Shoulder Examination

Table of Contents

What is a Shoulder Examination?

The shoulder examination is a critical aspect of assessing shoulder pain or dysfunction, helping to identify the underlying causes and guide appropriate treatment. The shoulder is a complex joint with a wide range of motion, relying on the coordinated function of muscles, tendons, and ligaments.

A thorough shoulder examination typically includes an evaluation of the patient’s history, observation of posture and alignment, palpation to identify areas of tenderness or swelling, and a series of specific tests to examine muscle strength(MMT), range of motion(ROM), and stability of the joint. Accurate diagnosis through a detailed shoulder examination is essential for effective management and rehabilitation of shoulder conditions.

The shoulder complex is challenging to evaluate due to its numerous components (the majority of which are concentrated in a limited region), numerous motions, and several lesions that can develop inside or outside the joints.

It is ensured that significant problems are noticed and that crucial features of the condition are identified when doing the shoulder history and examination in a systematic and planned manner. Decisions on the necessity of more testing, investigations, and continuing care can be made with the use of the information acquired throughout this procedure.

It should be noted that evaluation procedures based on diagnostic imaging and clinical testing have been questioned over time, with clinical testing being unable to identify the structures causing pain accurately. Much discussion surrounds the proper interpretation of diagnostic imaging.

Relevant Anatomy:

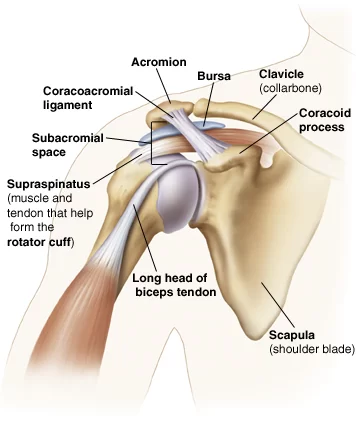

The glenohumeral joint is not the only source of the arm’s range of motion (ROM) for the trunk. Additionally, there is movement in the upper costosternal costovertebral, acromioclavicular, and sternoclavicular joints. The scapula’s freedom of motion to the dorsal thoracic wall is another need for proper mobility.

The multiaxial, ball-and-socket synovial glenohumeral joint has a somewhat shallow socket called the glenoid cavity. The muscles and ligaments are the primary sources of reliance for the joint in terms of support, stability, and integrity. About 50% of the glenoid cavity of the scapula is surrounded and deepened by the ring of fibrocartilage labrum, also known as the glenoid labrum.

The majority of stability is provided by the periarticular muscles, which connect the scapula to the caput humeri.The m. supraspinatus, m. infraspinatus, and m. subscapularis are parts of the rotator cuff. The dorsal side bony ridge known as the spina scapulae is where the m. trapezius and m. deltoideus enter. The spina scapulae widen on the lateral side to produce the acromion.

The subacromial space is the area that exists between the acromion and the humeral head. This region contains the bursa subacromialis, also referred to as the bursa subdeltoid, and the rotator cuff tendons. The tendon of the caput longum m. biceps brachii goes through the sulcus intertubercular, which divides the tuberculum major and tuberculum minus. At the upper ridge of the glenoid cavity, also known as the labrum glenoidale, this tendon inserts itself and continues into the joint.

Medical History

When a patient recalls their previous medical experiences, it is referred to as “anamnesis.” An important component of the evaluation of patients with musculoskeletal dysfunction is the anamnesis. Different anamnestic elements are collected including

Characteristics of symptoms

Mechanisms of pain

Patients’ preferences, expectations, and psychosocial issues (yellow flags)

Each of these components has a weight, and the clinical reasoning process uses them to direct the physical examination that follows.

Patient History

It is important to thoroughly analyze the patient’s past medical history as it can help rule out any abnormalities and direct the examination of the shoulder.

The presenting condition’s history, the length of time the complaints have lasted, how it developed, and whether there was ever a traumatizing event.

