Urinary Bladder

Table of Contents

Description

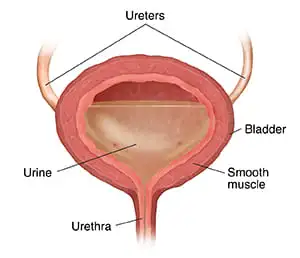

The urinary bladder is a hollow, muscular organ located in the pelvis that serves as a temporary reservoir for urine. Its primary function is to hold urine until it reaches a certain volume, triggering the urge to urinate.

The bladder can expand and contract thanks to its elastic, muscular walls. It plays a crucial role in the urinary system, ensuring that waste products and excess fluids are efficiently removed from the body. Maintaining bladder health is essential for proper urinary function and overall well-being.

It holds almost 1000 ml of urinates, with an average capacity that varies from 400 to 600 ml. Smooth involuntary muscular fibers, or detrusor muscles, form a role in the bladder’s envelope which contracts when a person urinates to empty the bladder.

Anatomical Surface of The Urinary Bladder

When filled, its four surfaces form an oval shape. The abdominal wall parallels the anterosuperior apex. The base, or fundus, is triangular and includes a tip that points backward. It resides posteriorly. The bladder’s body, which fits between the fundus and apex, is its primary component.

The trigon is an angled aim at the site of the bladder that is partially lined by elastin, collagen, and smooth muscle.

Urethral Sphincters

- Internal urethral sphincter

Smooth muscles that are managed by the autonomic nervous system are created. Alpha-adrenergic receptors are located in it, and whenever these receptors are stimulated, the bladder can fill. It is built in females by the neck of the bladder and the proximal urethra (the urethra is 4–5 cm wide in females and 20 cm thick in males).

- External urethral sphincter

It features skeletal muscle filaments, regulates itself involuntarily, and features nicotinic receptors.

Structure of Urinary Bladder

It’s situated in the middle of the pelvis, the urinary bladder is a hollow, muscular organ in humans. The bladder’s gross anatomy consisted of a neck, an apex, a body, and a substantial fundus (base). The median umbilical ligament slides on the back of the anterior abdominal wall to the umbilicus from the apex, which is as well allowed as the vertex, which reaches further toward the top angle of the pubic symphysis.

It builds the middle umbilical fold by bringing the peritoneum from the apex onto the abdominal wall. The area found at the base of the trigone that embraces the internal urethral development which is attached to the urethra is frequently referred to as the bladder’s neck. In men, the prostate gland and the urinary bladder neck are connected.

Three apertures function as the bladder. The two ureters connect the bladder and make use of ureteric orifices, whilst the urethra inserts its accept at the trigone that forms the bladder. Mucosal flaps in front of these ureteric openings serve as valves for inhibiting vesicoureteral reflux, which is the backflow of urine into the ureters. This creates the trigone’s upper boundary.

Function of Urinary Bladder

Blood and lymph supply

Blood arrives at the bladder through the vesical arteries and is discharged into a collection of vesical veins. The upper section of the bladder takes blood supply from the superior vesical artery. The inferior vesical artery, which is a branch of the internal iliac artery, distributes blood to the bladder’s lower section. The uterine and vaginal arteries in females contribute further blood supply.

The bladder’s lateral ligaments connect with a network of small capillaries on its lower lateral surfaces to establish the internal iliac veins, whose venous drainage initiates. The lymph dismis from the bladder initiates an ongoing sequence of networks throughout the mucosal, muscular, and serosal layers. These eventually combine to make three sets of vessels: one set flushes the bladder’s bottom near the trigone, another set discharges the bladder’s top, and a third set drains the bladder’s outer undersurface.

The ureters transmit released urine from the kidneys into the bladder, where it remains lodged until micturition. Urination is a sequential contraction of muscles asking for a spinal reflex and higher brain function inputs. The muscles of the perineum and external urinary sphincter relax, the detrusor muscle contracts, and urine flows into the urethra, through the penis or vulva, before exiting the body through the urinary meatus.

Urges for urination are brought on by stretch receptors, which become active when the bladder collects 300–400 mL of bowel movements. The fibers level and the bladder wall thin as the waste builds up, enabling the bladder to hold more urine without facing a significant rise in internal pressure. The brainstem’s pontine micturition center affects urination.

