievement of physical milestones such as sitting, standing and crawling

Improved confidence

Improved posture, muscle strength, balance and coordination

Exercises to increase muscle strength and control so that your child is able to shift their body weight and balance better

Muscle stretching to lengthen muscles, increasing range of movement and preventing muscles and joints from becoming stiff

Activities to improve head and trunk control. For example, supporting your child in sitting to develop weight shifting, rotation, coordination and balance. Mirror imaging is often used to increase their awareness of where their limbs are in space (prioprioception)

Exercises to increase mobility and their success of learning to walk based around everyday activities Physiotherapy may involve exercise for the hand to improve writing and grasping objects

Advice about supportive devices such as using a wheelchair, orthotic devices or other adaptive equipment if necessary

Hydrotherapy treatment helps relax stiff muscles and joints and maximises mobility in water

When a child is diagnosed with developmental delay disorder the future can look daunting for parents. Physiotherapists can provide assessment and treatment for your child to give them the best chance possible to achieve their physical milestones.

The Rehabilitation Services Department at CHOC Children’s provides physical therapy for children of all ages, from birth through age 21. All of our therapies are designed to meet each patient’s specific needs with the goal of teaching the child how to successfully navigate his or her environment. We teach each patient’s family how to help their child achieve their developmental milestones and work to develop exercises, therapy and experiences that benefit the child and his or her family. We challenge the child to explore his or her environment while still maintaining a safe experience. As part of therapy, therapists work to stimulate:

The neural centers: groups of nerves that work together to produce movement.

The vestibular system: the sensory system that controls balance and coordination with movement.

The proprioceptive centers: bundles of tissue that help us know where our body is in space.

The sensory organs: ears, eyes, mouth, skin and nose.

Muscles.

Congenital muscular torticollis and plagiocephaly.

Developmental delay / hypotonia.

Idiopathic toe walking.

Balance and coordination disorders.

2 Comments