Distribution and intensity of pain: sleep disturbance, patient’s ability to lie on the afflicted side, and the extent of difficulty with day-to-day tasks at work and home.

Self-control as well as other therapy Previous experiences of the patient with shoulder problems, including the direction, result, and therapy

Relation between the complaints and work situation

Relation between the complaints and sports activities

Chief Complaints

- The pain’s location—radiation in the arm

- Activities that are aggravating, such as challenges with overhead tasks, lifting goods, everyday living tasks, sports, or leisure activities

- discomfort when moving the upper arm in one or more directions

- A sense of unpredictability

- Additional neck complaints

Mechanism of Injury

It is important to inquire about the process underlying each given injury, with special attention to three aspects related to the moment of damage: anatomical location, limb posture, and subjective sensations. Make sure you understand the patient when they describe the anatomical place. Describing the arm’s position at the time of the accident is also beneficial.

The danger of shoulder dislocation or subluxation, for instance, increases when one falls on an abducted and externally rotated arm. Lastly, it may be helpful to investigate the patient’s subjective sensations at the scene of the accident. A bone or ligament breaking, for instance, may be indicated by a snapping or cracking sound, and a joint dislocation or subluxation may be indicated by feeling something “pop out.”

Physical Examination

Make the Cervical Spine Clear

- Pain in the shoulder and scapular area may be referred from the cervical spine. Appropriate screening of the cervical spine is essential as the patient’s clinical presentation may be influenced by it.

Observation

- At this point in the shoulder examination, the key concept is symmetry. Each shoulder should be comparatively identical in terms of form, location, and function. Shoulder dominance can lead to certain changes; the dominant shoulder may sit lower and have a somewhat bigger appearance because of its larger muscular mass. Check the scapula’s position, winging, and any odd stances connected to injuries or swellings.

Palpation:

The physical therapist may get important information by palpating the shoulder area. The presence of edema, texture, and warmth should all be noted by the physical therapist. Physical therapists may also notice asymmetry, variations in sensation, and the transmission of pain. Important structures to feel include:

- Acromioclavicular Joint

- Sternoclavicular Joint

- Rotator Cuff Muscle Insertions

- Long Head of the Biceps Tendon

- Sensitivity and changed perception (personal) regional or recommended

- Objective: The skin’s temperature and texture; a tight, hot surface could be a sign of an infection, an inflammation, a tumor, or synovitis.

- Swelling could be a sign of a tumor, nodule, effusion, or alterations in the bone.

Movement-related crepitus is a symptom of tendinopathy, osteoarthritis, and fractures.

Neurologic Assessment

Patients whose major complaint is shoulder discomfort may benefit from a thorough neurological assessment. In the situation that neurological symptoms like tingling and numbness are present, this evaluation can be required.

Myotomes

- C4 – Shoulder Elevation/Shrug

- C5 – Shoulder Abduction

- C6 – Elbow Flexion, Wrist Extension

- C7 – Elbow Extension, Wrist Flexion

- C8 – Thumb Abduction/Extension

- T1 – Finger Abduction

Dermatomes

- C4 – Top of Shoulders

- C5 – Lateral Deltoid

- C6 – Tip of Thumb

- C7 – Distal Middle Finger

- C8 – Distal 5th Finger

- T1 – Medial Forearm

Pathological Reflexes

Hoffmann’s Reflex

Inverted Supinator Reflex

Deep Tendon Reflexes

- Biceps Brachii – C5 Nerve Root

- Brachioradialis – C6 Nerve Root

- Triceps – C7 Nerve Root

Testing of Movement

All of the functional planes of the shoulder are actively used by the patient. This encompasses internal and exterior rotation, flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction. Determine the damaged shoulder’s range of motion or measure it with a goniometer, then compare it to the usual predicted range and the unaffected shoulder.