Nerve supply

Sensory and motor stimuli from the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems contribute to the bladder. The motor supply arises from parasympathetic fibers, which originate from the pelvic splanchnic nerves, as well as sympathetic fibers, nearly all of which are derived from the superior and inferior hypogastric plexuses and nerves.

The parasympathetic nervous system is responsible for transmitting bladder sensations related to distension or irritation (caused by an infection or a stone). Sacral nerves carry these to S2-4. From here, feeling passes through the spinal cord’s dorsal columns and into the brain.

Clinical significance

Inflammation and infection

Bladder infection or inflammation can be referred to as what is cystitis. Urinary retention is habitual in guys in early life and elderly men have a growing prostate. Other indicators of risk include the presence of extramarital structures in the urinary tract, such as urinary catheters, neurologic troubles that make passing urination difficult, and other causes of obstructions or constriction, such as prostate cancer or vesicoureteral reflux. Bladder infections can result in lower abdominal pain (above the pubic symphysis, or “suprapubic” pain), especially before and following urinating, as well as a need to urinate often and unexpectedly (urinary urgency).

Incontinence and retention

Urinating a lot is frequently caused by small bladder capacity, irritation, insufficient bladder emptying, or excessive urine production. A larger prostate causes men to urinate more frequently. Drinking more than eight times a day is one symptom that a person has an overactive bladder. Though both urine frequency and volumes have been proven to have a circadian rhythm, meaning day and night cycles it is not known how these are impacted in the overactive bladder.

Bladder disorders include the following:

- bladder exstrophy

- paruresis

- trigonitis

- underactive bladder

FAQs

The substance storage and removal are the bladder’s two primary purposes. The bladder helps people stay unconscious by dealing with and avoiding the need to urinate. An adult has a 400–500 ml bladder capacity and needs to urinate four to eight times a day.

You may need to limit or stay away from acidic foods, caffeine, and alcohol. Breaking down liquids, getting in shape, or doing more exercise can all help to improve that problem.

This kind of bladder cancer seldom results in death. Muscle-invasive bladder cancer occurs when malignant cells invade the bladder’s surrounding muscles to get to its lining.

Is feasible to make it without a bladder? It is possible to stay alive without a bladder, but you will require a new container to store the urine your kidneys produce. You may need some time adjusting to your new breaking elegance if a surgeon extracts your bladder whole.

References

- Marvalee H. Wake (15 September 1992). Hyman’s Comparative Vertebrate Anatomy. University of Chicago Press. p. 583. ISBN 978-0-226-87013-7. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ^ Brading, Alison F. (January 1999). “The physiology of the mammalian urinary outflow tract”. Experimental Physiology. 84 (1): 215–221. doi:10.1111/j.1469-445X.1999.tb00084.x. ISSN 0958-0670.

- ^ Boron, Walter F.; Boulpaep, Emile L. (2016). Medical Physiology. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 738. ISBN 9781455733286. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ Walker-Smith, John; Murch, Simon (1999). Cardozo, Linda (ed.). Diseases of the Small Intestine in Childhood (4 ed.). CRC Press. p. 16. ISBN 9781901865059. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ Jump up to a b c Netter, Frank H. (2014). Atlas of Human Anatomy Including Student Consult Interactive Ancillaries and Guides (6th ed.). Philadelphia, Penn.: W B Saunders Co. pp. 346–8. ISBN 978-14557-0418-7.

- ^ “SEER Training: Urinary Bladder”. training.seer.cancer.gov.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Viana R, Batourina E, Huang H, Dressler GR, Kobayashi A, Behringer RR, Shapiro E, Hensle T, Lambert S, Mendelsohn C (October 2007). “The development of the bladder trigone, the center of the anti-reflux mechanism”. Development. 134 (20): 3763–9. doi:10.1242/dev.011270. PMID 17881488.

- ^ Jump up to a b c d e f Young, Barbara; O’Dowd, Geraldine; Woodford, Phillip (2013). “Urinary system”. Wheater’s functional histology: a text and color atlas (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 315–7. ISBN 9780702047473.