Active Range of Motion (ROM)

Active movements of the shoulder complex ROM

- Elevation through abduction 170°-180°

- Elevation through forward flexion 160°-180°

- elevation between the scapula’s plane 170°-180°

- Lateral (external) rotation 80°-90°

- Medial (internal) rotation 60°-100°

- Extension 50°-60°

- Adduction 50°-75°

- Horizontal adduction/abduction

- (cross-flexion/ cross-extension) 130°

- Circumduction 200°

- Scapular protraction

- Scapular retraction

- Combined movements (if necessary)

- Repetitive movements (if necessary)

- Sustained positions (if necessary)

Dysfunction – affecting movements:

These movements are limited, as this can help isolate the problem.

The following conditions may affect your shoulder movements:

- Pain: tendinopathy, impingement, sprain/strain, labral pathology

- Frozen shoulder and labral illness (see MRI image on the right) are the mechanical blockages.

- Night pain (sleeping on the affected shoulder): pathology of the rotator cuff, anterior shoulder instability, injury to the ACL, and neoplasm (especially persistent)

- A Sensation of ‘clicking or clunking’: labral pathology, unstable shoulder (either anterior or multidirectional instability)

- A Sensation of stiffness or instability: frozen shoulder, anterior or multidirectional instability

Passive ROM:

It may incorporate every action listed in the section with active ROM. To put more strain on the joint, the therapist could decide to apply excessive pressure.

Muscle Length Assessment:

Among these muscles could include, but are not restricted to:

- Latissimus Dorsi

- Pectoralis Minor/Major

- Levator Scapulae

- Upper Trapezius

- Scalenes (anterior/middle/posterior)

Muscle Strength (Manual Muscle Testing):

In order to assess the shoulder muscles’ resistance, the following actions are typically carried out:

- Shoulder Flexion

- Shoulder Extension

- Shoulder Abduction

- Horizontal Abduction

- Horizontal Adduction

- Internal Rotation

- External Rotation

Tests that are resistant to activating the scapular stabilization muscles include:

- Upper trapezius

- Middle trapezius

- Lower trapezius

- Serratus Anterior

- Rhomboids

- Levator Scapulae

Joint Mobility Assessment:

A joint’s assessment of mobility may reveal hypomobility there and/or exacerbate symptoms.

Glenohumeral:

- Anterior

- Posterior

- Inferior

- Distraction

Acromioclavicular:

- Anterior

- Posterior

Sternoclavicular:

- Anterior

- Posterior

- Superior

- Inferior

Scapulothoracic:

- Elevation

- Depression

- Upward/downward rotation

- Protraction/Retraction

Special Tests:

There are various specialized diagnostics available for certain shoulder diseases. The links to the individual pages describing the unique testing for each pathology are provided below:

- Subacromial Related Shoulder Pain

- Biceps Tendinopathy

- Labral Tears

- Laxity/Instability

Rotator cuff examination test:

Supraspinatus Test:

- The rotator cuff tendon that sustains injuries most commonly is the supraspinatus tendon. To assess the strength of the supraspinatus, we can have the patient abduct both arms to a 90° angle and then bring them forward by 30°. We will instruct the patient to thrust both arms upward against our resistance from this posture. Any discomfort or weakness, particularly if one side is affected, will indicate a supraspinatus tendon injury.

- The empty can test can also be requested of the patient, who starts in this position and moves both thumbs downward. We can push downward against the patient’s resistance to check for discomfort and weakness.

Teres Minor and Infraspinatus test:

- External rotation of the shoulder must be done resistively to evaluate the condition of the teres minor and infraspinatus tendons. The patient will be taught to do this by flexing their forearms with their palms supinated at a 90-degree angle. We will tell the patient to move their forearms laterally against our resistance to externally rotate their shoulders from this posture. A rupture to one of these tendons will be confirmed by any pain and/or weakness.

A subscapularis test:

- Request that the patient place their hand at the level of their lumbar region on their back in order to feel for any signs of a ruptured subscapularis tendon. After that, gradually remove the hand from the back until the shoulder has completed its internal rotation. Now ask the patient to actively take their hand off their back. An indication of subscapularis tendon injury, the patient’s incapacity to do so is called a “positive internal rotation lag sign.”

Gerber Lift-Off Examination test:

- Ask the patient to internally rotate their shoulder by putting the hand behind their back in the lumbar area and facing the lumbar spine with the dorsum of the palm. After that, suggest that the patient remove their hand from their back, against your resistance. If the test results in pain or weakness, it is considered positive for a subscapularis tendon injury.

Serratus Anterior test:

- In recognition of its role in supporting the scapula, this muscle—while not officially classified as a part of the rotator cuff—allows us to evaluate its strength following the rotator cuff examination. and, by extension, the shoulder joint.

- One possibility is doing a standing push-up test on the patient to rule out a functional impairment of the serratus anterior. A winging of the scapula signifies a weakening in that particular muscle on that side.

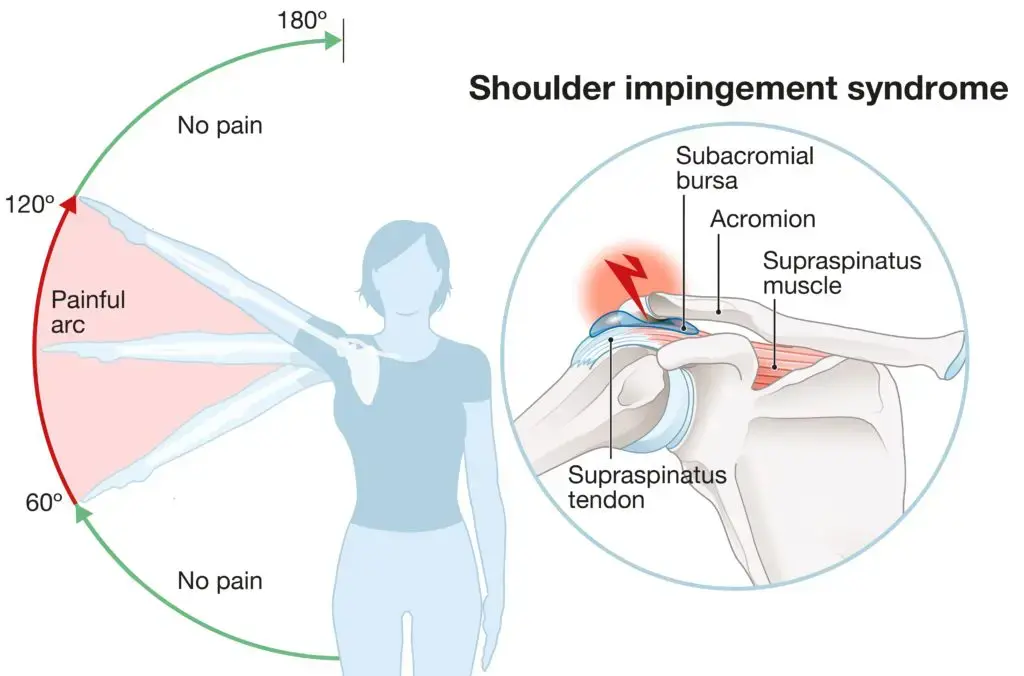

Shoulder Impingement test:

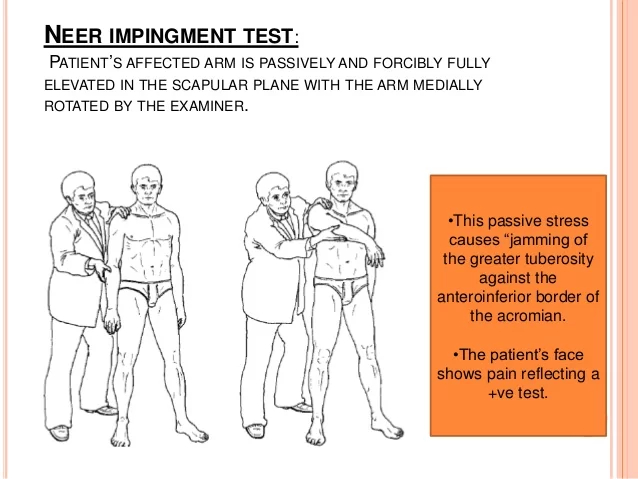

Neer’s Examination test:

- The Neer’s test requires the patient to fully extend their forearm before passively flexing it till it is over their head. This motion narrows the subacromial space, increasing any pain if shoulder impingement is present.

The Hawkins-Kennedy test:

- The elbow and shoulder must be flexed to a 90° angle to finish this test. To encourage the patient’s upper extremities to relax as much as possible, the examiner must support the patient’s arm at elbow level. Abducting the arm cross-body and internally rotating the shoulder are the following steps the examiner must perform. If pain occurs during the test, it is positive.

Empty can test:

- The supraspinatus tendon’s integrity can be evaluated clinically with the empty can test. The subject is tested with the scapular plane elevated 90 degrees and with complete internal rotation (empty can). The person being tested responds when the examiner attempts to apply downward pressure on their wrist or elbow.

- The test is considered successful if there is any weakness or pain during resistance. A positive test result could suggest disease (such as suprascapular nerve entrapment) or injuries to the supraspinatus tendon or muscles.

Biceps Tendinopathy examination test:

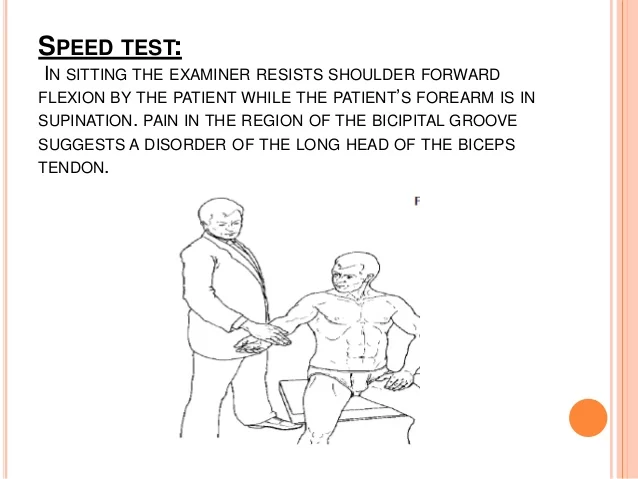

Speed’s test:

- During this examination, the patient is required to fully supinate their forearm and then extend their elbow. After that, the patient is instructed to bend their shoulder forward against the examiner’s opposition. The examiner should palpate the anterior joint line and feel for any pain at the same time. Any discomfort that the exercise causes biceps tendinopathy symptoms.

Yergason’s Test:

- The patient is first told to bend their elbow to a 90° angle and extend their forearm. The patient is then told to supine their forearm against the examiner’s resistance, which might include the examiner grasping their hand. Examiners should simultaneously feel for any pain or popping feeling at the tendon’s origin in the biceps. A pain response indicates that the test was successful.

Adhesive Capsulitis Examination Test:

- Adhesive capsulitis is a condition in which the capsule around the shoulder joint becomes inflamed and rigid, making movement extremely painful and difficult. Pain with shoulder movement in all directions characterizes the disease’s early stages. Although the discomfort tends to decrease in the latter stages, the range of motion is still significantly restricted. Recall that both passive and active ranges of motion are impacted. The range of motion is initially impacted by external rotation. In addition, asymmetry in scapular movement is typically seen.

- In conclusion, these individuals may have trapezius muscular pain and spasms. Therefore, palpate the upper half of the trapezius to cause discomfort and reduce muscle tension.

Acromioclavicular Joint Disease examination test:

Scarf Test:

- The examiner does the scarf test by placing the hand from the affected side on the other shoulder. It then pushes at the elbow to force the arm’s cross-body adduction while at the same time the therapist checks the AC joint. Any discomfort or crepitus may indicate a sign of AC joint damage.

Painful Arc Test:

- The patient is directed to 180° abduction of the affected shoulder. A positive test result indicates an AC joint injury if the patient feels discomfort when their arm is between 180° and 150°.

Shoulder Instability Test:

Sulcus Sign:

- During the test, the examiner pulls on the humerus at the wrist’s level while simultaneously observing the deltoid region’s lateral aspect. It is considered that the test is positive for shoulder instability if a sulcus develops in this area.

Apprehension and Relocation Test:

- For this test, the patient should ideally lie supine on the examination table. The examiner then flexes the elbow to 90 degrees and abducts the shoulder to 90 degrees. Using one hand at the level of the wrist and the other fist behind the shoulder, the examiner now holds downward pressure. If instability is present, this movement should result in pain or discomfort since it dislocates the humerus. If instability is present, we then need to apply downward pressure on the anterior portion of the shoulder to reduce the discomfort as well as their symptoms.

Labral Tears (SLAP lesions) Examination Test:

O’Brien Test:

- The patient is instructed to flex their shoulder to 90 degrees and then adduct it by 10 degrees in O’Brian’s test. We ask the patient to lift their arms from this posture, even when we are resisting. The pain shows a labrum lesion.

Crank’s Test:

- At around 90°, the examiner passively flexes the elbow and abducts the shoulder. The examiner then keeps one hand on the patient’s shoulder and alternatively rotates the patient’s shoulder passively, internally, and externally by providing pressure to the elbow. The test is deemed effective if there are any metallic sounds or shoulder pain.

Outcome Measures:

- Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI)

- Hand, Shoulder, and Arm Disabilities (DASH)

- Constant-Murley Shoulder Outcome Score (CMS)

- University of Pennsylvania Shoulder Score (U-Penn)

- Visual Analogue Scale

- Patient-Specific Functional Scale

Particular Queries:

It is advisable to inquire about any red or yellow flags from patients Presenting with shoulder pain. A thorough medical history is taken as the first step in the screening process, which may include the use of a medical screening questionnaire. Some of the most prevalent red flag problems for patients with shoulder pain are shown in the chart below.

Red Flags:

Red flags are symptoms and indicators that the physiotherapist should be aware of in case of a non-musculoskeletal pathology that could be fatal, such as a fracture, infection, tumor, or inflammatory rheumatic syndrome.

Examples include:

Shoulder weakness and pain on both sides are common symptoms of polymyalgia rheumatica. It is necessary to evaluate these patients for temporal arteritis.

Acute compartment syndrome: May be brought on by an overly tight bandage or cast, or it may develop from substantial limb swelling after an injury. The pain is not equal to the harm. Rarely can limb pulselessness occur, or it appears very slowly.

- Open fractures

- Fractures with nerve or vascular compromise

- Skin, but more particularly joint infections

- Neoplasia

Conditions that can be fatal and cause symptoms similar to shoulder discomfort include transferred ischemic heart pain.

Left Shoulder- -MI 68.7% of patients reported shoulder pain during an acute myocardial infarction

Yellow Flags:

If yellow flags are suspected, the following tools can be used to evaluate them:

The Fear Avoidance Belief Questionnaire (FABQ)

Patients can be effectively screened for depression using depression screening instruments like the Depression Anxiety Screening Scale (DASS) or the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).

By measuring the intensity of the circumstances overall, as well as whether the patient is overstating their pain and symptoms, the Pain Catastrophizing Scale can be used to assess this.

Fractures:

Injury such as falls into an outstretched hand can lead to a fracture. These are known as FOOSH injuries. The following are frequently fractured in the shoulder region:

- Humeral Fractures

- Clavicle Fractures

A direct hit to the shoulder that causes axial compression typically results in clavicle fractures. In the central portion of the collarbone, over 80% of clavicle fractures occur. Surgical intervention is used to treat substantially displaced fractures. One-year functional results and a reduced rate of mal-union are associated with mid-shaft clavicle fractures. For non-displaced clavicular fractures, a trial of conservative care can be appropriate.

Diagnostic Imaging:

Shoulder radiographs can be utilized to detect osteoarthritis of the acromioclavicular and glenohumeral joints, cysts, sclerosis, acromial spurs, or calcific tendonitis. Typical radiographic views could look like this (depending on the healthcare provider):

- Supraspinatus Outlet View

- Scapular Y-View

- Axillary View

- Anterior-Posterior (AP) View

Different shoulder diseases presented in a clinical picture:

Feelings of “looseness or instability” are common in patients with suspected glenohumeral instability or labral disease, especially when abducted and externally rotated.

Individuals who have adhesive capsulitis may first experience painful shoulder pain throughout their entire body along with a progressive loss of range of motion.

Individuals who may have rotator cuff or subacromial dysfunction may experience pain, weakness, or a heavy feeling in their bodies.

Shoulder osteoarthritis: profound joint discomfort, usually confined to the posterior region, that worsens with activity. As the disease progresses, nighttime discomfort becomes more frequent.

FAQs

What are shoulder special tests?

After a thorough examination of the shoulder, which includes the following but is not limited to the patient’s history, the mechanism of the injury, clinical observation, bony and soft tissue palpation, the assessment of active and passive physiological movements, and the assessment of passive Arthokinematic / accessory movements, special testing is typically carried out.

What does a shoulder examination consist of?

Included in this are internal and external rotation, flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction. Determine the range of motion by estimation or measurement using a goniometer, then compare the impacted shoulder to the unaffected shoulder and the typical predicted range.

What is the range of movement for a shoulder exam?

The patient is directed to 180° abduction of the interested shoulder. The test is deemed positive for AC joint injury if the patient reports discomfort when the arm is between 180° and 150°. Pain of arc between 150° and 180°.

What are the red flags for the shoulder exam?

Acute rotator cuff tears are suspected when there is trauma, pain, weakness, or an abrupt loss of arm mobility (with or without trauma). Shoulder lump or swelling: look for signs of cancer. Suspect septic arthritis if the patient has a fever, red skin, a sore joint, or other systemic symptoms.

How many shoulder tests are there?

Acromioclavicular, biceps, labral, and rotator cuff tendon pathology, instability, subacromial impingement, and scapular dyskinesis can all be detected with more than 70 shoulder special tests5 that are now being used in clinical trials.

How to test shoulder stability?

The doctor moves the patient’s forearm gently in the direction of the floor while maintaining shoulder stability with one hand. It’s known as the shoulder’s external rotation. The test is considered successful if the patient feels as though their shoulder may painfully come out of its joint, or if the shoulder does pop out of the joint.

What is a positive test for the shoulder?

An easy method to determine the source of shoulder pain is the O’Brien test, also known as the active compression test. During the test, if you feel pain or click, you might have an irregularity in your acromioclavicular (AC) joint or a torn labrum.

References:

- Shoulder Exam Tutorial. (n.d.). Stanford Medicine 25. https://stanfordmedicine25.stanford.edu/the25/shoulder.html

- Orthopedics, B. S. M. V. (n.d.). Shoulder Exam – Shoulder & Elbow – Orthobullets. https://www.orthobullets.com/shoulder-and-elbow/3037/shoulder-exam

- Funk, L. (2003). SHOULDER EXAMINATION. https://www.shoulderdoc.co.uk/spr/Exam_shoulder.pdf

- Pt, B. S. (2023, November 4). Special Diagnostic Tests for Shoulder Pain. Verywell Health. https://www.verywellhealth.com/special-tests-for-shoulder-pain-2696489

- Kiel, J. (2024, May 13). Special Tests for the Shoulder Exam. Sports Medicine Review. https://www.sportsmedreview.com/blog/special-tests-for-the-shoulder-exam/